By Sourabh Gupta

Yi Gang named head of People’s Bank of China

BBC News, March 19

Liu He: China’s quiet economist becomes top economic leader

Sarah Porter

BBC News, March 19

Trump’s Killing of Chip Deal Pushes Protectionism as It Invokes Security

Ana Swanson, Cecilia Kang, Alan Rappeport

The New York Times, March 13

China’s Huawei Is at Center of Fight Over 5G’s Future

Raymond Zhong

The New York Times, March 7

Lift-off in space plane race as China tests hypersonic drone model

Stephen Chen

South China Morning Post, March 6

Key takeaways from Chinese Premier Li Keqiang’s opening speech for the National People’s Congress 2018

Zhou Xin

South China Morning Post, March 5

China pledges friendship with Taiwan amid tensions over U.S. bill

Ben Blanchard

Reuters, March 3

The Dirty Secret of American Nuclear Arms in Korea

Walter Pincus

The New York Times, March 19

“As President Trump prepares for a possible meeting with Kim Jong-un, the North Korean leader, many Americans are raising warnings that North Korea has walked away from previous arms agreements. But those skeptics should remember that it was the United States, in 1958, that broke the 1953 Korean Armistice Agreement, when the Eisenhower administration sent the first atomic weapons into South Korea.”

For China, One Of The Greatest Risks Of Trump-Kim Talks Is Being Sidelined

Bonnie Glaser

NPR, March 12

“Chinese President Xi Jinping is undoubtedly relieved that the danger of war on China’s doorstep that could threaten Chinese security and undermine his national rejuvenation plan has decreased. Beijing worries, however, that it will be marginalized from the diplomatic process that may soon get underway, making it difficult to ensure that Chinese national interests are protected.”

“If new negotiations are launched, China may not have a seat at the table and that prospect is creating anxiety. Although the Chinese have long insisted that the crux of the North Korea nuclear issue is a dispute between Washington and Pyongyang, they want to continue to exert influence over major policy decisions, and fear that a U.S.-North Korea deal could have negative implications for Chinese geopolitical interests.”

“If China is excluded for the time being, the Trump administration would be wise to keep Beijing in the loop. Even in the best-case scenario, negotiations are likely to be protracted. Sustaining maximum pressure on North Korea through sanctions, which was likely a factor in Kim’s outreach to Seoul and his offer to meet with Trump, will require continued Chinese cooperation.”

How China Is Challenging American Dominance in Asia

Max Fisher, Audrey Carlsen

The New York Times, March 9

“As China grows more powerful, it is displacing decades-old American preeminence in parts of Asia. The outlines of the rivalry are defining the future of the continent. We asked a panel of experts how they think the power has shifted in the past five years:”

Trump Has Agreed to Meet North Korea’s Kim Jong Un. Now What?

David Tweed

Bloomberg, March 9

“U.S. President Donald Trump has stunned the world by agreeing to meet North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, a man he’s ridiculed as ‘Little Rocket Man’ and whose regime only months ago he threatened with ‘fire and fury.'”

Is North Korea’s offer to halt nuclear and missile tests too good to be true?

South China Morning Post, March 7

“US President Donald Trump appears to have got what he wanted from North Korea: a willingness to suspend nuclear testing and a promise to put its entire arsenal of atomic weapons on the negotiating table. But is it too goot to be true?”

China Is Making a Bold Military Power Play

David Tweed, Adrian Leung

Bloomberg, March 6

“As lawmakers meet this week to cement Xi Jinping’s power at home, China’s president is also looking to boost his country’s military might abroad. He’s overhauled China’s military to challenge U.S. supremacy in the Indo-Pacific, most visibly with a plan to put half-a-dozen aircraft carriers in the world’s oceans. Still, Xi has a problem: He needs bases around the world to refuel and repair his global fleet. So far, China only has one overseas military base, compared with dozens for the U.S., which also has hundreds of smaller installations.”

Washington Must Own Up to Superpower Competition with China

Will Saetren, Hunter Marston

The Diplomat, March 8

“The first step is for the U.S. to admit that China is a full-blown superpower.”

US tailors forces to deter growing Chinese nuclear threat

Bill Gertz

Asia Times, March 5

“Chinese secrecy about its nuclear forces and their use was a major theme of the Pentagon’s recently completed Nuclear Posture Review that outlined a new ‘tailored deterrence’ policy for China.”

