Image Source: DFC.gov

Research Associate & Program Officer

America’s attitude towards the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has shifted from an initial ambivalence to near total distrust. This shift has spurred new U.S.

The U.S. government has increasingly and aggressively accused China’s BRI of being an influence campaign that ensnares developing countries through ‘debt-trap diplomacy.’ Two U.S. government Acts: the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act (ARIA) of 2018 and the Better Utilization of Investments Leading to Development (BUILD) Act of 2018 are at the heart of America’s pushback against BRI. These Acts have led to the creation of the U.S International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) and the Blue Dot Network.

The DFC is an executive agency that brings together the capabilities of OPIC and USAID’s Development Credit Authority to finance private development projects. The DFC officially replaced OPIC on January 2nd, 2020. The initial spending cap of DFC investments will be $60 billion, doubling OPIC’s $29 billion cap.

The Blue Dot Network is a multi-stakeholder initiative led by the DFC (formerly the U.S. Overseas Private Investment Corporation), Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), and Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC). Although this initiative is in its embryonic stage and lacks a concrete framework as of now, it is advertised as a more sustainable option than BRI by only financing infrastructure projects that are proven to be market-driven, financially viable, and transparent.

On December 20, 2019, President Trump reauthorized the Export-Import Bank of the United States (Ex-Im) through the end of 2026. A major provision under the reauthorization of Ex-Im is the establishment of the Program on China and Transformational Exports. The purpose of the program is to support the extension of loans, guarantees, and insurance that are competitive with the rates and terms extended by China and other covered countries.

Initial reactions to these U.S.-led initiatives from some of its major target recipients, such as the ASEAN countries, have been mixed largely due to the waning of U.S. influence in many of these regions well before the Trump Administration took office. Unless the U.S. proves to recipient countries that it is serious about these initiatives and that the higher quality assurance and transparency standards are worth meeting, it will be difficult for the DFC or Blue Dot Network to compete with the easy loans that China’s BRI investments offer.

In 2016, the Institute for China-America Studies (ICAS) published a report on American sources of concern and areas of possible cooperation on China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). With 2019 having drawn to a close, numerous new BRI projects have been planned, financed, or completed since then. For example, in October 2018, and more recently on October 24, 2019, United States Vice President Mike Pence delivered speeches where he reiterated the Trump Administration’s position that the Belt and Road Initiative is an influence campaign that ensnares developing countries through ‘debt-trap diplomacy.’ What began as American ambivalence has evolved into an outright distrust of China’s intentions and a desire to compete against BRI. As such, it is important to revisit new developments in this area of U.S.-China strategic competition as both sides compete in the developing world through development finance and investment.

This primer brings up to date how China’s rapid development finance push through the Belt and Road Initiative has influenced U.S.-China relations and U.S. policy towards the developing world. First, it is important to look at how China’s stated BRI policy objectives and mechanisms have evolved since President Xi Jinping’s 2013 announcement. With this backdrop in mind, an exploration of American critiques of how BRI has played out on the ground will follow. Finally, this primer will conclude with the most recent developments in U.S. policy objectives and lay out how efforts to compete with BRI have taken shape and how BRI countries have reacted so far.

This section provides a brief overview of China’s stated BRI policy objectives and guiding principles, which provide a necessary backdrop for analyzing U.S. critiques of the initiative in practice. A clearer image of China’s policy goals with BRI first materialized when the Chinese government published its “Visions and Actions” document in March 2015. Greater clarification on these outlined principles was published in June 2017, when the Chinese government published its “Vision for Maritime Cooperation” document.

Within the “Visions and Actions” document, the National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Ministry of Commerce stated China’s principles for BRI. According to the document, BRI’s principles are:

The Chinese government states that it desires to build a framework for BRI through what it terms “win-win cooperation (合作共赢)”. The concept of “win-win cooperation” holds a greater meaning to the Chinese than what on the surface sounds merely like a public relations spin. The concept appears in numerous speeches about BRI from President Xi Jinping and other high-ranking government officials. For example, in President Xi’s 2015 Boao Forum keynote speech alone, “win-win cooperation” is referenced eight times. According to Dr. Chen Xulong of the China Institute of International Studies, this concept “is rooted in the traditional Chinese cultural values of ‘peace and cooperation’ and is consistent with the principles of peaceful coexistence and mutual benefit.”

