Research Associate &

Manager, Maritime Affairs Program

China is in the middle of building a resilient network of largely bilateral partnerships in space operations at a point where the United States’ capabilities and attention to cross-border relationships in the space realm appear to be lagging. Their nature is not only topically but regionally widespread as China continues to garner collaborations with nations from almost every continent and across varying levels of national economic strength.

Over the last few years, the focus of the China National Space Administration (CNSA) has turned towards the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS), which it began publicly formalizing with its Russian counterpart Roscosmos in March 2021. Between the existence of this program and several other cases, it is thoroughly supportable that China has long had their attention on being in and then retaining a position of relevance in outer space and is interested in, primarily though its CNSA, establishing a wide-spread, variously-capable collective of established partners from around the world on outer space issues.

Traditionally, the U.S. has relied on multinational treaties to maintain order, but the power of such non-binding agreements appears to be waning in the modern age. In addition to assigning a clear, collective spearhead for U.S. collaborations on space, the U.S. needs to instill confidence in the modernity and attention being given to its space operations, or risk losing traction and influence among the rising number of interested stakeholders and capable parties.

Despite the historically high levels of tension and lack of a renewed science and technology cooperation agreement, it is a mistake to discount collaboration as an option for the U.S. and China on space issues. Be it through addressing space junk, renewed threats of nuclear missiles, or the lack of communal regulations on space, the U.S. must do more to publicly keep itself not only relevant but a leader, less it fall short as China expands its diplomatic inroads on space.

Even more than the historically high levels of mutual distrust, the 2011 U.S. Wolf Amendment is the single most important barrier to U.S.-China cooperation in space. First and foremost, if there is any desire at all for rapport to be reestablished between these two nations on this front, this law needs to be reevaluated and addressed.

China is in the middle of building up a strong network of partnerships in space operations at a point where the United States’ capabilities and attention to cross-border relationships in the space realm appear to be lagging.

Particularly over the last five years, China has been building a stronghold of space diplomacy brick-by-brick through small-scale bilateral agreements that will eventually result in a fairly strong and versatile mix of partnerships that China can fall back upon and benefit from. Although more arduously tedious and complex, this bilateral-based system is arguably more resilient and effective, as it permits any agreements or partnerships to be personalized to those two states’ circumstances and bilateral affairs.

Furthermore, unlike international treaty systems—which the United States’ space operations largely continue to rely upon—none of these bilateral partnerships are necessarily dependent on another, nor is there a mass agreement or memorandum of understanding that can be threatened by a single party’s action—or inaction. In concept, the ‘hub’ can remain relatively undamaged if one of its ‘spokes’ becomes detached. At least conceptually, it is not as inflexible of a global structure compared to one of its multi-dependent counterparts; evidenced by the sudden suspension of Arctic Council proceedings in March 2022 following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This ‘hub-and-spoke’ concept, as some refer to it, is not unfamiliar to the West, as some see it being applied by the United States in its establishment of post-Cold War era military alliances across Asia.

However, for one reason or a dozen others, the U.S. has not appeared to broadly apply this partnership model to its outer space operations; at least not yet. Other nations—Japan, India and Russia being at the forefront—are also clearly continuing to reach for historical milestones in space history as well in an apparent drive to not be left behind. Meanwhile, China’s decades of establishing more personalized, direct, bilateral cooperations in space—of varying sizes and depth—may now be paying off to its considerable advantage. Be it by partnering with China’s efforts or breathing oxygen into a semi-binding multilateral system, the U.S. government leadership needs to show more initiative on space diplomacy else be content with truly becoming lost in the past.

China’s partnerships and agreements—a phrase being applied here generally and not always in reference to official science and technology agreements (STAs)—on outer space are both widespread and simultaneously progressing, with at least two lasting partnerships dating back three decades. As soon as China began participating in international space cooperation in the mid-1970s, it worked to broaden its space cooperation across sectors and in design. The nature of these bilateral agreements is not only topically but regionally widespread, as China continues to garner collaborations with nations from almost every continent and across varying levels of national economic strength.

