U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken walks around Shanghai, China at night on April 26, 2024.

(Source: Official State Department photo by Chuck Kennedy, Public Domain)

Resident Senior Fellow

This article is extracted from Comparative Connections: A Triannual E-Journal of Bilateral Relations in the Indo-Pacific, Vol. 26, No. 1, May 2024. Preferred citation: Sourabh Gupta, “US-China Relations: Ties Stabilize While Negative Undercurrents Deepen,” Comparative Connections, Vol. 26, No. 1, pp 39-54.

US-China relations were marked by a paradox during the first trimester of 2024. On the one hand, a distinct stabilization was evident in ties. The two sides made concerted efforts to translate their leaders’ ‘San Francisco Vision’ into reality. Cabinet officials exchanged visits across the Pacific, working groups and dialogue mechanisms met in earnest and produced outcomes, functional cooperation was deepened, sensitive issues such as Taiwan were carefully managed, and effort was devoted to improving the relationship’s political optics. On the other hand, the negative tendencies in ties continued to deepen. Both sides introduced additional selective decoupling as well as cybersecurity measures in key information and communications technology and services sectors, with US actions bearing the signs of desinicization—rather than mere decoupling—of relevant supply chains. The chasm in strategic perception remained as wide as before. In sum, the “new normal” in US-China relations continued to take form, one piece at a time.

What a difference a year makes. At this time in late-April last year, the US and China were barely communicating, still smarting from the balloon incident of February 2023. It was not until US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan and CPC Central Foreign Affairs Commission Director Wang Yi met in Vienna in mid-May 2023 that a semblance of normality began to be restored to the relationship. Twelve months on, there has been an almost across-the-board restoration of communication channels, a deepening of functional cooperation across issues areas, and a concerted effort to manage the political optics of the relationship for the better – this, despite deep differences in strategic perception between the two sides.

The first four months of 2024 witnessed a flurry of in-person meetings of Cabinet and principals-level officials. On Jan. 18, US Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack met counterpart Tang Renjian in Washington, DC, marking the first meeting of their Joint Committee on Cooperation in Agriculture since 2015. Eight days later, US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan and Director Wang Yi held 12 hours of talks over two days in Bangkok, their third extended round of conversations following meetings in Vienna (March 2023) and Malta (September 2023). At the meeting, a decision to launch a bilateral working group on counternarcotics and an inter-governmental dialogue mechanism on artificial intelligence (AI) later this spring was reached. On Feb.18, China’s Minister of Public Security Wang Xiaohong met US Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas in Vienna to advance law enforcement cooperation in the fights against fentanyl as well as online child sexual exploitation. The harassment of Chinese students at US border entry points was also raised by Wang.

In early April, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen returned to Beijing to establish two dedicated workstreams in conjunction with her Chinese Finance Ministry and People’s Bank of China (PBoC) counterparts—an Intensive Exchange on Balanced Growth in the Domestic and Global Economies under the aegis of their bilateral Economic Working Group (EWG), and a Joint Treasury-PBoC Cooperation and Exchange on Anti-Money Laundering (AML) under their Financial Working Group (FWG). The former workstream is informed by concerns of excess Chinese capacity in key new industries such as solar, electric vehicles (EV) and lithium-ion batteries, and bears resemblance to the Strategic Impediments Initiative (SII) that the US and Japan devised three-and-a-half decades ago to tackle the structural drivers—many of them in the domestic regulatory policy realm—that Washington believed was behind the large trade imbalance between the two sides. Beijing denies the overcapacity charge in the EV sector, pointing out that 12% of Chinese-made EV’s are exported compared to 80, 50, and 25% of autos for Germany, Japan and the US, respectively.

