Cover Image Source: Getty Images

Adjunct Fellow, Trade 'n Technology Program

China’s recent spate of technology regulations includes an anti-trust probe into Alibaba and other firms, suspension of Ant Group’s IPO, revised rules authorizing the increased protection of data, restrictions on education technology and food delivery companies, and restrictions on the use of algorithms.

While the specific reasons for the crackdown are not known, it is speculated that they have been carried out to curb illegal activity, guarantee national security, and ensure “common prosperity.” China may also be attempting to redirect its economy toward strategic industries or, alternatively, Chinese regulators could be battling over turf.

The regulations have imposed short-term costs under the promise of long-term stability. They have also created an atmosphere of uncertainty for American investors against a backdrop of tightening U.S. rules against investment in Chinese firms. In particular, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has recently highlighted risks associated with possibly faulty Chinese firm disclosures.

U.S. investors were already wary of China’s overseas listing structures which are known as Variable Interest Entities (VIEs). These structures were created by non-government actors to allow Chinese firms in sensitive industries to obtain foreign investment, even though such structures are considered illegal in China. There are other U.S. investors though who view the regulatory assault and the ensuing downturn in tech stock prices as a buying opportunity.

China has initiated a Regulatory Five-Year Plan to increase regulation in the areas of “national security, technological innovation, public health, culture and education, ethnic, religion, biosecurity, ecological civilization, risk prevention, anti-monopoly, and foreign-related rule of law.” It is unclear how the new regulations and enforcement will be carried out. To the extent that the Regulatory Five-Year Plan dictates guidance by Communist Party ideology, the power of Big Tech in China will continue to be effectively reduced.

China’s technology-enabled digital sector has been a hotbed of activity over the past decade-and-a-half. Backed by a billion or so consumers, dynamic players such as Alibaba (ecommerce), Tencent (social media), Huawei (telecommunications), Baidu (search), and Hikvision (AI), among others, have blazed a trail of innovation and dynamism. In the financial services sector, two large Big Tech firms—Alibaba and Tencent—today account for the vast majority of the domestic mobile payments market as well as host of other services, such as digital credit. The rapid growth, size, and disruptive presence of China’s digital sector has also invited the attention of the Party as well as regulators of late, with the two aiming to balance competing public policy objectives such as innovation and efficiency with social control, market stability, data privacy and consumer protection.

China’s blossoming internet era, which spawned a vibrant but veritable Wild West technology sector, appears today to be drawing to a close. Over the past 12 months, there has been a pronounced crackdown on the technology industry with several notable, home-grown Big Tech firms being cut down to size. The regulatory reckoning began following a speech by Alibaba Group Holding founder Jack Ma at the Bund Summit in October 2020, where he criticized (financial) industry regulators. New rules arrived swiftly thereafter.

In November 2020, Ant Group’s monster IPO, reportedly valued at $200 billion, was suspended and Ant was later required to form a financial holding company overseen by regulators. Ant was also required to break its “information monopoly” over data collection. China’s State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) examined whether Alibaba had engaged in practices that obligated sellers to sign exclusivity contracts.

In December 2020, the Export Control Law was implemented with a view to restrict the exports of goods and technologies related to national security. This law represents the first full framework for restricting exports of military and dual-use technologies and products. State Export Control Authorities will publish control lists that identify controlled items.

In March 2021, fines were levied by the State Administration for Market Regulation on 12 companies over anti-monopoly violations. The companies, including Baidu Inc., Tencent Holdings, Didi Chuxing, and SoftBank, were fined ¥500,000 ($77,000) each for not disclosing previous investments, acquisitions, or joint ventures.

In April 2021, Alibaba was fined $2.8 billion, and 34 technology firms were warned to curb excesses following an antitrust review. SAMR’s statement on Alibaba found that “since 2015, Alibaba Group has abused its dominant position in the market and has…prohibit[ed] merchants on the platform from opening stores or participating in promotional activities on other competitive platforms.” The 34 firms were required to correct anti-competitive practices within one month, over which time they had to carry out internal checks and inspections. Regulators also issued new IPO restrictions, following which 84 companies so far have withdrawn their applications.