In July 2022, the China National Space Administration (CNSA) summarized its widespread accomplishments, noting it had “signed 149 space cooperation agreements or memorandums of understanding with 46 national space agencies and 4 international organizations, established 17 space cooperation mechanisms, and participated in 18 international organizations including the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space.” In this particular release on international cooperation in outer space, CNSA emphasized three areas of cooperation—Satellite Engineering Cooperation, Lunar and Deep Space Exploration, and Space Application Cooperation—though the most dominant of these appears to be in satellite collaboration.

Between 1985 and 2000, China reported signing inter-governmental or inter-agency cooperative agreements, protocols or memorandums, and establishing long-term cooperative relations of some form “with a dozen countries, including the United States, Italy, Germany, Britain, France, Japan, Sweden, Argentina, Brazil, Russia, Ukraine and Chile.” From 2018 to 2020 alone, China jointly developed and successfully launched satellites with France, Pakistan, Brazil, Austria, and Argentina, among other nations, the purposes of which were largely for scientific research purposes. In December 2019—the same month in which China successfully launched a satellite with Brazil—China launched the Ethiopian Remote Sensing Microsatellite for Ethiopia. Brazil notably holds one of the longest established space partnerships with China, dating back to the China-Brazil Earth Resources Satellite (CBERS) program established in 1988 which has seen at least six launches since and, as one observer describes, was “meant to allow the two countries to expand their footprint in space without the United States’ or Western involvement.”

Cooperative efforts have also come in the form of space technology development agreements, such as the memorandum of understanding (MoU) signed between Serbia and China in June 2020. Over the last three years, CNSA has continued to successfully pursue space partnerships and projects with both government and non-government parties in places such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Brazil, France, Belarus, Pakistan, Venezuela, Egypt, and in 22 different African nations including South Africa. Notably, these broad efforts are not exclusively limited to the bilateral level, as is proven by the 1st meeting of the BRICS Joint Committee on Space Cooperation being held in May 2022 and CNSA’s ongoing discussions with the African Union’s African Space Agency since 2018.

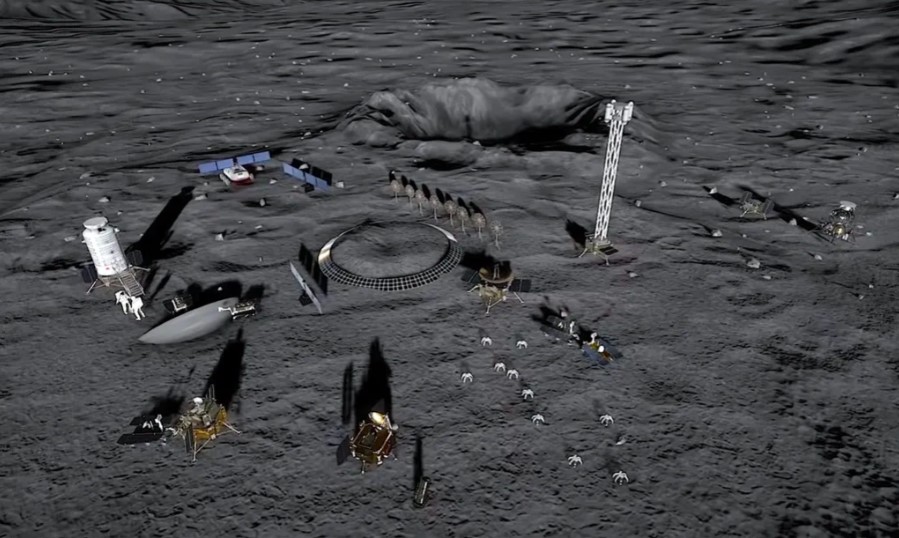

While China continues to launch joint satellites and is now dabbling in side projects like space tourism, China’s attention currently appears to be honed on fostering its International Lunar Research Station Cooperation Organization (ILRSCO) initiative, which many openly regard as a parallel project to the United States-led International Space Station or Artemis Program.

