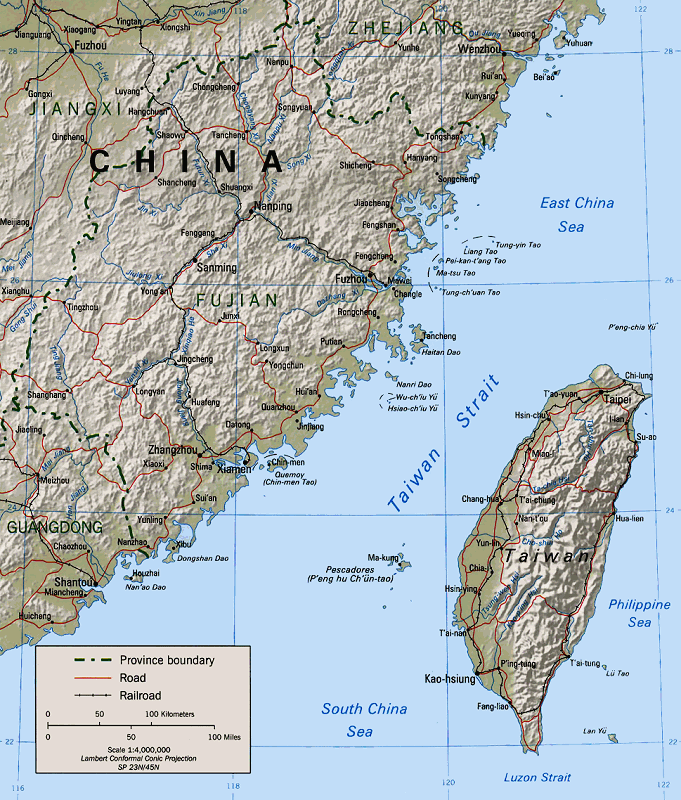

The Taiwan Strait, at a mere 100 nautical miles wide, situated between China’s mainland and the island of Taiwan, has increasingly become a significant roadblock for any potential progress in the U.S.-China relations. While the issue of Taiwan has a complex historical background, the matters that concern the U.S.-China bilateral relations began in 1949. Following the victory of the Chinese Communist Party in the civil war and the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the U.S.-backed Kuomintang (KMT) Republic of China government relocated to Taiwan. Both the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of China (ROC) officially claim both mainland China and Taiwan as part of their respective territories, which makes the island a de facto breakaway province of China today.

As a legacy of the Chinese civil war, the strait of Taiwan has historically been a source of crises between Beijing, Taipei, and Washington. In 1957, the First Taiwan Strait Crisis saw a year-long armed conflict between the two sides of the strait. The armed conflict extended into an artillery blockade of the strait in 1958; also known as the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis. Less frequent bombardment continued until 1979 when the U.S. and PRC officially reestablished their diplomatic relations.

In 1972, the U.S. and PRC jointly released the Shanghai Communiqué, which is the first of a series of three communiqués—formal statements mutually agreed upon by two nations—that laid the foundation of the rapprochement between Beijing and Washington. In the Shanghai Communiqué, the U.S. first declared its “one China” policy, which has since guided its approach to China and Taiwan. The U.S. declared that “all Chinese on either side of the Taiwan Strait maintain there is but one China and that Taiwan is a part of China. The United States Government does not challenge that position. It reaffirms its interest in a peaceful settlement of the Taiwan question by the Chinese themselves.”

In addition to the three joint communiqués, the U.S. Congress passed the Taiwan Relations Act in 1979, which reaffirmed the U.S. commitment to assist Taiwan with the capacity to “resist any resort to force or other forms of coercion that would jeopardize the security, or social or economic system, of the people of Taiwan.” Furthermore, the U.S. unilaterally clarified its position in its 1986 joint communiqué with the PRC with the Six Assurances. The “one-China” policy, the Taiwan Relations Act of 1979, and the Six Assurances are the items that continue to guide Washington’s China and Taiwan policies—and thus, that of the Taiwan Strait—today.

Under the Trump administration and the Biden administration, the tensions have continued to rise in the Taiwan Strait as a combination of changes in China mainland, Taiwan, and the U.S. that shift the balance of power and political landscape in the region. China’s power continues to grow and Beijing is becoming increasingly assertive on territorial issues. The pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) replaced the KMT to be the leading party in Taiwan. Unlike her predecessor Ma Ying-jeou, Taiwan’s current leader Tsai Ing-wen takes a harder line towards mainland China. Lastly, the U.S. has shifted into a more competitive position vis-à-vis China as it now sees Beijing as the pacing challenger that “harbors the intention and, increasingly, the capacity to reshape the international order.” The U.S. Navy, together with other U.S. allies, has conducted more frequent transit of the Taiwan Strait under the Trump and Biden administration.