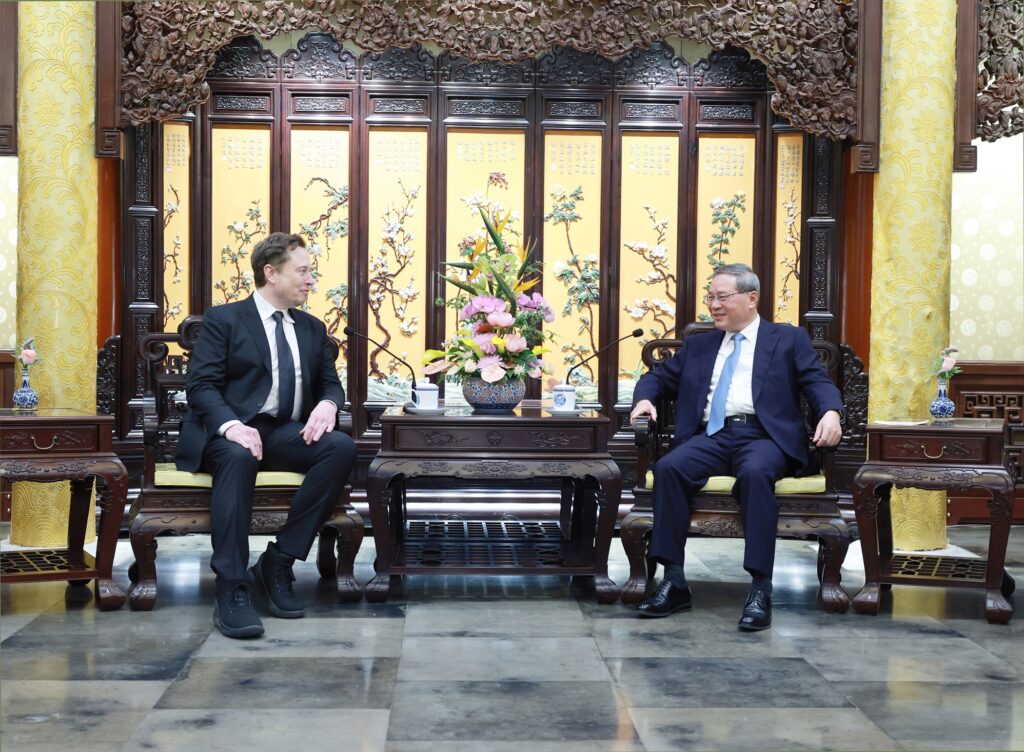

On April 24-26, 10 months after he had set the ball rolling with his ice-breaking visit, Secretary of State Antony Blinken returned to Beijing to hold “candid and constructive” conversations with President Xi, Foreign Minister Wang and Minister of Public Security Wang Xiaohong. The composition of senior departmental officials accompanying Blinken was instructive of his priorities: counternarcotics cooperation and AI. It included Todd Robinson, assistant secretary for Intl. Narcotics and Law Enforcement, and Nathaniel Fick, ambassador for Cyberspace and Digital Policy (in addition to Dan Kritenbrink, the asst. secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs). On global affairs, China’s transfer of dual-use items to plug critical gaps in Russia’s defense production cycle and thereby support Moscow’s operations in Ukraine was the foremost topic of discussion. In Beijing, Blinken threatened his Chinese interlocutors with secondary sanctions on its banking sector, should they facilitate ‘significant transactions’ on behalf of entities that provide specific manufacturing inputs and technologies to Russia’s military-industrial base. That Beijing is attentive to this threat can be gauged from the fact that following the issuance of Biden’s December 2023 Executive Order authorizing the imposition of US secondary sanctions on foreign financial institutions, three of China’s largest banks – Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC); China Construction Bank (CCB); Bank of China—stopped accepting payments from sanctioned Russian financial institutions. After Blinken’s departure, a number of Chinese and Hong Kong entities that supply drones, infrared detectors, microelectronics, sensors and microcontrollers, and nitrocellulose (to make propellants) for Russia’s war machine were slapped with property-blocking sanctions by the Treasury Department. No Chinese banks were included in the current round of sanctions.

On Taiwan, both Blinken and his counterpart spelt out their respective “one China” policy and “one China” principle, and counseled restraint. With a presidential election in January on the self-governing island and with the inauguration of a deeper-green president looming in May, both sides conveyed their bottom lines while maintaining fidelity to the cross-strait status quo. Though Beijing had snapped back at Washington’s congratulatory statement in January following the DPP candidate Lai Ching-te’s victory and snapped again following US support for Taiwan’s participation as an observer at the World Health Assembly later in May, the CCP’s Taiwan Affairs Work Conference in end-February and the PRC Government Work Report of early-March stuck to the standard theme of “peaceful development of cross-strait relations” and “advancing integrated cross-strait development.” Sanctions were imposed though on five US defense industry companies for arms sales to Taiwan.

