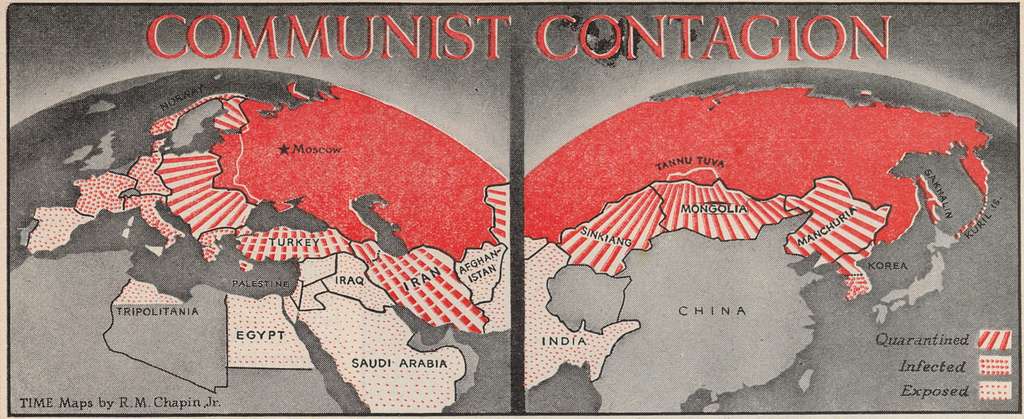

Cover Image: A map illustration of the “Two Worlds” of 1950 by Robert M. Chapin. (Source: manhhai via Flickr, CC2.0)

This piece was also released on Asia Times and, in a shorter form, on East Asia Forum.

Resident Senior Fellow

75 years ago this month, the American diplomat George Kennan published an essay in Foreign Affairs titled “The Sources of Soviet Conduct” in which he introduced the strategy of ‘containment’ to the Western world. Kennan advocated the firm containment of Soviet expansionism, which was being advanced under the banner of communism, at every critical strongpoint at which it encroached upon the interests of a peaceful and stable world order.

Kennan’s advocacy of containment was based on his reading of the philosophical drivers of the Soviet Union’s postwar foreign policy worldview. Moscow viewed the capitalist system of production to be nefarious and exploitative, as innately antagonistic to socialism, and in need of destruction as a rival center of ideological authority and geopolitical competition.

The China Challenge today is vastly unalike that posed by the early Cold War era Soviet Union that Kennan had surveyed. The Party’s ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’ aims to take advantage of capitalism’s strength as a means of resource allocation and efficient market exchange – not its supposed weaknesses of class conflict and violent spillovers. Besides, Chinese socialism is not an instrument of geopolitical aggrandizement.

More to the point, Kennan’s strategy of containment was premised on Washington remaining the dominant global economic power and using this abundance, and leverage, to exert collective discipline among the West in its dealings with Moscow. In China, by contrast, it will face a peer whose economic size and material capabilities at the government’s disposal will outstrip that of the United States. This will heap a collective action problem of the first order on the West. It will also test a core proposition on which U.S. primacy has rested: that America could meet the strategic challenge of the day from a position of national strength.

From an Indo-Pacific systemic perspective, the currency of competition in the age of the China Challenge will primarily be economic and technological, and less military or ideological. The gravitational pull of China’s domestic market will dictate that Washington embrace a light touch approach when crafting selectively decoupled supply chain strategies. Allies must be treated as co-equals; not appendages leashed to the immediate American economic self-interest.

Interminable maritime and military competition within the first and second island chains of the western Pacific will remain an inescapable feature of U.S.-China relations. Taiwan, in particular, will remain a powder keg for the foreseeable future. By the same token, there is no reasonable basis for an armed U.S.-China conflict to spill over into geographies that Beijing deems as lying beyond the anti-access, area-denial range essential for its prosecution of a first island chain-specific contingency. The Indian Ocean and the south Pacific will remain as sideshows.