In March 2021, the CNSA and their Russian counterpart Roscosmos signed the MoU on Cooperation in Construction of International Lunar Research Station, followed one month later by the jointly issued Partner Guide for International Lunar Research Station and a “Guide for Partnership” in June 2021. In November 2022, the two parties reaffirmed their joint commitment to bilateral space cooperation by signing a five-year deal on space cooperation for 2023-2027, most of which is centered around this lunar research station.

Even before the official establishment of its ILRSCO, China was attracting third parties to join, succeeding at a rate which many would regard as considerably and steadily successful. The expansion of ILRS-related partnerships started truly flourishing in early 2023, such as on April 25 when CNSA and the Asia-Pacific Space Cooperation Organization signed a joint statement on cooperation in international lunar scientific research stations. In May 2023, the CNSA’s Chinese Lunar Exploration Program (CLEP) gave a detailed public presentation on the ILRS concept, which they describe as being “proposed by China and jointly built by many countries,” and began openly inviting participation.

Since June 2023, South Africa, Venezuela, Azerbaijan, Pakistan, Belarus, the University of Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates, Brazil, and Egypt have officially signed agreements or MoUs specifically related to the International Lunar Research Station. There are, as one analyst described it in early December, “just a handful of countries [that] have said they will support the ILRS, [but] China is gradually making inroads.” Even amidst China’s economic slowdown in 2024, these inroads will continue to deepen and multiply so long as the ILRS mission remains in the minds of Beijing’s leadership.

To be frank, it is virtually impossible to nail down a specific number of space-specific agreements acknowledged by China. Between conflicting estimates, language barriers, outdated statistics and potential cases of closed-door events, the true number may never be known. With the increased potential of the space realm being militarized, this truth is even more self-evident. That being said, having this exact number is not necessary to exhibit the breadth and consistency of China’s space-related partnerships.

Foreign observers have been tracking China’s extensive activities in space at rates which, while not always matching those released by China, are considerable. The U.S. Congress’ U.S.-China Economics and Security Review Commission (USCC) has been releasing public reports on the subject for over 15 years. As summarized in a November 2019 USCC report, China has overseas space tracking stations in six countries (Australia, Chile, Kenya, Namibia, Pakistan, and Sweden) and also sells space-related technology and services to many countries (including Algeria, Argentina, Belarus, Bolivia, France, Indonesia, Laos, Nigeria, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Venezuela) while having launched 20 satellites on behalf of 13 countries between 2007 and 2018. As one eye-catching example, the Espacio Lejano Station is a comparatively large, Chinese-owned space monitoring and tracking station in Argentina’s Patagonia region which opened in March 2018 after finally being approved by Argentina’s congress in February 2015. Also known as Deep Space Ground Station, its existence has drawn voices of concern since before its official conception as it, in one description, is a “50-year equity-free agreement [that] restricts Argentina’s sovereign control of the land and operations, provides exhaustive tax exemptions and enables the liberal movement of Chinese labour, working under Chinese labour law.”

In another June 2023 scientific study on China’s international science and technology agreements, 18 countries were listed as having confirmed signing STAs specifically related to space. Though most of which were described as “non-specific agreements” made on outer space issues, the range of agreements across countries of all income levels is noticeably broad, indicating the multi-faceted approach of China’s space strategy.

