Cover Image: Flickr/Gage Skidmore (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Research Associate &

Program Officer

The heat of the election forced Joe Biden to project that he could be just as tough on China as Donald Trump. However, there were stark differences between Biden and Trump on how to handle the numerous economic, societal, and security issues pervading the U.S.-China relationship. Biden’s lengthy political career provides a lens as to how he has evolved on China and where his priorities have shifted.

As a Senator from 1972-2008 and member (and later Chair) of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Biden was instrumental in shaping the initial trajectory of the U.S.-China relationship since its normalization in 1979, particularly on trade.

Although Biden frequently co-sponsored or voted on legislation condemning Chinese human rights violations and security concerns, he, like many other Democrats and Republicans at the time, was quick to shift priorities in order to develop and maintain the rapidly growing economic relationship with China.

While Vice President, Biden took the helm of the second Obama Administration’s China portfolio, he worked tirelessly to prop up the United States’ regional economic liberalization goals with strategic partners through the Trans-Pacific Partnership, as well as supported a forward military presence in the Western Pacific to manage China’s increasingly assertive economic and foreign and security policy behavior.

The process of decoupling is likely to continue, albeit differently in some areas, under a Biden Administration, though he will be more amenable to cooperation with China in certain areas, ranging from climate change to the denuclearization of North Korea.

China will likely continue its aggressive pursuit of its interests in the areas of security, technology, and financial services, which the U.S. will feel compelled to respond to. This will likely occur at the cost of the business community, which historically served as the ballast of the U.S.-China relationship.

As perhaps one of the most contentious elections in U.S. history reaches its dramatic conclusion, with Biden as the President-elect, the conversation around the future of U.S.-China relations has intensified. From the turbulent negotiations over the Phase One Trade Deal to a growing push towards economic decoupling, American businesses and the international community have been scrambling to adapt to the ever-evolving U.S.-China relationship, which has been exacerbated even further as a result of the global COVID-19 pandemic. Although some key China policy changes are expected under Biden, their specifics remain unclear, particularly as they would be enacted following Trump’s tumultuous administration.

2020 Democratic Party Presidential candidate and now President-elect, Joe Biden, has a storied political career. He was first elected as a Senator for Delaware in 1972, seven years before the U.S. and the People’s Republic of China normalized diplomatic relations on January 1, 1979. Biden made his first ever trip to China in April of that year to meet with China’s then leader, Deng Xiaoping, as part of the first delegation visit following the normalization of diplomatic relations. As a member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee at that time, he firmly believed that “a rising China is a positive, positive development, not only for China but for America and the world writ large.”

Biden’s China policy can be likened to the Chinese idiom, “打太极”, or “practicing tai chi.” On the one hand, Biden has carefully hidden most of his cards on how he will differ from Trump’s China policy. Yet, on the other hand, Biden’s past and present legislative and policy record shows that he has been very flexible and contradictory in his votes and rhetoric, lacking solid ground on where he stands exactly on economic, societal, and security issues with China. With Biden having won the presidential election, many in the U.S. and abroad are now turning their attention to speculating what U.S.-China relations will look like under a Biden-Harris Administration. Will Biden’s China policy simply be Obama 2.0? Will it be along similar lines of the Trump Administration’s policy of being ‘hard’ on China? Will it be some mixture of the two? Or, perhaps, something else entirely?

Up to now, Joe Biden has far more clearly laid out domestic policy than his foreign policy. However, within the American foreign policy community at large, there is a growing sentiment that one of the greatest mistakes of past China policies among previous Democrat and Republican administrations is that too much focus was placed on attempting to formulate policy that would change China’s development to a more palatable image in the West. More recently, there has been bipartisan support, Biden included, to design a China strategy based on the realities on the ground, rather than around what the U.S. hopes China to become.

