By Sourabh Gupta

Future Warfare in the Asia Pacific: Chinese Anti Access/Area Denial, US Air Sea Battle, and Command of the Commons in East Asia

Stephen Biddle and Ivan Oelrich

International Security, 41:1, Summer 2016

Biddle and Oelrich address the idea that the US’ “command of the commons” (worldwide, unchallenged, freedom of movement) is coming to an end in the Western Pacific as China gains more effective anti-access area denial (A2/AD) capabilities. They begin by noting that China’s A2/AD capabilities are not a direct threat today, but could be in the future. In this context they evaluate the long-term utility of the US’s AirSea Battle concept and prospects for Chinese hegemony in the Western Pacific, expressing skepticism about the prospects for each.

US-China Relations: Friction and Cooperation Advance Simultaneously

Bonnie Glaser

CSIS, September 2016

Glaser surveys key moments in US-China relations from mid-2016. During the eighth US-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue, both the US and China acknowledged “positive developments in the bilateral relationship,” agreeing to deepen cooperation in areas like nuclear non-proliferation, promotion of open trade and investment, communications, and anti-corruption. However, both countries were still divided on issues like the South China Sea, sanctions on Pyongyang, human rights, and excess capacity. Despite concerns, both parties agreed to push forward negotiations on the Bilateral Investment Treaty and establish mechanisms for communication during their US-China Cybercrime and Related Issues High-Level Joint Dialogue. In July, the US responded cautiously to the UNCLOS tribunal’s ruling on the South China Sea, but emphasized its respect for freedom of sailing and hoped that all parties would “exercise restraint.” China expressed concerns over the deployment of THAAD during Susan Rice’s visit to Beijing, but military/military ties “maintained an active pace” with Adm. Richardson’s visit to China and Chinese participation in the RIMPAC military drills.

A Sharper Choice on North Korea: Engaging China for a Stable Northeast Asia

Mike Mullen, Sam Nunn, and Adam Mount

Council on Foreign Relations, September 2016

This task force report suggests that it is necessary for the next administration to solidify its relationship with China so as to effectively combat North Korea’s nuclear threat. First, the US should present DPRK with an ultimatum: failure to comply with UN resolutions will lead to severe and escalating consequences and at the same time, the US and China should open an official dialogue on the future of the Korean Peninsula. Second, the US should expand South Korea and Japan’s deterrence capabilities. Third, the US and its allies should also offer restructured negotiations that provide genuine incentives for DPRK to participate in talks with increasing pressure via sanctions. To encourage China’s participation, the US must convince China that Korean unification will not damage its interests and schedule regular five-party talks (China, Japan, Russia, South Korea and the US) to ensure integrated regional stability.

Can the US-Philippine Alliance Endure Duterte?

Patrick Cronin and Anthony Woon Cho

Center for New American Security, September 14, 2016

Filipino President Duterte has surprised many with his apparent recklessness and open antagonism toward the US, but Cronin and Cho argue that Duterte’s pursuit of an independent foreign policy is just wishful thinking. Duterte’s approach has already damaged the US-Philippine alliance, which was viewed by Manila (and is still viewed by most outside of the President’s office) as the Philippine’s most important bilateral relationship. According to the authors, the decades-long, mutually beneficial US-Philippine alliance is still strong, but how long it will last depends on whether Duterte is willing to reverse his current approach.

The Crucial South China Sea Ruling No One Is Talking About

Lyle J Morris

RAND, September 16, 2016

Morris notes three reasons why the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s (PCA) ruling on the South China Sea ruling was so important. First, the ruling decided that China’s actions were not defensive measures against the Philippines’ maritime law enforcement (MLE) actions, but instead were a direct violation of the Convention on International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (Colregs). Second, the Court’s findings on the Colregs issue helped to interpret wider obligations associated with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Seas (UNCLOS), which clarifies important thresholds of MLE violations. Finally, the PCA’s decision emphasized the need for the rule of law to dictate navigation issues.

Chinese Spending Can Help Create Jobs in the US

Henry Paulson

ChinaFile, September 19, 2016

While many Americans blame trade and outsourcing for job losses, Paulson views trade as a stimulus for new jobs. The trade pattern between the two countries is changing as China now sends more direct investment than it receives The inbound flow of Chinese capital will create more local jobs across the US by funding small businesses, start-ups, and various industries. Diminishing opportunities in domestic markets, demand for global expansion, and transition toward less capital-intensive industries incentivize Chinese investors to invest in developed overseas markets including the United States. Americans should benefit from this dynamic, so long as Chinese investors follow the rules and regulations.