China’s Rapid Rise as a Green Finance Champion

Event hosted by Woodrow Wilson Center, March 5

“The Year of the Dog marks China’s fourth year in its “war on pollution” and the central government continues to ramp up laws and regulations to reverse damage to the country’s air, water, and soil. To build Xi Jinping’s ecological civilization, China will need to invest nearly 3-4 trillion RMB each year to improve pollution enforcement and expand pollution control, clean energy, and energy efficiency industries. Building on the country’s already large green development investments, the Chinese government created five Green Finance Pilot Zones in 2017 to help banks develop new tools for green lending, green insurance, and green equities to fund the green economy. Additionally, two years ago, China launched a green bond market that is now the second largest in the world. At this March 5th meeting, CEF is bringing in three experts to delve into the financial and environmental opportunities and risks as China moves into this new era of green financing.”

Watch the webcast here.

U.S. Trade Policy in Northeast Asia

Event hosted by Woodrow Wilson Center, March 6

This panel featured three speakers who examined the consequences of U.S. bilateral trade policies toward Northeast Asia one year into the Trump administration. TJ Pempel, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, spoke first on how Trump has upended the existing global liberal order that has largely defined U.S. economic and foreign policy by adopting domestic protectionism and economic nationalism; the consequences include loss of U.S. credibility in Asia and the global order moving on with without U.S. presence. Takashi Terada, a professor at Doshisha University, spoke specifically on Japanese economic policy and U.S.-Japan relations. Japan has strategically postured itself by being involved in regional agreements–TPP-11 and RCEP–and fostering high-level economic dialogue with the U.S. in their bilateral relationship. Yul Sohn, a professor at Yonsei University, spoke on South Korea’s economic policy challenges, particularly with China and the U.S., its two largest trading partners. A U.S.-China trade war will inevitably hurt Korea; KORUS negotiations will not mitigate the harm of U.S.-China spillover; and strengthening Korea-Japan relations is strategically the best option for Korea.

The Return of Marco Polo’s World

Event hosted by Center for Strategic and International Studies, March 9

“As Europe disappears, Asia coheres. The supercontinent is becoming one fluid, comprehensible unit of trade and conflict, as the Westphalian system of states weakens and older, imperial legacies – Russian, Chinese, Iranian, Turkish – become paramount. Watch the Simon Chair’s Reconnecting Asia Project in conversation with Robert D. Kaplan about his new book, The Return of Marco Polo’s World: War, Strategy, and American Interests in the Twenty-first Century, to discuss how Eurasia’s coherence impacts the U.S. ability to influence the power balance in Eurasia.”

Watch the webcast here.

The Logic of American Nuclear Strategy

Event hosted by Center for Strategic and International Studies, March 9

“Join the Missile Defense Project for a conversation with Dr. Matthew Kroenig on his new book, The Logic of American Nuclear Strategy (2018). The discussion will address U.S. nuclear strategy, force structure, history, and debates.”

Watch the webcast here.

Report Launch: China’s Interests in the Arctic: Opportunities and Challenges

Event hosted by Institute for China-America Studies, March 16

The Institute for China-America Studies launched its latest report on China’s interests in the Arctic, authored by Executive Director, Dr. Nong Hong. In a panel discussion featuring Sherri Goodman, Senior Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, moderated by Gordon Houlden, Director of the China Institute at the University of Alberta, Dr. Hong presented her findings and discussed the implications of China’s newly released Arctic policy white paper.

A large portion of the discussion focused on China’s “science diplomacy” approach to the Arctic and its self-characterization as an “important stakeholder” in the region. The panel also discussed the strategic implications of further development of the Arctic—and potential cooperation—in the region.

Summary of the report launch here.

U.S. Policy Towards China: A Conversation with Senator Ted Cruz

Event hosted by Council on Foreign Relations, March 21

One Belt One Road, and Many Power Plants: Linking China’s Domestic and Global Energy Ambitions

Event hosted by Woodrow Wilson Center, March 22

Book Launch: China Steps Out: Beijing’s Major Power Engagement with the Developing World