The U.S.-China relationship under the Obama Administration has often been characterized as having run under an engagement model that prioritized trade and investment with China over national security. The Trump administration starkly reversed this order of priority, pursuing a policy of decoupling American supply chains and business dealings with China in key sectors. A Biden administration is unlikely to make a full reversal back to the Obama-era prioritizations, but there will likely be some functional changes made. That being said, Biden has pledged to address many of the same trade and economic imbalances that the Trump administration targeted to protect U.S. firms, though this will occur in different ways. Most prominently, we will likely see Biden attempt to:

There is less firepower in the ‘engagement’ camp in the U.S.-China foreign policy community, regardless of left or right leanings. At present, there are debates going on within the Biden team between centrists and progressives as well as globalist and isolationists. It is still too early to form a definitive picture on the outcome and their ramifications on trade and other policies with China. Despite this, however, some form of decoupling is likely to continue under Biden, but in a more nuanced and predictable manner.

This is largely due to the fact that the U.S.-China economic relationship cannot go back to the way it was under the Obama administration. This is not just a result of Trump policy, either. The relations between the countries also fall heavily on what China’s leaders desire in the future – either a revision of the global order, or continued U.S.-China competition with the U.S. still as the global leader. Regardless of who sits in the Oval Office, we are likely to see China continue the aggressive pursuit of its national interests in the areas of security, technology, and financial services that the U.S. will feel compelled to respond to, likely at the cost of the business community. This marriage between economics and security policies is likely to continue under Biden and we are likely to see more actions similar to the recent sanctions on 24 Chinese state-owned companies involved in the militaristic building in the South China Sea.

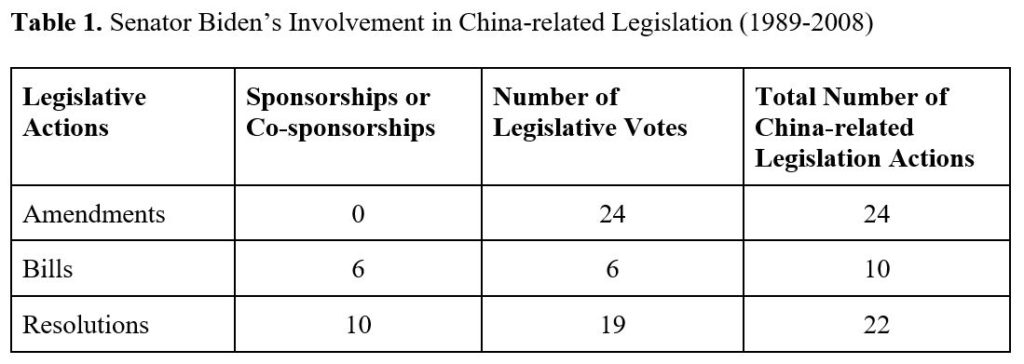

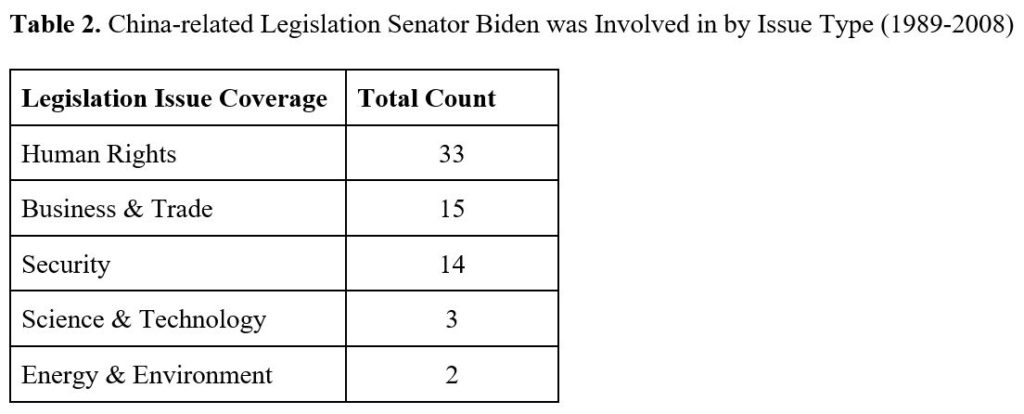

As a member, and eventually Chairman, of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Joe Biden was among many key senators who shaped the initial trajectory of U.S.-China relations during its post-normalization infancy. This section contains an analysis of a database produced by ICAS scholars on then-Senator Joe Biden’s voting record that directly reference or allude to China-specific issues from 1989-2008.[1] 56 of Biden’s sponsorships/co-sponsorships and votes on bills, resolutions, and amendments within the database were categorized into a specific theme, including: human rights, security, business and trade, energy and environment, and technology. In many cases, an issue that was voted on or sponsored by Biden involved more than one of these themes. Importantly, there are key votes that Biden made during his tenure as Senator that contradicts his more recent statements and stances on China.