John Ross, a senior fellow at the Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies at Renmin University, suggests that this core foreign policy approach of China’s also has an economic basis. He suggests this notion promotes a greater division of international labor that improves the productive comparative advantage capabilities of other nations. He writes that “in China’s conception, economic and cultural interactions are entirely integrated and flow from a common basis. The economic “win-win” flows from benefits derived from the global division of labor. The “win-win” benefits in culture and civilization result from the interaction of different experiences reflected in different cultures, which in turn reflect the differentiated aspects of humanity’s development. Therefore, the outcome – both in the realm of economics and culture/civilization – is win-win.” According to this definition, then, the idea of win-win cooperation should be viewed as a guiding concept for China’s stated BRI principles.

Whether in trade negotiations with the U.S. or in pursuing BRI projects, Chinese government officials frequently refer to ‘China’s Core Interests (核心利益)’ as the foundation on how China interacts with other countries. Given that the Chinese government views China’s core interests as the non-negotiable bottom line of China’s foreign policy and must be taken into account by foreign businesses operating in China, it is critical to explore this concept and how it is applied to BRI. The State Council’s 2011 white paper, China’s Peaceful Development, provides one of the first clear definitions of what the Chinese government considers to be China’s core interests (in order of importance):

China’s domestic and foreign policy goals stem from these overarching elements, including the BRI principles laid out in the 2015 “Visions and Actions” document. However, as pointed out by Zeng, Xiao and Breslin (2015), who attempt to provide a clear definition of China’s core values, this stated definition should not be viewed as the conclusive definition. They write that, “[w]hen new concepts, ideas and political agendas are introduced in China, there is seldom a shared understanding of how they should be defined; the process of populating the concept with real meaning often takes place incrementally.” Therefore, although there are certainly agreed upon bottom lines, China’s definition of its core interests remain open to interpretation. This intentional vagueness gives the Chinese government more flexibility on how it can apply the concept to BRI.

More recently, and in part responding to some of the criticisms of Western countries and parts of the developing world regarding the financial and long-term sustainability of BRI projects, President Xi released a Joint Communique on April 27, 2019, at the conclusion of the second Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation. For instance, the Joint Communique addresses a shared concern by many that BRI energy infrastructure projects are overwhelmingly fossil fuel-intensive. Thus, it is written, “To promote sustainable and low-carbon development, we appreciate the efforts to foster green development towards ecological sustainability. We encourage the development of green finance including the issuance of green bonds as well as development of green technology.” However, many in the U.S. believe that while it is important to include provisions such as these on paper, what matters more, of course, is what happens in practice. It has only been a short while since the conclusion of the second BRI Forum, so it remains to be seen whether these intended improvements will be implemented.

Overall, when responding to China’s stated principles for BRI, there is agreement on the U.S. side that these are indeed positive goals to aspire to. However, most U.S. government officials and scholars have increasingly felt that there is a stark difference between the rhetoric of BRI and its realities on the ground. Many in the U.S. accuse BRI of being a pretense for China’s “debt-trap diplomacy” and desire to establish a military foothold in the Indo-Pacific and beyond, also known as the “String of Pearls” theory. In addition, the U.S. also argues that China’s lending and investment practices have remained opaque despite its rapid growth.

A major issue that the U.S. cites with BRI, and China’s foreign investment more generally, is its lack of transparency. U.S. scholars also often bring up the fact that China is not a full member of the Paris Club or the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which allows the country to evade the need to release data on its lending activities that these organizations require as a prerequisite for membership.

For instance, the Paris Club is an informal group of creditor nations established in 1956 that meets in Paris each month to find solutions to payment problems faced by debtor nations as a form of debt relief, such as when a natural disaster strikes. In these cases, Paris Club creditors often negotiate with debtor nations to reschedule debts or change obligations. Other major functions of the Paris Club involve tracking sovereign borrowing from official creditors, including non-members such as China. Many European countries, as well as Russia, Australia, South Korea, Japan, and the U.S. are members. The World Bank, International Monetary Fund, the Asian Development Bank, and more participate too at Paris Club meetings as their capacity as observers. Although China has attended some Paris Club meetings as an ad hoc participant, it remains outside the purview of official membership. China maintaining its observer status, rather than seeking full membership, is significant because it means that it does not need to operate in accordance with its principles, which includes standard lending disclosure requirements.