The Coming Confrontation with North Korea

Richard Haas

Council of Foreign Relations, September 20, 2016

Haas contends that if North Korea were left unrestrained, the US alliance system in Asia would collapse, giving Japan and South Korea an incentive to develop their own nuclear weapons. Haas points out two options the US can take to prevent such cases from happening—negotiation and sanctions—but neither seems to work under current circumstances. As a result, the US may respond in three ways: do nothing; destroy Pyongyang’s nuclear facilities; or overthrow the regime with the use of force. While all three options will certainly involve military conflict, Haas argues that the US may want to seek more diplomatic support from China, regarding what would be a “fateful decision” for America’s next president.

PacNet #73: Why ASEAN is here to Stay and What That Means for the US

Satu Limaye

CSIS Pacific Forum, September 21, 2016

Limaye argues that it is not a surprise that ASEAN countries failed to come up with unified actions regarding the South China Sea given its fundamental shortcomings. ASEAN as a government-led organization faces challenges in four aspects: ethnic issues within each country, little interest to participate, fewer commitments from key members, and new geopolitical realities. While ASEAN “may be becoming more of an ‘arena’ than a regulator,” ASEAN is still irreplaceable as a focal point for regional issues and extra-regional cooperation.

How to Spark a War in Asia

Ted Galen Carpenter

The National Interest, September 24, 2016

If a great power is unable to stop its allies from “creating unwanted security crises,” it may find itself in a dangerous situation. Carpenter observes some early signs of this challenge in the Asia Pacific as China and the US find it difficult to influence their allies’ agendas: China’s de facto ally North Korea continues to build up its nuclear arsenal in spite of China’s warnings and sanctions, while two long-standing US allies in the region—Taiwan and the Philippines—seem to be diverging from Washington under new leadership. For both Chinese and American policymakers, it is time to reassess their security promises to these allies before the coming of a major security crisis.

The US-China Cyber Espionage Deal One Year Later

Adam Segal

Council on Foreign Relations, September 28, 2016

Since the US and China pledged to refrain from cyber-enabled theft of intellectual property one year ago, reports suggest that the overall level of Chinese-backed hacking has decreased. However, Segal argues that Chinese hacking may simply have become more sophisticated, more focused, and more difficult to trace. Segal concludes that, while the US and China have clear shared interests in cybersecurity, it is difficult to translate these interests to concrete policy due to the nature of cyber espionage.

The US, China, and the 2016 Vote

Asia Society, September 15, 2016

In a wide-ranging discussion on the state of US-China relations, former US Ambassador to China Winston Lord contended that the relationship has entered a new phase he called “controlled enmity.” He held that the US should treat China as an equal partner despite the fact that what he views as “increasing aggression abroad” have revealed a lack of trust in the Chinese leadership towards the US. He suggested that the best way to improve US-China relations is “to be aware of the [reality] we are in.” Orville Schell observed that is difficult to explain China to Americans who don’t see the differences between a Chinese political system that they are suspicious of and the vibrant, dynamic daily life of the Chinese people. For the next president, neither speakers made positive predictions for a Trump presidency. Lord thought Clinton’s policy will be “a little firmer,” but will be “something the Chinese can predict and get along with.”

How a Turbulent China is Managing a Nuclear North Korea

Center for Security Studies, Georgetown University, September 22, 2016

Gordon Chang delivered a talk highlighting four crucial changes in China and North Korea (DPRK) that will affect their relationship with one another and how China manages the DPRK’s nuclear program. First, Kim Jung Un’s waning domestic support indicates the incompatibility between building up nuclear arsenals and achieving economic development. Second, Chinese officials are reluctant to continue supporting the DPRK. Third, DPRK’s nuclear program is spurring an international coalition against its regime, which could result in the collapse of Kim’s control and further DPRK reliance on China. Finally, China itself is undergoing a turbulent period, with changes in its military, society and economy. Against the backdrop of the rising instability in East Asia, these four changes could allow “anything to happen” on the Korean peninsula. However, Chang concluded that it was “unlikely” that China would withdraw its support for North Korea, so any actions the US and its allies take against the DPRK should carefully consider China’s response.

The Modern Origins of China’s South China Sea Claim

CSIS, September 22, 2016

British geographer Bill Hayton discussed the history of China’s South China Sea claims, including the origins of the nine-dash-line. He argued that Chinese South China Sea claims are modern, and were first developed in the 20th Century in response to domestic political crises. He argued that the importance of the region to China is similarly a result of these circumstances and that popular interest in the sovereignty issues has been deliberately cultivated by Beijing.

