Research Associate & Administrative Assistant

Cover Image: The first domestically-made aircraft carrier of the Chinese Navy under construction, 17 June 2019. (Source: Wikipedia Commons, CC-BY-SA-4.0, Tyg728)

With the novel coronavirus pandemic ravaging lives and livelihoods , U.S-China strategic competition continues to evolve in the realms of security, trade, technology, and global influence and authority. Despite the pandemic’s clearly intensifying effect, the bilateral relationship between the United States and China has continued to deteriorate across a range of issue areas under the context of renewed great power competition.

The coronavirus pandemic has accelerated and intensified certain frictions that were already in place due to increasing levels of strategic competition. The ‘blame game’ throughout the pandemic has merely shed more light on the already deepened mistrust between the two countries, which has exacerbated the hostile and confrontational approaches at both ends.

Tensions in the Western Pacific continue to rise as both China and the U.S. ramp up military activity in the region. Trade negotiations between China and the U.S. are threatened by the economic recession and the deepening frictions between the two countries during the pandemic. U.S.-China technological competition over Huawei and 5G has remained consistent as it was before the pandemic. Both the United States and China have not been successful in winning over the hearts and minds of the international community as a leading global great power. Adding to this, neither country has been able to lead the world by themselves during the COVID-19 crisis, as the rest of the world hoped and expected.

Bearing in mind the context of intensifying U.S.-China great power competition, with the pandemic as an accelerator of tensions, some of the upcoming globally significant events, such as Tsai Ing-Wen’s inauguration and the Presidential and Senatorial elections in the United States, could echo the mistrust on display during the coronavirus crisis. Tensions will further rise between the United States and China, including in the Western Pacific theater.

The novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has dominated news headlines throughout the first half of this year. So far, over 4 million cases and 300,000 deaths have been confirmed worldwide. The pandemic also threatens to thrust the global economy into recession. The International Monetary Funds projected that advanced and developing economies will suffer a 6.1% and 1.0% average decline in real GDP respectively. World leaders, such as French President Emmanuel Macron, have called for a united global response amid the health and economic damages brought about by the disease. The world’s two largest economies, the United States and China, however, are not in a mood of cooperation with each other. While the world at large remains on pause due to the epidemic, the strategic competition between China and the U.S. continues to intensify. The two countries have engaged in a war of words over the pandemic. The U.S. accused China of a lack of transparency and, for a long period of time, claiming that the virus originated from a Chinese lab in Wuhan (this claim was just recently downplayed by the Trump administration). China, on the other hand, reacted strongly against what it describes as the “24 lies” coming out of the U.S., and a few of its diplomats suggested that the virus was brought by the U.S. military to Wuhan.

Besides the words that fueled furious exchanges between the two countries, however, were real actions taken by both sides during the pandemic that continue to intensify the competition between China and the U.S. on multiple fronts – Security, Economic and Trade, Technology, and Global Leadership and Influence. Strategic competition between China and the U.S. in these realms was either emerging or underway prior to the COVID-19 epidemic. The coronavirus pandemic has provided additional context to the increased competition in each of these areas Although global headlines are rightfully captivated by the pandemic, it is necessary to follow developments in these realms in order to sustain a big-picture understanding of the ongoing great power competition between the U.S. and China. Furthermore, as the second half of 2020 approaches, it is worth keeping in mind other upcoming internationally significant events that could further complicate the U.S.-China bilateral relationship.

In the short-term, the coronavirus is intensifying tensions between the U.S. and China. In the long-term, however, both sides are steadily taking a tougher stance towards each other as a result of the renewed great power competition. That being said, the coronavirus has accelerated confrontations between China and the U.S. in competitive areas defined by the United States.

The United States reintroduced the concept of the “renewed great power competition” in the Obama Administration’s June 2015 National Military Strategy. It was more fully focused upon in the Trump Administration’s December 2017 National Security Strategy (NSS) and January 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS), which “formally reoriented U.S. national security strategy and U.S. defense strategy toward an explicit primary focus on great power competition with China and Russia.” Despite such an account, the 2015 National Military Strategy did not use the phrase “great power competition” to characterize the United States’ relationship with China. However, it did characterize China as one of the countries that “are attempting to revise key aspects of the international order and are acting in a manner that threatens our [the U.S.] national security interests.” By then, the term was still mainly focused on security-related matters, until it was expanded beyond its original scope by the Trump administration.

