By Han Guo and Zhan Zhou

China Expected to Work with Europe to Preserve Iran Nuclear Deal after Trump Threat

Kristin Huang

South China Morning Post, October 16

North Korea Rejects Diplomacy for Now

Will Ripley, Zachary Cohen, and Richard Roth

CNN, October 17

Statement from the Press Secretary on President Donald J. Trump’s Upcoming Travel to Asia

The White House, October 16

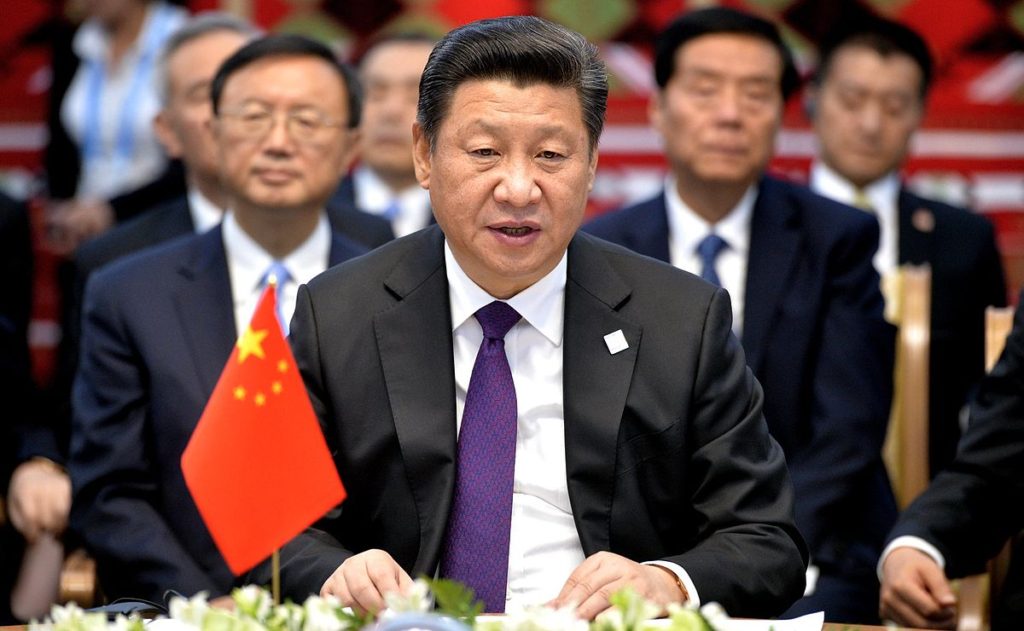

The Communist Party of China held its 19th National Congress in Beijing

Xinhua Staff

Xinhua News, October 18-24

These Seven Man Now Run China

Chris Buckley

The New York Times, October 25

Amid Strained Ties, North Korea Congratulates China on Party Congress

Reuters Staff

Reuters, October 18

China Says Jobless Rate Lowest in Years, but Challenges Persist

Reuters Staff

Reuters, October 21

North Korea Will Not Resume Six Party Talks Without Change in US Policies

Choi He-Suk

Korean Herald, October 22

China and ASEAN to Go Ahead with First Joint Naval Exercise in Sign of Greater Engagement

Sarah Zheng

South China Morning Post, October 24

Trump to Skip Key Asia Summit in Philippines to Go Home Earlier

Josh Rogin

The Washington Post, October 24

Why Do We Keep Writing about Chinese Politics As if We Know More Than We Do?

Jessica Batke and Oliver Melton

China File, October 16

“In the light of China’s 19th Party Congress, western media and think tanks have published numerous articles and analysis deciphering Chinese politics. But because China guards information about its internal affairs so closely, it is particularly challenging to get the facts straight. Most analysts simply lack sufficient evidence to support their conclusions. It is especially difficult to decipher the power struggle of China’s ruling party, a topic that is favoured by many western observers. This runs the very real risk of misinterpreting what is actually happening in Chinese politics.”

A New Era Dawns for Xi Jinping’s China, But What Will It Mean for the Rest of the World?

David Zweig

South China Morning Post, October 25

“David Zweig says the Communist Party’s goal to build national power follows logically from its earlier focuses on national unity and wealth creation. But a political system that is ideologically driven and in the grip of an almost all-powerful leader could be a recipe for disaster.”

“We have entered the “third era” of the history of the Chinese Communist Party and “New China”. That is the historical construct that Xi Jinping and the party have presented as a way to understand the 19th party congress and the next 15-30 years of China’s development.”