Source: Caroline S Wagner, Denis F Simon, China’s use of formal science and technology agreements as a tool of diplomacy, Science and Public Policy, Volume 50, Issue 4, August 2023, Pages 807–817, https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scad022

Between these two reports—their potential subconscious leanings notwithstanding—CNSA’s own 2022 official release previously detailed above, and other individual confirmations over the last eight months of additional such agreements being signed, two conclusions are thoroughly supportable:

This strategy of widespread, individualized partnerships is not full-proof, evidenced by the current, questionable state of health of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Such a bilaterally-built network can still be dismantled, as is shown in the case of space relations by the UAE dropping as a partner in March 2023 to fly on China’s Chang’e-7 lunar mission over a conflict with U.S. sanctions. Germany has also pulled back in space cooperation with China recently. In September 2023, Berlin’s economy ministry decided to not allow Shanghai Spacecom Satellite Technology to acquire the 45% minority stake of German satellite startup company EightyLeo, as the Shanghai company already owned 53% of the company. Still, with how China is constructing these agreements and partnerships, conceptually, the removal of one does not naturally disrupt or break the whole system. It is comparatively more resilient than its multinational counterpart—a system reliant on adherence to the same exact guidelines—the power of which can deteriorate if even one party breaks form.

Regardless of how well individual partnerships may or may not work out, this type of system places China at the discussion table; a spot they have long coveted and would never want to lose. China is successfully using formal bilateral science and technology agreements (STAs), as two researchers directly described it in 2023, “as a tool of diplomacy,” “possibly to establish political goodwill,” and potentially even as a “critical part of China’s priorities in establishing formal relationships.” While historic case studies depict the successes of science diplomacy and the concept of STAs themselves being diplomatic tools is not novel, the heavy extent to and breadth of which China is applying STAs in their diplomatic strategy may be unique.

Furthermore, once players are ‘at the table’ they can communicate more than simple goodwill. As one observer described at the onset of the China-Russia Lunar Base Cooperation Agreement talks, “[w]ith their agreement, the partners are signalling an alternative to a U.S.-led order in space.” For years, and especially since the turn of 2024, this open awareness and discussion of a renewed ‘cold war’ in space has increased among observers, policymakers and government officials alike. Between these points and Beijing’s own extensive plans for its space missions in 2024, China at least strives to be at the decision table in space issues, and its decades of establishing, strengthening and expanding bilateral cooperation on outer space is paying off.

While it is hard to accurately predict whether—or exactly when—space will become the next frontier of confrontation or competition, it would be foolish for the U.S. to not stay active in the field; and not just active but highly so. If nothing else, retaining a voice in—and uninhibited access to—the physical space where thousands of satellites live—satellites that provide everything from weathercast support to telecommunication routes—is vital to national security. In an increasingly digitized world, there is no region more important to retain influence within than space.

Pushing for Multinational Agreements and Treaties

Traditionally, the U.S. has relied on multinational treaties to maintain order. Although the existing 1967 Outer Space Treaty lays the groundwork for space exploration, many have called for its reevaluation as nearly six decades of technological growth, diplomatic restructuring, and national strategic repurposing have passed since its establishment. Whether or not a renewal is actually capable of being—or should be—agreed upon and then successfully applied within the next decade is the true question. Unfortunately, such discussions are likely to be as slow to progress as those for international maritime law agreements such as the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea or the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Regardless, to retain or gain influence, interested parties need to be in those meetings, if not at the head of them.

Recent U.S. leadership has clearly understood this need, leading to the launch of the Artemis Accords in October 2020 by the U.S. State Department and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). At present, these accords appear to be an ongoing, unofficial case study for the relevancy of a “non-binding set of principles designed to guide civil space exploration and use in the 21st century.” As of February 15, 2024, when Uruguay officially joined, it had 36 signatories in total and remains open for more.