The Trump administration made it clear that bilateral competition with China and Russia is not limited to just military matters, but also for economic, technological, and even competition for global influence. Although the 2017 National Security Strategy Emphasized that “competition does not always mean hostility, nor does it inevitably lead to conflict”, it did acknowledge that the notion of competition had trickled into virtually every area involving both the U.S. and China. Moreover, to put aside whether the U.S. took the optimal stance managing its relations with China, the continuation of the notion of “renewed great power competition,” birthed by the Obama administration, is a primary guiding theme of the American approach to China in forthcoming years.

Beijing has not officially acknowledged the notion of “renewed great power competition.” As a rising global power, China’s rhetoric focuses on sustaining and enhancing its internal growth to realize a “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” This great rejuvenation has been the governing philosophy of the Communist Party of China since its introduction by then-President Jiang Zemin at the 16th Party Congress (2002). Jiang called for the party to take a firm grip on development that makes the country strong and the people rich. In his report at the 19th Party Congress in 2017, Chinese President Xi Jinping capitalized on this phrase to express two goals: 1) by 2035 China’s economic and technological strength will increase significantly and China will become a global leader in innovation and; 2) by 2050 China will become a global leader in terms of composite national strength and international influence, with a people’s armed forces that have been fully transformed into world-class forces. This latest interpretation of the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” has made it clear that China seeks to become one of the leading countries on the global stage. This inherently affects the United States’ current position in the world and, subsequently, the bilateral relationship between the U.S. and China.

Concurrently, China’s attitude to its interaction with the United States has also evolved during the second decade of the 21st century. While visiting Berlin in 2014, Xi Jinping popularized that the Chinese people “do not make trouble, but have no fear of trouble.” Following President Xi’s example, officials from the Ministries of Foreign Affairs, Commerce, and National Defense utilize this rhetoric when addressing China’s position during recent events, such as the trade war, U.S. freedom of navigation operations (FONOPS) in the South China Sea, and addressing the controversies over the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Historically, this is a major shift away from Deng Xiaoping’s 12-character guiding principle for internal and foreign policies that emphasized “hide our capacities and bide our time,” and, via many recent incidents, made it clear how China would respond to U.S. policies conducted under the notion of renewed great power competition. However, competition does not inherently involve hostility; if cooperation falls apart, both sides would at least seek to balance out each other in the powerplay.

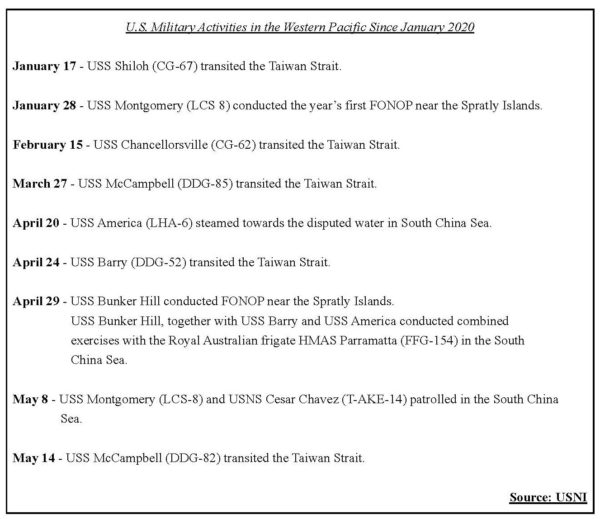

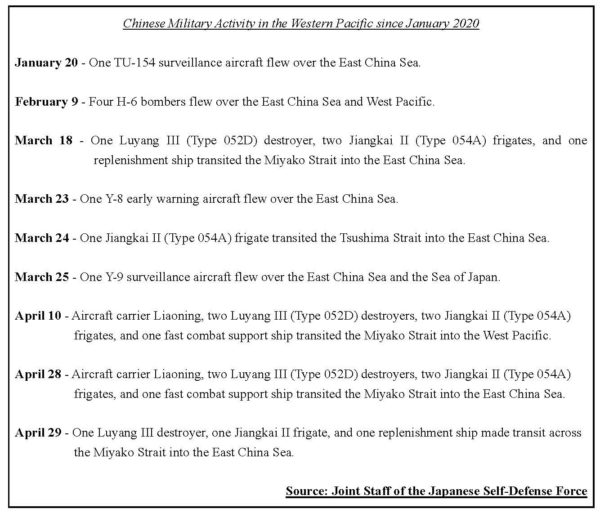

On the security front, U.S. military activities in the Western Pacific have continued despite reports of viral outbreaks aboard some of its warships in the region. Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPS) in the South China Sea and in the East China Sea, particularly in the Taiwan Strait, have continued as well. These actions triggered strong narratives from the Chinese side. On April 28, China’s Ministry of Defense claimed that China expelled USS Barry, which illegally entered China’s Xisha (Paracel Islands) territorial waters. In response, U.S. Defense Secretary Mark Esper criticized China of “not being consistent in how it follows international maritime norms.”

