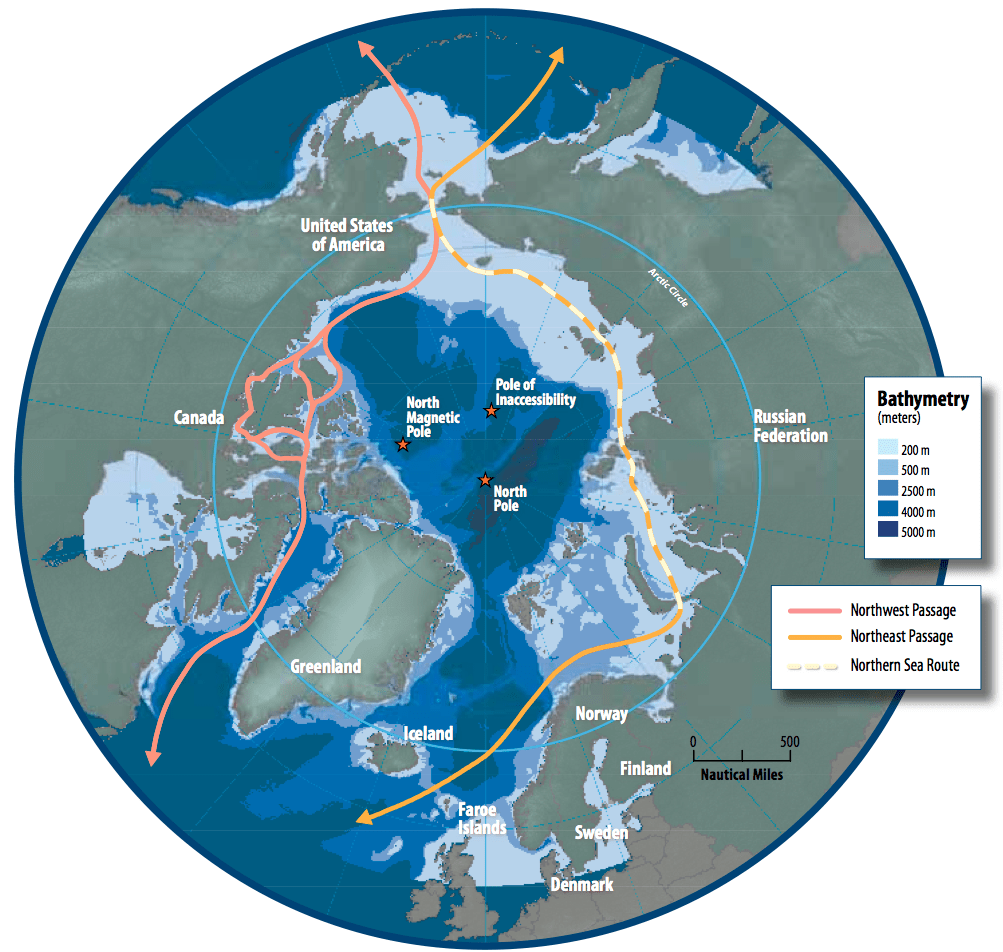

Since the Northeast Passage is bilaterally adjoined by and entirely encompasses the NSR, the Northeast Passage itself is also sometimes simply referred to as the Northern Sea Route. Being located entirely within Russia’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ), the Northern Sea Route is defined by Russia legislation as lying east of Novaya Zemlya and running along the Russian Arctic coast from the Kara Sea to the Bering Strait. The Arctic Council, the primary international governance organization for the region, has also identified the Northern Sea Route as a unique section of the Northeast Passage that only extends up through to the entrance of the Bering Sea.

The Russian Federation is generally responsible for the governance over the NSR. Much of this coordination and governance is conducted through Russia’s Northern Sea Route Administration, founded in 2013, and the Northern Sea Route Association, which Russia founded in 2001; the latter of which includes over 50 organizations both from Russia and foreign countries. Still, there are multiple regional and foreign parties who are active in or discuss the NSR; most notably local Arctic players, the Arctic Council, China, China Ocean Shipping (Group) Company (COSCO Shipping), Maersk Line and, more recently, India.

Unsurprisingly, the Northern Sea Route has been gaining attention in recent years from global warming and expanding technology expanding access to the region. The most frequently cited interest in the NSR is its potential as part of the Northeast Passage to shorten the distance of travel from Rotterdam to Yokohama by more than one-third. This translates into accelerated travel time and subsequent decreases in fuel consumption, gas emissions, and overall costs. There are also fewer risks of falling prey to piracy compared to following the current route that passes through the Suez Canal. There are still researchers who argue that this assessment of the NSR’s potential impact on global trade is an overestimation due to the many challenges from aspects such as regional governance and unexpected navigational issues from bathymetry and climate.

