Event Summary

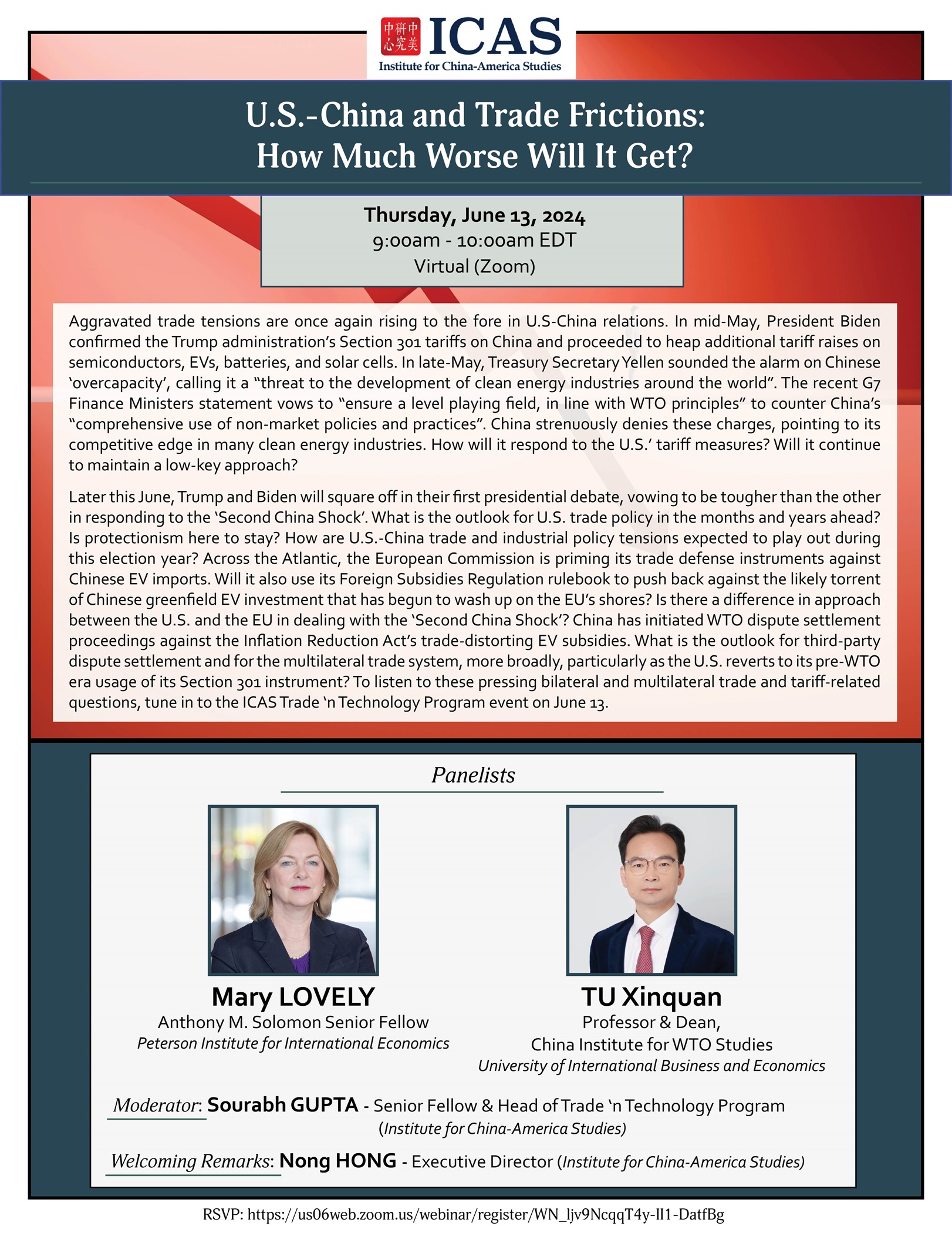

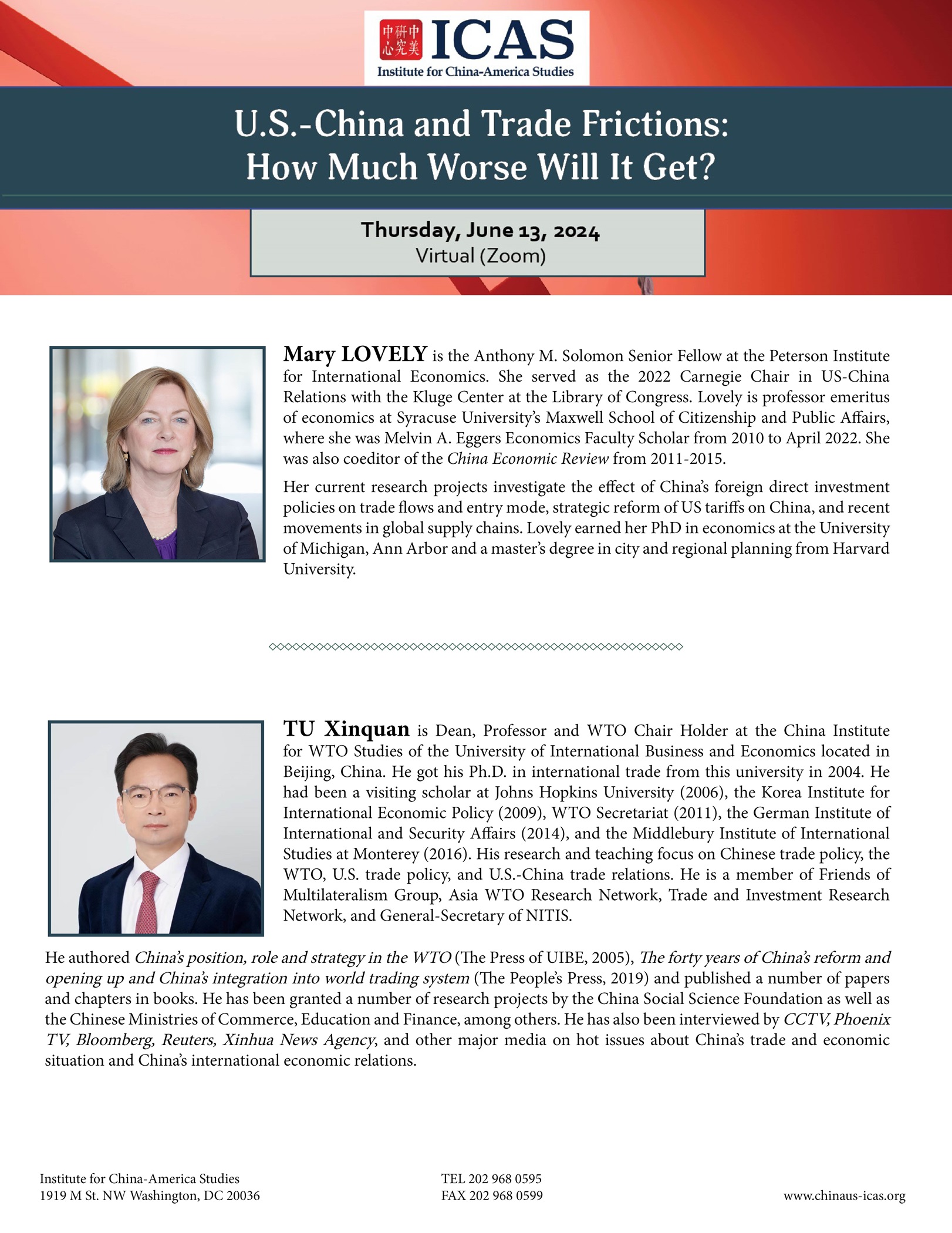

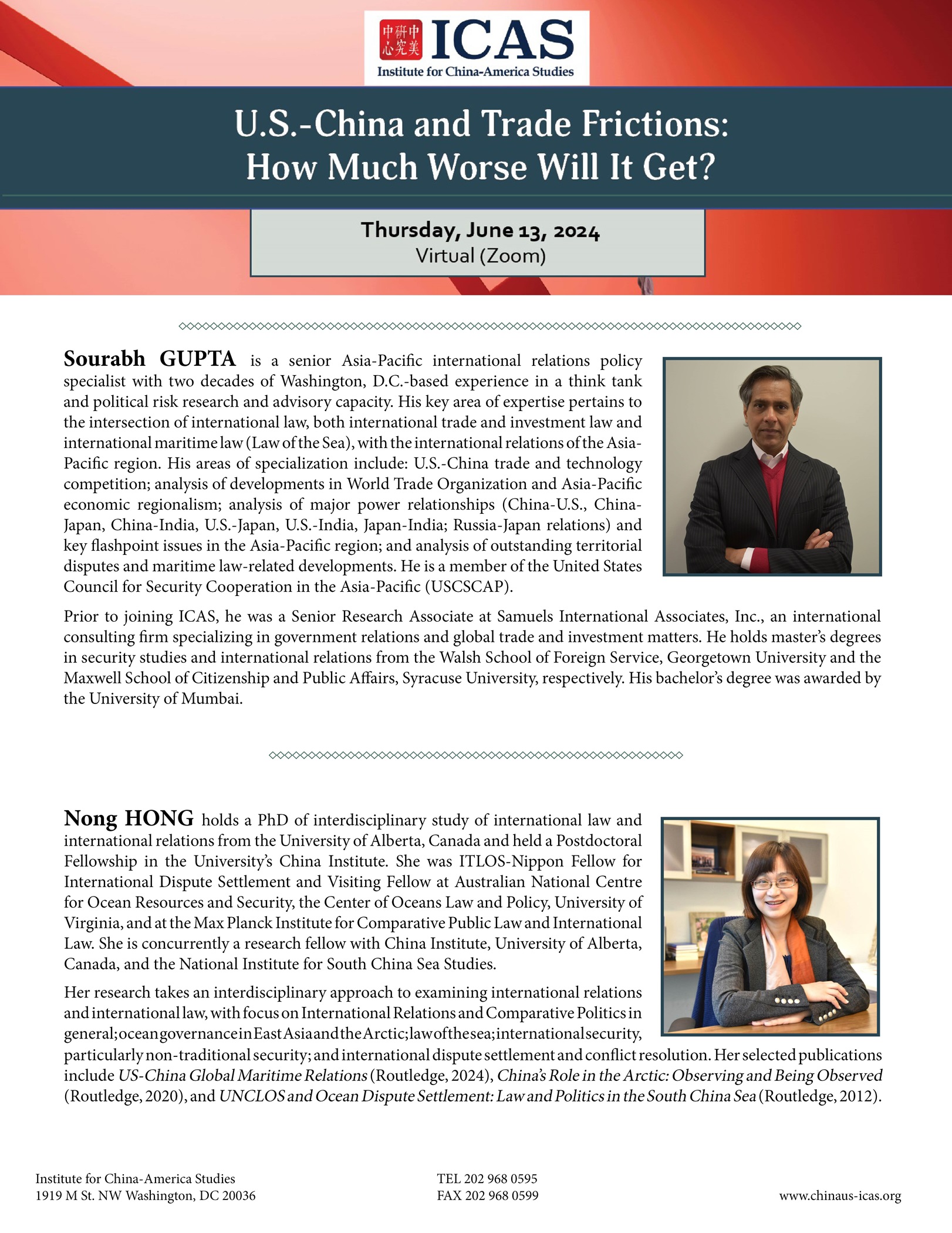

On June 13, 2024, the Institute for China-America Studies (ICAS) hosted a virtual public event to discuss the aggravated trade tensions that have once again risen to the fore in U.S.-China relations. The event was titled “U.S.-China and Trade Frictions: How Much Worse Will It Get?” and featured two panelists: Dr. Mary Lovely, Anthony M. Solomon Senior Fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) and Dr. Tu Xinquan, Professor and Dean at the University of International Business and Economics’ China Institute for WTO Studies. The panelists were introduced by Dr. Hong Nong, Executive Director of ICAS, and the event was moderated by Mr. Sourabh Gupta, Head of ICAS’ Trade n’ Technology (TnT) Program.

The panelists touched on the many drivers and concerns that have coalesced and led to the trade frictions between the United States and China, as well as the many parallels between the U.S.’ earlier altercation with Japan from the 1970s to the early-1990s. For the Biden administration today, China’s high savings rate and excess capacity that reflect a lack of sufficient consumption demand at home, and is manifested in large external surpluses, goes to the nub of the United States’ bilateral