By Sourabh Gupta

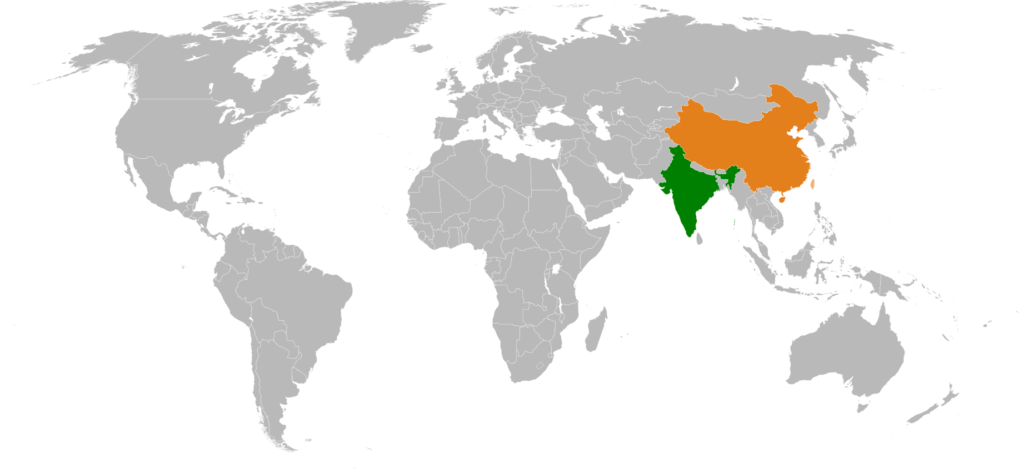

On 4 February 2016, China and India held the first round of their “Maritime Affairs Dialogue” in New Delhi. As these great civilizational spaces, and modern-day nation states, open a new chapter in bilateral maritime relations, it is instructive to distil the lessons of an earlier age.

First, Asia was one, united by bonds of commerce, culture and civility; Second, the spread of Buddhism from South Asia along the ‘belt’ and ‘road’ wove a common world of religious-cultural ambiance and sensibility that signified both integration and cosmopolitanism; Third, China and India had once been the great originators of globalization. The political and economic architecture of such contact was never closed off or exclusive but rather was open and inclusive; Fourth, Asia’s seas were genuinely res communis (common heritage of mankind) that belonged to all and was denied to none; these waterways were not an arena of geopolitical contestation. Further, each sovereign entertained a vested interest in preserving the freedom of these waterways and which no sovereign sought to dominate.

The key features and wisdom of the old must inform the guiding principles that shape the modern characteristics of the new in Asia’s 21st century maritime order.

First, China and India must firmly tether their maritime interactions to the Panchseel/Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence – i.e., to the principle of sovereignty and mutual respect for core/primary interests; to the concept of peace and opposition to war, war-mongering, aggression and threat of use of force; to the promotion of cooperative and collaborative (win-win) patterns of cooperation that eschew adversarial zero-sum contestation and exclusive alliances; and to the concept of justice, including the fair application of international law and principles of democracy in bilateral and regional engagements. The aim of the Five Principles is to embed China-India interests and aspirations in the maritime sphere within a cooperative, comprehensive and sustainable architecture that realizes an Asian community of common destiny.

Second, China and India must restore Asia’s seas to their former purpose as win-win economic passageways rather than arenas of zero-sum contestation. In February 2014, at the 17th round of Special Representative talks in New Delhi, China formally invited India to join its ambitious Maritime Silk Route (MSR) project. The Narendra Modi government should actively seek out synergies with its “Sagar Mala” port development and transport infrastructure project and exert its influence to craft the contours of MSR’s South Asia blueprint to make it complementary to New Delhi’s own neighborhood policy. Further, it must not pass up the opportunity to build matching cross-border connectivity links that bind India to its periphery and integrate the latter via the ‘belt’ and the ‘road’ to global networks. By recreating the famous land and sea routes along which commerce and cosmopolitanism once traversed, ‘One Belt, One Road’ will also re-awaken India in no small measure to its own golden age of cross-border contact.

Third, China and India must continue to jointly nudge the thrust of oceanic law and global oceans governance towards sustainable economic, developmental and conservation-related ends and to the relative disfavor of military and other non-peaceful uses of the sea. Both countries hold similar or identical views on foreign user state rights, particularly on military navigation and related activities, within their exclusive maritime zones – be it innocent passage rights through their territorial seas or active intelligence gathering as well as hydrographic surveys within their EEZ.

China and India should initiate a dedicated bilateral dialogue on the development of the UNCLOS (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, 1982) regime, with a view to harmonizing opinions to push the perimeter of such ‘threat-based’ activities further away from their coastlines. Taking the long perspective, the two countries along with their Asian partners should also develop soft law that catalogues permissible and non-permissible threat-based activities in a coastal state’s EEZs and thereafter seek to elevate that norm, by way of state practice over time, into the body of local customary law.

China and India should economically complement this UNCLOS policy dialogue with an agreement to share technological knowledge on seabed research and mining for polymetallic nodules. A joint application to the International Seabed Authority (ISA) to secure exclusive mining rights in both the Indian Ocean and the Western Pacific could also be considered.