75 years ago this month, the American diplomat George Kennan published an essay in Foreign Affairs under the pseudonym “X” titled “The Sources of Soviet Conduct.” Kennan, a Sovietologist, was at the time coming off a stint as charge d’affaires at the U.S. embassy in Moscow. In the essay, Kennan surveyed the political personality of Soviet power and based on his deduction of the philosophical drivers of the Soviet foreign policy worldview, tendered a number of practical suggestions for future U.S. policy towards Russia. The article struck an instant chord in Washington, D.C., grappling as it was at the time to come to terms with the Soviets’ intransigent ways in the immediate aftermath of World War II. The postwar final settlement in Europe had not yet materialized. Rather than engage constructively in East-West negotiations, Soviet leaders seemed more interested however in transforming their Central and Eastern European military occupation into a network of satellite regimes – first by co-optation of the region’s noncommunist parties, next by engineering coup d’états, and finally through outright suppression. Kennan provided a compelling exposition of the wellsprings of this alarming behavior on Moscow’s part.

“The Sources of Soviet Conduct” expanded on the ideas that George Kennan had expressed a year earlier in a confidential telegram to his State Department superiors, famously known as the Long Telegram. Drawing on the persistent caesaropapist impulses within the Imperial Russian tradition, Kennan portrayed the Stalinist dictatorship in the Long Telegram as simply the latest “of that long succession of cruel and wasteful Russian rulers who ha[d] relentlessly forced [their] country on to ever newer heights of military power in order to guarantee external security of their internally weak regimes”. With such an insecurity-ridden regime, “no permanent modus vivendi that [was] desirable and necessary” was possible, Kennan had averred. There was nary a mention of the word ‘containment’ in the Long Telegram. That word would enter the diplomatic lexicon for the first time in “The Sources of Soviet Conduct.” In the essay, Kennan counseled his countrymen to implement a policy of “long-term, patient but firm and vigilant containment” that was “designed to confront the Russians with unalterable counterforce at every point where they show signs of encroaching upon the interests of a peaceful and stable world”. “The Sources of Soviet Conduct” was not intended to be a comprehensive statement of national strategy; it nevertheless became one due to its rigor and timing, and the call to ‘containment’ effectively became the Western world’s geopolitical doctrine for the Cold War age.

75 years later, the rise of China and the deterioration of U.S.-China ties has spawned emulatory efforts to intellectually frame Washington’s adversarial terms of engagement – and disengagement – with Beijing during this first half of the 21st century. The most notable of these efforts has been a 72-page paper released by the Policy Planning Department of the Trump-era State Department in November 2020. Titled The Elements of the China Challenge, its key chapter delves into ‘The Intellectual Sources of China’s Conduct’. Like Kennan, the State Department paper purports to educate American citizens on the China Challenge at hand and instill an all-of-society response to prevail in the ensuing great power contest. Like Kennan, the State Department authors reach back to China’s pre-1911 imperial era behavioral drivers to explain the Chinese Communist Party’s conduct. “The defining component of China’s conduct” derives from the “CCP’s hyper-nationalist convictions” which are “not drawn from the Marxism-Leninism playbook” but from traditional Chinese thought as well as its 21st century model of authoritarian governance and international economic dependency-creation around the world, it postulates. Kennan had ascribed Soviet conduct to its despotic Tsarist inheritance too, with Marxism-Leninism more-or-less serving as a fig leaf of moral and intellectual respectability.

The State Department paper makes for interesting reading. It also invites a set of fundamental questions. Even if one accepts its framework linking persistent domestic behavioral drivers and Marxist-Leninist façade to external conduct on lines reminiscent of Kennan, is there much or any equivalence in the behavioral wellsprings of Stalinist Soviet Union’s conduct, then, and Socialist China’s conduct today? Don’t the domestic drivers of China’s external conduct, set against the Soviets’ conduct in response to ‘capitalist encirclement’ and geopolitical containment, point in fact to a very different set of outcomes? And which, in turn, should point towards a different set of ideas and strategy to cope with the China Challenge. Setting aside the argument that a policy of containing China might not be purpose-fit and implementable in the 21st century age of complex power distribution across interrelated policy domains, the China Challenge today is vastly unalike that scrutinized by Kennan, and it is instructive to compare the premises on which Kennan’s proposed policy of ‘containment’ was grounded.

