Event Summary

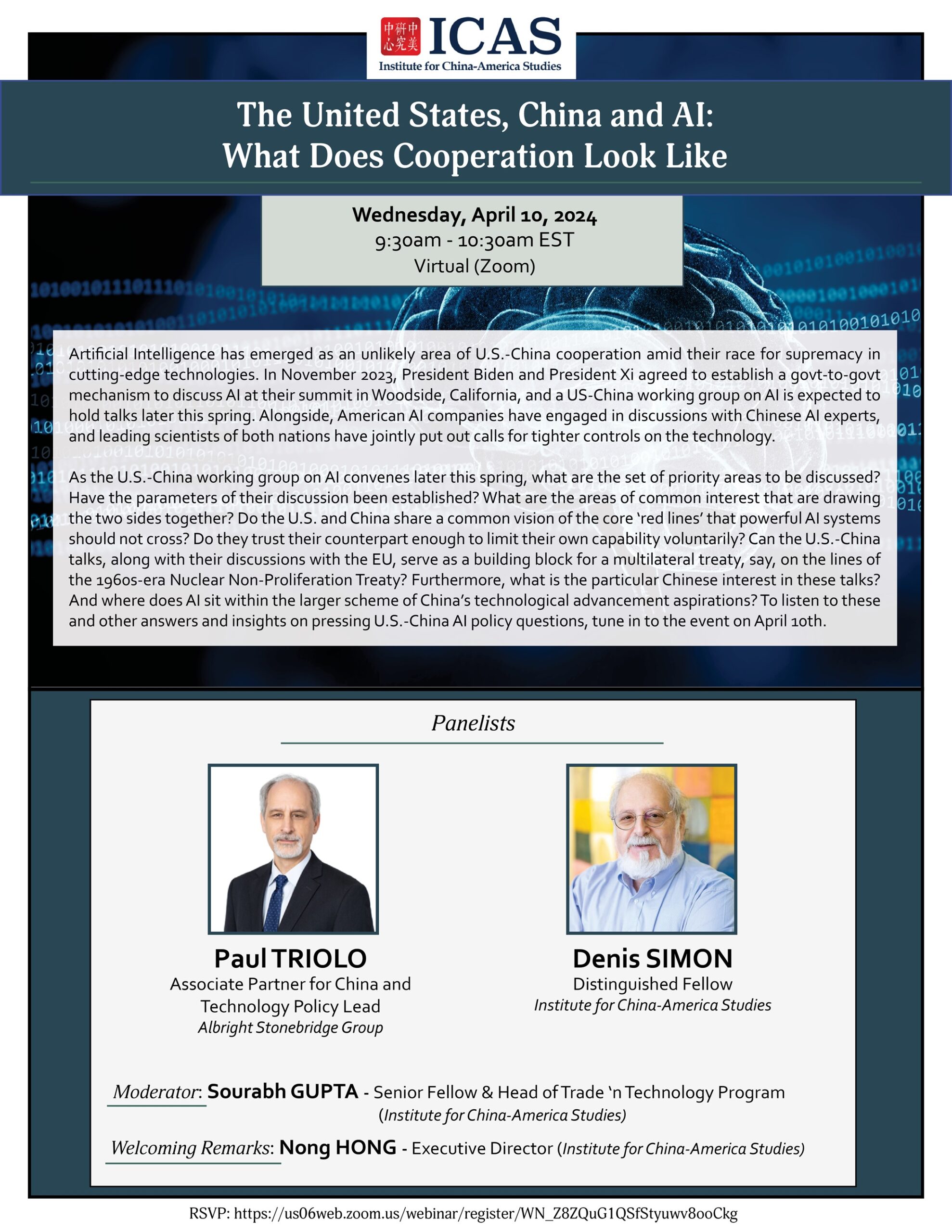

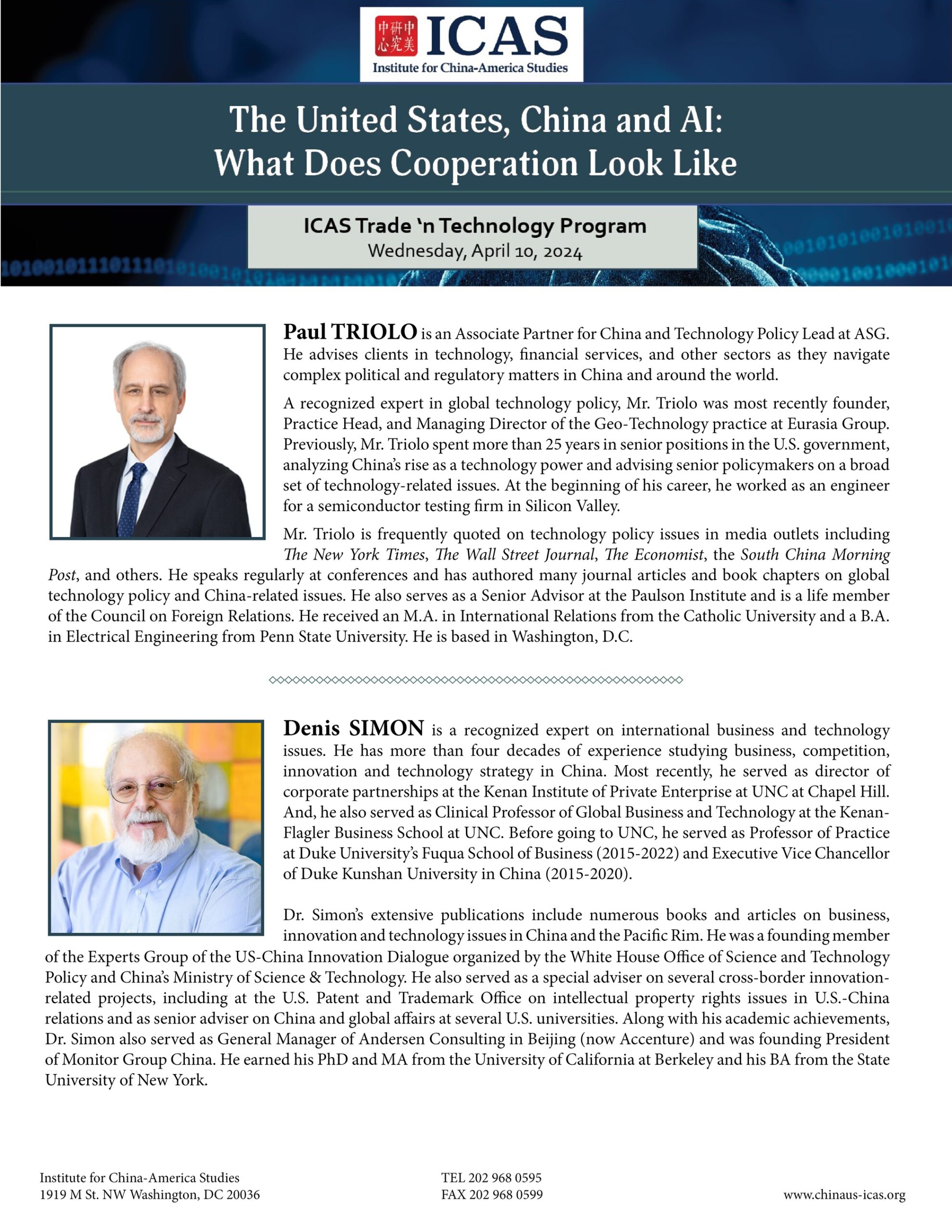

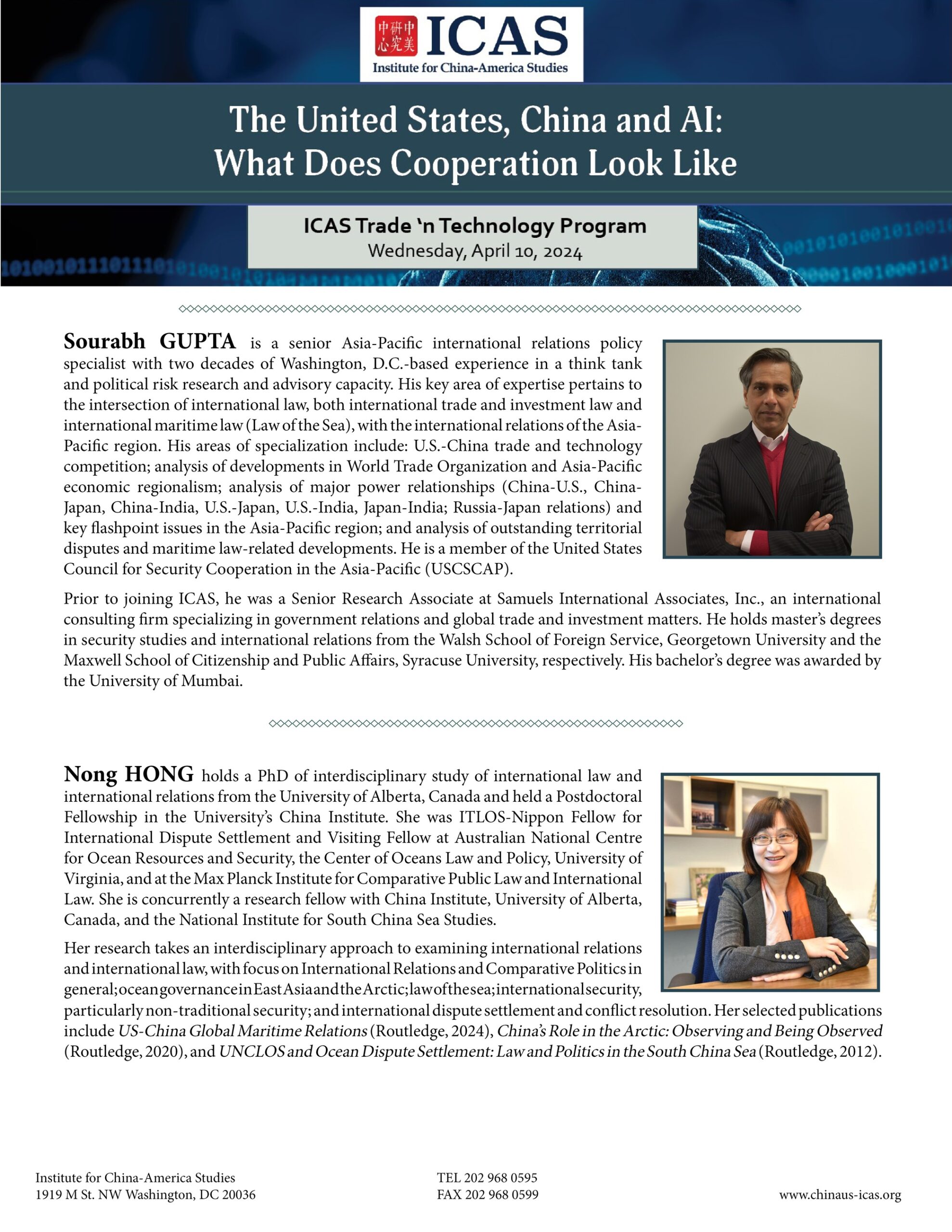

On April 10, 2024, the Institute for China-America Studies (ICAS) hosted a virtual public event to discuss U.S.-China cooperation on Artificial Intelligence (AI) amid their race for supremacy in cutting-edge technologies. The event was titled “The United States, China and AI: What Does Cooperation Look Like” and featured two panelists: Mr. Paul Triolo, Associate Partner for China and Technology Policy Lead at the Albright Stonebridge Group and Dr. Denis Simon, a Distinguished Fellow at the Institute for China-America Studies and a recognized expert on U.S-China science and technology issues. The panelists were introduced by Dr. Hong Nong, Executive Director of ICAS, and the event was moderated by Mr. Sourabh Gupta, Head of ICAS’ Trade n’ Technology Program.