Fintech companies were ordered to follow regulations, as 13 fintech companies were summoned by regulators. Fintech firms were warned to eliminate “improper” links between payment tools and other financial products, eradicate data holding monopolies, and prevent risks associated with internet mutual aid business.

In June 2021, China released the Data Security Law, which seeks to protect critical data to protect national security and the public interest. Data activities governed by the law include data collection, storage, usage, processing, transmission, provision, and the disclosure of data. The law classifies data into different types based on the level of importance. Data is placed in the categories of “important data” or “national core data” based on their relative importance. The law governs data both inside and outside of China that may threaten the country’s security interests.

In July 2021, food delivery platforms were brought within the regulatory net, resulting in a 14% plunge in the stock of Meituan. Guidelines issued by the State Administration for Market Regulation and six other administrative departments required delivery platforms to improve pay, provide insurance, and relax delivery deadlines. In August, platforms were called into a meeting with government regulators to discuss improvements in raising the quality of safety and labor rights for delivery workers.

The next target of regulation was education technology companies, which faced restrictions on for-profit tutoring services focused on China’s core curriculum or high school and university entrance exams. China’s “double reduction” policy sought to reduce homework and after-school study hours. New private tutoring firms were banned from registering, and existing online education companies were required to seek new approval. Some newly public firms were also probed. These included truck-hailing app Full Truck Alliance Co. and online recruiting app Kanzhun Ltd.

Tencent also fell under the spotlight and it was ordered to give up exclusive music licensing rights. The State Administration for Market Regulation fined the company ¥500,000 ($77,141) due to violations in its acquisition of China Music in 2016. This acquisition had resulted in market ownership by Tencent of over 80% of music library resources. Around the same time, the company suspended new registrations for WeChat to comply with regulations.

Also in July 2021, Didi, which had just been listed on the New York Stock Exchange, was forced to suspend signing up new users. The app was pulled from app stores in China over allegations that it had illegally collected personal data of its customers. Didi collects data on users, mapping and traffic and has asserted that it stores all of its user data in China rather than overseas. In its IPO prospectus, Didi had stated that “we follow strict procedures in collecting, transmitting, storing and using user data pursuant to our data security and privacy policies.” The suspension was a blow to American investors and added to their suspicion of Chinese firms’ overseas listings due to the sudden pre-IPO investigation of Ant Group, coupled with the Didi business suspension.

In a companion policy issued after the Didi debacle, technology companies were required to submit to a cybersecurity checkup before going public on overseas stock exchanges. Companies that possess data on over 1 million users must now seek cybersecurity approval before listing abroad, since the data leaves China vulnerable to malicious activities of foreign governments, according to the Cyberspace Administration of China. This regulation makes it more difficult for technology firms to raise funds abroad.

In August 2021, China cracked down on algorithms. Draft rules were laid out by the Cybersecurity Administration to control algorithms that recommend content to customers to increase the amount of time or money they spend by being directed to specific pages. The draft stated that firms may not implement algorithms that cause customer addiction or excessive spending. Violations of the law could result in fines of ¥5,000-¥30,000.

Also, in August 2021, China released its Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) which aims to protect citizens’ data. The law, while not preventing the Chinese government from accessing data on its people, does prevent firms from transferring personal data abroad. The PIPL was modeled after the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and focuses especially on apps that make use of personal information to target consumers and prevent such international transfer of personal information. Companies are only allowed to collect personal information for a clear and reasonable purpose and must disclose this to the consumer. The information must be handled in a way that does not infringe on consumers’ personal rights.

Most recently, the government has cracked down on online activity within China, reducing the number of hours that children under 18 are allowed to play online video games to three hours per week and banning online celebrity fan clubs. One party official stated that “protecting the physical and mental health of minors is related to the people’s vital interests, and relates to the cultivation of the younger generation in the era of national rejuvenation.” Gaming stocks, including those of Tencent, NetEase and Bilibili, have come under pressure as a result of the new regulation.

