EVENT SUMMARY

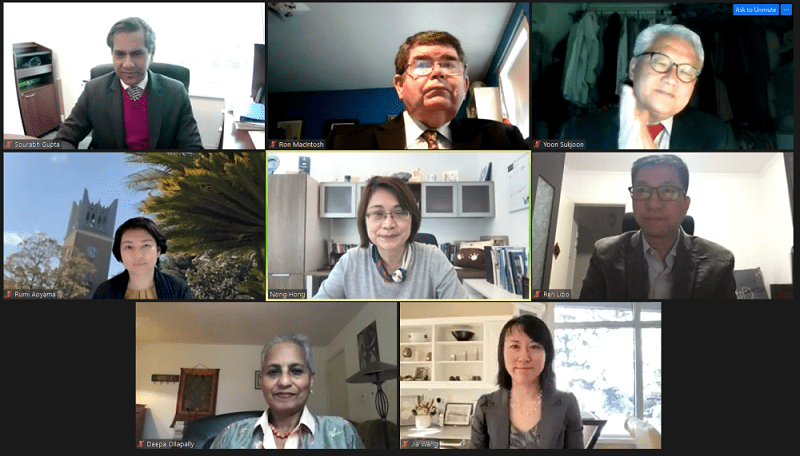

On April 20, 2022, the Institute for China America Studies, China Institute of University of Alberta and Grandview Institution jointly hosted a virtual roundtable on “Middle Power Countries’ Perspective on U.S.-China Relations.” This event brought together scholars representing five middle power countries–Canada (Ron MacIntosh, Senior Fellow at University of Alberta China Institute), India (Deepa Ollapally, Professor at George Washington University), Japan (Rumi Aoyama, Director of Waseda Institute of Contemporary Chinese Studies at Waseda University), South Korea (Yoon Sukjoon, Senior Fellow at Korea Institute for Military Affairs) and Australia (Sourabh Gupta, Senior Fellow at the Institute for China-America Studies)–to present and discuss their country’s perspectives on the increasingly competitive U.S.-China relationship to ultimately build a better understanding of middle power countries’ unique and important perceptions of–and role within–the U.S.-China relationship. Jia Wang, Interim Director of China Institute, moderated the discussion and the following question and answer session. Hong Nong, Director of the Institute for China-America Studies and Ren Libo, Director of Grandview Institution, gave opening and concluding remarks, respectively.

First, Ron MacIntosh provided a background of what it means for a country to be a ‘middle power’ in the current age, with a special focus on Canada’s perspective. He explained how, after the post-World War Two era, Canada found itself among like-minded company, causing it to soon become and remain a valued ally to the United States; a history that inevitably impacts its bilateral and international encounters with China today. In terms of the role of middle powers, MacIntosh explained that, aside from providing economic partnerships and representing the global perspectives that great powers miss, middle powers expand the world’s capacity for creative and collaborative solutions. Simultaneously, middle powers must take great care to not exacerbate the competition–the existential crisis that is currently found in U.S.-China relations. Above all, middle powers cannot sit back but must find ways for their messages to be compelling; otherwise they will not be heard.

Second, Deepa Ollapally shared India’s perspective, starting with an introduction to India’s current outlook on U.S.-China relations. India’s security concern over China has become a factor that aligns New Delhi increasingly closer to the U.S. in recent years. That said, Ollapally does not believe that India is completely committed to form an alliance with the U.S. to jointly counter China. Despite Washington’s increasing promises and commitment to the Indo-Pacific region, Ollapally believes that India does not take the U.S. presence in the region for granted, nor does it believe it can fully count on American support, which may oversecuritize the India-U.S. relationship and thus become provocative to China. India seeks to exercise a level of strategic autonomy, which aligns with its position over the Ukraine crisis. While China may view India’s attitude as a potential opportunity to improve its relationship with New Delhi, Ollapally contended that India may have opposed the United States’ use of excessive sanctions on Russia, but also sees and worries that the crisis is increasingly benefiting China.