In his reading of the basic features of the Soviet Union’s postwar outlook, George Kennan made three observations in “The Sources of Soviet Conduct.”

First, the leadership in Moscow viewed the capitalist system of production to be a nefarious and exploitative one. No “sincere assumption of community of aims” could be had with such a system; capitalism and socialism were innately antagonistic. And given capitalism’s hostile and incorrigible character, it was necessary to the contrary to engage in a patient but deadly struggle for its destruction as a rival center of ideological authority.

Second, the call for capitalism’s elimination notwithstanding, the Soviet Union was being threatened geopolitically by “antagonistic capitalist encirclement”. Caution, circumspection, flexibility and deception were hence the order of the day. Like the Church, there was no ideological compulsion for socialism to accomplish its purposes in a hurry. Rather, in the leadership’s view, “fluid and constant pressure to extend [the] limits of Russian [military and] police power [at home and abroad] … solemnly clothed in trappings of Marxism” needed to be exerted unceasingly to tip the balance of power in favor of socialist forces.

Finally, it was not a given that capitalism would perish of its internal convulsions, the rot within the system notwithstanding. It was necessary for the revolutionary proletariat movement to provide the final push that would tip the tottering structure over. For this to be the case, all good communists at home and abroad needed to fall in line and unswervingly abide by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union’s (CPSU) infallible leadership. Stalinist Russia would command; the satellites would conform and implement the party line.

So, how does the Communist Party of China (CPC) measure up today on these three points vis-à-vis its Soviet counterpart of yesteryears?

Kennan had ascribed the wellsprings of the Soviet Union’s zero-sum view to two interrelated factors: first, to the fundamental irreconcilability between socialism and capitalism, and second, to the traditional and instinctive sense of insecurity of the Russian people. In his Long Telegram, he had attributed this insecurity to that of a “peaceful agricultural people trying to live on vast exposed plain in neighborhood of fierce nomadic people … [and to which was added the] the fear of more competent, more powerful, more highly organized [Western] societies” with which it came into contact. “Unable to stand comparison or contact with political systems of Western countries” and fearing the ramifications of Russians’ exposure to their value systems, the Kremlin’s rulers had “learned to seek security only in patient but deadly struggle for total destruction of rival power, never in compacts and compromises with it”.

Setting aside the veracity of Kennan’s characterization, Chinese authorities too have faced their own millennia-long encounter with fierce steppe tribes on their periphery. The lessons they drew on and their response was altogether different – and revealing. Patient but total destruction of a fundamentally insatiable rival power was futile; it was cheaper and less destructive rather to turn their rivals’ avarice towards profit than war. The famous tribute system served, as one distinguished historian has described it, as an “institutionalized protection racket” by way of “which [the] Chinese traded[d] rich silks, porcelain, jewelry and money for bad horses, at a loss” in return for peaceful relations. Titles, subsidies and border markets were provided as per the dictates of power politics but always under the guise of a peerless emperor in exchange for secure frontiers. And it did not hurt either that the titles, subsidies and border markets munificently handed down embellished the local authority of individual tribal chiefs and preserved the fragmented political structure of the steppe. A modern version of this playbook is already evident in the Party’s economic dealings with various branches of the West.

As to the Soviets’ belief in the fundamental irreconcilability between socialism and capitalism, the Communist Party of China’s ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’ is aimed at taking advantage of capitalism’s strength as a means of resource allocation and efficient market exchange. It is not aimed at capitalizing on capitalism’s supposedly intrinsic class conflict or violent spillovers, as was the case in the mental world of the Soviet leadership. The Chinese economic model is itself called a ‘socialist market economy’ and features a hybrid public ownership economy and a non-public economy that are both important components of China’s ‘common prosperity’ agenda.