Around the world… we see Beijing pressing countries to sign [BRI] MoUs (Memorandum of Understanding), emphasizing peace, cooperation, openness, inclusiveness, mutual learning, and win-win cooperation. That sounds great… And we in the United States must welcome and do welcome any investment in trade that promotes sustainable, responsible development and growth. But after seeing [BRI] in practice for the last few years, there are reasons to question the Chinese Communist Party’s largesse.

For example, China offers substantial financing, usually as loans. But Beijing is not a member of the Paris Club, and has never supported globally-recognized, transparent lending practices. According to an estimate released by the Keele Institute, Communist China is the world’s largest official creditor, lending over $5 trillion worldwide. But China does not publish, or even report, overall figures on its official lending. So neither rating agencies, nor the Paris Club, nor IMF are able to monitor those financial transactions. Chinese Communist Party officials recognize they need to use the language of openness and accountability, but the fact remains that the People’s Republic stands outside of global efforts, including those of the IMF and World Bank, to improve transparency that enhances policy making, prevents fiscal crises, and deters corruption.Ambassador Alice Wells, Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asia

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) and Kiel Institute for the World Economy documented 1,974 Chinese loans and 2,947 Chinese grants to 152 developing countries from 1949 to 2017 in a working paper titled, China’s Overseas Lending. Chinese lending mostly occurs by means of a debtor nation’s state-owned enterprise borrowing directly from a Chinese state-owned entity. The authors write that “[t]his type of company-to-company lending is often not collected by statistical offices of developing countries so that international debt statistics suffer from chronic underreporting.” This means that international organizations like the World Bank, the Paris Club, and OECD are unable to accurately track China’s lending. As a result of this and other influencing factors, the authors found that “about one half of China’s large-scale lending to developing countries is ‘hidden’ and not recorded in the main international databases used by researchers and practitioners alike.” This contributes to the lack of information debtor countries need to fully comprehend the precise amount that was borrowed, as well as the accompanying conditions.

Many in the U.S. argue that as China has become one of the world’s largest creditors, it now has the responsibility to adopt the same lending transparency standards of the other major creditor nations. One reason for this is that the U.S. and other major creditor countries fear that without meeting these standards, BRI investments could cause developing countries that have already received billions of dollars in debt relief deals from the Paris Club or other multilateral institutions to require yet another round of relief spending. That China has resisted modernizing its transparency standards to OECD or Paris Club levels while continuing to pursue non-concessionary loans with countries that are at risk of debt distress will likely serve to feed into the predatory debt-trap diplomacy narrative being pushed by the U.S. as well.

Debt-trap diplomacy is the idea that China, as the creditor country, intentionally provides loans to debtor countries with intention of using this debt as leverage to extract economic or political concessions from the

A study by the Center for Global Development in Washington, D.C. that evaluated current and future debt levels of the 68 countries hosting BRI-funded projects found that 23 of those countries are at risk of debt distress today. In addition, future BRI-related financing has a high chance of adding significant risk of debt distress to 8 of those 23 countries. They found that the Chinese government typically provides debt relief in an “ad hoc, case-by-case manner” because they often do not participate in multilateral approaches to debt relief, such as the Paris Club. Although the Asian Investment Infrastructure Bank (AIIB) adopted existing multilateral development bank rules, AIIB loans comprise only a small percentage of China’s international financing. It is believed that without setting clear standards and improving its debt practices soon, China’s record for managing debt distress will continue to grow increasingly problematic. The implications for rising unsustainable levels of BRI-related debt in developing countries will likely continue to feed the narrative that China is actively pursuing debt-trap diplomacy as part of its grand strategy.

The Belt and Road Initiative. Who can fault [China] for trying to develop the parts of the world that are important to them? They want to secure their supply chains for precious metals, food, energy. I get that, no problem…. [But] I get really concerned because what they’re doing is making these proprietary loans. They’ve already foreclosed in Colombo and Karachi, they have this 99-year lease in Cambodia now, they’re thirty clicks down the coast in Djibouti from us. We see the expansion of their interest. If it’s just trade, no problem. But I have a hard time saying that when you’re going into a place like Colombo and you foreclose on your weak partner and then you turn that port into a military port, it raises questions in my mind about what the original intent was.