Through the late-1980s and mid-1990s, Senator Biden most frequently crafted or voted for, as many Democratic and Republican senators did at the time, legislation condemning human rights abuses perpetrated by the government of China. The most prominent example of this was in 1989 when, in the wake of the crackdowns in Tiananmen Square and Tibet, Biden and the other Senate Democrats and Republicans acted largely unanimously in passing legislation to condemn and punish the Chinese government. For instance, Biden joined the House and the Senate to pass H.Con.Res.136, which “condemns the excessive and indiscriminate use of force by the authorities of the People’s Republic of China against its citizens.” Additionally, Biden sought to place economic sanctions by voting for S.Amdt. 271 to S. 1160 (Foreign Relations Authorization Act, Fiscal Year 1990) for these perceived violations of human rights. Biden’s votes also show that he has historically shown concern for China’s military buildup insofar as they concern human rights and aggressive law enforcement concerns when he voted for S. 1160, in which Section 905 places restrictions on arms transfers to China if any equipment is likely to be used to ”enforce martial law in Tibet, to suppress demonstrations by the Tibetan people, or to support violations of the human rights of the Tibetan people.”

Biden’s voting trends continued through the mid-1990s, but reached an inflection point that indicated a shift in priorities beginning in 1997 with his vote against S.Amdt. 890 to S. 955, which would have recommended a revocation of China’s Most Favored Nations trade status. Although Biden continued supporting some legislation that took aim at human rights abuses, these largely focused on rhetoric. When it came to legislation that had measurable, real-world implications for the U.S.-China relationship, Biden began to sing a different tune in his votes. This is largely characterized by his support for the normalization of trade relations and desire to see China join the World Trade Organization, which again was a sentiment held by many Democrats and Republicans at the time as well. However, this conversation in Congress was far from being unanimous as there was much contention about whether to deepen the trade relationship with China.