Russia Steps Up as Go-between on North Korea

Tomoyo Ogawa

Nikkei Asian Review, October 16

“Russia has been setting up a number of high-profile meetings with North Korean officials, positioning itself as an intermediary for negotiations with the isolated state in a bid to improve Moscow’s strained relations with the U.S.”

See also: the latest news on Russia’s latest sanctions against North Korea:

http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-10/17/c_136684459.htm

Why Trump’s Threat to Withdraw from the Iran Nuclear Deal is a Concern for China

Sarah Zheng

South China Morning Post, October 17

“China is calling on the United States to preserve the Iran nuclear deal reached in 2015, after US President Donald Trump slapped new sanctions on the nation while threatening to tear up the agreement.”

“In a speech on Friday, Trump refused to certify the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, accusing Tehran of committing “multiple violations” of the deal despite international inspectors saying it had complied with it.”

What Did the CCP Party Congress Mean for China’s Diplomats?

Ricardo Barrios

The Diplomat, October 30

“In a speech on Friday, Trump refused to certify the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, accusing Tehran of committing “multiple violations” of the deal despite international inspectors saying it had complied with it.”

New Approaches to the South China Sea Conflicts

Conference hosted by University of Oxford, October 19-20

Dr. Nong Hong, the Executive Director of ICAS, attended a two-day conference at the University of Oxford focused on identifying viable policy solutions to the many disputes in the South China Sea. All of the main claimants, including China, the Philippines, Vietnam, Taiwan, Malaysia and Brunei, have ratified UNCLOS (The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea). UNCLOS contains specific mechanisms for dispute resolution, but these have not yet proven to be effective. Furthermore, as evidenced by China’s decision not to participate in the recent arbitration case brought by the Philippines or to accept the decision of the tribunal, it is unclear whether UNCLOS (or international agreements like it) can be a productive tool for managing this conflict. Dr. Hong gave a presentation at the conference on the topic, “Lawfare Surrounding the South China Sea: The Role of UNCLOS.” Dr. Hong also gave a speech at the public forum following the conference entitled, “New Approaches to the South China Sea Conflicts.”

Maritime Security and Cooperation: Opportunities and Challenges in the Asia-Pacific and the Arctic

Conference co-hosted by ICAS and the China Institute, University of Alberta, October 26-27

ICAS sent a delegation led by Executive Director Dr. Nong Hong to Edmonton, Canada to attend the co-organized 5th annual Asia Maritime Security Forum, Maritime Security and Cooperation: Opportunities and Challenges in Asia-Pacific and the Arctic.

The two-day forum examined similarities and differences between the maritime security and stability in these two regions. The territorial and sovereign rights disputes in the South China Sea are frequently covered in academia and the media, but more often than not the Arctic is overlooked. This region is increasingly becoming a battleground for competing interests and claims. Thus far, international law and the law of the sea has managed to resolve these issues as they arise, but that will become increasingly difficult. As more of the Arctic becomes accessible and its resources harvestable due to climate change, the frequency and complexity of these competing claims will only increase. Current ambiguity in international law is already proving to be problematic in resolving the disputes in the South China Sea. It is essential that this doesn’t spill over into the Arctic as well.

This conference sought to address these challenges and identify common ground for cooperation and dispute resolution in the South China Sea and the Arctic.

5th International Conference on Economics, Politics, and Security in China and the U.S.A. – “Partnering for the 21th Century”

Conference co-hosted by the School of Public Policy, University of Maryland, and National University of Defense Technology, October 24-25

The School of Public Policy of the University of Maryland and China’s elite National University of Defense Technology jointly hosted an international conference last week featuring panels on U.S.-China bilateral relations, nuclear security issues, cybersecurity in the 21th Century, and security in the Pacific.

ICAS research associate, Will Saetren, participated in the 5th panel on Security in the Pacific. He highlighted the challenges both the United States and China are facing in the South China Sea. Solving the issues requires a long-term commitment to crisis management and to reconcile Chinese and international laws. Importantly, both countries need to agree to strengthen crisis management mechanisms to prevent misunderstandings and disastrous escalation.

Xi Takes Charge: China’s Political Landscape after the 19th Party Congress”

Event hosted by the University of California Washington Center and the US-Asia Institute, October 23

“The upcoming 19th Party Congress in China, considered to be President Xi Jinping’s ‘midterm,’ is fraught with risks and challenges for him. As Xi seeks to strengthen his hand by elevating his close supporters into the Politburo and its Standing Committee, the Party’s institutional rules and precedents require him to share power and patronage with other senior leaders.”