In addition to these in-person meetings, two notable meetings were conducted virtually. On April 2, President Biden and President Xi took stock of the progress as well as continuing deep differences in ties since their November 2023 summit in California. Biden reemphasized that the US does not seek a new Cold War; does not seek to change China’s system; the revitalization of its alliances is not directed at China; does not support Taiwan independence; and does not seek conflict with China. For his part, Xi has sought to follow through on his people-to-people pledges, and leaven the political tone of the US-China relationship at a time when a whopping 80%-plus of Americans hold an unfavorable view of the People’s Republic. In February, the China Wildlife Conservation Association and the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Association signed an agreement to return two giant pandas to the San Diego Zoo later this summer—the first time in more than two decades that pandas will be returning to the US. A letter of intent with the San Francisco Zoological Society was also signed on April 19. On March 27, Xi met with representatives of the US business community at the Great Hall of the People—his first meeting with a visiting US business delegation since September 2015. And in his continuation of “letter diplomacy,” Xi exchanged missives with friends and students from Muscatine, Iowa, where he had visited, stayed, and cherished fond memories from 39 years ago. Allowable weekly round-trip passenger flights between the two countries have also inched up to 50, from 12 per week in August 2023, to 18 in September, to 24 in end-October, to 35 in late-November 2023. Prior to COVID-19, the number had exceeded 150 per week.

The other notable video meeting was between the two defense chiefs. On April 16, US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin III held his first talks since November 2022 with a PRC Minister of National Defense (Adm. Dong Jun), with Taiwan and the South China Sea tensions being the key topics of discussion. A day later, a Navy P-8A Poseidon patrol and reconnaissance plane conducted a relatively rare Taiwan Strait transit in international airspace. Earlier, in January and in early-April, the 17th Defense Policy Coordination Talks (DPCT), an annual deputy assistant secretary level policy dialogue, and the Military Maritime Consultative Agreement (MMCA) talks, a working-level operational safety dialogue between US INDOPACOM and PLA naval and air forces, were held. Defense communication channels appear to be reverting to normal and instances of China’s risky aerial intercepts are down significantly. In fair likelihood, the two countries’ defense chiefs will hold their first in-person meeting on the sidelines of the Shangri-La Dialogue in end-May—the first in-person contact since the post-balloon incident easing cycle in ties began last summer. Separately, the US was among 29 navies gathered at the Western Pacific Naval Symposium (WPNS) in Qingdao, China, where an updated Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea (CUES) and the forming of a Working Group on Unmanned Systems were adopted.

In the run-up to the November 2023 summit in Woodside, the Chinese and US climate envoys had released a (rare) joint statement committing both countries to deeper cooperation on methane reductions. To consolidate the momentum in ties, the two presidents agreed at their meeting to establish a working group on counternarcotics cooperation and convene an intergovernmental dialogue mechanism to address the risks of advanced artificial intelligence systems. Varying progress was made on both fronts.

Counternarcotics Cooperation, including on fentanyl control

In Woodside, the Biden administration had agreed to delist the Chinese Ministry of Public Security’s Institute of Forensic Science from its Entity List, as part of an arrangement to establish a counternarcotics working group and effectuate concrete actions to stem the flow of fentanyl precursor chemicals into North America. In the run-up to that summit, China’s National Narcotics Control Commission had sent out notices to Chinese chemical companies warning of potential criminal liability for selling chemicals for the production of narcotics, including those listed in the US Drug Enforcement Administration’s list of chemicals of concern.

Following the summit, China began reporting incidents for the first time in three years to the International Narcotics Control Board database used by law enforcement authorities to track and intercept shipments. At their Counternarcotics Working Group meeting in late-January, the two sides agreed to clamp down on Chinese pill press exports (which enable the production of potentially lethal fentanyl-laced fake pills) and share best practices with regard to closing money laundering loopholes. The January meeting was attended by representatives from Chinese banks, including the Bank of China. The US has sought tougher prosecution and sentencing of those accused of selling precursor chemicals and related equipment, as well as expeditious follow-through by Beijing on the scheduling of all chemical precursors controlled by the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs. China has sought to have its listing as a ‘major drug source country’ removed. The Biden administration placed Beijing on its annual list of major drug-producing or transit countries in September 2023.