For Kennan, from the logic of the Soviets’ neurotic view of world affairs and the imperative for a “patient but deadly struggle for total destruction of rival power” stemmed the Kremlin’s need to continuously exert “fluid and constant pressure to extend [the] limits of Russian [military and] police power [at home and abroad]. For this to be the case though, Moscow had to first break out of the “antagonistic capitalist encirclement” that it was confronted with. The modus operandi was to be a persistent pattern of advance followed by semi-retreat, bred by a combination of appetite and risk aversion. The Kremlin’s political-military actions would be a “fluid stream” that would, if permitted, fill “every nook and cranny available to it in the basin of world power” – an unceasing constant pressure towards its desired ideological and geostrategic goal.

Granted, that the history of Chinese dynasties is littered too with constant skirmishing at shifting frontiers, which continues even today in a different form in the Himalayan borderlands and the South and East China Seas. But to what extent, if at all, is Kennan’s description of the Kremlin’s methods an apt representation of China’s tactics? Communist China has always been ‘Clausewitzian’ on territoriality-related considerations, treating physical pressure brought to bear, within limits, at the point of dispute as a continuation of politics and diplomacy by other means. Formal protests notes and demarches have been secondary to marking out its diplomatic position militarily on the ground. This coercive but limited use of force at expedient pressure points has oftentimes undermined its own interests. That said, these ‘gray zone’ episodes are driven by local factors and always linked to a larger calculus of territoriality and sovereignty; pertinently too, these episodes are not attached to an overarching or subversive ideology or strategic doctrine of conquest and domination.

More to the point, wizened by the ebb and flow of multiple Sinocentric orders assembled and dissipated, Beijing remains acutely aware of the limits of its power, not the power of its strength. Military means to exert pressure at distant locales with little relevance to territorial or core interests has never been, and will not be, a part of Beijing’s playbook. And indeed, during the 40 years of reform and opening-up dating back to 1980, no major or even limited war has been fought and a mere hundred-or-so lives in total have been lost in anger on China’s vast land and maritime frontiers. For what it is worth, it is also useful to note that the furthest extension of the Middle Kingdom’s territorial boundaries was effectuated by (non-Han) ‘conquest dynasties’, the Tang, Yuan and the Manchu, who in turn laid the foundations of a more variegated imperial strategic culture. Their Han Chinese successors, the Ming and the Chinese Communist Party today, typically set their eyes on consolidating, not extending, the inherited realm – a yearning that is most prominently in evidence today in the Taiwan Strait.

Finally, Kennan drew attention in “The Sources of Soviet Conduct” to Moscow’s implacable need for doctrinal fealty as it went about administering the final coup de grace to global capitalism. As that oasis of power which had been won for socialism, the Soviet Union’s infallibility as sole repository of the truth and guide of political action was to be unreservedly upheld within the global socialist movement. It was Kennan’s considered view that the Kremlin would “work toward destruction of all forms of personal independence, economic, political or moral [in Central and Eastern Europe … in order to bring the region] into complete dependence on higher [Moscow-directed] power.” The modus operandi of the reform era Communist Party of China bears little resemblance in this regard. The CPC does not export its ideology or subvert sitting governments. President Xi Jinping’s tendency to anoint the Party as the sole repository of the truth and thereby squelch justification for organized activity beyond its structures notwithstanding, Chinese socialism is not an instrument of geopolitical aggrandizement. The Party’s ideological evangelism stops at the water’s edge. The vaunted Belt and Road Initiative is not a mammoth ‘influence operation’ either that is intended to foster strategic dependencies (although it is understandable why it is viewed in that light). Like the United States’ own prodigious capital exports, a century earlier, it is geared rather towards recycling domestic surpluses into actionable projects that could enhance the productive capacity of recipient states on mutually advantageous terms.

More to the point, China owes its rise to the open, capitalist-led rules-based order. It sees no interest in cutting off its nose to spite an order that has held it, and could continue to hold it, in good stead over the next three decades of its unfinished national development. Indeed, Xi Jinping’s doctrinal framing of U.S.-China relations as ‘major power’ relations, not ‘great power’ relations, was intended to transcend age-old Great Power rivalry and hopefully presage a more peacefully coexistent dispensation. Rather than administer a final coup de grace to global capitalism, Beijing would prefer if anything to obtain the ‘keys to the kingdom’ than recreate the system anew.

