EVENT SUMMARY

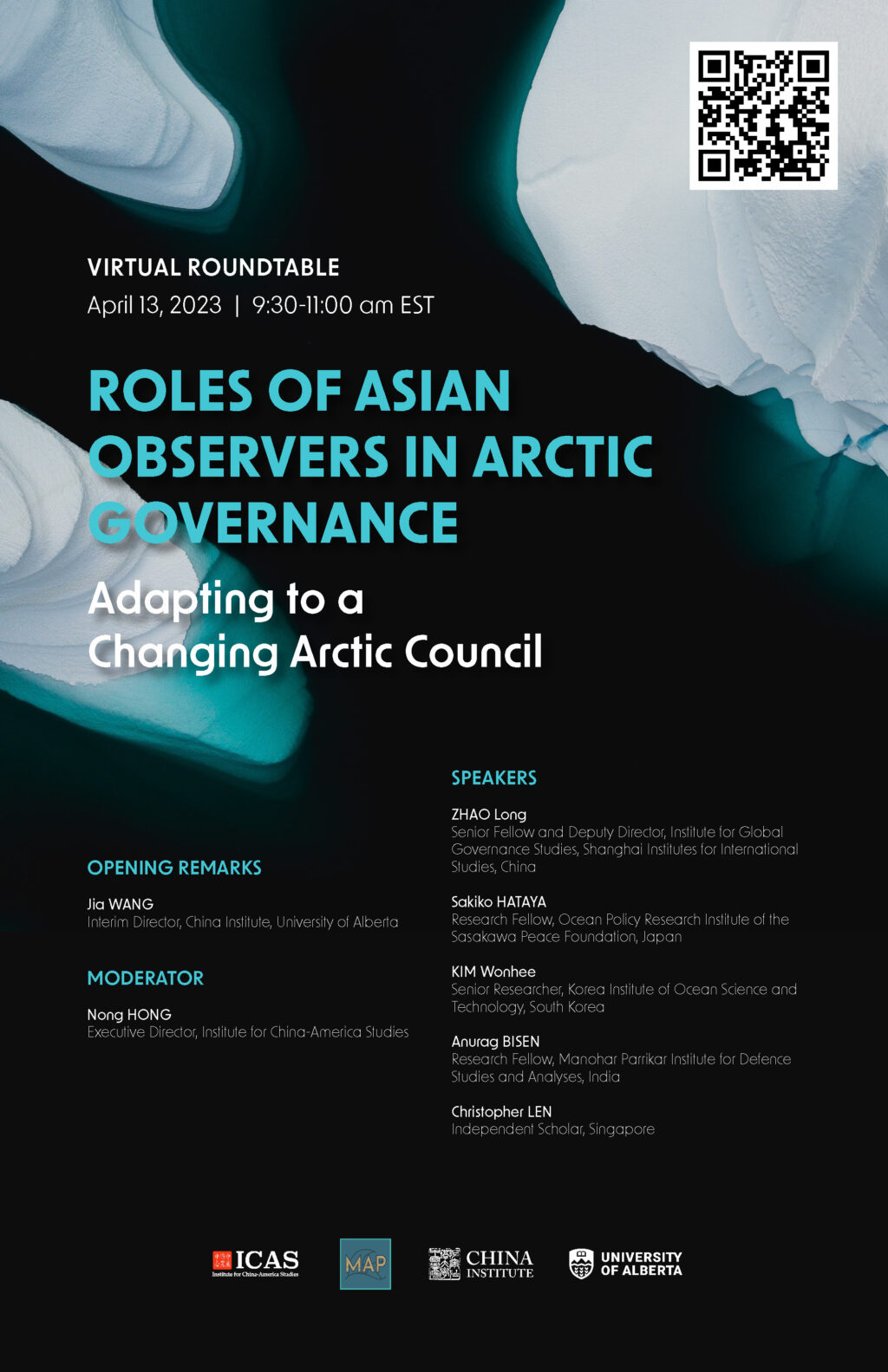

On April 13, 2023, the ICAS Maritime Affairs Program (MAP) and the China Institute at the University of Alberta (CIUA) co-hosted an online roundtable discussion on the “Roles of Asian Observers in Arctic Governance: Adapting to a Changing Arctic Council.” This event brought together scholars from the five Asian observer states of the Arctic Council—China, Japan, South Korea, India and Singapore—to exchange their views on the modern state of Arctic governance. The session was moderated by Nong HONG, Executive Director, Institute for China-America Studies.