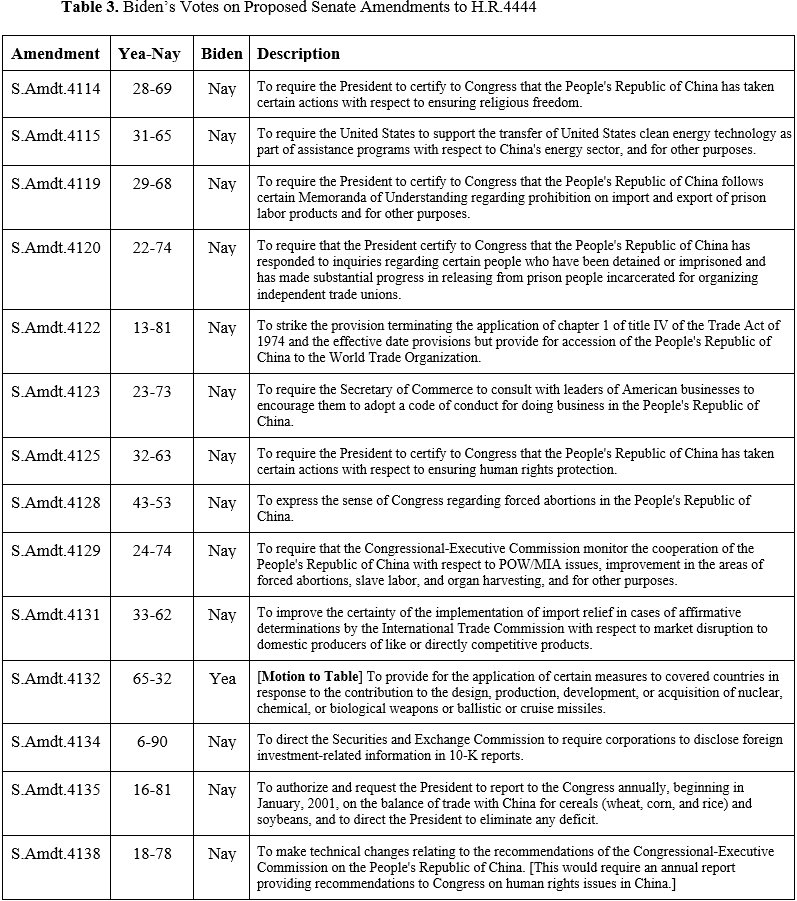

During this time, Biden voted against nearly every proposed amendment to H.R.4444 (the U.S.-China Relations Act of 2000), of which many were closely split down the middle in the Senate. These amendments largely sought to require more stringent and verifiable precursor actions against China in human rights, security, and business/trade issue areas before the U.S. would officially grant normal trade relations. Biden’s single recorded “Yea” vote on proposed amendments to H.R.4444 was actually on a motion to table (effectively killing) S.Amdt.4132, which would have monitored developments and placed appropriate sanctions on China if it was found to be contributing “to the design, production, development, or acquisition of nuclear, chemical, or biological weapons or ballistic or cruise missiles.”

Perhaps, most contradictory to Biden’s ‘tough on China’ rhetoric today on macroeconomic policy are his ‘Nay’ votes on S.Amdts. 4122, 4123, 4131, 4134, and 4135 for H.R.4444. For instance, S.Amdt.4131 attempted to address potential market distorting forces from China that could disrupt the U.S. industrial and agricultural sectors by including product-specific safeguards such as import relief to protect American businesses.

S.Amdt.4123, introduced by Senator Jesse Helms [R-NC] attempted to address the issue of self-censorship and apparent appeasement of the Chinese government, particularly the film industry, in order for American businesses to deepen market access in China. This amendment would have called upon the Secretary of Commerce to consult with American businesses in drafting and adhering to a voluntary Code of Conduct when conducting business in China that would “follow internationally recognized human rights, work against discrimination and forced labor, support the principles of free enterprise and the rights of workers to organize, and discourage mandatory political indoctrination in the workplace.” This issue has once again become part of the national China debate within the last few years, most prominently with the Houston Rockets and new Disney Mulan movie. This vote could be construed as another area where Biden is considered ‘weak’ on China, as he has long been viewed as instrumental in establishing the current status quo in America’s business relationship with China.

S.Amdt.4134 was designed to help protect manufacturing jobs in the United States from moving overseas, to China in particular. Its provisions would have directed the Securities and Exchange Commission to “require corporations to disclose foreign investment-related information in their 10-K reports.” Specifically, corporations would be required to disclose the number of employees employed outside the United States directly, indirectly, through a joint venture, or other. Additionally, corporations would also be required to disclose the annual dollar value of manufacturing exports of goods produced in the United States and of imports of goods produced outside the United States by each reporting entity for each country from which it imported/exported. Although this amendment received very little support on either side of the aisle, it can still be construed that Biden’s ‘nay’ vote contradicts his more recent policies that claim to bring back American jobs (including manufacturing), such as his Made in All of America plan.

The issues addressed within S.Amdt.4135, introduced by Senator Ernest Hollings [D-SC], ought to sound strikingly familiar to some of the prevailing issues addressed within President Trump’s Phase One Trade Deal with China, particularly China’s agricultural purchases pledge. Lowering the balance of trade deficit with China has been a rallying cry for Trump and his supporters as evidence of his hard stance on China. This amendment would have required the President of the United States to provide an annual report to Congress on the agricultural deficit balance with China. Should a significant deficit be found the President would then be authorized and requested to “initiate negotiations to obtain additional commitments from the People’s Republic of China to reduce or eliminate the imbalance.” Biden’s vote against this amendment in 2000, in addition to his mostly false claim during the first presidential debate with Trump that the deficit with China is higher than ever, also contradicts Biden’s rhetoric during his campaign.

In essence, Biden’s tenure as senator as it relates to China policy holds several contradictions to his current rhetoric and stated proposed policies on China. As like many in Congress during the late 1990s and in the 2000s, he promoted the deepening of the trade relationship with China. Although doing so certainly contributed to the positive economic growth for both countries, critics of Biden could easily look at his record as senator and say that he promoted this relationship at the cost of human rights, security, keeping jobs from moving overseas, and preventing the trade deficit from further widening. These policies would continue to varying degrees during Biden’s tenure as Vice President under the Obama Administration as well.