Artificial Intelligence dialogue

On March 21, the US and China along with more than 120 countries supported a landmark resolution on the promotion of “safe, secure and trustworthy” AI systems that would benefit the sustainable development of all. A month later, during Secretary Blinken’s visit to Beijing, the two countries formally announced the 1st US-China talks on AI, due to be held in the coming weeks. The purpose of the talks is to better understand respective views and approaches to managing the risks associated with AI applications, and to communicate about areas of concern. Both countries are in the process of developing guidelines, standards and best practices for AI safety and security, and are involved too in the advancement of global technical standards for AI development. Topics being addressed include best practices regarding data capture, processing, management, and analysis; best practices for AI model training; guidelines and standards for trustworthiness, verification, and assurance of AI systems; AI risk management and governance systems; as well as application-specific standards (e.g., for facial recognition technology), among others. That said, structuring the US-China conversation on AI will not be easy.

The primary focus of the bilateral conversation, from Washington’s point of view, is to develop common approaches on the development and control of high-risk frontier AI models. Beijing’s preference, on the other hand, is that the bilateral conversation be focused on the cooperative development of AI. The Biden administration has no interest in such a conversation; to the contrary, the administration has placed onerous export control restrictions on leading-edge GPU’s (graphics processing units) to prevent China from training its frontier AI models. At the Bletchley Park AI summit last November, at which China was among two dozen-odd countries represented, the US even ensured that Chinese companies were excluded from the testing of frontier models at the AI safety institutes set up by the US and UK. This begs the question how risks, standards, and regulations on frontier models can be individually or mutually evaluated and established. On the military side of things, meanwhile, one of the working group’s aim is to establish certain rules-of-the-road to ensure that unsupervised AI is not allowed to dictate command-and-control of critical weapon systems, particularly those related to the use of a nuclear weapon. Regulating the use of AI in fully autonomous weaponry is another potential focus area. That said, neither side as yet deploys frontier AI models to guide critical military operations-related applications—which, in turn, begs the question as to who would even represent either side on military AI at the discussion table. As the working group convenes, these and other questions remain to be answered.

Science & Technology Agreement (STA) Extension

The STA was the first major agreement signed by the two governments following the re-establishment of diplomatic relations in January 1979. This framework agreement, which covers around 30 agency-level protocols and 40 sub-agreements that cover the gamut from agriculture, basic science, biomedical research, marine sciences and remote sensing to nuclear fusion and safety, provides the mutual confidence that sustains and underpins cross-border research collaborations. Last renewed in 2018 and extended for six months in August 2023, the STA was quietly extended for another six-month interval in late-February 2024 while negotiations on its renewal continue. From the standpoint of modernizing the agreement, several sticking points remain. These include the personal safety of scientists who travel to China; their ability to access, share and carry data across China’s borders at this time of tight data security rules; concerns regarding IP theft; and concerns about a lack of reciprocity, transparency and a level playing field in terms of access for US scientists in China.

The Chinese side has its own interests and concerns too, not least among them being the poaching of its scientists by the US. A dispute settlement framework also needs to be worked out. That said, the Biden administration’s decision to successively extend the STA—albeit temporarily, when it could easily have played to the political gallery and let the agreement expire—signifies a willingness to engage China as a scientific near-peer than purely as a target of suppression.

In his phone conversation with Biden on April 2, Xi Jinping lamented that even as the US-China relationship was beginning to stabilize, the “negative factors of the relationship [were] also growing.” The two sides needed to first get the “issue of strategic perception” right, “just like the first button that must be put right.” That first button is not likely to be worn as per Xi’s liking. The Biden administration’s approach, as it has stated many times, is to invest (in itself), align (with allies and partners), and compete (with China), and only thereafter manage the competition from veering into conflict while also seeking out areas of cooperation.

During the first trimester of 2024, such competitive actions foremost in the advanced technologies and cybersecurity sphere remained the dominant trend. The whiff of protectionist-leaning trade policy announcements that cater to blue collar voters in toss-up electoral college states was evident too. Beijing was no shrinking violet either; it implemented countermeasures as well as self-introduced de-risking actions during this period.