There are several reasons that have been advanced by the Chinese government for its regulatory crackdown on domestic Big Tech. These include curbing of illegal activity (as in anti-monopoly investigations), guaranteeing national security (as in the Export Control Law and Data Security Law), and protecting the people (as in the crackdown on education technology and algorithm control).

Curbing illegal activity. The reason that is easiest to legitimize is implementing regulation to curb illegal activity. Some activities include engaging in illegal insuretech business, harming the public by misusing funds and providing substandard services. The “Notice on Carrying out Special Rectification of Internet Insurance Disorders,” implemented on August 11, 2021, also sought to end bad practices, including improper marketing and pricing practices.

Guaranteeing national security is another commonly given reason for new regulations. China has become increasingly concerned about the security of its data. Going even further, Legarda (2021) has asserted that national security has become a top priority under Xi Jinping. This approach reflects the Party’s intervention against perceived threats to its power as well as the integration of development and security. China’s Communist Party views security as a necessary condition for development, and development as a requirement for security.

Outside observers have provided additional hypotheses for the implementation of new technology regulations. Such hypotheses range from the government’s need to consolidate power over the technology sector, backlash at overseas investors, to more humdrum arguments suggesting that such conduct is part of China’s normal regulatory pattern.

China’s new ideology of “common prosperity” has also been provided as a reason for implementing new regulations. It has been previously asserted that the Communist Party views regulation as a means to protect the common good, protect public stability and reduce inequality. Regulations, according to this view, have been put in place to protect the public. This ideology has also induced self-correcting behavior among Chinese billionaires and large firms. These firms and their wealthy leaders have scrambled to exemplify altruistic behavior by donating funds for COVID-19 relief and contributing to poverty alleviation. The founders of Meituan, Pinduoduo, Xiaomi Corp, and others have donated large amounts recently to social causes.

Some Chinese firms have attempted to ‘self-correct’ in order to stave off future regulatory surprises. For example, KE Holdings, China’s largest platform for matching buyers and sellers of real estate, shut down its VIP services which had hitherto committed to fast sales on exclusive listings. This came as the company was being investigated for antitrust violations. Tencent Holdings moved to restrict time that children spend on its most popular game, “Honor of Kings.” NetEase Music stated that it would not enter into exclusive contracts starting July 2021.

It has also been suggested that China’s regulations are part of its normal regulatory pattern; that the tech industry regulations are part of a normal pattern of cracking down on a sector after it has been allowed to grow for some time. This pattern was observable in China’s shadow banking sector, in which shadow banking was allowed to grow over a certain time period, then subjected to a number of stringent regulations that curbed risky practices that were viewed as a threat to the common good. The difference between the technology sector crackdown and the shadow banking crackdown is that regulations in the tech sector are coming from several regulators all at once and not just from one main regulator. Regulatory bodies, including the Cyberspace Administration of China, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, the State Administration for Market Regulation, and the China Securities Regulatory Commission are involved in China’s technology sector regulatory clampdown.

This type of sudden regulatory implementation imposes serious short-term costs under the promise of long-term stability. The goal of long-term stability and security in the tech sector has become increasingly important considering tensions between the U.S. and China, which have underscored the importance of technology and intellectual property security.

Yet, other explanations for the tech crackdown are that China is attempting to redirect its economy toward strategic industries or Chinese regulators might be engaged in turf battles. According to Li Chen, the chief economist at Soochow Securities, China may be reorienting its economy toward manufacturing and hard technology, such as semiconductors and industrial internet, and away from consumer internet. According to David Wertime of Protocol, Chinese regulators are engaged in a bureaucratic power-play by implementing their own tech regulations one after the other in a contest to see who can impose the strongest regulation.

The new technology regulations have impacted American investors. American investors are divided on how to view China’s clampdown on Big Tech. While some view the regulations as a sign that Beijing is cracking down on foreign investment, others see the slip in stock prices as a buying opportunity.