China also continued its military activities in the region, both in the South and East China Sea, and out into the Western Pacific Ocean, usually across the Miyako Strait or the Tsushima Strait. On April 18, China officially established the Xisha district under the governance structure of Sansha city, and explicitly includes the relevant features within the new district’s administrative purview. Latest report suggests that China has deployed early-warning aircraft, anti-submarine aircraft on the South China Sea’s Yongshu Reef (Fiery Cross Reef) amid increasing U.S. activity in the South China Sea.

Dynamics on the bilateral trade front between the two countries have been relatively quiet since the signing of the Phase 1 trade agreement in January. However, as the global economy continues to suffer under the pandemic, it remains unclear whether the two countries could continue their trade negotiations to resolve disputes as they agreed before the global outbreak. On a positive note, reports from Chinese media suggest that China would implement the trade deal regardless of the pandemic. On the negative side, however, due to the ongoing “war of words” between China and the United States, reports suggest that hawkish Chinese advisors are urging talks with the United States to negotiate a new trade deal. Moreover, on May 11, President Trump said he is “not interested” in reopening negotiations with China and is also considering abandoning the Phase 1 deal amid tensions with China.

In the realm of technology, the controversy over Huawei has deepened despite the pandemic. The U.S. declared the Chinese tech giant a threat to U.S. national security and moved to ban Huawei from selling products to the U.S.. China, on the other hand, called actions taken by the U.S. “unreasonable suppression”. Huawei has been a key issue of U.S.-China technology competition for a rather long time. On February 13, the U.S. expanded its lawsuit against Huawei, accusing the tech company of a “decade-long” plan to steal technology from U.S. firms. Around the same time, U.S. defense secretary Mark Esper warned U.S. alliances and the future of NATO will be threatened if they include Huawei equipment in their 5G networks. Lawsuits and blacklisting led to a USD 12 billion shortfall in revenue, even though the company still reported a profit growth of 19.1%.

The targeting against Huawei has further raised tension between the two countries, and the U.S. appears to be very determined on this issue. Attorney General William Barr addressed the Huawei issue in early February and emphasized the connection between U.S. national interests and 5G:

Within the next five years, 5G global territory and application dominance will be determined. The question is whether, within this window, the United States and our allies can mount sufficient competition to Huawei to retain and capture enough market share to sustain the kind of long-term and robust competitive position necessary to avoid surrendering dominance to China. The time is very short, and we and our allies have to act quickly.

Attorney General William Barr

Under such pressure from the U.S., during the release of Huawei’s 2019 annual report, Huawei Chairman Eric Xu warned that “[t]he Chinese government will not just stand by and watch Huawei be slaughtered on the chopping board.” On May 16, just a day after the United States decided to cut Huawei off from global chip suppliers, China’s Ministry of Commerce warned that “China would take all necessary measures to safeguard the legitimate rights of Chinese enterprises.”

In the realm of global influence and leadership too, the United States and China continue to compete with each other. The U.S., under President Trump’s “America First” policy, is exacerbating relationships with some of the international organizations that were once established under the liberal world order backed by the U.S., such as the World Health Organization (WHO). Accusing the WHO’s poor handling of the global coronavirus outbreak, and the issues related to its apparent complacency with China’s transparency issues, President Trump pulled U.S. funding of the WHO on April 14. Meanwhile, the United States’ own global leadership standing has been called into question, such as when the U.S. government was accused of (and denied) diverting a shipment of masks which was due to arrive in Germany.

China has increased its effort to build its image as a “responsible great power”, yet the international response has been mixed. On one hand, China has been eagerly pushing for multilateral cooperation combating COVID-19 under its frequently promoted idea of “a Community of Share Future for Mankind”. After containing what is hoped to be the first and only wave of the epidemic within its borders, China has been sending medical supplies abroad. The United States was also among countries that accepted Chinese masks. However, on May 7, the Food and Drug Administration withdrew approval for manufacturers in China to export N95-style masks to the U.S. due to quality issues. Similar issues transpired with the European Union, which suspended delivery of 10 million Chinese masks due to quality complaints. Furthermore, due to the global shortage of medical supplies, China’s central role in the supply chain is also being questioned by U.S. policymakers. It was reported that the Department of Homeland Security accused China of intentionally delaying reporting to the World Health Organization about the pandemic while stockpiling crucial medical supplies and slashing exports of surgical face masks and other items needed to respond to the pandemic. China did not acknowledge the accusation. Some observers also criticized China for implementing a so-called “mask diplomacy”, which deploys a combination of medical supplies and financial aid that enables Beijing to project its power abroad as a public relations campaign, mostly in parts of Europe that have suffered deeply from the virus’ outbreak.

