Photo Credit: Prachatai (Flickr), Creative Commons

Resident Senior Fellow

The risk of a U.S.-initiated breakout of war, which could include a nuclear dimension as the conflict escalates, is as relatively low. Numerically, the risk is less than 30 percent – and probably much lower. Because North Korea (DPRK) is in a position to inflict unacceptable human losses on Seoul and U.S. assets in the region if the United States initiates a conflict, the consensus view in Washington is that the Trump administration will be deterred from initiating armed hostilities against North Korea.

The risk of a U.S.-initiated breakout of war on the Korean peninsula is nevertheless at its highest level since the armistice agreement that terminated the Korean War hostilities in 1953. Not since then has the evaluation by a U.S. administration of the threat status posed by North Korea been as high as it is today.

The risk of a U.S.-initiated breakout of war on the Korean peninsula has not yet peaked, and will continue to increase. The next 6 months will likely witness the highest-ever levels of tension on the Korean peninsula since 1953. The risk of a U.S.-initiated breakout of war, which could include a nuclear dimension as the conflict escalates, could even cross the 50 percent threshold during this time.

The key reason for this extremely elevated level of tension over the next 6 months is due to the Trump Administration’s primary policy focus vis-à-vis the DPRK: to deny North Korea the assured combat-ready capability to strike the continental United States with a nuclear-tipped missile. This does not necessarily mean that the administration will initiate a preventive or preemptive strike (or war) against North Korea. The United States will most likely learn to live with North Korea in a deterrence relationship once the latter perfects this capability. But for the time being, the overriding goal is primarily to deny North Korea the assured capability to hit America with a nuclear-tipped missile – by way of military means and economic strangulation (or diplomacy).

Despite the anticipated spike in tensions, there is guarded hope among specialists and observers that the two sides will avoid a military confrontation. Both sides will likely engage in aggressive posturing during this period, but, at the end of the day, each side will be dissuaded from pulling the trigger. Mutual deterrence will hold. The scope for a miscalculation, nevertheless, during this period however will be very high. The United States is set to conduct another round of joint military drills with South Korea in late-spring 2018, which Pyongyang typically views as a prelude to invasion.

The United States’ recent signaling of a qualified willingness to explore “talks about talks” with North Korea without the precondition of a prior commitment by Pyongyang to denuclearize, could lower the relative temperature on the peninsula during this period ahead. So long as: (a) a request is made by Kim Jong-un or a senior representative directly to the United States in this regard; and (b) North Korea commits to a sustained cessation of nuclear and missile testing as well as threatening behavior ahead of the talks, and during these talks, the U.S. appears willing to explore the potential for dialogue. Whether these dialogue threads will amount to much during this period of aggressive posturing remains to be seen. At best, it could provide a foundation for future bilateral and multilateral engagement once the period of high tension has elapsed.

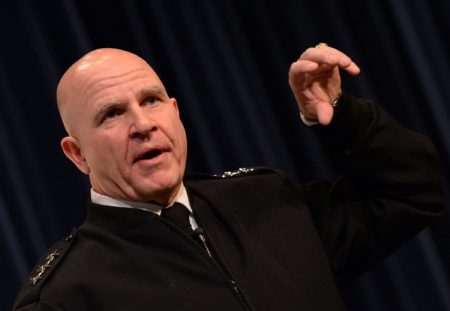

President Trump’s National Security Advisor, H.R. McMaster, has mentioned on at least three separate occasions, starting late-Summer 2017, that Kim Jong-Un will not be allowed to complete the development of a workable, nuclear-tipped, intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) capable of striking the continental United States. According to McMaster, if Mr. Kim achieves this goal, conventional deterrence will no longer be enough to deter him. Indeed, in McMaster’s view, the key intention of Kim Jong-Un in developing a nuclear ICBM strike capability is to blackmail the United States into abandoning its ally, South Korea, and thus clear the path for an invasion of the South, down the line, to unify the peninsula on North Korean terms.

As per this view, the policy of deterrence that worked effectively during the Cold War does not apply in the case of North Korea. Kim Jong-Un believes that if he can threaten the U.S. homeland with an assured nuclear strike capability, the U.S. will not risk intervention in a future North-South conflict on the peninsula. And because the U.S. will not risk intervention in the conflict, there will be no restraints on Kim’s aggressive behavior, whose ultimate aim is to militarily unify the peninsula under Pyongyang’s rule. Hence, to dissuade Kim Jong-Un from such aggressive conduct in the future leading potentially to a Second Korean War, North Korea must be denied the capability today to develop to a workable, nuclear-tipped, ICBM that can strike the continental United States and ‘decouple’ America’s security from that of its ally, South Korea. According to McMaster, the assumption that the North Korean regime wants nuclear weapons only to assure its survival is false and the Trump administration will not allow North Korea to develop the capability to hold the United States hostage with nuclear weapons during an eventual military contingency on the Korean peninsula. McMaster clearly iterated this point during the first weekend of December when he noted that “if necessary, the president and the United States will have to take care of it, because he has said he’s not going to allow this murderous, rogue regime to threaten the United States … it’s a regime who’s … intentions are to use that weapon for nuclear blackmail and then to … reunify the peninsula under the red banner.”

