By Sourabh Gupta

Article Series: China and the G20, China and World Economy

China & World Economy 24:4, July/August 2016

This special issue looks at China’s Presidency of the G20. Several articles analyze the contributions of the G20 to various policy domains in the global economic order and what a Chinese Presidency might entail. One common theme is that China’s presidency gives it the opportunity to demonstrate that it can be a global economic leader, particularly in advancing the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals, rebalancing its own economy to ensure international financial stability, and strengthening the BRICS’ development agenda.

Report Series: Asian Alliances Working Paper Series

Brookings, July 2016

The Brookings Institute released a report series on America’s alliances and security partnerships in East Asia as part of their “Order from Chaos: Foreign Policy in a Troubled World” project. Six papers detail the United States’ relationship with Japan, the Republic of Korea, Australia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Taiwan. They seek to address how the US views its partnership with these countries, what security commitments the US has made, whether there are any fears or insecurities in these relationships, and how this alliance is affected by China’s growing influence in the region.

China’s Evolving Approach to Economic Diplomacy

Timothy R. Heath

Asia Policy No. 22, July 2016

Timothy Heath considers how China’s approach to economic diplomacy has changed after the global financial crisis, noting its reforms to further integrate Asian economies, modify international trade rules and secure the resources needed to maintain China’s competitiveness. Heath argues that these reforms have injected strategic competition into the US-China relationship, and that US-Chinese economic interdependence may not be enough to diffuse this competition. Due to this, Heath concludes that disputes between the US and China may be more difficult to solve and suggests that the US should seek ways to participate in the Chinese-led economic initiatives such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and increase dialogue with China over international norms.

Hopes of Limiting Global Warming? China and the Paris Agreement on Climate Change

Anthony H. F. Li

China Perspectives, 2016/1

Li argues that China is cooperating in the global climate change regime because climate change is crucial to China’s own domestic development. The 21st Conference of Parties (COP 21) concluded a legally binding document which bound the 195 participant countries to limit global warming to 1.5°C. However, Li warns that there is still a lingering disagreement on assigning fair responsibility regarding limiting global warming between the developing countries (a bloc led by China and India) and the developed countries (a bloc led by the US.)

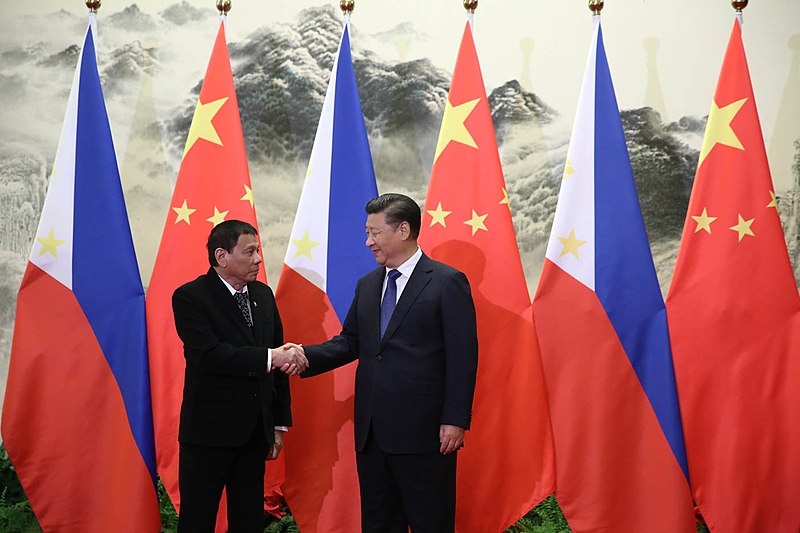

What the United States and China should do in the wake of the South China Sea ruling Jeffrey Bader

Order from Chaos, Brookings, July 13, 2016

Bader offers practical policy suggestions for both the US and China in response to the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s ruling that upheld most of the Philippines’ claims in the South China Sea maritime rights disputes. Bader proposes that the US should support dialogue between China and the Philippines to reach a mutually beneficial compromise, such as shared fishing rights. The US should also decrease freedom of navigation exercises near Chinese installations. For China, he suggests that China should make clear it will not engage in any military action against the Philippines. Bader stresses that the US and China must discuss issues such as the use of force, defining militarization, and strengthening the bilateral relationship.