Fourth, China and India must seek out areas of strategic congruence in their Asia-Pacific-wide maritime engagements, while grappling with – and managing – their differences with frankness and sincerity. For the most part, both countries fundamentally share common interests in maritime Asia, yet would rather pursue these interests – and frame strategies – separately. Both China and India share an interest in keeping their overlapping sea lines of communication open to free navigation, yet both seek to exercise control – and leverage via the veiled threat of interdiction – over the chokepoints through which these sea lanes pass.

Both China and India retain an interest in securing sea-borne access to ensure the economic viability of their landlocked, underdeveloped regions (Yunnan; Northeast India), yet both would prefer to design connectivity initiatives that run at odds with their counterpart’s. Since 2014, both China’s and India’s navies have begun to bump-up more frequently in the proximity of each other’s naval bastions (in the East China Sea, South China Sea and Eastern Indian Ocean/Bay of Bengal), yet neither has initiated a conversation on reassuring its counterpart of its intentions.

As a first step, both China and India must commit to respecting each other’s ‘core’ or ‘primary’ interests in their respective backyards. To the extent that either country possesses a vital interest – be it navigational, oil and gas, or access – in the other’s ‘core’ or primary’ geographical area of interest, the former should seek to transparently communicate its purposes and intentions.

Conversely, both countries must respect each other’s maritime engagements with third parties in Asia’s seas – so long as these engagements do not impinge on the other’s ‘core’ or ‘primary’ interests. To the extent that both countries seek to sanitize and secure their respective naval bastions (to ensure the future integrity of their second-strike deterrence capability), both countries bear an obligation to defer to their counterpart and keep their surface fleets at some distance from these locations.

To the extent that both countries seek to exercise control—and leverage—over the chokepoints through which the critical sea lanes of Asia pass, both countries would rather be better-off exploring a broader bargain that resists the temptation to challenge each other’s growing power, influence and authority east and west, respectively, of the island of Sumatra.

Parenthetically, it bears noting that no sustained and economically significant campaign to interdict the maritime trade of a major power has been mounted since the 18th century – except in the case of a general war. A veiled threat of choke-point interdiction, then, that is only as good as its non-activation makes for good theater but reflects poor policy.

Finally, China and India must functionally elevate their operational interactions across the length and breadth of Asia’s seas. Much like the Wako pirate raids along the eastern seaboard had invited the Yongle Emperor’s initial turn to the sea, so also the Convoy Coordination Working Group featuring China and India among others, as part of the anti-piracy mission in the Gulf of Aden, has served as a useful initial basis for bridge-building and cooperation.

Both countries must utilize this precedent to deepen navy-to-navy engagement across a range of non-traditional security missions, including notably but not limited to humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HA/DR) activities. Ideally, such China-India HA/DR cooperation should hew to the spirit of openness and be situated, in deference to ASEAN centrality, within the emerging practice of Asian security multilateralism.

Over time, China and India should also aspire to operationally devise a multilateral, cooperative sea-lane security regime for Asia. Both countries should pick-up the exploratory ideational threads of recent years in this regard and formulate a framework for a joint or cooperative sea-lane command which, again, should be housed within the emerging practice of Asian security multilateralism. The positive-sum gains from such collaborative, operational action would be a tangible expression of the willingness of Asia’s major and rising powers to share the burdens and benefits of global and regional stakeholder-ship, while restoring Asia’s seas at the same time to the res communis that it had once been which belonged to all and was denied to none. Cooperative sea-lane security will also draw the curtains down for good on that remnant of the Vasco da Gama interlude in Asia’s seas, which had deliberately introduced state-controlled (threat of) violence along strategic passageways to secure politico-economic ends.

China and India stand on the cusp of a new and promising chapter in bilateral relations. The many lessons learnt during the course of interactions to stabilize their disputed land boundary offer useful pointers as they chart out a rules-of-the-road framework to guide their interactions at sea. Both countries must resolve to address each other’s legitimate interests with a sense of sincerity. Both countries should prioritize peace and tranquility during the course of maritime interactions that impinge on each other’s ‘core’ or ‘primary’ interests. As a measure of mutual trust is devolved, both countries should enumerate – and capture by way of a framework agreement – a lucid set of principles-based parameters of bilateral naval cooperation that obey the injunctions of the Five Principles, is consistent with the open, inclusive, and transparent security architecture of Asia, and fortifies the on-going developmental orientation of global sea law.

Keeping Asia’s seas open to free passage and closed to major power contestation must be the foundation for China-India cooperation at sea over the near and long-term. Together, China and India can re-create a new regional and international maritime order that is inspired by the virtues of the old while embodying the promise of the new Asian Century.

Sourabh Gupta is a Senior Fellow at ICAS. This commentary first appeared on China-India Dialogue.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2024 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.