This view has also been endorsed by Mike Pompeo, the Director of the CIA. In mid-October, he observed that while Secretary of State Rex Tillerson was hard at work on the diplomatic front, “the president has made very clear he is prepared to make sure that Kim Jong-Un doesn’t have the capacity to hold America at risk – by military force if necessary.” An operational, nuclear-tipped ICBM in the hands of Kim Jong-Un is a game-changing existential threat to the United States, which Donald Trump is determined not to allow North Korea to possess. For his part, Secretary Tillerson has alluded to the commercial motivations that would compel North Korea to proliferate its technology as the reason why a nuclear-armed North Korea must not be allowed the comfort of settling into a steady, mutual deterrence relationship with the United States. White House Chief of Staff General John Kelly’s precise views on the issue are unclear, but he is generally thought to favor McMaster’s interpretation of the crisis.

The U.S. intelligence committee’s recent (August 2017) assessment of North Korea’s nuclear weapons program estimates that Pyongyang is less than a year away from having the assured capability of fitting a nuclear warhead on an ICBM and delivering it to any point in the continental United States. This has added a significant element of urgency to the administration’s interpretation of the crisis. North Korea is thought to possess anywhere between 15 to 60 nuclear warheads, as well as an ICBM with the range – albeit lacking precision – that is capable of hitting the continental United States. It is unlikely that the two programs have been brought together to deliver a workable, nuclear tipped ICBM. The November 29th Hwasong-15, ICBM test-launch indicates that technological improvements are needed in the areas of heat-shielding and missile reentry, terminal guidance and warhead activation. However, these steps could likely be completed after two or three additional test firings, a process that could take roughly four to six months. CIA Director Pompeo affirmed this time-line in late-October when he noted that the DPRK is just “months away” from developing the assured capability to strike the continental United States with a nuclear-armed ballistic missile.

According to this line of argument, the Trump administration, has six months or less to deny Kim Jong-Un the assured ability to strike the United States – be it by military, economic or diplomatic means. As important elements within the Trump administration appear to see it, once North Korea obtains the assured capacity to strike the United States with a nuclear-tipped missile, the window for war will shut close very quickly. For a U.S. initiated military option to exist, it must take shape before North Korea completes its nuclear arsenal. The next 6 months provide the final opportunity to deny North Korea the ability to go nuclear with an assured ICBM strike capability – and, more broadly, the last opportunity to prevent the United States from being susceptible to future blackmail by Kim Jong-Un to abandon South Korea if he decides to attempt to reunify the peninsula by force.

U.S. military strike options vis-a-vis North Korea are a closely guarded secret. Presumably they span the range from decapitation strikes against the regime’s command and control infrastructure using special forces to all-out war. U.S. Defense Secretary Jim Mattis has presented preemptive strike and regime change options to the President, despite his personal reluctance to support such preemptive action. Allegedly, a notable feature of his presented options is that they entail no U.S. troop presence north of the 38th parallel after the liquidation of the Kim regime and the securing of its WMD assets. Beyond government, there are a range of hawkish views about what the Trump administration should do – (not to be confused with what the Administration will do). Below are two such representative views:

Representative View A: “The most dangerous provocation that North Korea has threatened is an (atmospheric) nuclear missile test firing over the Pacific Ocean. If North Korea does if fact launch a nuclear missile over and into the Pacific, the reaction should be a massive American and South Korean air and missile strike against all known DPRK nuclear test facilities and missile launching and support facilities. The strike should be launched from South Korean and Japanese bases, as well as U.S. ships and bases in the United States. Now is the time to consult with Japan and South Korea about this possibility as well as responses to other potential DPRK provocations. To launch a retaliatory strike of such scope, all three countries will need to increase their military readiness in case of North Korean retaliation and take steps to provide civil defense in South Korea and Japan to protect their citizens and the tens of thousands of Americans who live in both countries.” (retired Admiral Dennis Blair)

Representative View B: “Here is how Trump should respond (if Kim Jong-Un launches a long-range test missile towards the U.S.) – Take out the test site from which the North Koreans launched the missile, just like he (Trump) struck the military base in Syria from which the Assad regime had launched a chemical weapons attack on innocent civilians. Then, Trump should declare North Korea a ballistic missile “no-fly zone” and a nuclear weapons “no-test zone.” He should warn the North Koreans that any further attempts to launch a ballistic missile will be met with a targeted military strike either taking out the missile on the launch pad or blowing it up in the air using missile defense technology. And any further attempt to test a nuclear weapon will be met with a targeted strike taking out the test site and other related nuclear facilities. So long as North Korea does not retaliate, Trump should assure Pyongyang that he will take no further military action against the regime. However, if North Korea does retaliate, then the United States reserves the right to, as Trump put it to the UN General Assembly, “totally destroy North Korea.” (Marc Thiessen)