While such a set of principles can be a positive addition to the conversation, such non-binding principles—especially ones with a low percentage of signatories—can end up becoming a useless tool as they tend to rely on a nation’s credence to maintaining rapport and strengthening soft power. Put simply, some nations do not care what other nations believe of their actions and policies so long as their national priorities are met. At its worst, such non-binding agreements can unknowingly create a sense of complacency in leadership because of the feeling that ‘something’ is already being done to solve a problem. Even if such agreements were not phrased in overly simplistic terms that could be interpreted from several angles, in such a split world as the one we live in today, such non-binding agreements are losing their power as states find ways to successfully suffer through or entirely avert any consequences of breaking the principles. It is difficult to trust the true efficacy of the Geneva Convention, for instance, when hearing regular reports of law-breaking atrocities taking place in the Russia-Ukraine War or within the Israel-Hamas war in the Gaza Strip.

With just over three years in existence, the Artemis Accords can still be considered young, and the signatory list is notably still growing. Some have regarded the coexistence of the Artemis Accords and China’s similarly growing ILRS program the “dawn of astropolitical alliances that will have far-reaching ramifications for the bifurcation of the framework of global space governance.” The U.S. needs to instill confidence in the modernity and attention being given to its space operations, or risk losing traction. Furthermore, the question must be asked: Is a multinational accord more detrimental than constructive if the key players cannot be convinced to participate?

Watching and Gathering Intelligence

As expected, the United States is not ignorant to China’s activities in outer space. Across speeches, interviews and reports, it is clear that the U.S. government—civilian and military—are attentive to China’s space activities and concerned about Beijing’s intentions.

The more interesting note to ponder is how several parties across Washington have dedicated time and resources specifically towards publicizing the United States’ awareness of China’s activities. The Foreign Affairs Committee, for instance, has a webpage dedicated to China’s space program and their objectives in space, which emphasizes the “dual-use” and blended nature of China’s civilian and military programs as they relate to space. The question remains, however, whether or not these concerns are being translated into action, or to what extent these apparent signs of attention have remained a priority. While the aforementioned Foreign Affairs Committee’s webpage was last updated in November 2022, the last time that the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission (USCC) held a hearing on space was in April 2019 and the Committee’s last space-specific research report, titled “China’s Space and Counterspace Activities,” was released May 2020.

Logically, given the announcement of the ILRS in 2021 and the hundreds of other notes of progress in other nations’ space activities since then, these public notes of attention should be more recently updated if the U.S. cared to remain relevant on the issue. Either these conversations and their information have been moved entirely to behind closed doors or they are not taking place. The former would be understandable, especially with the apparent militarization and securitization of outer space, that information is more sensitive now and thus must be kept confidential or classified. Prudence is essential in selectively retaining or revealing information or intelligence. Simultaneously, as an observer, it can be difficult to accurately diagnose the state of interest if appearances are left so unkempt. Perhaps that is Washington’s idea going according to plan.

Selecting the Proper Spearhead for U.S. Space Operations

Typically, project efficiency is at its highest when there is a clear and proper delegation of tasks. Similarly, countries usually rely on a hierarchy system in which a single official or organization—i.e., the U.S. Department of State or Foreign Minister of the People’s Republic of China—represents that country on the world stage. At present, the United States has three institutional representatives heading U.S. space operations: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (an independent government agency); U.S. Space Force (a service branch of the armed forces); and U.S. State Department (an executive department of the U.S. federal government). Dividing responsibilities within this trifurcated system—the members of which each have their own strengths, priorities and abilities—can be highly fruitful, so long as all parties understand their roles. At present, it is difficult to distinguish who exactly within these institutions is spearheading U.S. space operations, or if there is a spearhead at all, especially when it comes to U.S. grand strategy in space collaboration.

NASA is an independent agency not able to represent Washington and the United States in an official diplomatic capacity. While this could bring troubles establishing official agreements, diplomatic rapport could still be established and people-to-people conversations still be held; the type of engagements that are vital in successful international science and technology partnerships.