Cybersecurity concerns involving China have long risen to the fore in US politics and national security. In February, FBI Director Christopher Wray delivered a blistering critique at the Munich Security Conference of China’s pre-positioning of malware within critical infrastructure systems. While Wray and the Justice Department have not always been on the money on China (witness the implosion of the “China Initiative” cases and the failure to make trade secrets theft charges stick against Fujian Jinhua Integrated Circuit Co.), his critique was a prelude to three Biden administration Executive Orders in the space of 10 days on China-linked cybersecurity concerns. On Feb. 21, an EO that addresses cyber-vulnerabilities linked to ship-to-shore cranes produced in China was rolled out, following reports as well as a congressional investigation that such cranes deployed at more than 200 US ports contained remotely accessible communications equipment (cellular modems) that was unneeded for normal operations. On Feb. 28, an EO accompanied by a 90-page Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPRM) that is designed to restrict “foreign adversaries” access to Americans’ bulk sensitive personal data was released.

The ANPRM constitutes the first instance of the regulation of the personal data of Americans for national security reasons, rather than for privacy or other reasons. Its drivers stem as far back as the Anthem healthcare data breach of 2015, probably by Chinese operators, with the concern being that the stolen personal data from various sources of US citizens can be aggregated – utilizing big-data analytics, AI and data-brokers—and employed thereafter as a tool of blackmail and coercion. And tucked-in also on Feb. 28 was an EO and accompanying ANPRM that seeks to strip out foreign adversary content from key electric vehicle software systems – vehicle operating system; telematics systems; automated driving systems; advanced driver assistance systems; battery management systems; satellite/cellular telecoms system—that could potentially be commandeered by an adversary state to inflict a distributed denial of service attack on US intelligent transport systems, communication hardware, or critical infrastructure.

China went in a different direction on cyber concerns during the first trimester of 2024. On April 28, Tesla’s EV Model 3 and Model Y cleared four Cyberspace Administration of China’s (CAC)-recommended data security assessments related to the collection, processing, and management of data, paving the way for the lifting of access restrictions at sensitive locations, such as government compounds and airports. Earlier, on March 22, CAC issued an order rolling back restrictive regulations on the export of personal information and other sensitive data from China to facilitate the cross-border flow of data for business purposes.

Countering the potential for dissemination of disinformation by foreign adversaries, even be it subliminally, has been a US priority since the 2016 presidential election. To this end, on April 24, President Biden signed a bill, as part of a larger foreign aid package, that bans the popular short video-sharing app TikTok in the US if its China-based parent ByteDance fails to divest the app within 12 months. The Justice Department is authorized to enforce the ban on national security grounds. TikTok has vowed to challenge the law citing First Amendment protections. Its chances of success are high. Courts across the country and up to the Supreme Court have ruled that mere invocation of a national security threat based on supposition is insufficient to justify the squelching of First Amendment rights. The threat must be real, and a proposed ban shown to be an unavoidable option to address this threat. TikTok must be shown to have aligned its algorithm with Beijing’s disinformation efforts at the latter’s behest or coercion and likely to do so again, if such a ban is to be sustained. Neither the Trump White House in 2020 (which had ordered ByteDance to divest from TikTok) nor the foreign aid package bill today can likely mount this evidentiary threshold.

Relatedly, in late-August 2020, China’s Commerce Ministry had updated its list of “forbidden and restricted technology exports” to include “personalized information recommendation services based on data analysis”—in effect, meaning that ByteDance would need government approval (which would not be forthcoming) to effectuate a divestiture. That injunction remains just as applicable today. On the other hand, what is good for the goose does not seemingly apply to the gander, insofar as Beijing is concerned. In mid-April, while the TikTok bill was under consideration, it was reported that CAC had ordered Apple to remove popular Western chat messaging apps WhatsApp and Threads (as well as messaging platforms Signal and Telegram) from its app store on “national security” grounds. Mobile app developers had been required to register their apps with the Chinese government by April 1; as such, more app removals could follow in the coming weeks.

Strategic trade controls in the area of information and communications technologies and services (ICTS) has been ground zero in the US-China contest for tech supremacy, starting with the expansive ICTS Executive Order of May 2019 which initiated the process of kneecapping Huawei. On January 29, the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) issued a Proposed Rule that would compel US cloud companies to implement ‘know-your-customer’ procedures and alert the government when foreign clients train their most powerful AI models using the compute power provided by these cloud companies. The rule has been met with pushback from stakeholders. On Jan. 31, the US Defense Department released its updated list of 1260H “Chinese Military Companies” that “operate directly or indirectly in the United States.” While the legal impact of the designation is limited, it carries larger reputational risks for companies and could open them up to more severe sanctions later. On March 29, BIS issued its Interim Final Rule that revises elements of its punishing October 2022 and October 2023 rules aimed at restricting China’s ability to obtain advanced computing chips, develop and maintain supercomputers, and manufacture advanced node semiconductors. And in late-April, the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) ordered the US units of China Telecom, China Unicom, China Mobile and Pacific Networks Corporation to discontinue their Internet “Points of Presence” (POPs) operations that offer colocation, broadband, IP transit and data center services on American soil.