Regarding these representative views, there are three opposing points that bear noting. First, any military strike on North Korean territory is understood to be extremely risky. No one knows for sure how Kim Jong-Un will respond if his country is attacked – even if it is by way of a limited strike. There is no known knowledge of what his threshold for swallowing a (limited) strike is, i.e. the threshold beneath which Kim Jon-Un will not respond with a destructive counter-strike. The operating theory is that any attack on North Korean strategic or military assets on its territory will invite a devastating response from Kim Jong-Un.

Second, there is broad consensus that Kim Jong-Un is not suicidal. Rather, he calculates where the threshold of risk for inviting armed reprisals lies, and makes a point to operate beneath this threshold. Despite recent threats to target Guam with missile tests, North Korea has not launched a missile on a southward trajectory for many years. Despite threatening to conduct an atmospheric nuclear test over the Pacific Ocean, Kim Jong-Un has conducted all his tests underground. Despite vowing to target the continental United States with an ICBM, all his three ICBM tests have been on a lofted trajectory and only one of these test missiles overflew Japan. These are strong indicators that Kim Jong-Un is a rational actor. He is not looking to invite an armed confrontation but is preparing himself fully if one does break out.

Third, no matter how devastating a U.S. strike on North Korea’s nuclear facilities and related targets might be, it will likely only be able to remove a small fraction them. Most of those strategic assets are stored underground in undisclosed locations, meaning that U.S. intelligence estimates about their precise location is imperfect at best. In late-October, the vice-director of the Joint Staff of the U.S. Navy, Michael Dumont, confirmed in written testimony to Congress that “the only way to locate and destroy with complete certainty all components of North Korea’s nuclear weapons program is through a ground invasion.” Without complete certainty that North Korea’s nuclear weapons program can be eliminated in a preventative strike, this option is disastrous. Kim Jong-Un would almost certainly order a retaliatory strike leading to a large loss of human life on the peninsula and beyond.

The broadest consensus on North Korea policy in Washington is that the United States should double-down on the approach of ‘maximum pressure’ and force the North Korean regime into submission through unrelenting economic sanctions. In this regard, the next step should be a complete oil embargo on North Korea. There are more thoughtful views in circulation that aim to tamp down on the tensions and provide an off-ramp to re-opening a dialogue process with Pyongyang. A representative view of this line of thinking is as follows:

The first step is to avoid a military conflict in the short run by making clear that a preventive military strike by the United States is not only unconstitutional and a violation of international law, but also inevitably catastrophic. Reducing the risk of preventive war by the Trump administration will also reduce the risk of a pre-emptive first strike by the DPRK if it fears that the United States is about to attack. At the same time, the Trump administration must take steps to ensure that South Korea and Japan have confidence in the American deterrent, and are not tempted to move towards their own nuclear capabilities. This is a serious long-term danger, but not an urgent threat since the current South Korean government is unlikely to move in this direction, and Japan cannot go first.

Step two is to negotiate a freeze on missile and nuclear tests by the DPRK. This will require the USG (United States Government) to move off the position that a freeze-for-freeze cannot be considered without preconditions. The opportunity presented by the Moon Jae-In government’s request to suspend military exercises in the spring at the time of the Olympics should be seized. A sufficient reduction in exercises going forward should be agreed so as to get agreement on a freeze in tests and the start of ‘talks about talks’.

Step Three. During the ‘talks about talks’, the purpose must be to seek agreement that the immediate goal of formal talks is to negotiate a permanent cessation not only of tests but of production of nuclear weapons material and long-range missiles in return for some easing of sanctions. There should also be agreement that the ultimate goal of the negotiations over a period of years is the de-nuclearization of the Korean Peninsula as part of a comprehensive and legally binding international agreement which also creates a security structure for northeast Asia and an end to hostilities and hostile intent among the six powers and ends sanctions.

Step four is to negotiate the terms of the verifiable freeze on production of nuclear weapons material and long-range missiles while providing sanctions relief to the DPRK. (Morton Halperin)

In mid-December, U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson signaled a qualified willingness to explore ‘talks about talks’ with North Korea without preconditions so long as: (a) a request is made by Kim Jong-un or a senior representative directly to the United States in this regard; and (b) the DPRK commits to a sustained period of cessation of nuclear and missile testing and threatening behavior ahead of the talks, and during the course of talks.