Jia WANG, Interim Director, China Institute, University of Alberta, opened the discussion by highlighting how climate change is increasing access to potential shipping lanes and resources in the Arctic. However, Arctic governance through the Arctic Council, a forum historically characterized by deep multilateral cooperation, has become mired by unprecedented tensions and concerns resulting from the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Throughout the last decade, the growth of international attention on Arctic environmental, economic and security issues has brought distant countries to the discussion table as observer states on the Arctic Council. Wang invited the audience to carefully consider the gathered scholars’ opinions on how to rehabilitate Arctic cooperation, however distant from the poles these countries may be.

ZHAO Long, Senior Fellow and Deputy Director, Institute for Global Governance Studies, Shanghai Institutes for International Studies, began by pointing out that this year is the tenth anniversary of China becoming an observer state in the Arctic Council. Dr. Zhao suggested that over the past decade, China has evolved from a “so-called newcomer” into an avid leader and contributor to Arctic affairs that has delivered solid outcomes. Dr. Zhao pointed to the “China’s Arctic Policy” white paper issued in 2018 as the foundation guiding China’s Arctic engagement. The white paper underscores cooperation as the first principle of China’s regional approach with a policy emphasis on promoting mutual understanding and multilateral governance. Dr. Zhao then talked about the three pillars of China’s Arctic policy: science-based participation, sustainable use of the Arctic, and goal-based governance. China is and will continue to be an active participant in the Arctic Council and other multilateral dialogues in the region. However, he argued that geopolitical tensions, which led to the suspension of Arctic Council meetings, have turned China into a “victim in today’s Arctic dilemma” and hindered Beijing’s potential to engage with the region in its preferred manner. Dr. Zhao concluded by confirming “the state of the Arctic Council is at a decisive crossroads…[and], whether it is dead or just stagnated, this very much matters to all of us.”

Sakiko HATAYA, Research Fellow, Ocean Policy Research Institute of the Sasakawa Peace Foundation, introduced Japan’s Arctic policy, which she argued is focused on research, international cooperation, and sustainability. She suggested that, although Tokyo is willing to continue scientific cooperation with other countries in the region, the war between Russia and Ukraine and the subsequent suspension of the Arctic Council’s activities is making it difficult to bring about new engagements. In terms of regional conduct, Ms. Hataya stressed that laws and regulations within the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) framework must be observed in the Arctic, and that the rule of law should be respected. Finally, Ms. Hataya expressed hopes for dialogue through the Arctic Council to be restarted soon because “under the current situation it’s honestly difficult for Japan to contribute.”

KIM Wonhee, Senior Researcher, Korea Institute of Ocean Science and Technology, presented on South Korea’s Arctic policy. Dr. Kim characterized South Korea as a “newcomer” to the Arctic with significant domestic skepticism surrounding the potential for its engagement in the region. Nevertheless, investment in Arctic governance and scientific research gained significant political momentum in Seoul over the last decade, culminating in the first ‘Polar Policy Masterplan’ for Years 2023-2027 which affirmed and integrated South Korea’s approach to the two poles. Dr. Kim then described South Korea’s achievements and flaws so far, arguing that the nation has had “successful achievements in science and research, but is still far behind on industrial issues” such as shipping rules and fishery issues. Lastly, Dr. Kim lamented the suspension of the Arctic Council, as Seoul sees no alternative forum for Arctic dialogue. He stated that it will be very difficult for South Korea to engage further in the region if the conflict in Ukraine continues to leave the body frozen.

Anurag BISEN, Research Fellow, Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, began his remarks by referencing India’s storied presence in the Arctic; from its initial foray into the region with the 1920 Svalbard Treaty, to its modern Svalbard’s Himadri station that has been used by up to 400 scientists since the station was first set up in 2008. The main objectives of India’s contemporary Arctic policy are increasing the intensity of regional engagement, harmonizing polar research with that of the ‘third pole’ in the Himalayas, increasing the volume of regional scientific research, and improving domestic understanding of the Arctic. Capt. Bisen centered his remarks around the potential roles that Asian observer states could play in the Arctic Council amid its uncertain future. “One possible scenario,” he suggested, “is the Arctic Council splitting right in the middle…[with] Russia likely to gravitate towards India and China.” Bisen emphasized India’s strong relationships with both the U.S. and Russia, as well as its connections with other Arctic states, and noted the complex set of opportunities and challenges that the Arctic presents for India. He argued that India should remain engaged in the region, stating “observer states could use this opportunity to seek a more inclusive and equitable [Arctic] Council.” Additionally, Capt. Bisen expressed optimism for India and China’s collaboration in the Arctic, despite existing hurdles, and highlighted the potential contributions of India’s G20 presidency to breaking the ice congealed over the Arctic Council.