At the outset of the first Obama Administration, Vice President Biden is largely thought to have taken a more domestic policy-focused role. For the first half of the first Obama Administration, Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton, and Secretary of the Treasury, Timothy Geithner, took the helm and oversaw the China portfolio. Clinton and Geithner would hold a number of strategic and economic dialogues with their counterparts in Hu Jintao’s government to discuss evolving issues in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, which was characterized by a recurring theme to those following the development of the bilateral relationship: “the United States came with a long wish list for China on both economic and security issues, while China mostly wants to be left alone to pursue policies that are turning it into an economic superpower.”

From September 2010 through the end of 2012, National Security Advisor Thomas Donilon and National Economic Advisor Lawrence Summers essentially took over heading the direction of Obama’s China policy. However, when it became clear that Hu Jintao would be stepping down from his role as China’s Head of State, and that Xi Jinping was in line to succeed him in late 2012, Donilon is credited with orchestrating a “shift to a strategy of engagement with Biden at the top” that would allow “the US to deal with China’s likely next president from a Vice President to a Vice President/Next President status….” Thus, Biden’s engagement with China as Vice President largely occurred during the second Obama Administration.

This is not to say that Biden had no involvement with China during the first Administration. For instance, Biden met with then Vice-Chairman (of China’s Central Military Commission) Xi Jinping during a China-US Business Dialogue in August 2012 during his first visit to China as Vice President. Biden stressed the importance of cooperation and furthering bilateral ties, yet pressed them on allowing their currency to appreciate, based on market forces as opposed to government controls, relative to the dollar in order to offset trade imbalances. At a Sichuan University speech during this same visit, Biden indicated his alignment with the Chinese notion of ‘win-win cooperation’ between the two countries, stating that “[i]t is in our self-interest that China continue to prosper.” Reportedly, Biden would meet with Xi at least eight times in 2011 and 2012, and come to regard the future leader as “as tough and unsentimental, someone who questioned American power and believed in the superiority of the Communist Party.”

Biden’s interactions with China continued to build steam during the second Obama Administration. On human rights, he was consistently outspoken against Xi’s track record in areas such as press freedom and religious freedom. In response to China preparing to expel nearly two dozen journalists from American news organizations in December 2013, Biden released the American government’s first public warning to Xi Jinping in a formal session. Additionally, prior to Xi Jinping’s accession as General Secretary, Biden says he told the future leader in 2012 that “President Barack Obama would not be able to stay in power if he did not speak of [human rights]. So look at it as a political imperative.” Yet, many would later argue that the Obama Administration soft-pedaled its criticism of Xi’s leadership, as few real consequences ever materialized. The Administration would seemingly follow in line with then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s 2009 advice that pressing China on human rights “[would] interfere with the global economic crisis, the global climate change crisis, and the security crisis.”

In this respect, the U.S. oversaw a continuation of the Bush administration’s policies that deepened the entanglement of its economy with China’s during the Obama administration. Yet, many of the issues were left to be addressed more aggressively by the Trump administration, such as intellectual property theft. Biden has spoken ill of many of these practices, calling it “outright theft” during annual negotiations in 2013, and had even taken credit for numerous WTO enforcement actions filed against China. To establish a regional economic counterweight to China, he spearheaded with Obama, and ardently defended at the time, the Trans-Pacific Partnership in order to work with strategic allies, such as Japan, Canada, Mexico, and others. However, critics of this Partnership, which included many Democrats, argued that it could further exacerbate American job losses overseas.

From 2013 through the end of the Obama Administration in 2016, security issues would arise between the two countries that Biden directly negotiated on, particularly regarding the South and East China Seas. For instance, following China’s announcement of an Air Defense Identification Zone in the East China Sea in November 2013, which overlapped with Japan’s ADIZ, Biden met with Xi Jinping for five and a half hours to try and maintain stability in the region. Although Biden did not go so far as to call for a rescission of the zone, America’s military has consistently ignored it by conducting flyovers. Similarly, in the South China Sea, the Obama Administration began its policy of pushing back on China, particularly after late-2015 when it publicly trumpeted its Freedom of Navigation Operations. Biden has been unequivocally consistent on this issue, such as during his 2015 commencement speech at the US Naval Academy, “In the disputed waters of the South China Sea, the United States does not privilege the claims of one nation over another. But we do – unapologetically – stand up for the equitable and peaceful resolution of disputes and for the freedom of navigation.”