Having absorbed blow-after-blow of US technology denial measures, China, too, continued to impose countermeasures during the first trimester of 2024. In March, new procurement guidelines were introduced to phase out foreign operating systems, microprocessors and database software from government PCs and servers. In late-December 2023, the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology had issued introduced new “safe and reliable” criteria for processors and operating systems and on the same day, the China Information Technology Security Evaluation Center, the state testing agency, had published its first list of “safe and reliable” processors and operating systems—all locally produced. The muscling out of US technology from the state sector dates back to a directive issued in September 2022. Separately, China’s trade controls on graphite products continue to bite. Noting China’s lock on the spherical graphite and synthetic graphite supply chains—critical minerals key to the production of batteries, the US Treasury Department recently relaxed its clean vehicle tax credit-related sourcing rules in their regard for an additional two years until 2027.

Finally, the start of 2024 witnessed the return of the threat of aggravated trade frictions in US-China relations. The first shot of this new great power rivalry had been fired, it bears remembering, in the trade policy arena, when the Trump administration introduced Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum and Section 301 tariffs on $370 billion of Chinese goods in Summer 2018. With an eye on the battleground Rust Belt states in the 2024 election (Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin’s combined 77,736 vote margin was key to Trump’s victory in 2016; had 257,025 ballots been cast in his favor in these states, Trump would have remained in office in 2020), Biden called for a tripling of tariffs on Chinese steel and aluminum and a Section 301 probe into China’s shipbuilding, maritime, and logistics practices. A port fee on Chinese-built ships that dock at US ports is sought to be assessed, which would be plowed into a Shipbuilding Revitalization Fund to revive the domestic industry.

Separately, US Trade Representative Katherine Tai announced that her review of Section 301 tariffs on China that began in September 2022 is nearing completion, timed to land in the middle of campaign season. And all along, US Cabinet secretaries continued to beat the drum on Chinese overcapacity in key green goods sectors: solar, EVs, lithium-ion batteries. The accusation is not without merit. Although China is moving away from its excess investment-led growth model, the underlying level of domestic savings remains excessively high. As such, the fear that these savings (and domestic under-consumption) will macroeconomically manifest itself in the form of domestic overproduction that is dumped overseas in export markets is real. And because a component of this overproduction is the product of industrial subsidies, this would amount to unfair trade-distorting competition in international markets.

Beijing continues to resist this characterization pointing to its competitiveness in these industries. And, it initiated pre-case consultations with the US at the WTO regarding the latter’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) clean vehicle tax credits, which it alleges is a noncomplaint trade subsidy measure. On April 26, China’s National People’s Congress also passed a revised Customs Law, as part of a codification of tax practices, that includes a new authorization for the State Council to impose retaliatory tariffs (Article 18). And in late-April, China’s Ministry of Commerce announced new anti-dumping tariffs of up to 43.5% on imports of US propionic acid, a chemical additive used in animal feed and pesticides. Although the amounts involved are small, the measure is a shot across the bow given that Beijing had been reticent to escalate the already-high trade tensions.

The “new normal” in US-China relations continues to take shape, one piece at a time. The ‘new normal’ is not a ‘new Cold War’ as some have posited—although there is a palpable Cold War-style, zero-sum equation settling into their competition to dominate the high-technology and advanced manufacturing industries of tomorrow. Nor is the “new normal” merely a more contentious version of the mix of engagement and competition that characterized their four decade-long post-normalization period of ties. Strategic competition between the US and China is real and, if mismanaged, could drift into rivalry and across-the-board conflict—both hot and cold. That said, there is no one typology of interaction that cuts across the “baskets” of US-China issues; the two countries’ interactions, rather, span the range from the icy to the lukewarm. The two countries’ labor ministers have never met (the US insists that genocide and forced labor continues to be carried out in Xinjiang) and US Trade Representative Katherine Tai has yet to show up in-person in Beijing and explain her administration’s stance on the Section 301 China tariffs—now judged by a WTO panel to be unlawfully imposed. Positioned toward the latter end of the spectrum is their cooperation on climate change as well as Washington’s and Beijing’s engagement on bilateral and multilateral macroeconomic and financial issues, helmed by their Economic and Financial Working Groups. A complex relationship demands complex choices, built as much on ideology and values as it is on realism and objectivity.