The Trump Administration’s overarching policy goal remains CVID (comprehensive, verifiable, irreversible denuclearization). That being said, as per the Tillerson view, the U.S. recognizes that North Korea has a lot invested in its nuclear and strategic program for now to accept the U.S. precondition that it commits to CVID before talks can be started. An important related concern in the U.S.’ eyes is also proliferation-risk – the potential for North Korea to sell its technology to bad state and non-state actors in the absence of any diplomatic engagement.

Tillerson’s overture comes at a delicate moment in the complex game dynamics of the Korean peninsula issue. Kim Jong-un still remains some tests away from a threshold point of assurance in terms of his delivery vehicles’ technical ability to strike the U.S. mainland with a nuclear warhead. It is possible that he will scheme for opportunistic breakdowns in the diplomatic process to upgrade and perfect his capabilities. For its part, the U.S. has yet to unleash its full toolkit of sanctions (most notably a U.N.-mandated oil embargo) and disincentives on the regime in Pyongyang. Until such sanctions are maxed-out and visibly seen to be impotent, the Trump Administration will not reconcile itself to any far-reaching bargain with a regime as odious as the North Korean one. Essentially then, Tillerson’s qualified willingness to explore a diplomatic pathway out comes at a time when both sides have yet to exhaust their options and reach a mutually unsatisfying but stable equilibrium atop which a durable settlement can be explored – let alone constructed. Whether the diplomatic process, including any round of ‘talks about talks’, can survive a further round of breakdown is a critically important question that will have a bearing on war and peace on the Korean Peninsula.

The current phase of tensions and the (severe) hardening of the Trump administration’s stance against North Korea can be traced to early-July of 2017. On July 4, North Korea conducted its first ICBM test, with the missile flying more than 4,000 miles and placing Hawaii and Alaska within its range. Later that month, on July 28, a second 6,000-mile ICBM test was conducted, bringing the West Coast of the United States and the Midwest within its range. These successful tests fundamentally altered the Trump administration’s perceptions of the existential threat posed by North Korea. President Trump’s hardline tone and inflammatory tweets about Kim Jong-un and National Security Advisor McMaster’s harsh analysis of North Korea’s strategy to blackmail and decouple the U.S.’ security from that of South Korea essentially date back to these two launches. Despite conciliatory noises by Rex Tillerson, Donald Trump has consistently maintained a hardline stance on the North Korea issue since the end of July. He, by and large, stopped communicating messages of reassurance after July 2017.

In September 2017, tensions escalated further. First, when North Korea conducted its sixth nuclear test on September 9th and later on when, on the floor of the U.N. General Assembly, Donald Trump proclaimed that North Korea might have to be “totally destroyed.” Kim Jong-Un interpreted that address as a “ferocious declaration of war” and promised that he would take “a corresponding, highest level of hardline countermeasures.” The next day, Kim’s foreign minister stated that North Korea “had entered a phase of completing the state nuclear force … [and that it] was only a few steps away from the final gate of completion of the state nuclear force.” Following the November 29th test-missile launch, which demonstrated North Korea’s capability to strike Washington, the regime announced that “the great historic cause of completing the state nuclear force” has been “realized.” Technical experts nevertheless believe that North Korea will need to conduct a few more tests before its nuclear deterrent is operational and combat-ready. These tests might take place over the next few months … although the regime’s assertion that its nuclear forces are completed suggests that Kim Jong-Un may be willing to call a pause/timeout on his testing program for a given (and undefined) period of time.

A key issue is whether or not the United States can deter a nuclear-armed North Korea if it develops the ability to target the U.S. homeland, and whether taking military action to prevent this scenario might be necessary. Either choice brings with it considerable risk for the United States, its allies, regional stability, and global order.

There is sub-set of hardened analysts’ views (some with prior U.S. government experience) who contend that the risk of allowing North Korea to develop the capability to target the U.S. homeland with a nuclear weapon outweighs the risks associated with a regional war. These analysts frequently cite Pyongyang’s history of bombastic threats, hostility toward the United States and its allies, and the regime’s long-stated interest in unifying the peninsula on its terms as evidence to back up their claim. The much larger mainstream faction of analysts and former government officials, however, see Kim Jong-Un as deterrable. War can, by-and-large, be avoided by implementing the policy of containment that kept the Cold War from going hot. North Korea needs to be convinced that any use of nuclear weapons or invasion of South Korea would invite a devastating response. For a long period of time ahead too – if ever, Kim Jong-Un will not enjoy the requisite conventional forces superiority to translate his ambitions of unification into reality.

At the end of the day, it all comes down to whether or not Trump and his administration believes that Kim Jong-Un is deterrable. And if not, whether over the next few months he must be denied the combat-ready capability to strike the continental United States with a nuclear-tipped missile. One way or the other, the conduct of both parties over the next six months will go a long way towards answering this question.

With assistance from Will Saetren

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2025 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.