Regardless of whether or not they will restructure global shipping, the changes happening in the region are irrefutable. Ice cover in this region has been reduced by 32% since the 1960s and shipping companies are increasingly more confident in using the route. In 2011, only four commercial ships used the NSR. The following year, 46 ships sailed the entire length of the NSR. Jumping to 2019 and 2020, 277 and 331 vessels, respectively, used the route; both record numbers of full transits for the NSR. And, despite an early freeze-up, 2021 was the Northern Sea Route’s busiest navigation season yet, with most of the vessels being non-Russian. Current projections show that Arctic sea lanes may be ice-free in the summertime as soon as 2035 with ice cover in the Northwest Passage reaching one if its lowest levels in September 2022.

Consequently, concern for, political interest in, and commercial exploration of the region has rapidly grown in the last decade. Russia is the most active party in the NSR—which is understandable and expected given that the NSR runs along Russia’s coastline—and recently announced an estimated 1.8 trillion roubles (US$30 billion) will be spent on a Northern Sea Route development project set to run through 2035. While Russia’s icebreakers have been recorded as being particularly active, many observers are paying more attention to Russia’s recent uptick in military activity, defensive naval drills, submarine tests, infrastructure repairs and renovations along the route and in the Arctic as a whole. Roscosmos, Russia’s premier space administration, has also been brought in to support and improve satellite navigation and other technological advancements.

Also, Russia’s military expansion along the NSR has caught the attention of several regional and extra-regional parties. This expanding global interest in the NSR likely led Russia to formally create the Council of the Northern Sea Route Shipping Participants, the first meeting of which was held at the 2022 Eastern Economic Forum (EEF) on September 6, 2022. This Council was explained as necessary to address “the need for coordination of actions in order to build effective work on the NSR to develop optimal mechanisms for managing Arctic shipping between consignors, shipping companies, the state, and infrastructure operators providing communication, data on the state of ice sheets, weather conditions.”

While Russia is the main stakeholder in the Northern Sea Route, there are other parties and states—both located within and external to the Arctic Region—who have expressed their own interests and commitments to the NSR; usually as an important shipping route. And, while it seems like it is in its own separate bubble, the activity in and around the Northern Sea Route remains subject to global affairs and ongoing political interactions happening elsewhere in the world. For instance, it was recently announced that China’s COSCO shipping company, along with most other foreign parties, have not sailed on NSR this year; presumably over caution from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine earlier in 2022 and the related sanctions.

Simultaneously, the potential for bilateral cooperation over the NSR periodically appears and will continue to exist. After all, China’s Polar Silk Road—the Arctic route of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative—directly involves the Northern Sea Route and Northeast Passage. As recently as September 2022 at the Eastern Economic Forum, leaders from both China and India expressed direct interest in cooperating with Russia over the Northern Sea Route. And commercial shipping groups from around the world would highly value the benefits of establishing formal cooperation over the NSR.

There are some analysts who are skeptical of China’s long-term intent to remain cooperative in the NSR, believing that an end-game of competition is more likely. And it is true that the U.S. military and its NATO allies have increased their own “aggressive” stances in the region; which is why other observers predict the influx of various powers to the region will bring a flashpoint. These are just some examples of the considerations and attentions being made over the NSR in the last few years.

The increased ice melt only brings more attention to the Arctic and the Northern Sea Route as the melting ice opens up new trade routes and extends the season of open access. And a 2022 study by Brown University concludes that as the ice continues to melt, Russia’s hold on the Arctic at the NSR will loosen; which in and of itself could explain the tightening regulations and expanding military defense along the NSR. It is difficult to pinpoint when the Northern Sea Route will become more readily accessible or to what extent it truly will change global shipping or multinational relations. But it is clear that change is happening to the NSR—be it diplomatic, militant or climactic—and states like Russia, China, India and the U.S. are preparing in the meantime to ensure they come out the other end of it in control.

This Spotlight was originally released with Volume 1, Issue 8 of the ICAS MAP Handbill, published on September 27, 2022.

This issue’s Spotlight was written by Jessica Martin, ICAS Research Associate & Chief Editor of the MAP Handbill.

Maritime Affairs Program Spotlights are a short-form written background and analysis of a specific issue related to maritime affairs, which changes with each issue. The goal of the Spotlight is to help our readers quickly and accurately understand the basic background of a vital topic in maritime affairs and how that topic relates to ongoing developments today.

There is a new Spotlight released with each issue of the ICAS Maritime Affairs Program (MAP) Handbill – a regular newsletter released the last Tuesday of every month that highlights the major news stories, research products, analyses, and events occurring in or with regard to the global maritime domain during the past month.

ICAS Maritime Affairs Handbill (online ISSN 2837-3901, print ISSN 2837-3871) is published the last Tuesday of the month throughout the year at 1919 M St NW, Suite 310, Washington, DC 20036.

The online version of ICAS Maritime Affairs Handbill can be found at chinaus-icas.org/icas-maritime-affairs-program/map-handbill/.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2025 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.