In an article in Foreign Affairs in August 2019, 18 months before they assumed their role as architects of the Biden administration’s Indo-Pacific policy, Jake Sullivan and Kurt Campbell wrote of the imperative to establish a “clear-eyed coexistence [with China] on terms favorable to US interests and values.” America could, and should, both challenge and coexist with China. In Spring 2024, the spelling out of the terms of that ‘clear-eyed coexistence’ remains a work in progress, while Beijing continues to pursue its interests reactively within this framework.

January – April 2024

This chronology was prepared by Jessica Martin, ICAS Research Associate.

Jan. 4, 2024: US Secretary of State Antony Blinken releases a statement designating the People’s Republic of China as one of 12 “Countries of Particular Concern for having engaged in or tolerated particularly severe violations of religious freedom.”

Jan. 7, 2024: PRC foreign ministry announces the imposition of countermeasures against five US defense industry companies for arms sales to “China’s Taiwan Region” in accordance with its Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law.

Jan. 8-9, 2024: US Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for China, Taiwan, and Mongolia Michael Chase and PRC Deputy Director of the Central Military Commission Office for International Military Cooperation Major General Song Yanchao meet at the Pentagon for the 17th US-PRC Defense Policy Coordination Talks to discuss US-PRC defense relations.

Jan. 8, 2024: US Justice Department, in partnership with other government partners, sentences a US Navy service member to 27 months in prison “for transmitting sensitive US military information to an intelligence officer from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in exchange for bribery payments.”

Jan. 10, 2024: US Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas, accompanied by several other senior officials from various departments, meets with PRC Minister of Public Security Wang Xiaohong virtually to discuss “the importance of cooperating on key law enforcement issues, including combatting the illicit flow of synthetic drugs such as fentanyl and their precursor chemicals.”

Jan. 10, 2024: US Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo holds a phone call with PRC Minister of Commerce Wang Wentao.

Jan. 13, 2024: Secretary Blinken releases a statement congratulating Dr. Lai Ching-te on “his victory in Taiwan’s presidential election,” reiterating the US commitment “to maintaining cross-Strait peace and stability” and to the US ‘One China’ policy. PRC Foreign Ministry spokesperson “deplore[s] and firmly opposes” Secretary Blinken’s statement.

Jan. 18, 2024: US Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack meets with PRC Minister of Agriculture and Rural Affairs Tang Renjian, the first meeting since 2015 of the Joint Committee on Cooperation in Agriculture.

Jan. 18-19, 2024: Senior officials from the US Department of the Treasury and the People’s Bank of China, hold the third meeting of the Financial Working Group, the first time the meeting is held in China.

Jan. 23, 2024: US Permanent Representative to the United Nations Human Rights Council Ambassador Michèle Taylor, speaking on behalf of the 45th Session of the Universal Periodic Review Working Group, releases a statement on the PRC, listing recommendations and condemnations to the Secretariat of the Human Rights Council for the record.

Jan. 26-27, 2024: US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan meets Chinese Communist Party Politburo Member and Foreign Minister Wang Yi in Bangkok, Thailand for more than 12 hours over two days as part of efforts to “maintain open lines of communication and responsibly manage competition in the relationship as directed by the leaders” at the Woodside Summit in November 2023.

Jan 29, 2024: US Commerce Department issues a proposed rule that would compel US cloud companies to alert the government when foreign clients train their most powerful AI models using the compute power provided by these cloud companies.

Jan. 30, 2024: US Deputy Assistant to the President and US Deputy Homeland Security Advisor Jen Daskal leads an interagency delegation to Beijing to launch the US-PRC Counternarcotics Working Group, with both sides emphasizing “the need to coordinate on law enforcement actions; address the misuse of precursor chemicals, pill presses, and related equipment to manufacture illicit drugs; target the illicit financing of transnational criminal organization networks; and engage in multilateral fora.”

