Starting in 2019, the Institute for China-America Studies and its partners based in China, the United States and Canada began bringing together career experts to share research proposals and dialogue on current events in diplomacy, trade, society, politics and international law in the sphere of China-U.S.-Canada trilateral relations. To further encourage candid and constructive discussion, this roundtable is conducted under Chatham House rules and is invitation only.

This year, the roundtable consisted of two panels: one on ‘Politics & Security’ and another on ‘Technology, Climate & Human Exchanges’. Each panel included career experts—multiple each from China, the U.S., and Canada—who presented on a related subject of their choosing and shared in a moderated discussion with those in their panel.

Executive Summary of The 3rd China-US-Canada Trilateral Relations Roundtable Dialogue

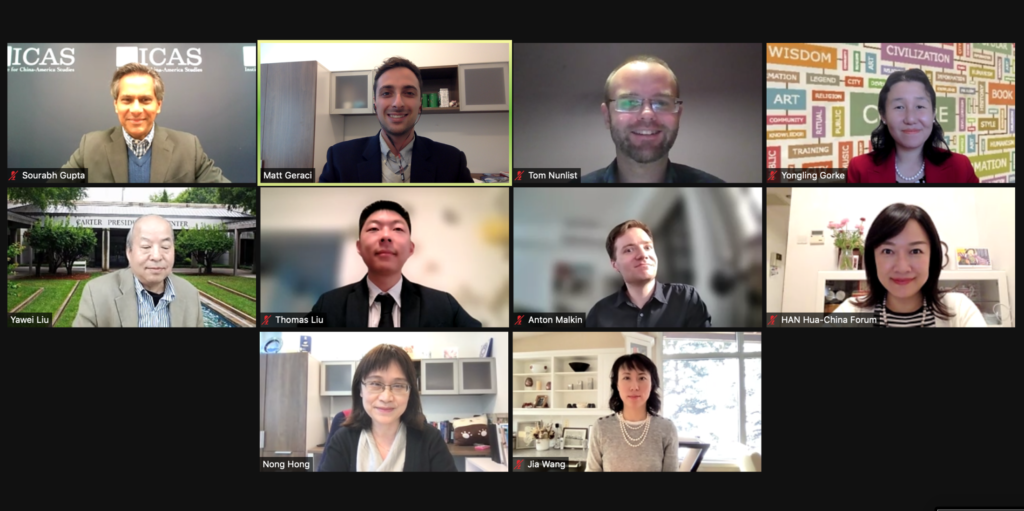

On the mornings of November 17 and 18, 2021, experts and young scholars from China, the United States and Canada convened virtually to share their perspectives on the current status and future trends on what could be done to improve Sino-U.S. as well as Sino-Canada relations within their respective focus areas. The meeting, which was conducted remotely over Zoom across multiple time zones and under Chatham House rules, was a fruitful time to hear varying perspectives and exchange candid views on vital issues impacting the present and future relations.

Day 1 Panel: Politics and Security

The transition of power in Washington and the potential that it brings to healing tensions with China was a topic of interest for multiple speakers. However, it was noted that current bilateral relations are under such a deep systemic strain across almost all fields of interaction that a simple domestic political transition, even one as noticeably far-reaching as that from the Trump administration to the Biden administration, will by itself have only a modest impact. Still, there is scope for change in sight. Since the Biden administration came into power, there has been repeated open acknowledgement from U.S. officials, like U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai, that a full decoupling is unrealistic and would be harmful to both countries. The virtual Biden-Xi Summit held recently is another example of an attempt to, if not repair the relationship, then at least slow the decline of the relationship. Unlike the Soviet Union of the Cold War era, China is here to stay and cannot simply be ignored. All experts agreed that honest discussions–especially high level discussions–are crucial if the U.S. and China are to move forward in a constructive, collaborative manner that ends in cohabitation rather than a decisive victory for any one party.

The current events surrounding Taiwan–depicted as more of a political problem rather than a security problem to Beijing–was highlighted at the roundtable. Despite increasing tensions from new military activities surrounding Taiwan, the imbalanced AUKUS agreement, and outspoken views on both sides regarding the Indo-Pacific, there was a general consensus among the scholars that 1) current events are not about to lead to imminent war in the Taiwan Straits, at least not yet or anytime soon, and 2) the issue of the South China Sea is not currently a top priority of either government. Washington may be outspoken on the topic but it has not changed its basic ‘One China’ policy towards Taiwan, and Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen is ultimately focused on maintaining the status quo for now. Neither Washington nor Beijing is expected to change their position on Taiwan or the South China Sea any time soon, causing the current tensions to remain, which leaves third parties like Canada in the increasingly delicate position of having to choose sides rather than just wait it out. Still, with new agreements like AUKUS being signed, it is vital to maintain a broad-based balance of power or else short-sighted and irreversible decisions could be made in the name of national security.