In the concluding section of “The Sources of Soviet Conduct,” George Kennan argued that the risks of confronting the Soviet Union and increasing the strains under which it could be forced to operate was manageable from the standpoint of American policy. This was because the United States’ stake in the country was, as he had observed in his Long Telegram, “remarkably small”. America “ha[d] here no investments to guard, no actual trade to lose, virtually no citizens to protect, few cultural contacts to preserve…[the] only stake l[ay] in what we hope rather than what we have.” From this deduction followed Kennan’s exhortation that Soviet expansionism, advanced under the banner of communism, should be firmly contained at every critical strongpoint at which it encroached upon the interests of a peaceful and stable order. Further, the key global centers of industrial and military power must not be allowed to fall under rival control. Boxed within a limited geographic sphere of influence, the seeds of internal decay would in time “find their outlet in either the break-up or the gradual mellowing of Soviet power”. Tsarist rule too had collapsed after all, not due to external pressure or nationalism at the periphery, but due to disunity and revolt at the center.

Kennan’s observation of the United States’ “remarkably small” stake in the erstwhile Soviet Union bears (remarkably) little parallel to China today. U.S. exports to the mainland support over a million jobs, the stock of U.S. foreign direct investment in China exceeds $100 billion, annual overall bilateral trade exceeds half a trillion dollars, and American investors hold more than $1 trillion of Chinese equities. In the years ahead, these stakes will magnify as China becomes the largest economy in the world (at market prices) by 2030 and hosts the largest domestic consumption market by 2040. China’s demographic dividend might be approaching the point of exhaustion but there is as yet ample pent-up growth potential awaiting release in its on-going transitions from state to market and from rural to urban. And should the productivity level of Chinese workers in a couple of decades hence attain that of South Korean workers today, the Chinese economy could well swell to more than two-and-a-half times the size of the U.S. economy.

More to the point, Kennan’s proposed strategy of containment was premised on the United States remaining the dominant global economic power and using this abundance, and leverage, to exert collective discipline among the key Western centers of industrial and military power in their dealings with Moscow. In China, by contrast, it will face a peer that is without precedent in America’s brief but illustrious history – one who’s economic size and therefore the material capabilities at the government’s disposal will vastly outstrip that of the United States as far as the eye can see. This will, in turn, test a core strategic proposition on which U.S. primacy has rested since its international rise as a colossus at the turn of the 20th century: that America could meet the strategic challenge of the day from a position of national strength.

Several inferences follow from the standpoint of the U.S.’ China policy as well as the geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific, none of which point to containment as an apt choice.

First, American strategic conceptions to address the China Challenge must be based on realism and objectivity. Self-serving narratives, such as the United States and China being supposedly joined in a global contest between democracy and authoritarianism do worse than just deflect from the task at hand; they distort the forming of an accurate picture on the basis of which an evenhanded understanding of that country’s present course can be gleaned. No country is lining up at Beijing’s doorstep after all to imbibe the secrets of its Leninist political model. If anything, the ideas contest globally is one between a liberal and an illiberal version of capitalism. As Kennan had noted, the subject must be studied with the “same courage, detachment, objectivity, and same determination not to be emotionally provoked or unseated by it, with which [a] doctor studies an unruly and unreasonable individual”.

Next, American strategic conceptions must be endowed with an in-built mechanism of restraint and moderation. By training his focus on the villain of the piece, Soviet expansionism, and identifying communism principally as a justification for its expansion, Kennan released future U.S. strategists from having to chase the tail of communism in peripheral locations and guises under which it might appear. A similar limiting constraint that differentiates between ends sought and means applied by Beijing, and thereby facilitates a more focused application of American pressure against Chinese strategy must factor into Foggy Bottom’s thinking. This focused application of American diplomatic pressure must be anchored to international rules too. It is instructive that the beginning of the end of colonialism can be traced to that moment when the metropolitan power’s actions no longer measured up locally to the high-minded principles that it professed to be championing on behalf of its colony.