Christopher LEN, an independent scholar based in Singapore, previously working as the Senior Research Fellow and Head of Publications at the Energy Studies Institute, National University of Singapore, emphasized Singapore’s interest in the Arctic region despite its equatorial location and lack of polar research experience. Dr. Len outlined three primary motivations: maritime law issues, business opportunities, and climate change. He explained, “as a major maritime hub, Singapore is keen to engage in the law of the sea issues and there are a lot of relevant issues in the Arctic.” Furthermore, Dr. Len highlighted Singapore’s vulnerability to climate change, noting that “Singapore is especially vulnerable to sea level rise and thus keeps a keen eye on climate change in the Arctic and how it might affect the environment in Singapore.” Dr. Len also highlighted the significance of international cooperation and knowledge sharing. He mentioned that the Arctic Council serves Singapore as a unique vector for political engagement that has helped foster new layers of political engagement with other member states. Lastly, Dr. Len emphasized the importance of raising global awareness of the Arctic region and promoting understanding of its connection to the rest of the world.

The event concluded with an open panel discussion moderated by Dr. Nong Hong, and welcoming audience questions. In response to a question about changes in regional shipping following the Ukraine crisis, Ms. Hataya noted that Japanese companies are “becoming even more cautious” on the issue, the future of which “is becoming more difficult to predict,” though they will not fully withdraw from the Arctic. The speakers had varying opinions on predictions regarding how the upcoming chairmanship transfer to Norway will impact the Arctic Council operation status. All five participants agreed, to differing degrees, that any attempt at collective Arctic governance would not succeed without the participation of Russia. The panelists acknowledged that, despite Russia’s pariah status on the international stage amid Ukraine tensions, it remains the largest and most influential Arctic power. Dr. Kim and Ms. Hataya also admitted that smaller-scale efforts in the Arctic—such as China-South Korea-Japan trilateral initiatives—have largely come up short and do not present a viable alternative to the Arctic Council. Dr. Zhao suggested that a more broad-based ‘Asian Forum’ in the Arctic could be a workable middle ground between the Asian trilateral approach and the contentious Arctic Council. Appeals to exclude Russia from multilateral Arctic cooperation may retain some momentum in the short-term, such as during Norway’s upcoming rotating chairmanship of the Arctic Council, but the panelists agreed that this should not become the ‘new normal’ if the Ukraine war evolves towards a ceasefire.

Some disagreement surfaced as the panelists debated what a rehabilitated Arctic Council could look like. Dr. Zhao expressed hopes for a return to normalcy with Asian observer states taking a leading role in engaging Russia and pushing past tensions by engagement in sustainable development and scientific cooperation. Dr. Len agreed, adding “engaging with indigenous groups” and “information sharing” to this list of “low-hanging fruit.” Capt. Bisen, however, dismissed the idea that Arctic governance could return to its previous state, as the Arctic Council’s stagnation in the wake of the Ukraine crisis and ultimate suspension of its activities has dealt an irreversible blow to its credibility—the body is less workable now, he argued, than during the height of the Cold War. Nevertheless, the panelists agreed that Asian observer states, without the security baggage of Russia’s Nordic neighbors, have an opportunity to play constructive roles in reforging Arctic cooperation by engaging Russia bilaterally in policy areas (such as scientific research) that are less likely to be securitized. While the panelists predicted that multilateral fora for Arctic cooperation may never be as comprehensive as they were before, they agreed that such engagement has the potential to build Arctic governance back into a source of regional stewardship, opportunity and discovery.

– OPENING REMARKS –

Jia WANG

Interim Director, China Institute, University of Alberta

Jia Wang is currently the Interim Director of the China Institute at the University of Alberta, where she manages research, programs, and government and media relations since 2011. Jia has over 15 years of direct management experience focusing on the economic and political dimensions of contemporary China and Canada-China relations in various capacities. At the China Institute, in addition to overseeing the operations, she leads policy research initiatives examining Canada’s diplomatic, trade, investment and energy linkages with China. Jia also provides strategic and policy advice on China to University senior leaders as well as executives at public and private sector organizations. She is a frequent media commentator, speaker and moderator at community, national and international events.