In a notable shift within Canadian foreign policy that has witnessed it leaning far more West-wards, Ottawa was described as being increasingly conscious of China as a major power and a major competitor–especially since the collapse of the free trade talks in 2018 and the incarceration of the ‘two Michaels’. Simultaneously, the gathered experts predicted that Canada’s current government–a minority government–will prioritize domestic political survival over foreign policy and thus will work towards being more of a facilitator between the two big powers – the U.S. and China – rather than an outspoken challenger as it works to build stronger ties in trade and technology with its Western allies and partners.

Day 2 Panel: Technology, Climate & Human Exchanges

Panel 2, which was held on November 18, centered around areas of U.S.-China-Canada contention and congruence in the realm of technology, climate change, and human exchanges.

Coming on the heels of an unexpected U.S.-China joint statement on climate change towards the end of COP26 in Glasgow on November 10, the prospect of cooperation between the two countries in this area received renewed interest among the gathered experts. However, despite the global fanfare in news media on both sides, there was a consensus amongst the speakers that far too much remains unclear as to what it tangibly means in terms of actual, concerted cooperation between the two sides on climate change. Furthermore, the Biden administration and the Chinese government have made it even less clear where the line should be drawn as to where the joint societal gains of cooperation are outweighed by perceived or actual political risk from cooperative sharing. It was pointed out that for fruitful cooperation to occur between the two countries, there would need to be a verifiable commitment and system for monitoring greenhouse gas data submissions as well as a mutual understanding that climate cooperation and climate competition are not by definition mutually exclusive. At least for the time being, it is clear that the current state of bilateral ties will only allow for selective cooperation on non-contentious research and technologies in the environmental field.

More broadly, while cutting-edge technologies will likely continue to be highly politicized and lead to partial decoupling in select areas, there was a common thread amongst the participants that continued dialogue is the best path forward for governments and the private sector in order to better navigate these dynamic developments – even if dialogue does not produce near-term solutions. In many respects, technology competition does create some positive externalities. For one, it provides not only alternatives for third party nations and industries but also additional incentives for research and development opportunities. Furthermore, looking at the ongoing semiconductor shortage, the push for decoupling and export controls is ever-prevalent. A primary reason for this is that given the high levels of industrial consolidation in the sector, particularly on the production side, there are very few additional well-capitalized firms that are capable of picking up the slack and producing these highly complex technology products on short notice. The technology decoupling drive led by the U.S. has already led to an aligning of incentives among the Chinese private sector and government, leading in turn to a hastening of the push for domestic and self-sufficient alternatives.

The growing gap in data security and governance policies between the U.S. and China is creating an additional challenge for international trade. Third countries, such as Canada, which are indirectly impacted by shifts within the global system, will naturally seek alternatives and are likely to work with a broader range of stakeholders, including Chinese companies. There was a general consensus that the U.S., the EU, China, and Japan, with their influence in determining global policy and standards on these issues, must all remain open to dialogue with each other, and fully consider the impact of potentially adversarial decision making and the splitting apart of technology ecosystems.

Coordination on technology, climate change, and security issues, such as those discussed during both panels, are likely to occur most effectively if each side has a solid mutual understanding of the other. This is where the long-term benefits of human exchanges play out, often as a culmination of years of study and interactions. The panelists noted that the power of people-to-people exchanges, starting from student exchanges, creates a crucial network that allows additional pathways for diplomatic and civil society progress to occur when they fail to produce results in official channels. This being said, recent developments that have witnessed the dismantling of numerous bilateral cultural programs in the United States and China have diminished the future potential for mutual understanding between the two nations. In recent years, despite political difficulties between Canada and China, such as the rise of racial profiling and espionage allegations, the influx of international students has proven to be an economic boon for Canadian universities and businesses, as well as for Canadian students who travel to China. However, it is also important to focus on the societal benefits that international students bring to their host countries post-graduation in numerous fields. This is something to be borne in mind especially at a time of global tragedies such as the ongoing pandemic, which quite naturally has led to a thinning-down of people-to-people exchanges. Yet at the same time, such exchanges are more important than ever before. Global international development initiatives originating in the U.S., such as Build Back Better World (B3W), and from China, such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), have the potential to play a critical role in fostering re-engagement with different parts of the world, and also aid the international economic recovery effort out of the pandemic. With this in mind, it was suggested that, rather than focusing purely on the deficiencies of either initiative, both governments ought to recognize the comparative advantages that BRI and B3W bring to the table for such a purpose.

During the closing statements it was acknowledged that, from the Chinese perspective, many in the country were increasingly disappointed and disillusioned with the West, given the perception that the latter is overly focused on putting-together coalitions that are intended to hamper China’s development in key areas. The panelists were left with a number of questions to ponder as well as a realization that both sides need to find thoughtful new ways to trust each other, to convince each other, and find openings for mutually beneficial engagement.

[Summary written by Matt Geraci, Research Associate & MIT Program Manager, and Jessica Martin, Research Assistant & Communications Officer]