Senator David Perdue (R-Georgia)

The String of Pearls theory refers to the idea that a part of China’s grand strategy involves encircling India, East Africa, and parts of the Middle East both commercially and militarily as a means of securing trade, oil imports through the Malacca Strait, and sea lines of communication. In support of this theory, according to Brig. (Ret.) Gurmeet Kanwal, an adjunct fellow with the Wadhwani Chair in U.S.-India Policy Studies at CSIS, highlights the acquisition of several ports throughout the Indian Ocean Region:

In China’s grand strategy, Gwadar is an important foothold that is part of its String of Pearls strategy for the Indo-Pacific. Other “pearls” in South Asia include Myanmar’s Kyaukpyu port and Hambantota in Sri Lanka. Maldives has also negotiated an agreement with China for the long-term lease of a port…. Both China and Pakistan view the development of Gwadar port as a win-win situation. The CPEC is part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that seeks to extend China’s strategic outreach deep into the Indo-Pacific region and counter U.S. influence in the Indo-Pacific.

Thus, it is believed by many scholars in the U.S. that China’s port acquisitions and development are evidence that it is using BRI loans to economically coerce nations to trade sovereignty for debt relief or investment incentives. One of the most cited examples by the U.S. of China’s debt-trap diplomacy is the 99-year Hambantota Port handover in Sri Lanka. More recently, many in the U.S. were alarmed when The Wall Street Journal reported on July 22, 2019, that the government of Cambodia was to grant China a 30-year lease on one of its ports and permit both troop stationing and weapons storage. In addition to questions of commercial viability of the port, satellite imagery provided evidence that a military-grade airport was being constructed. Although both the Chinese and Cambodian governments deny these allegations, western scholars and government officials remain highly skeptical.

The U.S. response to BRI since the 2016 ICAS report has begun to take a clearer shape with the passage of both S.2736 – Asia Reassurance Initiative Act of 2018 (ARIA) and S.2463 – Better Utilization of Investments Leading to Development Act of 2018 (BUILD Act). These acts directly take aim at BRI with the intention of reasserting the U.S. footprint primarily, though not exclusively, in the Indo-Pacific region. These Acts have led to the creation of the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) and most recently, the Blue Dot Network (BDN).

We want transparent transactions, not debt traps…. China doesn’t play by that same set of rules. Its values are simply different. You see that in places as diverse as Africa, where they often ship in their own labor, creating jobs for Chinese workers rather than for those in the local economy. It’s using the debt trap which I referred to just a moment ago to put these countries in a place where it isn’t a commercial transaction, it’s a political transaction designed to bring harm and political influence in the country in which they’re operating….

The State Department wants to work with each and every one in this room tonight, American companies and foreign companies alike. We want to achieve these goals because we think we have the model that will make not only America but the world more secure.Mike Pompeo, U.S. Secretary of State

These U.S.-led initiatives reportedly seek to provide the developing world a relatively more sustainable and transparent alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative. However, according to David Stilwell, American foreign policy in these regions does not aim to replace China or force other countries to make a choice between the two countries. Rather, the U.S. is pursuing a policy of pluralism, which he defines as “the coexistence of multiple things—whether states, groups, principles, opinions, or ways of life. In short: diversity, openness.” This idea of pluralism suggests then that the DFC and BDN should not be viewed as replacements for China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Rather, the intention is to encourage healthy competition that provides lower-income and lower-middle-income countries an alternative to Chinese investment if they should so choose.

In accordance with the BUILD Act of 2018, the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) is to be an executive agency that brings together the capabilities of the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) and USAID’s Development Credit Authority (DCA) to finance private development projects in lower-income and lower-middle-income countries. Notably, the initial spending cap of DFC investments will be $60 billion, doubling OPIC’s $29 billion cap.