Event hosted by Center for Strategic and International Studies, March 22

China at War

Event hosted by Woodrow Wilson Center, March 26

By Sourabh Gupta

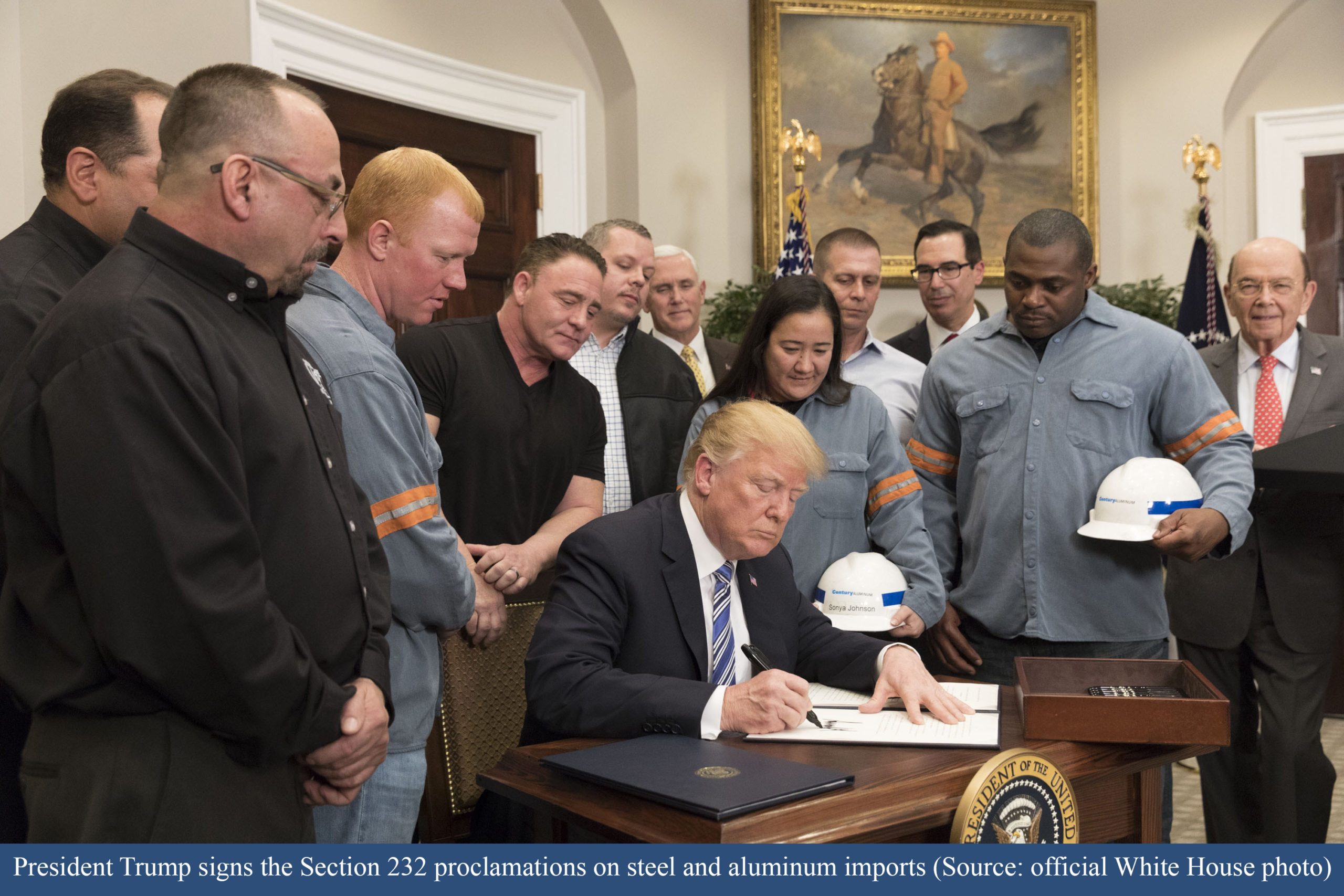

In his seven-point economic plan to “Make America Great Again,” candidate Donald Trump promised to “use every lawful presidential power to remedy trade disputes if China [did] not stop its illegal activities, including its theft of American trade secrets.” To this end, he enumerated an unusually detailed list of statutory and unconventional trade policy enforcement tools—Section 232 of the Trade Act of 1962; Section 201 and Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974—with which he would punitively sanction China.

On March 8, 2018, President Donald Trump began translating words into deeds by issuing a tariff proclamation under Section 232 to restrain the imports of steel into the United States with the intent to counter trade practices which, in his view, were undermining U.S. national security. The Section 232 measure is a highly unconventional and controversial way to restrict imports on the basis of their detrimental impact on U.S. national security. Its employment against foreign trade partners, particularly China, is likely to be the first volley in an increasingly torrid summer of lethal trade pyrotechnics.

As per the proclamation, a 25 percent tariff is to be imposed on a range of ‘steel articles’ imports starting March 23, 2018. The core purpose of the measure is to “help [the U.S.] domestic steel industry to revive idled facilities, open closed mills, preserve necessary skills by hiring new steel workers, and increase production, which will reduce [the United States’] need to rely on foreign producers for steel and ensure that domestic producers can continue to supply all the steel necessary for critical industries and national defense.” Achieving long-term economic viability of the domestic steel industry is assessed as restoring capacity utilization to an 80 percent rate; the industry currently operates overall in the 72-74 percent range.