Third, the currency of competition in the age of the China Challenge will primarily be economic and technological, and less military or ideological. Military contestation is typically zero-sum; economic exchange inherently positive-sum. As China’s economic size outstrips its peers, the gravitational pull of its domestic market will heap a collective action problem of the first order on the United States and the West. Much like the Communist Party of China’s dynastic predecessors had sought to turn their steppe rivals’ avarice towards profit than war, and thereby also preserve their rivals fragmented political structure, the West’s collective action problem will paradoxically be exacerbated – not ameliorated – if Beijing embraces deeper reform of its industrial, investment and capital market regimes while appreciably reopening its civic society valve.

Fourth, the sheer size of the Chinese market will dictate that Washington embrace a light touch approach when crafting selectively decoupled supply chain strategies. An expansively drawn economic security perimeter that thwarts allies and partners’ advanced technology exchanges with Beijing could well turn out to be the 21st century’s geo-economic equivalent of the Maginot Line, leading potentially to the ‘designing out’ of U.S. parts and components from ensuing value chains. The essence of wisdom lies in organizing bespoke coalitions on building-block technologies, and thereafter ceding – not hoarding – economic decision-making power to allies and partners while maintaining overall convening authority. Allies must be treated more-or-less as co-equals; not appendages leashed to the immediate American economic self-interest.

Fifth, interminable maritime and military competition within the first and second island chains of the western Pacific will remain an inescapable feature of U.S.-China relations. In these waters, an immovable object – a core Chinese sovereignty interest – runs up against an unstoppable force – Washington’s abiding interest in navigational freedoms and its explicit and implicit forward-deployed alliance obligations. Taiwan stands at the geostrategic intersection of both and will remain a powder keg for the foreseeable future. By the same token, there is no reasonable basis for an armed U.S.-China conflict to spill over into geographies that Beijing deems as lying beyond the anti-access, area-denial range essential for its prosecution of a first island chain-specific contingency. The Indian Ocean and the south Pacific will remain as sideshows for the most part.

Finally, Beijing is no stranger to the notion of a bipolar order. Visions of a bifurcated world divided between two cultural spheres has civilizationally been central to its conceptualization of self and the other. That said, from a geostrategic perspective, Washington will find it arduous to assemble and deepen a bipolar coalition of allies and partners against China in the Indo-Pacific region. Militarily preponderant power in Moscow historically furnished the operation of the balance of power in Europe and invited periodic countervailing – including bipolar countervailing – alliances against its expansionist ambition. The establishment and consolidation of powerful centralized authority in China, on the other hand, has been the surest guarantor of peace, prosperity and stability in East Asia through millennia, with regional states bandwagoning with this outward radiation of Chinese influence. Besides, there is too much self-interested economic fraternizing with the supposed adversary for regional states to participate in a neat exclusionary allied coalition. Strategic competition against China in the Indo-Pacific region will have to be fought primarily with, and for, the loyalties of non-allied regional partners – a relatively unfamiliar terrain for American strategists.

George Kennan had counseled his countrymen in the penultimate paragraph of his celebrated essay to treat the issue of Soviet-American competition as “in essence a test of the overall worth of the United States as a nation among nations”. America needed only to measure up to its own best traditions to prevail and thereby prove itself worthy of preservation as a great nation. It remains wise counsel even today. America was once a beacon of liberty and prosperity, its economic and political system the envy of the world. American postwar statesmen built a global architecture premised on openness and universalism. Its economic might and its equally mighty dollar underwrote a system of free trade and open markets that engendered prosperity to all and was denied to none. Today, America’s political discourse has coarsened, its judicial opinion has regressed, its civic associations have fractured, and the drift towards economic nationalism is palpable. The dominance of the plumbing of the international economic architecture, and the public goods that it furnished, is being semi-privatized too within minilateral clubs and weaponized against adversaries and rejectionists. If cold wars are ultimately won with the soft power of attraction and persuasion, America must equally renew itself at home as it grapples with the China Challenge abroad.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2025 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Diverging Currents: U.S.–China Strategies on Deep Seabed Mining and the Future of Ocean Governance