According to the FY2020 Congressional Budget Justification for the DFC, the DFC will compete with the Chinese model of state-directed lending that it is argued has led to developing countries incurring dangerous levels of debt. The DFC advertises it will provide higher sustainability and transparency standards under a private sector-led model. To achieve this, they write:

The United States must compete, however, for these positive outcomes. Other countries are seeking to project their economic and geopolitical influence. China, for instance, has promised the resources to initiate long-term efforts to invest over $1 trillion in Eurasia, Africa, and Latin America. Rather than meeting competitors at the lowest common denominator, or engaging in practices that distort markets, the United States will use its development finance tools to pursue development and national-security objectives, while projecting American values and norms and promoting responsible business practices in partner countries.

Adam Boehler is the current CEO of DFC. He officially replaced David Bohigian on December 2, 2019, who had previously led OPIC, while OPIC was still operational. The DFC’s Board of Directors is comprised of both public and private sector individuals, with Secretary of State Mike Pompeo as its Chairman, USAID Administrator Mark Green as its Vice-Chairman, and Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross as a board member. This Board of Directors makeup is emblematic of U.S. intentions to better support and complement the State Department and other agencies for the advancement of the U.S.’ foreign policy agenda.

According to DFC’s Chief Operating Officer Edward Burrier, there are key differences between OPIC and DFC. One of them is that Congress expects the DFC to play a larger foreign policy role in the projects that it supports. One major criticism of OPIC was that it was reactive, rather than proactive, in the development space. Partially as a result of restrictions placed on how the former agency could operate, OPIC was viewed by some as unable to provide the diversity of financial tools needed to compete with BRI. Under the BUILD Act, however, DFC is granted more flexibility as to the types of projects it can support and where it can support them, which is where the foreign policy objectives come into play. For instance, in addition to providing direct loans, loan guarantees, and political risk insurance in the same ways that OPIC was authorized to, the BUILD Act now grants DFC the authority to conduct technical assistance and feasibility studies and make equity investments in projects.

The DFC has already been hard at work to begin securing new contracts for development opportunities. Adam Boehler has traveled to locations in the Indo-Pacific, Latin America, Africa, and more to strengthen relationships with potential partners and highlight the DFC’s ability to spur private investment in those regions. Notably, his efforts have led to a multi-million dollar deal with Egypt in which Texas-based Noble Energy and the DFC will finance and manufacture petroleum products in partnership with the Egyptian company Dolphinus Holdings. Boehler also recently signed a letter of interest with Mexico to finance the Rassini natural gas pipeline that will reportedly be worth $632 million. In his first official travel following the official launch of the DFC, Boehler met with Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyễn Xuân Phúc on January 8 and Indonesian President Joko Widodo on January 10 as a display of U.S. commitment to the Indo-Pacific region, exploring potential investment opportunities in transportation, energy, the digital economy, and more.

In addition to energy infrastructure, the DFC has also begun a push in the telecommunications sector. Given U.S. concerns about the spread of Huawei and ZTE in the developing world, Boehler has indicated that the DFC plans to tap into its $60 billion investment cap to decrease the cost of developing more secure and sustainable 5G infrastructure for developing countries seeking alternatives to Chinese telecoms. Boehler was quoted towards the end of 2019, “The U.S. is very focused on ensuring there’s a viable alternative to Huawei and ZTE. We don’t want to be out there saying no. We want to be out there saying yes.” Although no clear investment plans have been released yet, one potential mechanism would be for the DFC to provide loans for equipment purchases that would make European or other non-Chinese telecoms providers competitive with Huawei or ZTE in those regions.

On November 4, 2019, OPIC announced the Blue Dot Network (BDN) at the Indo-Pacific Business Forum in Thailand. The BDN is “a multi-stakeholder initiative that brings together governments, the private sector, and civil society to promote high-quality, trusted standards for global infrastructure development in an open and inclusive framework.” The BDN will initially be spearheaded by OPIC (with DFC now taking over this leadership), Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, and Japan Bank for International Cooperation. Although this initiative is in its embryonic stage and lacks a concrete framework as of the publication of this primer, it is advertised as a more sustainable option than BRI by only financing infrastructure projects that are proven to be market-driven, financially viable, and transparent.