According to many of their campaign website’s plans, President-elect Joe Biden and Vice President-elect Kamala Harris intend to ramp up government spending in several ways to revitalize the American economy. Although their campaign website does not frequently mention China, there are a few documents that stand out. These policies have potentially enormous implications for the U.S. economic relationship with China that could disrupt global supply chains if they were to come to fruition as they appear on paper. For a better understanding of Biden’s China policy plans, the following policy documents are the most clearly laid out positions to date that he has released thus far.

Unlike most policy positions on his website, the Made in All of America page mentions China frequently. His introduction boldly states, “he will create millions of new manufacturing and innovation jobs throughout all of America.” To do this, his plan intends to make a $400 billion procurement investment in concert with the Biden Clean Energy and Infrastructure Plan, invest $300 billion investment in R&D technologies related to electric vehicles, 5G, and artificial intelligence, and take steps to reduce dependency on China by bringing back what he calls “critical supply chains.” These critical supply chains refer to a variety of intermediate to final goods, such as pharmaceuticals, medical and personal protective equipment, and rare earth minerals used in the production of high-tech goods like cell phones.

Biden’s pledge to target Chinese trade practices in order to protect US technology and intellectual property remains unclear as to how it will occur in practice. However, a firm pivot towards wielding non-tariff measures to combat these practices is likely. These could include US government intervention for legal action against Chinese firms violating contracts or slapping sanctions on those firms or individuals to block future access to the US market. Additionally, Biden will seek to regain the U.S.’ footing and former prominence in international institutions, such as the World Trade Organization, as a way of wooing European and other Asia-Pacific countries towards applying unified pressure on China through WTO dispute mechanisms. However, as WTO and other international dispute mechanisms tend to move slowly, Biden will still likely prioritize US policy solutions, such as sanctions, duties, and controls. With this in mind, the Biden administration is likely to encourage its allies to join the US in hampering or outright excluding Chinese inward investment flows to the US, particularly in high-tech sectors, which would make it much harder for US firms to export sensitive technology to China. However, this will differ from Trump policy, which overemphasized slowing China down over ‘speeding’ America up. Thus, Biden would seek to build coalitions with strategic allies in order to provide a real alternative to China, which could place more emphasis on initiatives like the Blue Dot Network that have largely been left to languish under the Trump administration.

Biden has pledged to not only rejoin the Paris Agreement, but up the ante on US climate pledges so that the US will once again be seen as a global climate leader. On climate and energy issues as they relate to China, Biden has historically attacked China on its development of coal plants. Biden has been quoted since 2013 as wanting to pressure China to transition from coal to natural gas to address its CO2 emissions. That being said, domestically he has historically voted to remove oil and gas exploration subsidies. Biden’s Clean Energy and Environmental Justice Plan closely mirrors his voting history and past quotes insofar as they pertain to China. Biden emphasizes that the US must outpace China on renewable energy investments and also claims that he “will rally a united front of nations to hold China accountable to high environmental standards in its Belt and Road Initiative infrastructure projects, so that China can’t outsource pollution to other countries.” Though this rhetoric is confrontational to some degree, this is actually an area where we will see a Biden administration seeking to work in a strategic manner with China, as climate supporters recognize that China is a crucial component to meeting the Paris Agreement’s goals.

To date, Biden’s released policy papers and rhetoric have been noticeably light on financial services compared to other areas he has spoken on. Biden has professed an embracement of progressive banking policies, but it remains largely unclear how exactly it will all play out. Presently, the most comprehensive policy platform to date on financial services is the Biden-Sanders Unity Task Force Recommendations. Biden’s intention to create a Public Credit Reporting Agency housed under the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is one prominent example of potential disruptions to this industry. There are still very few specifics on how it will function though.