What China Can Learn from the South China Sea Case

Zheng Wang

Wilson Center, July 14, 2016

The author makes a number of observations about Chinese foreign policy following upon the setback dealt by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Philippines v. China case earlier this month. He notes that the counterproductive decision not to participate in the arbitration may be the result of top leadership not receiving the right information or advice from within the foreign policy establishment. He also notes that China has few international law experts and a poor record of historical and policy research. These factors ultimately led to China’s refusal to participate in and inability to influence the arbitration process. Another problem the author observes is China’s relative inability to communicate its positions to the outside world, and the lack of Chinese communicators who can go beyond repeating official positions and effectively persuade or convince foreign audiences of Chinese views.

US Needs a New South China Sea Strategy to Contain Beijing

Jennifer Harris

Newsweek July 17, 2016

This article maintains that the US must develop a new strategy to counter China in the South and East China Seas following upon the recent arbitral ruling in the Philippines’ case against China. While China is engaging in a strategic economic match in the region, the US has focused its strategy on military dominance in the Pacific. For example, Beijing prefers to use economic power to pressure other claimants in the South China Sea. Harris suggests that a wise strategy for Washington would be to help its Asian allies to avoid economic over-dependence on China, which would limit the effectiveness of China’s economic “bullying.”

Shaping China’s Response to the South China Sea Ruling

Bonnie Glaser

The National Interest, July 18, 2016

Glaser outlines different possible courses for Beijing to follow after the Hague’s ruling in the Philippines v. China case. She notes that escalatory responses might be more likely if China feels “cornered by the US and its allies.” She recommends carefully calibrating future FONOP activities, and limiting publicity surrounding them. Glaser also suggests giving China space to clarify the nine-dash-line in ways that comport with UNCLOS rather than announcing that it is invalid, and asks the US Senate to ratify UNCLOS.

How China’s “Currency Manipulation” Enhances the Global Role of the US Dollar

Michael Pettis

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, July 22, 2016

Pettis considers the implications of China releasing reserve data denominated in the Special Drawing Rights (SDRs). This announcement has caused some money watchers to believe that China is challenging the current global financial order and the predominance of the US dollar. However, Pettis argues that China’s monetary policy over the last several years has actually been enhancing the reserve role of the dollar, and that it is in China’s best interest to do so to maintain its own economic development. Pettis does suggest that due to long-term trends in the global economy, the US may eventually need to limit foreign access to reserve bonds, or change international trade rules in response to Chinese monetary policy.

Before Moving to “No First Use,” Think About Northeast Asia

Jonathan Pollack and Richard Bush

Order from Chaos, Brookings, July 20, 2016

One pillar of the Obama administration’s national security strategy is a US commitment to non-proliferation in an attempt to achieve a nuclear-free world. As President Obama approaches his final six months in office, a major nuclear weapons policy shift may include a “no first use” policy. Richard Bush and Jonathan Pollack find that such a major policy shift may be difficult to achieve due to lingering security threats in Northeast Asia. The authors support the idea that a nuclear no-first use policy would degrade security assurances to US allies in the region.

China’s Engagement in Africa: From natural resources to human resources

Brookings, July 13, 2016

David Dollar and Wenjie Chen discussed trends in China’s investments and engagement in Africa. The panel found that, as China shifts to a sustainable economic model, its hunger for raw materials will continue to decline. This change in natural resource demand has begun to impact commodity-based African economies that are dependent on the export of natural resources. The authors of the Africa Growth Initiative’s study “China’s Engagement in Africa: From Natural Resources to Human Resources” argued that China has helped to drop the overall poverty rate in Sub-Saharan Africa, but it must be more effective in its next phase of engagement.

