Key Takeaways of Mr. McCahill’s Discussion:

1) The ‘building blocks’ of Chinese leadership are a person’s pedigree, lineage and background

Mr. McCahill began by explaining a research journey he and a fellow diplomat began exploring in the 1980s on the makings of a leader in the People’s Republic of China. Given that any book on leadership they found in China were by-and-large transcripts of ‘great speeches,’ they soon gathered that ‘leadership’ means something far more different than what they first imagined. In significant contrast to the Western model, potential Chinese leaders are selected and groomed, often from their youth, and given posts based on their Party connections more often than personal merit.

2) There are three ‘eras’ of the mid-20th century that explain the shifts in Chinese leadership

Mr. McCahill painted three eras of the mid-20th century that modern Chinese leaders grew up in and how their differing education and socio-economic environments inherently shaped the views they had on the world and the CCP.

First are the leaders who grew up in the pre-1949 era of the Republic of China. This era featured liberal Western education, the free market of ideas, open commerce, science and art. These “genuine Chinese patriots,” as McCahill recalls, are exemplified in Zhu Rongji and Jiang Zemin who were amiable to the West and led China into the 21st century.

Second are the leaders who grew up during the 1950s and 1960s era right after the CCP took power. A new and vulnerable state, the CCP adopted many Soviet models, destroyed Western influences, and forced an industrial focus on their economic structure. Hu Jintiao and Wen Jiabao grew up in this era, being educated early-on under the ROC system and later under the strict Soviet model.

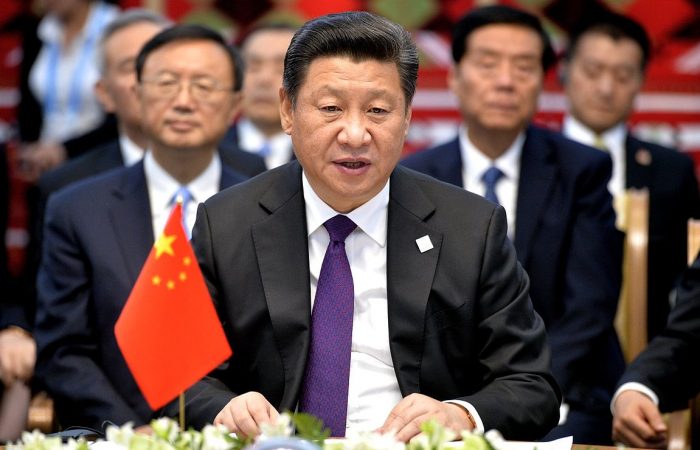

Third are the leaders who grew up during Mao’s Cultural Revolution of 1966-1976. This was an era of chaos for the country; education came to a standstill, violence was abundant, and nationalist fervor and staunch mistrust of the West were ingrained in the population’s mindset. Xi Jinping chronologically belongs to this “Lost Generation” but, despite the period of dislocation during his educational career, found a valuable position in the Ministry of Defense, likely through his father’s assistance.

3) The CCP’s “common corporate culture” permeates all echelons of society and demands conformation

Instead of possessing Western criteria like decisiveness, courage, intelligence, a commanding presence, curiosity, initiative, or ruthlessness, to be successful in the CCP, you must excel in four things: 1) showing deference to the Party, 2) being reluctant to biaotai, or speak out against the leader, 3) perfecting self-criticism without confessing faults, and 4) readily socializing after-hours. Anyone who does not conform to these criteria—or has spent too long a time exposed to Western systems abroad—will, at best, lead a limited life and career within or without the Party.

4) China has changed, and the United States must change in response

Mr. McCahill concluded by stating “[o]ur cardinal error was that we didn’t read China’s history closely enough” and advising that this needs to change. Xi Jinping’s policies and actions become less surprising when you place them in context of his past work (i.e. purging religion as a governor) and paranoia.

Thoughts to Consider:

- The last two decades have seen three shifts in leadership outlook, but what are traits and trends that have not changed? Nationalism? Self-protectionism? A reverence to past great Chinese leaders?

- If potential leaders are ‘groomed’ from youth, are they ultimately controlled like puppets even if they seem to retain their own autonomy and decision-making?

- How does understanding Xi Jinping’s background change how the West approaches discussing the current trade talks and other contentious issues? How should it?

- What about a fourth era? Is it possible to predict when and how an upcoming generation era of leadership—perhaps those that grew up in the economic reforms of Deng Xiaoping—might change? Mr. McCahill predicted that the next leadership will simply be copies of the present leadership.

- Has Xi Jinping’s elimination of the presidential term limit and the CCP’s sheer power of coercion slowed or even eliminated these upcoming generations’ influence? Has Xi’s purging of the party and military made him a target, or has he and his predecessors done enough to build a military committed to the CCP?

- On the topic of Xinjiang, Mr. McCahill believes that Xi Jinping and the CCP regime is “nothing if not arrogant” and are “convinced…that they can keep this [surveillance] going for a long time…and that everything has a price.”-The concept of including ‘pedigree’ in political leadership qualifications is not an estranged notion in the United States. Many national leaders of the 20th century (i.e. Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt, Allen and John Foster Dulles, Jack and Robert Kennedy, George H.W. And George W. Bush) are related by familial ties. What is the difference between this practice and its Chinese equivalent?