China’s new regulations have been strongly impactful, especially the anti-monopoly regulation of Alibaba and the data security and M&A investigation of Didi. In addition, since Ant Group and Didi were investigated immediately prior to or just after listing abroad, some U.S. investors have speculated that China’s government is attempting to curb overseas activity by Chinese firms.

U.S. investors have become jittery over the mounting costs imposed by China’s new regulations. The uncertainty created by the onslaught of regulations and the promise of future regulations has caused panic over Chinese overseas listings; especially since some of the regulations appear more tied to ideology than risk aversion. It has become clear that regulators are particularly focused on industries that are viewed as strategic and essential to social stability. The regulatory wave has underscored the fact that Chinese firms are strongly subject to the vagaries of government policy shifts.

Chinese tech regulations come at a time of heightened wariness in the U.S. regarding investing in Chinese firms and have exacerbated an already worsening situation. The backdrop to the tech regulatory crackdown is that the U.S. and China were in a trade war in which technology and associated intellectual property issues took center stage. Animosity between the two countries had grown since 2016, and the U.S. government as well as non-government experts encouraged increased scrutiny of Chinese firms, both before and during China’s technology crackdown.

Two specific issues that the U.S. government and the investment community have pointed to are:

First, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has highlighted risks associated with Chinese firm disclosures. The SEC has stated that China-based firms may provide investing disclosures that are incomplete or misleading. One of the biggest issues in provision of proper disclosures are China’s restrictions on the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board’s (PCAOB) ability to inspect audit work and practices of public accounting firms in China and Hong Kong. The PRC Securities Law, which went into effect in March 2020, even before the tech regulatory storm began, states that China can block overseas securities regulators from conducting investigations or collecting evidence related to the securities business without government approval.

The SEC is considering a new standard that would disqualify audit work by accounting firms located in places such as China. This could result in delisting of Chinese firms from U.S. exchanges. The Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) has adopted this rule and sought the SEC’s approval to prohibit foreign businesses from U.S. exchanges under the Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act. The PCAOB currently has the power to delist firms from U.S. exchanges if it is not allowed to properly inspect audit work papers for three years in a row.

Second, U.S. investors were already wary of China’s overseas listing structures, known as Variable Interest Entities (VIEs). Such structures were created by non-government actors to allow Chinese firms in sensitive industries to obtain foreign investment. In this scenario, China-based issuers form non-Chinese holding companies that are contractually tied to the Chinese operating companies. This is a contractual arrangement rather than direct ownership, which foreign investors view as riskier since they may have to incur significant costs in order to enforce the investment arrangement. The VIE structure has been used in the internet and data industries, and has been applied to most overseas listings, including that of Alibaba, JD.com, and Tencent.

However, the VIE structure is illegal in China and now China’s regulators are reviewing the structure. The China Securities Regulatory Commission has likely been scrutinizing firms that seek to list abroad (such as Ant Group and Didi) using the VIE structure. China’s Ministry of Commerce laid out a regulation in 2015 that stated that VIEs were acceptable if the foreign-registered shell company was controlled by Chinese investors. Concerns over monopoly activity by some overseas-listed firms has once again drawn attention to these structures.

The new regulations, coupled with mounting U.S. investor and regulatory wariness of Chinese firms, have induced some commentators to altogether reject investment in Chinese stocks. Jim Cramer, host of Mad Money on CNBC, stated ““I am done. I am not touching any of these…Chinese stocks. You can’t.” Others, though, from small traders to large market players such as Blackrock, view Chinese stocks as a bargain. Blackrock analysts have stated that “investors are compensated for risk at current valuations in our view.” Which of these views is most accurate will be borne out by future regulatory actions, which are anticipated to occur over the next five years.

China has initiated a Regulatory Five-Year Plan which states China will “actively promote legislation in important areas such as national security, technological innovation, public health, culture and education, ethnic religion, biosecurity, ecological civilization, risk prevention, anti-monopoly, and foreign-related rule of law.” The plan aims to enhance law enforcement and ensure that administrative agencies serve the people.