Outgoing Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in August 2022 sparked a new peak of tensions between China and the U.S. over the Taiwan Strait. The high rank lawmaker’s visit, despite repeated Chinese warnings beforehand, triggered an escalated response from Beijing. Beijing launched ballistic missiles over Taipei for the first time in a series of military drills. While the Biden administration insisted that the California legislator has her rights to visit the self-governing island, it did contend that it was “not a good idea.” U.S.-China relations are at a new historical low as China criticizes the U.S. for undermining peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait.

The Biden administration also released mixed signals with regard to Taiwan in 2022. While Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, Secretary of State Antony Blinken, and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan all repeatedly clarified that the U.S. has not changed its “one China” policy and its policies on Taiwan, President Joe Biden has repeatedly publicly stated that U.S. forces will defend Taiwan in the event of a Chinese invasion. Unsurprisingly, the mixed signals and the president’s remarks sparked strong criticism from Beijing.

While the U.S. continues to conduct routine transits of the Taiwan Strait to show its commitment to uphold freedom of navigation in international waters, these routine transits puts the stability of the strait in danger as they coincide with increased and normalized Chinese military operations around the self-governed island since the Pelosi visit. These uncoordinated military operations in the narrow strait will become a huge challenge for both Beijing and Washington during a period when the two countries lack effective and consistent military-to-military communication channels. The strait is seeing more uncertainty in the forthcoming years.

And regarding the strained political relations, they do not appear to be softened in the near future. Prior to the midterm election, the incoming Republican Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy has previously stated that he will visit Taiwan if he becomes House speaker. As the Republican party regained control of the U.S. House, the possibility of another U.S. Speaker of the House—technically the third in line for the U.S. presidency—visiting Taiwan within a year, puts more tension on the U.S.-China relationship. Should McCarthy visit Taiwan in 2023, the U.S.-China relationship will face another severe challenge and the Taiwan Strait could see another crisis on the horizon.

Taiwan’s 2024 Presidential Election could also have a significant impact on not only cross-strait relations but also the U.S.-China bilateral relationship. While the KMT enjoyed a huge victory in Taiwan’s recent local elections, the next leader of the self-governing is still uncertain. The next leader of Taiwan will face huge challenges balancing the tensions between Beijing and Wahisngton, as well as the mounting tensions over the Taiwan Strait.

Last in the main equation is China. China’s growing military capabilities and its desire to reunify Taiwan is not a secret to the West. That said, Beijing continues to stress its hope to resolve the issue of Taiwan through peaceful measures while never renouncing the use of force. Concerns of a potential deadline for resolving the issue of Taiwan by force have been raised in the West over the past year. Minister Jing Quan from the Embassy of China in the United States rejected such speculations at ICAS’ 2022 Annual Conference while restating China’s official position on the issue of Taiwan. On the other hand, at another think tank event U.S. Undersecretary of Defense Colin Kahl said it is unlikely that China has a hard deadline by 2027, but contended that China has its 2027 centenary objectives to become more competitive against the U.S. in the Indo-Pacific region.

This Spotlight was originally released with Volume 1, Issue 11 of the ICAS MAP Handbill, published on December 27, 2022.

This issue’s Spotlight was written by Yilun Zhang, ICAS Research Associate.

Maritime Affairs Program Spotlights are a short-form written background and analysis of a specific issue related to maritime affairs, which changes with each issue. The goal of the Spotlight is to help our readers quickly and accurately understand the basic background of a vital topic in maritime affairs and how that topic relates to ongoing developments today.

There is a new Spotlight released with each issue of the ICAS Maritime Affairs Program (MAP) Handbill – a regular newsletter released the last Tuesday of every month that highlights the major news stories, research products, analyses, and events occurring in or with regard to the global maritime domain during the past month.

ICAS Maritime Affairs Handbill (online ISSN 2837-3901, print ISSN 2837-3871) is published the last Tuesday of the month throughout the year at 1919 M St NW, Suite 310, Washington, DC 20036.

The online version of ICAS Maritime Affairs Handbill can be found at chinaus-icas.org/icas-maritime-affairs-program/map-handbill/.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2025 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.