The U.S. Space Force, formally established as a military branch on December 20, 2019, is itself still young, but its highly experienced personnel are not. However, its reputation—and in some cases even its existence—is still developing. Since its leadership declared ‘full operational capacity’ on December 15, 2023, it has been notably more outspoken, such as in mid-February when Chief of Space Operations Gen. Chance Saltzman outlined plans to optimize the Space Force for Great Power Competition. Still, the state of the Space Force is not all sunshine and roses. In early February 2024, it was announced that a multibillion-dollar, highly classified communications satellite program for the Space Force, originally contracted with Northrop Grumman in 2020, was dropped due to increased costs, difficulties developing its payload and schedule delays.

This is not to say the Space Force should not be involved in cross-border space collaborations; they should be, but in a supportive role. Also, very few countries currently have a proper equivalent to the U.S. Space Force—a space arm of the national military—so their presence in diplomatic activities would be more reaching and tenuous than a State Department counterpart. Unless the U.S. wants to intentionally advertise its militarization of outer space, the Space Force should not take the head of negotiations on space collaborations.

Last, the State Department should be considered a leader in U.S. space operations because of its identity as a co-leader of the Artemis Accords. Federal departments have been establishing MoUs and science and technology agreements for decades, but the State Department’s role in the Artemis Accords is not described as that of a simple proxy to host a single or occasional meeting. The Artemis Accords is an ongoing, multifaceted program that is not only expected to continue growing but also anticipated to become a major cornerstone of U.S. relevance in outer space relations. While less prioritized with knowing scientific particulars or having security awareness compared to their counterparts at NASA and in the Space Force, respectively, the State Department is an official connecting point to plant and communicate U.S. interests on outer space.

In fact, this department’s vault in relevance to outer space relations is testament to the increasing—and lasting—importance of interstate relations to space issues. In light of how China is approaching its space diplomacy, the U.S. may no longer have a choice but to push for such engagements or risk seeing their influence fade. As one observer summarized in December 2023, “the United States should not be complacent” but engage directly in places like the Middle East. NASA Administrator Bill Nelson’s visit to the UAE in December 2023 as part of the first-ever Space Agencies Leaders’ Summit, one month after a MoU was reportedly signed by the UAE’s University of Sharjah to cooperate on China’s ILRS, is a recent example of such engagement. Similar ‘races’ are being reported in Africa, where “Chinese companies have been capitalizing on this [wide need for collaborations on space] for years. It’s now that the U.S. is waking up to this,” Nigerian space scientist Temidayo Oniosun elaborated at a public discussion on the topic in late 2023. Clearly, active diplomatic engagements on space issues will be essential for the U.S. to remain relevant and influential.

The U.S. response would need to be a joint, balanced effort between members from NASA, the U.S. Space Force and potentially the U.S. State Department (or another official diplomatic unit such as U.S. embassies) as each lacks a necessary element to reach the optimal outcome. As three U.S. military researchers recently summarized, “without increased collaboration and prioritization across the federal government, the U.S. will not see the same success in this Space Race as it did against the Soviet Union.” The stage is very different than half a century ago, especially with technological capabilities and the number of interested parties rapidly expanding with every year that passes. Collecting a working group to address U.S. holistic international efforts in space would be a logical next step for Washington, though that is a task easier said than done.

Many observers are calling U.S.-China cooperation highly limited, and rightfully so. Alongside years of seemingly endless tensions and frustrations, the failure to renew the U.S.-China Science and Technology Cooperation Agreement by its February 27, 2024 deadline only supports this disbelief in the possibility of cooperation.

However, the logic remains that “engaging with China is critical to enable space operations so that space can continue to be used in a sustainable manner that is equitable and accessible for all.” Yes, national security must be maintained, and yes, there is no easy solution, but those are poor and lazy excuses to block off such a progressive opportunity. Not only is it rational to maintain communication channels for coordination on common issues, such communication can support both domestic and bilateral economic, social and political relations, as it came to be during the Cold War. As President Joe Biden was transitioning to his presidential post in 2020, his space advisors openly urged cooperation with China, calling a lack of inclusion “a failing strategy,” “short sighted” and “not the mark of a good leader.”