Third, Rumi Aoyama introduced Japan’s perception on the U.S.-China relationship. Many view Japan being caught in a dilemma to balance its economic cooperation with China and its security cooperation with the United States. However, Aoyama instead believes that Japan is in a unique position analyzing the U.S.-China bilateral relationship and that Tokyo possesses a strategic leverage over both Beijing and Washington. Contrary to common understanding, Aoyama believes that Japan has a China policy that is no weaker than other U.S. allies (such as Australia) on critical issues such as the South China Sea, Taiwan, and human rights, regardless of Tokyo’s economic relationship with Beijing. Japan does view China as its biggest security concern, and that shared view has placed U.S.-Japan relations at its best point since the end of the Cold War. Still, Aoyama believes that Tokyo is still in a good position to balance between Beijing and Washington. Amid its rising tensions with the U.S., she suggests that China will eventually have to make a stronger effort to improve its relations with other Asia-Pacific neighbors, including Japan, in order to push for regional economic cooperation initiatives such as the RCEP, and that Japan has many potential options.

Speaking fourth, Yoon Sukjoon presented South Korea’s perspective as a middle power. He first acknowledged that, amid the mounting U.S.-China rivalry, it is also becoming increasingly challenging for South Korea to maintain a power balance between the two countries. Simultaneously, Yoon believed that Seoul has been more successful than most other powers in balancing between Washington and Beijing while also maintaining its security and economic interests. He voiced his concern over the newly elected South Korean President Yoon Sukyeol and his foreign policy, however. While President-elect Yoon is vowing to improve South Korea’s ties with the United States, Yoon cautioned how, if the strategic alignment went too far, South Korea could become a scapegoat of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Strategy since its purpose is different from AUKUS and other purely military initiatives. Having too strong a focus on allying with the U.S. to counter China would eliminate the comprehensive strategic autonomy that Seoul has successfully managed for decades. Yoon concluded that South Korea should focus on North Korea rather than involving too much in the U.S.-China great power competition.

Last, Sourabh Gupta provided Australia’s outlook on the U.S.-China relationship, depicting the recent evolution that Australia’s national strategy has been undergoing across the last few decades. He first gave a brief post-Cold War background of Australia’s defense strategy, explaining how recent years have witnessed a near return to an old forward defense policy of strategic thinking that is no longer centered on security self-reliance but on alliances and partnerships. And while Australians do not have much leverage in the direct bilateral relationship, it is a member of CPTPP, which China wants to join, and has recently made the decision to form the AUKUS military alliance with the United States and the United Kingdom. Especially with China’s interest in breaking through the first island chain and preserve the South China Sea as a bastion as well as the concurrent development of nuclear-powered submarines, Gupta concluded by summarizing that Australia has gone from not having to choose to having made its choice, further complicating its role as a middle power amidst the U.S.-China great power competition.

Opening Remarks

Nong Hong – Executive Director, Institute for China-America Studies

Moderator

Jia Wang – Interim Director, China Institute, University of Alberta

Speakers

Ron MacIntosh – Senior Fellow, China Institute, University of Alberta

Deepa Ollapally – Professor, George Washington University

Rumi Aoyama – Director, Waseda Institute of Contemporary Chinese Studies, Waseda University

Yoon Sukjoon – Senior Fellow, Korea Institute for Military Affairs

Sourabh Gupta – Senior Fellow, Institute for China-America Studies

Concluding Remarks

Ren Libo – Director, Grandview Institution

Time Zone Clarifications:

April 20, 10:00 – 11:30 (EST, Washington DC)

April 20, 8:00 – 9:30 (MDT, Edmonton)

April 20, 22:00 – 23:30 (CST, Beijing)

April 20, 23:00 – April 21, 00:30 (KST/JST, Seoul/Tokyo)