This event addressed the following questions: Will Xi follow the rules and preside over a normal collective process or will he flout the rules in order to consolidate his position as the core leader? What is the agenda for economic policy reform?

Featured Event: U.S-Asia and U.S.-China relations in the wake of Donald Trump’s Trip to the Asia-Pacific

Roundtable discussion hosted by ICAS, November 16

New Team, New Agenda? What the 19th Party Congress Tells Us

Event hosted by The Brookings Institute, November 2

China’s 19th Party Congress: Implications for China and the United States

Event hosted by Kissinger Institute on China and the United States, November 3

The Dawn of a New Era: Readout of the 19th Party Congress

Event hosted by Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 3

America’s Asia-Pacific Alliances In a Time of Uncertainty and a Rising China

Event hosted by The Paulson Institute and Harris Public Policy, November 3

China’s Power: Up for Debate – The Second ChinaPower Annual Conference

Event hosted by Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 14

Managing Strategic Competition in Asia

Event hosted by The National Bureau of Asian Research, November 15

By Han Guo and Zhan Zhou

China, one of the world’s most influential powers, held its most significant political meeting last week. The 19th CPC National Congress marks a milestone in the country’s development as the new ruling guideline of the party, “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era,” was written into the Party Constitution. The new Constitution places emphasis on building “the community of shared future for mankind” and addresses President Xi’s “Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).” They are the most notable diplomatic achievements of China in the past five years.

Prior to this, the Party Constitution has had no comprehensively renewal of the section on foreign policy for twenty years. In that light, what is the significance of those two strategic proposals, what has been achieved so far, and what can we expect in the future?

Building “the community of shared future for mankind” is a significant international strategy proposed by President Xi. Despite global economic growth, the past five years witnessed political instability as economic isolationism, political separatism and terrorism were on the rise. In the context of globalization, those issues challenge all of us. How should we as human beings think of our future and the future that lies ahead of us? As an answer to those profound questions, “the community of shared future” is a timely response that provides a much-needed account for the outlook of the integrating globe. It points out that the future of mankind is essentially dependent on each other, and this dependence requires the communal effort of every country on the planet. To establish this community, President Xi has issued a call to “make sure that all countries respect one another and treat each other as equals… seek win-win cooperation and common development… pursue common, comprehensive, cooperative and sustainable security… and ensure inclusiveness and mutual learning among civilizations.”

BRI, also known as “the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road,” is a crucial step towards realizing the community of shared future for mankind, and probably the most ambitious strategy China has ever launched, which is slated to provide much-needed infrastructure development and financial coordination for the 65 Eurasian and African countries involved. The initiative aims at promoting the connectivity and cooperation between those countries. As of the end of 2016, China has reportedly invested more than $50 billion in its BRI partners, and the total volume of trade between China and other BRI countries has exceeded $3 trillion. Chinese firms have also established more than 50 economic and trade zones in more than 20 countries.

To secure the enormous amount of investment needed for the project, China has proposed to found the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), established the Silk Road Fund (SRF), and invested in the Silk Road International Bank in Djibouti. Like BRI, AIIB is widely supported by the international community as the bank currently has 56 member states with capital investments exceeding $100 billion. For perspective, that is equivalent to roughly half of the capital possessed by World Bank. According to PhoenixTV, AIIB has provided $1.7 billion in loans for 9 BRI countries, and SRF has invested $4 billion.

Huge investment have led to rapid and successful implementation of the first BRI projects. The first physical platform of the Silk Road Economic Belt, the China-Kazakhstan logistic cooperation base, was opened in May of 2014. Several cross-continental rail lines went into operation until the beginning of 2017, including the Yiwu-London rail line, the Addis Ababa-Djibouti electrified rail line, and the Lanzhou-Minsk rail line. Other infrastructure projects, including the Belgrade-Budapest high-speed railway and the Moscow-Kazan railway, are currently under construction.

In lieu of these achievements, the 19th CPC National Congress enshrined “community of shared future” and BRI into the Party Constitution, which has profound implications for China’s diplomacy under President Xi Jinping. It is a step that legitimizes the ideas and practices behind the two initiatives. It also sends a powerful signal to the world about the credibility of China’s policy consistency, at a time when the United States is demonstrating anything but. Finally, the two enshrined initiatives lay the groundwork for what will come as China’s diplomacy in the “New Era,” whose characteristics are manifested in four perspectives.

