On October 11, 2023, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) held a virtual event to discuss how both the U.S. and European countries are responding to and understanding ‘de-risking’ between China and foreign countries. Titled Chinese Assessments of De-risking, the goal of the event was to provide a broader perspective on issues surrounding the de-risking of both government and private entities with China. As the U.S. and European countries shift their China strategy from de-coupling to de-risking, various uncertainties plague entities operating in the China sphere. Two panelists joined the event: Janka Oertel, director of the Asia program and senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, and Andrew Polk, non-resident senior associate and Freeman Chair in China Studies at CSIS. Lily McElwee, a fellow with the Freeman Chair in China Studies, moderated the event.

Providing two perspectives from different geopolitical spheres, the panelists both discussed the issues surrounding de-risking from their individual regional perspectives. Andrew Polk started off the discussion with a three-pronged explanation of the current situation in the United States. Firstly, there has been a rhetorical shift in the U.S. from the use of ‘decoupling’ to the term ‘de-risking’. As a result, U.S. policies have become more sophisticated. The U.S. government wants to “appeal to constituencies within Europe and the U.S. about what we mean exactly,” as use of the phrase ‘de-risk’ in lieu of decoupling frames the current situation more so in terms of national security. Secondly, Polk painted the picture of how Chinese analysts differ in their opinions on the de-risking shift from those in the government. There is “recognition in China among researchers and others that U.S. policy is becoming more sophisticated,” just as American researchers believe. In fact, “Chinese analysts [themselves] have a sophisticated understanding [of the shift to de-risk].” However, Chinese officials believe that “words don’t matter.” To them, American policy remains the same, so the change is not only rhetorical, but ironic as well. Thirdly, private corporations in the Sino-American sphere have “embraced the idea of de-risking, are looking to define what it means and to action them in the Chinese market.”

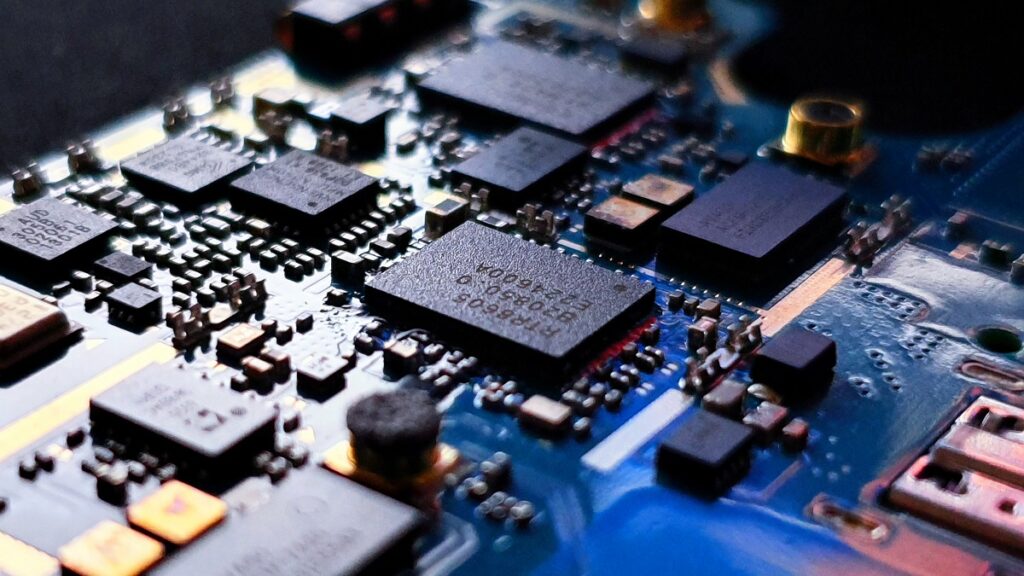

Janka Oertel provided the European perspective on the situation. To many Europeans, this terminology has been both helpful and hurtful. To them, “neither Chinese researchers nor the government want to be de-risked,” so European and American attempts to de-risk actually “runs counter to [both] Chinese interest…[and] to their own de-risking strategies.” For Europeans, according to Oertel, de-risking is a logical problem, as there is an actual tradeoff for entities. The de-risking has produced a “call for clarity in the messaging by those who normally master this in their [own] strategy,” said in reference to China. Additionally, for most entities in play, the de-risking strategy is about a competition. However, this is an alien concept to Europeans, who find the strategic competition narrative at large uncomfortable. The situation “is much wider than just where do we get critical materials from in the future to build semiconductors.”

Polk then went on to describe how a de-risking strategy may be implemented in the U.S. The issue, he argues, is that the American government “doesn’t necessarily understand or has articulated that they understand the challenges presented.” Thus, only “companies on an individual basis will be able to achieve [de-risking].” Since each company has a different plan on how to respond, at the individual entity level they can in fact be quite successful at de-risking. This is “more of a grassroots up development rather than a strategic clear pathway,” Polk elaborated. Of course, companies struggle to implement their own plans as “the reality is there is less of a voice for businesses in China policy.” To the U.S. government, “national security now trumps business goals in a very significant way.”

Following Polk’s comments, Oertel again provided the European context for the same dilemma that European private corporations are facing. For companies, “it was always risky to do business without any political backing,” but this time the situation is worse as “governments are no longer willing to take political risks [for companies].” Oertel does believe that this is a slight bluff on the governments’ side. After all, if a major German company is going to go down, the German government cannot sit by and watch tens of thousands of Germans lose their jobs. Finally, a unique issue facing Europe is that they “have to make sure there is no dissonance between all the countries in the European Union.”

To start the open discussion time, moderator Lily McElwee asked the following questions: “What countermeasures are Chinese analysts suggesting for Beijing? What direction is the policy heading?” Polk responded that the Chinese are employing a little bit of every strategy, which he said is a technique unique to China. Overall, however, “the trend has been to invest in the domestic production sphere more.” Polk believes that, for China, the only way out of the situation is for them to develop their own innovations. Oertel added that the Europeans believe that if they do not provide China with certain technologies, then China will develop them domestically anyway. However, if Europe does give in to Chinese demands, then they will develop domestic technologies faster with the additional outside help. To end, Oertel concluded that the “Chinese are very clear about the endgame,” which is to have a robust domestic market.

To conclude, McElwee questioned the panelists on what policymakers should be thinking about in order to reduce economic competitiveness. Oertel said that European countries are asking themselves questions like: “What are things to import from China that can solve derisking?” In other words, what can they source from another country, or what they can source from China without exacerbating the situation? They worry that the “Chinese government has a number of tools at hand to make de-risking a lot less attractive to companies.” This issue is also specific to Germany, which has many corporations that operate largely in China, such as many auto manufacturers. Polk answered that Americans need to switch their focus to corporations, to identify what they can and cannot de-risk. While the U.S. has not clearly defined the line yet, at some point they will have to do just that.