The 25 percent tariff will be imposed on all countries—friend and foe alike—with the exception of Canada and Mexico, at least for the time being. With these two countries, discussions are to continue to find a way forward to limit their steel exports to the United States without the immediate imposition of the tariff. Canada and Mexico were the no. one and no. four steel exporters to the United States in 2017, and together accounted for a quarter of U.S. steel imports in 2017.

As a form of reassurance to other allies and partners with whom the United States has a security relationship, the Trump administration registered its openness to “discuss alternate ways to address the threatened impairment” to U.S. national security caused by their steel exports. Five U.S. allies feature in the top 10 list of steel exporters, and Australia currently heads the list of countries working with the administration to avoid the imposition of Section 232 tariffs. Australia is also a trading partner with whom the United States enjoys a trade surplus—an indispensable metric in the Trump administration’s eyes.

There are a number of key takeaways stemming from the Section 232 measure, none of which are appealing or exalting.

First, in his fifteen months in office, Trump has shown that his pronouncements deserve to be taken both literally and seriously. The Section 232 steel tariffs is just the latest case in a number of unorthodox campaign pledges—from the Paris climate deal to the Iran nuclear agreement to the rejection of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement—that have been translated into action.

Second, contrary to the administration’s assertions about the potential threat to national security from steel imports, the purpose of the tariff is solely to protect, and thereby restore, the economic viability of the domestic industry. The steel requirement of the Defense Department is modest and U.S. domestic steel production (although not employment or profit margins) has been remarkably stable over the past two decades. The tariff measure is a classic case of textbook protectionism masquerading as national security to support a politically-connected sunset industry.

Third, ‘banking on protectionism’ is a tried-and-tested operating model of the chief architect of the Section 232 steel measure, U.S. Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross. In the early-2000s, Ross used President George W. Bush’s temporary safeguards on steel (that lasted from 2002 to late-2003) to purchase uncompetitive mills, which he then turned around with the cooperation of the industry’s powerful unions for a handsome profit.

Fourth, the 25 percent tariff rate will almost-certainly have to be raised in the near future. The amount of the tariff was designed on the basis of a global back-calculation to ensure an 80 percent capacity utilization rate (at 2017 demand levels plus exports) within the domestic industry. With Canada and Mexico—accounting for a quarter of global exports—to be exempted, the tariff on the rest of the world will need to raised to condense the rest of the world’s quota within the projected reduction envelope (to ensure 80 percent domestic capacity utilization). This type of de facto ‘managed trade’ targeting, as is the case with this tariff imposition, has no place in the post-World Trade Organization (WTO) global trading system.

Fifth, global trade law includes a national security exception clause (GATT Article XXI Security Exceptions) that permits a country to depart from its international trade obligations, including tariff bindings, at a time of war or other emergency in international relations. However, during a non-international emergency situation, a dispute settlement panel will likely look unfavorably on the United States’ claims if a foreign trading partner files a legal challenge arguing that its legitimate expectations of trade benefits were nullified or impaired by the U.S. action. When the 25 percent tariff measure is challenged within the WTO’s dispute settlement system (as it will), it will be worth noting whether or not the United States cites the national security exemption in its defense. There is no prior jurisprudence on this point, although a national security exemption-related case involving Qatar and the United Arab Emirates is currently being heard within the WTO system.

Finally, the key intended target of the measure, China, is not among the top 10 steel exporters to the United States. Of the almost $30 billion of total steel product imported by the United States in 2017, China exported less than $1 billion worth of such products. All of China’s top 10 steel exports markets are in East, South or Southeast Asia (aside from Saudi Arabia). By the time the 25 percent tariff gets around to penalizing China, it will have inflicted far more damage on other steel exporting countries, including five U.S. treaty allies. The willingness to disregard establishment opinion and impose a highly unconventional and controversial tariff bodes ominously for the results of the ongoing Section 301 investigation of China’s intellectual property rights (IPR). The case to penalize China is stronger (although hardly WTO-proof) and the will to do so in Washington far stronger.

The United States and China have their trade guns locked and loaded, and the first volley has already been fired. The spring and summer of 2018 will likely witness the fiercest trade fighting since since the infamous U.S.-Japan battles of the 1980s. It is no small irony that this trade war is being instigated by the same characters in the United States whose formative experiences were shaped by the bruising battles of the 1980s, and who continue to remain prisoners of that past.

Sourabh Gupta is a Senior Fellow at the Institute for China-America Studies (ICAS) in Washington, D.C.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2025 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.