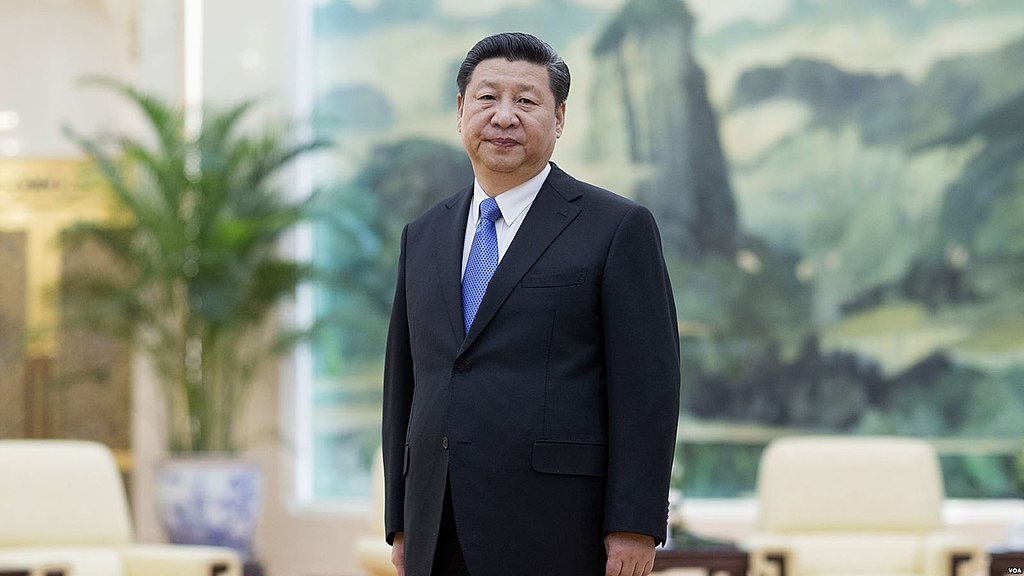

However, to the extent that the Regulatory Five-Year Plan dictates guidance by ideology, it is somewhat unclear how these new regulations and enforcement thereof will be carried out. The first point commits to the “in-depth study and implementation of Xi Jinping’s thoughts on the rule of law,” which refers to Xi Jinping’s writings and speeches that mention the topic. This was laid out at the first Central Conference on Work Related to Law-Based Governance in November 2020, where President Xi emphasized the need to focus on the people, to uphold Constitution-based governance, and to commit to the socialist rule of law with Chinese characteristics.

While the new plan appears to aim at making government more efficient and create a fair and stable business environment, it is not clear how Communist ideology will impact the types of rules to be created and enforced. Like Xi Jinping, the party is a living, breathing entity that takes a different view of how a government should be run compared to its Western counterparts. This is evidenced in the types of new technology regulations that China has recently laid out, particularly regulations that attempt to curb social behavior. Therefore, while we can expect that China will increase the number and enforcement of regulations, particularly in the tech sector, we do not know exactly what types of regulations will become a focus in the near future.

We can only speculate that China will follow its current trajectory of tech-related regulations, implementing new rules that effectively reduce the power of its home-grown Big Tech firms. China also tends to favor domestic over international investors, and the concern that China has been seeking to crack down on the VIE structure has led the U.S. SEC to warn American investors over the riskiness of investing in Chinese stocks.

In addition, while China has committed to expanding innovation, we now know as a result of these new regulations that innovations must have their own built-in guardrails. In other words, innovations must be mindful of following ever-evolving Communist Party dictum and best practices. Innovations should serve the people and the Party when everything is taken into consideration. What precisely that means is unclear but is likely to become somewhat more intelligible over time.

So, what can one expect for the future? More regulations—especially rules that coincide with high-level political objectives and directives over time as well as those that reduce socioeconomic instability. We also expect more enforcement of existing regulations across industries and more activity by SAMR on anti-monopoly activity. The swathe of new regulations and the Regulatory Five-Year Plan are a call to arms by Chinese regulators. As such, U.S. investors should study these regulatory plans carefully to reduce uncertainty.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2025 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.