The Obama Doctrine and Asia

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, July 19, 2016

Derek Chollet and Kurt Campbell discussed their recent books on President Obama’s foreign policy. Chollet was supportive of the “Obama doctrine,” the idea that the United States must better come to terms with the practical limits of its power. Campbell, whose book deals with the “pivot to Asia,” discussed some of the rationale for the policy. He noted that the pivot or “rebalance” must be understood in the context of Obama’s acknowledgement that the US had to prioritize key regions in its foreign policy. He described the pivot as being regionally focused, rather than centered on China. He observed a tendency in some other administrations to see Asian politics as a US-China “G2,” but claimed that the pivot sought to avoid this with a broader view that acknowledges the importance of Asia in the coming decades.

Fifth Annual Conference on the South China Sea

Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 12, 2016

This conference considered the situation in the South China Sea (SCS) from a legal, military, and environmental perspective, focusing specifically on the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s (PCA) award on the Philippines v China case, which was released just that morning. The recurring themes at the conference were the implications of the PCA’s decision, the US’ commitment to freedom of navigation, and how China would respond to this decision. Legal panelists noted that the PCA had accepted thirteen of the Philippines’ fifteen claims and wondered whether this decision would lead to any changes in Chinese policy. Military panelists and Guest Speaker Senator Dan Sullivan called for stronger US military presence in the region, but stressed that this presence was merely to ensure freedom of navigation in the seas, not to antagonize China. All panelists reaffirmed the US and China’s commitment to peaceful settlements of disputes. Experts on the environment expressed concerns with the PCA’s classification of all land forms in the SCS as rocks, which could lead to an uptick in fishing and further destroy coral reef ecosystems in the area. The conference concluded with remarks by Chinese Ambassador Cui Tiankai, who denounced the award because China had not consented to the arbitration and believed the PCA had exceeded its own jurisdiction by ruling on territorial issues.

China and the G20

CSIS, July 20, 2016

This event discussed the US and China’s goals at this year’s G20 meeting, where panelists noted areas of cooperation and raised their concerns about a Chinese presidency. Some panelists described commercial relations as the “bright spot” between the US and China, and identified the G20 meeting as a “brief window” in which both countries could set aside internal politics to collaborate on global issues. Panelists noted that China’s goals at the G20 to boost innovation, sync trade and investment policy, and reform multilateral institutions were evidence that China wants to engage in the international system. However, some panelists expressed concerns that China’s power and difficulties presented by its domestic economic reforms could be potentially disruptive to the global system.

Is the United States Losing China to Russia?

Brookings, July 26, 2016

J. Stapleton Roy, Fiona Hill, and Yun Sun described shifts in the US/Russia/China trilateral relationship, including historical ties and conflicts between the three countries. Roy noted that even though China was alarmed by Russia’s annexation of Crimea, their common interests— notably an aversion to a US-dominated unipolar system—have brought them closer together than ever before. This relationship is nonetheless limited: Roy argued that neither Russia nor China have any interest in forming an anti-American alliance relationship.

By Sourabh Gupta

In 1986, a late-thirty-something Harvard-trained American lawyer won a significant judgment at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) against the United States for having interrupted peaceful maritime commerce and violated customary international law. Almost 30 years to the day after this ruling in Nicaragua v. The United States, Paul S. Reichler pulled off yet another momentous victory at The Hague – this time against China for having breached its international treaty obligations in the South China Sea.

Washington refused to honor the award, citing Managua’s selective application of the law, the highly-charged political nature of the case and the ICJ’s over-reach in asserting jurisdiction. Later that year, it cast the sole veto against a United Nations Security Council draft resolution that had called for full and immediate compliance with the judgment. China was one of 11 states on the Council to vote in favor.

Although Beijing today restates each of the accusations made by the defense that day, one nevertheless hopes that it will set a better example of compliance than Washington. It is also in its enlightened self-interest to do so. The political cost-benefit calculus underlying its emerging policy of ‘non-acceptance of award but escalation control on ground’ (coupled with the offer to negotiate) will gradually but decisively shift against it with each passing month – especially as Manila forces the issue in order to collect on the benefits conferred by the award. Hanoi too stands advantageously poised to force its claims in court that it enjoys traditional fishing rights within the territorial sea of the Paracel Islands and, further, that none of the high-tide features there is a fully-entitled island.