Through initiatives such as One Belt One Road, Beijing has flooded much of the developing world with hundreds of billions of dollars in opaque infrastructure loans, leading to problems such as unsustainable debt burdens and environmental destruction and often giving Beijing undue leverage over countries’ sovereign political decisions. We welcome fair and open economic competition with China, and economic engagement between China and other countries that adheres to international best practices such as transparency, responsible lending, and sustainable environmental practices. But where China acts in a manner that undermines these principles, we are compelled to respond.

David Stilwell, Assistant Secretary, Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs U.S. Department of State

Around the same time, on November 4, 2019, U.S. Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross and National Security Advisor Robert O’Brien introduced the Blue Dot Network (BDN) at the 35th Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) summit in Bangkok, Thailand. The initiative is being marketed as an alternative to China’s debt-trap diplomacy, which, according to Mr. O’Brien, would counter this trend. To help kick off the initiative, the U.S. signed statements pledging to coordinate with partners on investments of $17 billion in liquified natural gas and other Asian energy projects.

Waning U.S. influence in the developing world over the years has led to a mixed reception amongst the BDN’s initial primary target audience -the ASEAN countries. Although the U.S. presence in Southeast Asia had been waning well before Trump took office, the U.S. departure from the Trans-Pacific Partnership seemed to imply that the Administration would continue further down this path. According to Dr. Tang Siew Mun, Head of the ASEAN Studies Centre at Singapore’s ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, the US “has been playing catch-up to China’s charm offensive [in the Indo-Pacific] since the turn of the new century.” Secretary Ross attempted to dispel this belief at the ASEAN summit, saying “[we] are here permanently, and we will be continuing to invest more here, and we will be continuing to have more bilateral trade, and I’m spending much more time in the region.” However, the fact that it was Secretary Ross introducing the BDN and delivering these words as opposed to Trump himself, unlike Xi Jinping with the announcement of the Belt and Road Initiative, seemed to drive home this sentiment even further for some.

On December 20, 2019, President Trump signed into law H.R.1865 – Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020, which included provisions to reauthorize the Export-Import Bank of the United States (Ex-Im) through the end of 2026. Ex-Im, an independent Executive Branch agency, is the official export credit agency of the United States that provides assistance to American businesses with financing tools when they are unable to receive financing from private sector lenders. According to its website, the purpose of these financial tools is to help level “the playing field for U.S. goods and services going up against foreign competition in overseas markets, so that American companies can create more good-paying American jobs.”

A major provision under the reauthorization of Ex-Im is found within Sec. 402 of H.R. 1865, titled the Program on China and Transformational Exports. The purpose of the program is to support the extension of loans, guarantees, and insurance that are competitive with the rates and terms extended by China and other covered countries. A “covered country” is designated by the Secretary of the Treasury, and is defined as a country whose financing terms and conditions are not based on participation within or do not comply with that of the OECD’s Arrangement on Officially Supported Export Credits. Thus, China’s BRI lending is a clear target for this Ex-Im program, as it aims to create a level playing field by “directly [neutralizing] export subsidies for competing goods and services financed by official export credit, tied aid, or blended financing provided by the People’s Republic of China”.

The amount of funding reserved for Ex-Im’s Program on China and Transformational Exports will be potentially highly significant. Sec. 402 (3)(C)(A) that relates to financing for the program aims to reserve, at minimum, 20 percent of its applicable amount in support of the program. This would provide direct support to U.S. businesses seeking to compete overseas with China in areas such as 5G, artificial intelligence, renewable energy, semiconductors, financial technologies, water treatment, and more. However, as the U.S. has made clear on numerous occasions, it desires Chinese financial practices to meet global standards. As such, an exception to subparagraph (A) was included in which the “Secretary of the Treasury may reduce or eliminate the 20 percent goal” if it is reported to Congress that China is in substantial compliance with the financial terms and conditions of the OECD Arrangement, as well as the rules and principles of the Paris Club.