The U.S. has been trying to ensure that dangerous levels of consumer data are not co-mingled with Chinese networks. Despite this, the last couple of years have seen increased entanglement between financial services, such as the partnership announced between PayPal and UnionPay in January 2020. Additionally, the Phase One Trade Deal also required China to lower financial market barriers and give the green light to enterprises like American Express, MasterCard and Fitch Ratings to enter its market. Although China had long promised to open up its domestic payment services to foreign firms, PayPal is the first overseas company to acquire an e-payment license. However, even though decoupling is likely to continue under Biden, it is still early to fully grasp the extent he will impact these emerging partnerships with Chinese financial firms. AliPay and WeChatPay remain behemoths in the Chinese domestic fintech market, so it will take time for PayPal to find its footing in China, if it ever does.

Finally, at a strategic level, Biden has walked back some of his past flowery rhetoric on his relationship with Xi Jinping. Most prominently, he lambasted Xi during the tenth Democratic debate on February 25, 2020, calling him a “thug” and that China “must play by the rules”. Although Biden’s campaign website is relatively barren in terms of his plan for global security, a few important details can be found.

Biden has gone on record indicating a clear willingness to engage in a military buildup in the Pacific to quell China’s growing antagonism, saying that “We should be moving 60% of our sea power to that part of the world to let, in fact, the Chinese understand that they’re not going to get any further, we are going to be there to protect other folks. Michele Flournoy, considered to be a top contender for Biden’s Secretary of Defense, has not so subtly hinted that she would promote a serious arms race against China as a deterrent. In a Foreign Affairs article she published in June 2020, she suggests that if the US military gains the capability to “sink all of China’s military vessels, submarines, and merchant ships in the South China Sea within 72 hours”, then China would be far less likely to engage in actions considered to be overly aggressive. Yet at the same time, Biden recognizes the need for the U.S. and China to cooperate in other areas of global security, the Korean Peninsula in particular. When asked how he plans to handle the North Korea issue, he responded that he would meet with Xi Jinping in China to work towards a solution that prevents the rogue nation from continuing to launch missiles or conduct other inflammatory actions. This intention is echoed in the Biden Plan for Leading the Democratic World to Meet the Challenges of the 21st Century.

On January 20, 2021, Joseph Biden will become the 46th President of the United States of America – at a time when the US and China are intensely renegotiating their relationship, for better or for worse. Although some of this can certainly be attributed to the policies of the Trump Administration, many of these economic, societal, and security issues between the two countries were already on a collision course before Trump took office. In some respects, Trump merely acted as an accelerating force.

Regarding Vice President-elect Kamala Harris, her priorities are much clearer. Nearly all of her legislative co-sponsorships and votes on issues regarding Chinese human rights violations in Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and Tibet, as well as her opposition to allowing Chinese companies like Huawei to conduct business in the US, indicate that she will likely attempt to hold Biden in alignment within those same areas. Harris was quoted by the Council on Foreign Relations in 2019 saying “ we will cooperate with China on global issues like climate change, but we won’t allow human rights abuses to go unchecked.” She also recognizes that strategic cooperation with China on select issues is necessary to solving global issues like climate change and denuclearization in the Korean Peninsula.

For much of his political life, President-elect Joe Biden has been a walking contradiction on China policy, shifting values as needed to achieve policy goals. For instance, on the one hand, he played a leading role in setting the stage for the current state of the U.S.-China relationship during his long tenure as a Senator and as Chair of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations that caused hundreds of thousands of American jobs to move overseas. On the other hand, he has now laid out a plan to bring back American jobs. Similarly, on the one hand, Biden has repeatedly condemned China’s record on human rights, yet on the other hand he was quick to vote against any amendment that would hold China accountable if it potentially jeopardized establishing normal trade relations during the passage of the U.S.-China Relations Act of 2000. Biden has been cautious to reveal too much of his foreign policy agenda on China within his campaign website compared to his painstakingly detailed domestic plans. As he assumes office on January 20th, the question remains whether a renewed “Pivot to Asia”, dubbed by some as an unfinished legacy of the Obama administration, will truly come to fruition under a Biden administration.

[1] *Note* This database was developed from the best publicly available online records from the Library of Congress. As some of these records have not been fully updated online, some votes or bill sponsorships may be unintentionally omitted from our records as a result. Additionally, as Congressional voting records pre-1989 are typically unavailable online, Biden’s voting record from 1972-1988 was unable to be considered for this publication, as visiting a federal depository library during the pandemic was considered inadvisable.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2026 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Trump’s Maritime Insurance Gambit Signals a New Phase in U.S-China Competition