With military-to-military communications recently re-established between the U.S. and China following the November 2023 summit in San Francisco between President Joe Biden and President Xi Jinping—an agreement that was reconfirmed a few days later by the Chinese military—perhaps there is a logical chance for mutually-beneficial cooperation in the space domain. There is precedence for U.S.-China bilateral agreements on specific issues, such as the December 1988 memorandum of agreement on liability for satellite launches. Directly following the San Francisco summit, NASA took the opportunity to initiate plans to cooperate on moon rock research with CNSA, which observers said was a “huge” step they were “very happy to see.” The U.S. also announced a potential proposal to exchange missile launch notifications with China to support mutual nonproliferation and trust. The expected rules of engagement may have very well shifted with these November agreements alone, even if that shift takes time.

Space debris (also known as space junk) should be at or near the top of collaborative discussions. This could be a short-term partnership—a test, if you will—that would be beneficial to all parties involved. It is also an increasingly imminent problem, as many reports over the last few years have described, with no established plan yet made for its resolution. There are already groups—most notably the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs and the European Space Agency, who actively track statistics related to space debris—attempting to address this issue in structured ways. Traditionally-confrontational parties could actively support these existing efforts without major political protest to build people-to-people rapport. NASA is already looking into the issue, having most recently released the first detailed cost-benefit analysis on space debris in March 2023, while CNSA has been launching satellites specifically related to space debris monitoring since at least 2015.

Also, the alarm going off in February 2024 of Russia potentially building nuclear-connected anti-satellite missiles—or the report of North Korea’s first successful spy satellite—have garnered deep concerns and should be seen as points of overlapping interest. It is not logical for the U.S. or China to allow a nuclear war or espionage. Admittedly, approaching this avenue would be far more complex, given the United States’ skepticism of China-Russia relations; a perspective that Beijing condemns as disinformation. As recently as January 2024, China responded in a daily news briefing to recent U.S. descriptions of outer space as a “battlefield” and of China and Russia developing anti-satellite weapons, calling such descriptions a provocation of a major-power rivalry and disinformation born to excuse militarization. One month later, a senior intelligence chief in the U.S. Space Force directly advised the international community against conducting commercial space business with Beijing and the Chinese Communist Party because they are already “rapidly expanding launch capabilities…[and] expanding beyond their national spaceports.” Given the strong rhetoric flowing between Beijing and Washington—the strength of which cannot be expected to wane in a U.S. general election year—such anti-nuclear collaboration seems far unlikely. Does that low likelihood mean that the door to such collaboration should be automatically closed? No, it does not.

Lastly, law in and of itself is also an increasingly popularized term in association with outer space, Beijing regularly expresses interest in formalizing and then abiding by international legislation of some sort on outer space. One August 2023 report from the United States Institute of Peace directly references Chinese planners’ interest in “legal warfare” as part of a larger strategy.

Even more than the historically high levels of mutual distrust, the 2011 U.S. Wolf Amendment is the single most important barrier to U.S.-China cooperation in space. In short, this law forbids NASA from cooperating with its Chinese counterparts without prior authorization from both the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the U.S. Congress. Furthermore, it “does not effectively do its job of preventing technology transfers with China and instead encourages distrust with no real benefit to the United States.” First and foremost, if there is any desire at all for rapport to be reestablished between these two nations on this front, this law needs to be reevaluated and addressed, ideally by a dedicated working group.

Even while keeping these points in mind, it still currently appears to at least this one observer that the U.S. could do more to keep itself not only relevant but a leader in space as China expands its diplomatic inroads on space. Imminent improvement is not only possible but necessary. If the leaders in U.S. space policy are not already conducting such moves with intentionality and lasting vigor, they very well may be running out of time to keep the United States’ voice relevant in the space realm as new parties join the playing field and China diligently cultivates resilient connections.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2024 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

How Ukraine war and sanctions on Russia put Arctic cooperation on ice