China must discreetly implement an ‘early harvest’ set of compliant actions within the framework of its ‘dual track’ approach to managing the South China Sea disputes. These could include allowing re-entry of traditional Filipino fishermen to the territorial sea of the Scarborough Shoal, withdrawing its para-military presence from the Second Thomas Shoal area, and limiting its fishing moratorium to the 12 nautical mile limit from appropriable features. Beijing should also seize this opportunity to clarify the geographic limits of its ‘relevant waters’ claim in the South China Sea as well as the functional nature of the individual and non-exclusive ‘historic right’ of access that it seeks in these waters.

ASEAN too must brace for the near and medium-term implications that stem from the July 12 award, particularly on the security front. The tribunal’s decision to annul all extended maritime claims associated with China’s land features on the Philippines’ continental shelf is most usefully seen as an endorsement of an April 2009 joint submission filed by Malaysia and Vietnam to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS), which too had implied that none of these land features in the Spratly’s group was capable of generating exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and continental shelf rights. That filing had taken China by surprise and touched off a protest note featuring the Nine Dash Line and assertive enforcement actions thereafter within that perimeter. The tribunal’s ruling is likely to encounter a similar if not greater show of resolve by Beijing – both on the table and at sea.

Sovereignty-linked issues of jurisdiction have always been tied to a larger political calculus of stability and good neighborliness and China’s rulers have not been shy to calibrate their stance between a hardline and a flexible one to suit the strategic circumstances at hand. Should Filipino “armed forces or public vessels” provide escort to private efforts to unilaterally re-start oil and gas development activity on its now-legally undisputed continental shelf, the United States too could be formally drawn into the line of fire – with cascading implications for peace and stability in the South China Sea.

Second, the tribunal’s award calls into question the oft-regurgitated call to expeditiously conclude a China-ASEAN “Code of Conduct” (COC). The area of application of the COC’s rules was premised on the existence of unresolved maritime boundary areas of the parties concerned in the South China Sea. Having produced a de facto delimitation of the China-Philippines maritime boundary in the South China Sea by the back door (and furnishing principles for the China-Vietnam one too), the tribunal has effectively undercut the raison d’etre that sustains the envisaged Code. Both ASEAN and China would be better-off re-framing their COC interactions to a trimmed-down dialogue on preventive mechanisms that sets and stabilizes the rules of engagement and communication for their paramilitary forces at sea (on the lines of the multi-national Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea).

Third, the scope for functional cooperation in the South China Sea has been set back in no uncertain terms – although by no means erased. Had the tribunal ruled Itu Aba to be fully-entitled island, it could have facilitated a mutually enlightened self-interest basis for oil and gas joint development in the overlapping water areas on the lines of the now-expired tripartite

Joint Marine Seismic Undertaking (JMSU). With no geographic overlap to contend with now – and literally thereby no differences of entitled rights to shelve, shelving differences and seeking joint development has been transformed into a hollow slogan. The contours of functional cooperation will accordingly need to evolve from bilateral actions on oil and gas development and fisheries cooperation to sub-regional activities in cross-cutting areas, such as environment protection, maritime search and rescue, and cooperation against piracy and trans-national crime.

Finally, the arbitration has ripped apart the deliberate ambiguity that had at time helpfully spurred the search for win-win solutions to the region’s overlapping challenges at its peripheries. Yet another Asian frontier has now been transformed into a “razor’s edge on which hang suspended the modern issues of war or peace.” One fears the tenuous quiet in the immediate wake of the award will not last.

As China and ASEAN gingerly pick-up the pieces and attempt to mold a ‘new normal’ in the South China Sea, the two parties stand at an important fork on the road. They can either plump for exclusivist answers to the challenges in their designated maritime zones (the littoral states’ preference) or they can throw their weight behind comprehensive and overarching cooperative frameworks (China’s preference) that secure peace and stability at sea. China and ASEAN must try to form a consensus on this important question. Papering over the gap will be much harder than papering over the language in their annual summit communiques. Muddling through is not an option.

Sourabh Gupta is a Senior Fellow at the Institute for China-America Studies and can be reached at sourabhgupta@chinaus-icas.org. This article first appeared on East Asia Forum.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2025 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.