Finally, India will be a stabilising power, prepared to use its security capabilities to help resist revisionism to the status quo and thereby maintain a more stable equilibrium – a key national interest in the Indo-Pacific region.

That said, the “Indo” and the “Pacific” are not created equal in the ordering of New Delhi’s security interests. East of the Indonesian island of Sumatra, these interests remain decidedly secondary. A wide-angled view of India’s diplomatic approaches and operational activities in that important waterway – the South China Sea – which links the Indian Ocean to the Pacific Ocean affords useful insights in this regard.

In January 2015, Modi and then US president Barack Obama issued a landmark Joint Strategic Vision for the Asia-Pacific and the Indian Ocean Region, which explicitly referenced the South China Sea and called upon all parties to ensure freedom of navigation and resolve disputes according to universally recognised principles of international law, notably UNCLOS.

By July 2016, following the South China Sea arbitration award in favour of the Philippines, India had conspicuously separated itself from the common US-Japan-Australia position calling on China to mandatorily abide by the decision. When Abe, an established China antagonist, visited New Delhi for the annual bilateral summit that year, India bent him to its will in the semantic formulation on the arbitration award that prevailed in their joint statement.

No navigational patrols have been conducted either by the Indian Navy in the South China Sea, in a joint or independent capacity. As a matter of policy, the navy conducts coordinated patrols at best – and that too only with maritime neighbours, Indonesia, Thailand and Myanmar.

As for its independent defence cooperation activities with the claimant states in the South China Sea, it is instructive to note what New Delhi has not provided or conducted. It has not sold offensive weapon systems to a South China Sea littoral state (despite long-standing ties with Vietnam). It has not deployed its vessels to this contested waterway to defend its economic interests. It has not laid out an operational doctrine to defend sealines of communication east of Malacca. And until earlier last month (when it conducted a maiden exercise with Vietnam), it had not engaged in a naval exercise – high-intensity or otherwise – with a South China Sea claimant state.

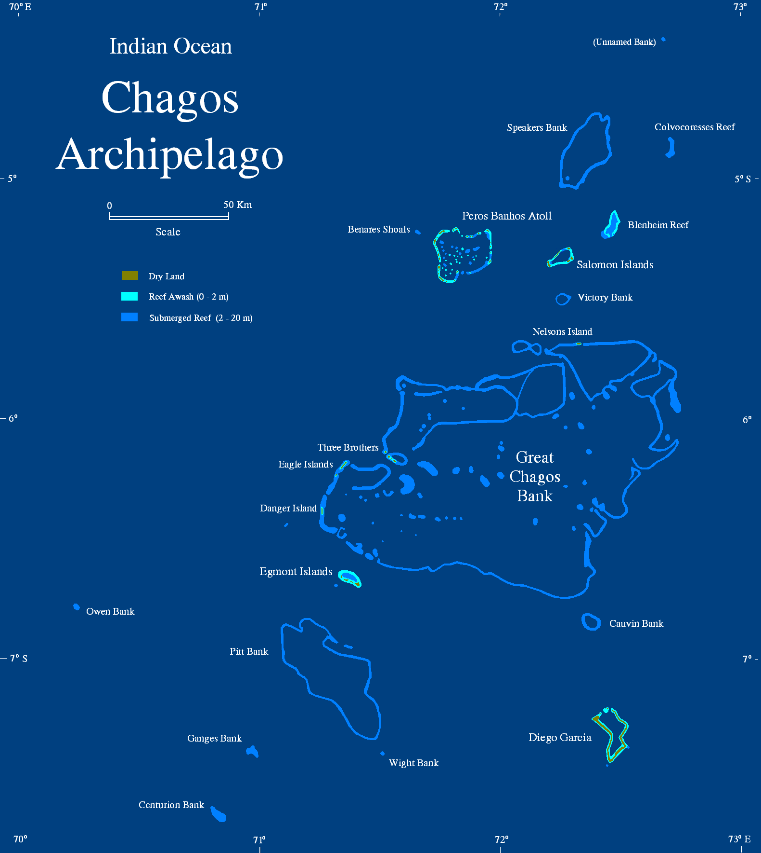

By contrast, in its core Indian Ocean area of interest, the Indian Navy and its political masters have been on a veritable tear, signing a spate of mutual logistics supply and reciprocal berthing agreements. From Djibouti and Reunion to Seychelles and Mauritius to Duqm (Oman) and Diego Garcia to Singapore and Denpasar (Indonesia), the Modi government has been busy stitching up its own “string of pearls” in this crucial thoroughfare.

At the end of the day, many of the same questions that abounded 20 years earlier about India’s strategic orientation and future role in the Indo-Pacific region will continue to ring into the future.

Will India seek to diplomatically forge a broad range of strategic partnerships in the Indo-Pacific while maximising its leverage by not aligning with any particular state or group of states? Or will it develop a preferred partnership with a select power or set of powers? Will India serve as an ‘external’ balancer in the region? Or will it, with a Machiavellian realism, contrive to lend its decisive weight to the winning side on the immediate regional challenge of the day?

Will India seek to forge a ‘natural alliance’ of democratic states along the Indo-Pacific periphery, framed in conscious distinction to China and its regional interests? Or will it seek to articulate an alternate Asian model of international relations that is keyed to regional tradition and historical circumstance?

India’s leaders from Jaswant Singh to Narendra Modi have displayed a consistent grasp of the country’s strategic purposes in the Indo-Pacific region, despite the breadth and depth of these questions. Observing and carefully tracking India’s actions, both, at the table of diplomacy and on the ground and at sea, will provide the most enduring clues to New Delhi’s own vision of its role in this Asian and Indo-Pacific Century.

This article originally appeared in the South China Morning Post.

A Test for the Future of Global Ocean Law