trade deficit with China. Beijing’s surpluses are compounded by a variety of unfair trade practices as well as non-market-based subsidies and other trade-distorting industrial policies. On the other hand, in Beijing’s view, the key driver of the United States’ trade (and technology) policy treatment of China as the ‘new Japan’ is its fear that Beijing is not just keen to acquire leadership in key strategic industries but that it will in fact successfully break through the technology barriers being set by Washington in conjunction with its allies. As such, Washington is today trying to slow down China’s progress in a number of advanced manufacturing and clean energy industries, including via the rollout of its own large trade-distorting subsidies. Both sides would be better off instead negotiating a new set of rules on industrial subsidies and competition policy under a multilateral umbrella. If negotiated fairly and inclusively, it was the view of the Chinese side that Beijing would join the consensus. Besides, as noted by both panelists, given the size and persistence of China’s footprint in the trade policy arena, any U.S. approach or vision of a reformed trading order must necessarily include China. There is no other way around this necessity.

Be that as it may, there are three bleak U.S.-China trade and technology policy realities that are here to stay for both the time being and beyond. First, is the growing securitization of both economies and the elevation of national security concerns within their economic relationship. Washington’s ‘small yard’ (of tech controls) will almost certainly get bigger. Second, the tariff instrument is here to stay. Washington’s huge bundle of Section 301 tariffs will remain in place for quite some time; in fact, if Mr. Trump is returned to the White House, the use and abuse of tariffs will be ratcheted up noticeably. Finally, the Biden administration’s framework of reshoring, nearshoring and friendshoring supply chains away from China will be reinforced, creating dilemmas—and opportunities—for third countries caught in the crossfire. Beijing is highly unlikely to bow to U.S. pressuring, however. Non-economic considerations will be prioritized, even if they result in economic disadvantages to China. The essence of the dilemma for both parties, going forward, is to accept that deviation from WTO rules is going to willy-nilly happen, that both sides should exercise a degree of pragmatism when dealing with the other, and that they should preferably frame the terms of their competition on fair and healthy lines. Let U.S.-China trade and technology competition “resemble a marathon rather than a boxing match,” it was counseled.