– MODERATOR –

Nong HONG

Executive Director, Institute for China-America Studies

Nong HONG holds a PhD of interdisciplinary study of international law and international relations from the University of Alberta, Canada and held a Postdoctoral Fellowship in the University’s China Institute. She was ITLOS-Nippon Fellow for International Dispute Settlement and Visiting Fellow at Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources and Security, the Center of Oceans Law and Policy, University of Virginia, and at the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law. She is concurrently a research fellow with China Institute, University of Alberta, Canada, and the National Institute for South China Sea Studies. She is also a China Forum expert.

– SPEAKERS –

ZHAO Long

Senior Fellow and Deputy Director, Institute for Global Governance Studies, Shanghai Institutes for International Studies, China

ZHAO Long is a senior fellow and the deputy director of the Institute for Global Governance Studies at Shanghai Institutes for International Studies, the Council Member of China National Association for International Studies. ZHAO graduated from the law faculty at Moscow State University of Russia, receiving a BSc in jurisprudence and a MA in international law, and received his Ph.D. in law from East China Normal University. His research focuses on Global governance, Russian and Central Asian studies, and Arctic affairs, published academic articles and commentaries widely. ZHAO was a visiting scholar of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington D.C and the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP) in Berlin. From 2015 to 2016, ZHAO was on secondment to the Department of Treaty and Law at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China.

Sakiko HATAYA

Research Fellow, Ocean Policy Research Institute of the Sasakawa Peace Foundation, Japan

Sakiko HATAYA is Research Fellow at the Ocean Policy Research Institute of the Sasakawa Peace Foundation. Her research is centered on the Law of International Organization, and Polar Law. She has studied functions of the Arctic Council.

KIM Wonhee

Senior Researcher, Korea Institute of Ocean Science and Technology, South Korea

KIM Wonhee is a Senior Researcher of the Korea Institute of Ocean Science and Technology (KIOST). Prior to joining the KIOST, he was a senior researcher of Korea Maritime Institute and a Secretary in Chief of the Korean Society of International Law. He also has taught public international law and judicial settlement of international disputes at Konkuk University, Ewha Womans University and Korea National Open University. His research interests include the law of the sea, territorial and boundary dispute, maritime security, and the law and practice of international courts and tribunals. Recent publications include “Re-conceptualization of the Critical Date in Territorial Disputes in the Light of the Law of Evidence before the International Courts and Tribunals” (2020), “The Limits and Roles of International Law in the Disputes between Ukraine and Russia over Crimean Peninsular” (2021), and “Challenges to the UNCLOS Regime by Sea-level Rise and Its Implications for the Ocean Law and Policy” (2022).

Anurag BISEN

Research Fellow, Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, India

Captain Anurag BISEN is a serving Indian Navy officer with almost 35 years of service. A submariner, he has commanded a Kilo Class missile submarine. He joined the MP-IDSA after an extended tenure in the National Security Council Secretariat, where he worked on maritime issues, including maritime boundary and legal issues, the Indo-Pacific, the Indian Ocean region, maritime and coastal security, and Polar issues. He was instrumental in drafting and winning approval of India’s Arctic Policy, released in March 2022. He is a graduate of the Defence Services Staff College and holds a bachelor’s degree in Law, a master’s in Telecom, and a Russian language diploma from Arkhangelsk State University, Russia.

Christopher LEN

Independent Scholar, Singapore

Christopher LEN is an independent scholar based in Singapore. He was a Senior Research Fellow and Head of Publications at the Energy Studies Institute, National University of Singapore from 2012 to 2022. His research focuses on Asian energy and maritime security issues, regional infrastructure connectivity, Chinese foreign policy, as well as the growing political and economic linkages between the various Asian sub-regions. He also has an interest in the Arctic region, focusing on energy policy-related issues in the Arctic which are also of relevance to the wider world — from the governance of sustainable energy transition, to energy access in remote locations, maritime infrastructures and shipping and issues related to innovation, resilience and capacity-building. Christopher obtained his PhD from the Centre for Energy, Petroleum and Mineral Law and Policy (CEPMLP) at the University of Dundee in Scotland where he was awarded the Dean’s Medal for Research. He also has degrees from the University of Edinburgh, Scotland and Uppsala University, Sweden.

EVENT TIME ZONES

Local Event Time: 9:30-11:00am EDT (GMT-4)

- Alberta, Canada: 7:30am-9:00am (GMT-6)

- New Delhi, India: 7:00pm-8:30pm (GMT+5:30)

- Singapore: 9:30pm-11:00pm (GMT+8)

- Shanghai, China: 9:30pm-11:00pm (GMT+8)

- Busan, South Korea: 10:30pm-12:00am (GMT+9)

- Tokyo, Japan: 10:30pm-12:00am (GMT+9)