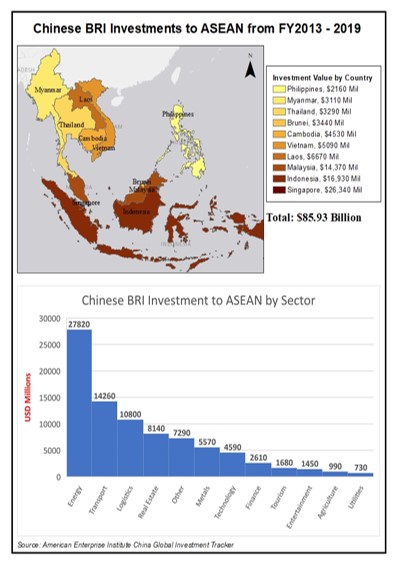

As the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation has only just recently been launched and the Blue Dot Network continues to lack a unifying framework or signed agreement between the U.S., Japan, and Australia, more questions than answers have arisen on U.S. efforts to compete with and counterbalance China’s Belt and Road Initiative. According to the Asian Development Bank (ADB), $26 trillion in infrastructure investments are needed in Asia alone from 2016-2030 “to maintain 3 to 7 percent economic growth, eliminate poverty, and respond to climate change.” Meanwhile, aid and investment in ASEAN countries from the U.S. government through all implementing agencies such as USAID and U.S. Department of State from FY2013-2019 have totaled about $6.65 billion, with OPIC (now DFC) projects representing $602.2 million. In the same period of time, Chinese BRI investments in ASEAN countries have reached $85.93 billion. To be sure, advertising quality investments over quantity is an important tactic, but, as Peter McCawley, a former executive director of the ADB writes:

…the level of spending that donor countries offer is important as well. Donors need to put their money where their mouth is. After all, a road is a road, whether it is built with US or Chinese money. At present, it seems that the Chinese are prepared to fund the construction of infrastructure in Asia, while the US is not.

Normally, one would not necessarily include foreign aid data in a comparison focused on development finance. However, given that BRI projects remain loosely defined and are constantly expanding in scope, BRI activities have been seen to include not only investment in traditional hard infrastructure, but also investment in soft infrastructure. This can include trade deals, tourism, and other people-to-people ties such as education and cultural exchanges. Thus, with BRI at the foundation of China’s grand strategy and being enshrined in the Chinese Constitution, certain foreign aid projects from China, such as those deriving from the China International Development Cooperation Agency, could theoretically be considered under the BRI umbrella.

U.S. attitudes have clearly shifted from that of ambivalence to outright hostility towards BRI. However, some of the more egregious examples that the U.S. cites as proof of China explicitly engaging in debt-trap diplomacy, such as the Hambantota Port handover in Sri Lanka, do not tell the full story. According to a report from the Rhodium Group in April 2019 that focused on debt sustainability for 40 cases of BRI-related external debt renegotiations, three major key findings were found: debt renegotiations and distress among borrowing countries are common, asset seizures are a rare occurrence, and despite its economic weight, China’s leverage in negotiations is limited. Although the Sri Lankan case “serves as a cautionary tale of the danger of borrowing too much from China”, that particular case is more of an outlier than the norm. They conclude that “at the very least, the large number of debt renegotiations seen so far will likely serve as a brake on the narrative of accelerating Chinese outbound lending along the Belt and Road.”

A 2017 Baker-McKenzie report notes that although Chinese state-owned enterprises have enjoyed early success, they will face increasing challenges to win or remain on projects. There have been occurrences where a Chinese firm was removed from projects, blacklisted by the World Bank, while yet another suffered from labor strikes. At the same time, international competition has led Chinese firms to lose project bids, such as a Japanese firm winning a high-speed railway deal in India and Turkish firms winning airport construction contracts in Kuwait. As developing countries become increasingly cautious about taking on unhealthy levels of debt from China, more sustainable options from the U.S. could appear much more attractive in the long term. Therefore, the introduction of the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation and the Blue Dot Network has the potential to spur ‘win-win’ competition in the developing world. In accordance with U.S. notions of pluralism, Chinese and U.S. development can occur in tandem with one another which could have the effect of forcing China to improve the quality and transparency of its investments to remain competitive.

What remains clear, however, is that unless the U.S. can prove to recipient countries that it is serious about these initiatives and that the higher quality assurance and transparency standards are worth meeting, it will be difficult for the DFC or Blue Dot Network to compete with the easy loans that China’s BRI investments offer.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2025 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

The U.S. Auto Industry Has Not Lost Yet—But It Must Compete Smarter