Perspective one, China has started its transition from a “big nation” (大国) to a “strong nation” (强国). Its foreign policy guidelines have clearly shifted from the “keep a low profile and bide one’s time” of the past (韬光养晦), to “strive for achievements” (奋发有为). This will likely translate to a far more assertive Chinese foreign policy in the near future. It also means that China will have to assume a much larger mantle of responsibility both domestically and globally. China’s recent economic growth has been unprecedented. In 2016 Chinese foreign investment amounted to $175 billion, twice the size that it was in 2012. China has also become the world’s largest export economy, and is set to surpass the United States by 2029 in terms of nominal GDP. The expansion of Chinese interests overseas will mean that the government has to bolster its efforts to safeguard its citizens and investments, which will in turn lead to a need for greater political representation. Given the power vacuum created by the lack of foreign policy vision of the Trump administration, this transition is almost inevitable.

Perspective two, a Chinese concept of “community of shared destiny” is needed to tackle the perils of current global political system. Countries around the world now face common threats from climate change to global economic recessions. President Xi said “no country alone can address the many challenges facing mankind… nor retreat into self-isolation.” Admittedly, previous globalization and the flow of capital have deepened inequality and exacerbated exclusive development, but President Xi offered a dual-track solution to these problems. Although he emphasized his commitment to “supporting multilateral trade institutions,” he also pledged to “increase aid to the least developed countries” and “expand the representations and voices of developing countries in international affairs.” These remarks suggest that China will heed its actions to avoid the old model of colonialism while promoting convergence of mutual interests and responsibility, through which a “community of shared future” can be forged.

Perspective three, China’s development of the past 30 years bears notable differences from the Western model commonly dubbed as the “Washington Consensus,” including democratization, free market and privatization of state-owned enterprises. The key to China’s economic success boils down to the combination of the market and state (with the state playing a crucial role), the merit-based selection of bureaucracy and the overarching emphasis on political stability. These offered a “Chinese approach” to “countries and nations who want to sprayed up their development while preserving independence.” The “Chinese wisdoms” provide a philosophical guideline on incorporating development theory (in China’s case, Marxism) with the country’s socio-economic conditions. As President Xi noted, “a political system cannot be judged in abstraction without regard for its social and political context, its history and its cultural traditions.” This implies that China’s political systems are never thought of as “universal,” nor as “imitating the China model an indispensable part of the justice.” Hence the concerns over China “selling” the so-called “China Model” are unwarranted. Empirically, China upholds its longstanding policy of non-interference. Its foreign aid has never included terms to suppress the political-economic systems to the recipient states. China no longer sees benefits from ideological expansions, nor does it have the wherewithal to promulgate Chinese systems the way Soviet Union promoted communism.

Perspective four, the elevated status of diplomatic personnel in decision-making body signals an improvement of inter-agency coordination and coherence. One of the most notable personnel changes made the Party Congress was the promotion of State Councilor Yang Jiechi to the Politburo. Traditionally, the Foreign Minister and the State Councilor are located in the Central Committee, while their uniformed counterparts (vice chairman of the Central Military Commission) almost always hold the seats in the Politburo. In the past, this has led to the sidelining of the Foreign Ministry institutionally, and severely weakened its ability to influence China’s top leadership. There are plenty of examples where the rhetoric of the Foreign Ministry have failed to match up with the policies pursued by hawkish elements of the government. In an interview with the BBC, Zeng Jinghan explained how the Foreign Ministry had a hard time in “coordinating actions by local governments, the military, and state-owned petroleum enterprises during the South China Sea fray.” Xi’s moves to strengthen the Foreign Ministry will undoubtedly provide a more unified and authoritative channel to represent the official policy of the government as China seeks to play a greater role on the global stage.

The 19th CPC National Congress underscored a degree of continuity in China’s foreign and domestic policies. More importantly, it set the stage for China to assume a global leadership role and fill the vacuum left by the United States as it retreats into isolationism. In an era with uncertainties and opportunities, China now stands at a crucial crossroad. It must decide if it will pursue the methodology and mindset of a traditional rising power, squandering its power prioritizing self-interests above all else, or that of a responsible stakeholder, contributing positively to the global order and progress of mankind. The world expects the latter.

Han Guo and Zhan Zhou are research assistants at the Institute for China-America Studies.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2025 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.