The panelists were of the same view that artificial intelligence (AI), as embodied particularly in its next-generation form of Generative AI, is a technology of immense transformative potential; it is also a technology that could embody significant harms—be it in the sphere of disinformation, cybersecurity, or in terms of military applications. Generative AI, including text-based large language models (LLMs), are still in their infancy. Trained as Generative AI models are on learning underlying patterns within sets of data to generate novel interpretations of existing data, its potential to exponentially transform business processes and output will be realized once it is more fully embodied in and across economy-wide industrial applications. Whoever leads in Generative AI will also enjoy a transformative commercial or economic advantage.

In the panelists’ view, both the United States and China are very aware of the upside advantages and downside risks of Generative AI. As a homegrown innovation, the United States is determined to consolidate and widen its lead on AI’s underlying software and hardware dimensions. Just as importantly, it has preemptively moved out to chart out the regulatory architecture for this technology (via President Biden’s expansive October 2023 Executive Order), having been slow to address the earlier harms of social media or adequately restrain the monopolistic tendencies of Big Tech. For its part, China, having missed the bus on the first three industrial revolutions (mechanization and steam power; mass assembly line production; automation and computer-generated efficiencies), it is determined to ride this revolutionary breakthrough from the ground level up. As the technological boundaries between the physical, digital, and biological worlds both blurs, and this blurring is accelerated by Generative AI, Chinese leaders have been vocal in wanting to harness this ‘new productive force’ to transform itself from a follower to a leader in technology development. Looking at the global landscape beyond the U.S. and China though, there is a huge drop-off in investments and capabilities. As such, if global rules on Generative AI are to be written, it must necessarily involve both the United States and China as well as U.S. and Chinese companies.

The differential head-starts on AI and approaches to regulation goes to the heart of the dilemma regarding the structuring of U.S.-China cooperation on AI. For Washington, the primary focus is the management of the development of frontier AI models, high-risk ones particularly—be in terms of their responsible military use, control over nefarious cyber and other uses, or even in terms of defining the norms and values that should be associated with AI. While (likely) not averse to discussing responsible military use (although this is not a certainty) or control over nefarious uses, China would on the other hand prefer the bilateral conversation be focused on the cooperative development of AI. Between these two approaches lies a significant conceptual gap.

Contrary to Beijing’s desire, the U.S. seeks no cooperation or exchanges on the underlying technological hardware that drive frontier AI models. To the contrary, the Biden administration has placed onerous export control restrictions on leading-edge GPU’s (graphics processing units) to prevent China from training its frontier models. And at the landmark Bletchley Park AI summit last November where China was one among two dozen-odd countries represented, the U.S. ensured that Chinese companies were excluded from the testing of frontier models at the AI safety institutes set up by the United States and the United Kingdom. This begs the question as to how risks, standards and regulations on frontier models can be congruently evaluated and established. On responsible military use, neither side as of yet deploys frontier AI models to guide critical military operations-related applications. This begs the question as to who should even represent either side at the discussion table. As an aside, the impression within the Beltway that the United States and China are gearing up for an epic AI-ordained war is more a function of its morbid fascination with U.S.-China great power rivalry, particularly over an imagined Taiwan conflict, than necessarily a reflection of the state of the militaries’ use and deployment of the autonomous pattern recognition attributes inherent to frontier AI models. And as for a discussion of the norms and values associated with AI, the two sides enter the fray with divergent priorities: for the United States, it is to democratize usage of the technology and counter ills such as elections-related disinformation; for China, it is to enforce macro controls including censorship-related ones, while facilitating the commercial and business-to-business efflorescence and use of the technology.

In conclusion, then, the operative question that ought to be asked therefore is not ‘what does U.S.-China cooperation on AI look like?’ Rather, at least at this point of time, it should be: ‘how do the United States and China get to the point of cooperating on AI?’