As the U.S. seeks to hold China accountable for the losses caused by the coronavirus outbreak and face strong opposition from the latter, President Trump made a strong comment suggesting that the U.S. “could cut off the whole relationship” with China. China has been using the pandemic to attack the U.S. with some of the accusations the U.S. has made about China before, such as the human rights issues. As hostility rises between the two countries, to some observers, the “international political landscape will totally change.” Before the epidemic, most of the great power competition between China and the United States has been in the realm of trade and technology, such as the Trade War and controversy over Huawei.

This epidemic could intensify the sense of insecurity of both sides, which could further accelerate the pace of military competition in the Western Pacific. Both countries will face domestic pressure after the epidemic and they cannot appear weak on these and other matters.

While the pandemic will eventually recede, actions in these areas have left a strong impact that will echo in the future through the deepening mistrust between the two countries. Therefore, events and key issues that began to emerge during the pandemic are also worth tracking. The Presidential and Senatorial elections of the United States will be some of the most important influencing factors in the second half of 2020. However, due to the pandemic, so far there has been very little campaigning compared to previous elections. It was reported that the Senate Republican candidates were given advice to attack China aggressively when addressing the coronavirus crisis during the election. Democrats have not held back on issues related to China as well. The current administration’s handling of the pandemic and the U.S.-China issue will become hot topics for debate and discussion during the elections.

Taiwan’s current administration has already been in the hotspot during the pandemic. For instance, Taiwan has been lobbying to take part as an observer in the WHO’s decision-making body. However, Beijing has raised strong objections due to its “One China” principle. A report published by the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission suggested that Beijing’s influence within the WHO and its pressure on the UN agency to exclude Taiwan could undermine global health. Meanwhile, the report also accuses Beijing of ramping up military pressure on Taiwan through coercive actions. The fragile relationship across the strait could worsen as Taiwan’s president-elect Tsai Ing-Wen will be sworn into office on May 20. Given her pro-independence leanings and anti-China position, the tensions across the Taiwan Strait could further rise in the forthcoming months. An exclusive report by Japan’s Kyodo News recently suggested that China would likely hold military drills in August near Hainan Island in the South China Sea. The report suggests that the military drill would focus on amphibious operations that trains the military to take over disputed Dongsha/Pratas Island, which is currently under Taiwan’s control. Meanwhile, on May 11, China announced that it will hold a 2-month-long military drill in the Bohai Bay. Given Tsai Ing-Wen’s inauguration on May 20, the timing of the drill increases tensions in the region.

The ongoing novel coronavirus pandemic has intensified frictions between China and the United States and added to the fragility of bilateral ties. Some observers are already worrying that a decoupling could finally happen due to the huge economic and political split created by the pandemic. Regarding the decoupling of the economy, there are analyses arguing that the pandemic has accelerated the speed of factories moving out of China. Regarding the political decoupling, some cite the historical analogy of the U.S.-Japan relationship in the 1930s, and have suggested that the economic decoupling could eventually lead to war between the two great powers.

The COVID-19 pandemic injected greater elements of competition into the U.S.-China bilateral relationship. However, the bilateral relationship is global, which means both countries are more integrated into the international system. This means that the interaction between the two countries is no longer the only factor that determines the outlook of the bilateral relationship. Any third party, particularly a bloc of countries as economically significant as the European Union, and its interactions with either China or the U.S. could pose a significant impact to the relationship as well. While some tensions between the two countries were sparked by the pandemic, the rest of the world still prefers an interdependent world system. Some countries have made it clear that they do not want to pick a side between China and the United States. Though the pandemic has worsened the bilateral relationship, it also sparked overwhelming support for international cooperation in some major areas. When the pandemic eventually recedes, the internal pulse of decoupling and the external pressure to cooperate will coexist within the bilateral relationship between China and the United States, which could lead to an unprecedented form of bilateral cooperation as well as competition unseen in recent international relations history.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2025 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Opinion | As China modernises its navy, the US races to stay ahead