Jan. 30, 2024: Office of the United States Trade Representative releases the findings of its 2023 Review of Notorious Markets for Counterfeiting and Piracy, which lists several China-based e-commerce and social commerce markets, a cloud storage service, and “seven physical markets in China known for the manufacture, distribution, and sale of counterfeit goods.”

Jan. 31, 2024: US Federal Bureau of Investigation Christopher Wray testifies before the US House Select Committee on the Strategic Competition Between the United States and the Chinese Communist Party regarding the “CCP Cyber Threats to the American Homeland and National Security.”

Jan. 31, 2024: Department of Defense updates its list of names of “‘Chinese military companies’ operating directly or indirectly in the United States” in accordance with the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021.

Feb. 1, 2024: Deputy Secretary of Commerce Don Graves, speaking at the NTIA Spectrum Policy Symposium, says “[t]he US is engaged in a high-stakes, must-win competition over critical and emerging technologies with adversarial nations across the globe…As we speak, China is launching a concerted effort to dominate 5G deployment and the eventual development of 6G.”

Feb. 5-6, 2024: Senior officials from the Department of the Treasury and China’s Ministry of Finance hold the third meeting of the Economic Working Group, the first time the meeting is held in China.

Feb. 7, 2024: Department of Justice arrests an individual in California seeking to illegally transfer to China software and technology developed by the US government for use to detect nuclear missile launches and track ballistic and hypersonic missiles.

Feb. 7, 2024: US National Security Agency and partners issue a Cybersecurity Advisory titled “PRC State-Sponsored Actors Compromise and Maintain Persistent Access to US Critical Infrastructure.”

Feb. 7-8, 2024: USS John Finn (DDG 113) and USS Gabrielle Giffords (LCS 10) conduct trilateral operations with allied maritime forces from Japan and Australia in the South China Sea to “promote transparency, rule of law, freedom of navigation and all principles that underscore security and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific.”

Feb. 7-8, 2024: US Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs Victoria Nuland and EU Secretary General Stefano Sannino hold sixth high-level meeting of the US-EU Dialogue on China and the fifth meeting of the US-EU High-Level Consultations on the Indo-Pacific in which they discussed several issues including “the trajectory of their respective bilateral relationships.”

Feb. 9, 2024: US Navy and Philippine Navy conduct the third iteration of the Maritime Cooperative Activity in the South China Sea, “reaffirming both nations’ commitment to bolstering regional security and stability” and “in support of a free and open Indo-Pacific.”

Feb. 9, 2024: National Security Council releases a statement marking the two-year anniversary of the Indo-Pacific Strategy, reaffirming the US commitment to the region “amidst strategic competition with the People’s Republic of China.”

Feb. 12, 2024: US Space Force Chief of Space Operations Gen. Chance Saltzman delivers remarks at a public panel on great power competition, during which he names China as a “pacing threat” and explains “[w]e have to be able to assess…whether or not we are ready to engage an adversary like the PRC.”

Feb. 14, 2024: US Under Secretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence Brian Nelson, testifying before the House of Representatives Committee on Financial Services, lists China as a threat to the US financial system and affirms “we will safeguard our priority interests, along with those of our allies and partners, and will protect human rights.”

Feb. 15, 2024: FBI Director Wray, in remarks at the Munich Security Conference, highlights “The China Threat” and calls the Chinese government “the chief among those [cyber threat] adversaries.”

Feb. 15, 2024: USS John Finn (DDG 113) conducts a bilateral exercise with allied maritime forces from Japan in the South China Sea.

Feb. 16, 2024: Multi-agency Disruptive Technology Strike Force, led by the Departments of Justice and Commerce, releases a fact sheet on its one-year anniversary summarizing its progress in its mission to “prevent nation-state actors [including China] from illicitly acquiring our most sensitive technology.”

Feb. 20, 2024: White House hosts a background call to preview the “Biden-Harris Administration Initiative to Bolster the Cybersecurity of US Ports,” during which US Deputy National Security Advisor for Cyber and Emerging Technologies Anne Neuberger calls the People’s Republic of China-manufactured ship-to-shore cranes an “acute…cyber vulnerability.”

Feb. 21, 2024: Biden-Harris Administration issues an Executive Order to bolster the cybersecurity of US maritime ports, which includes a “Maritime Security Directive on cyber risk management actions for ship-to-shore cranes manufactured by the People’s Republic of China located at US Commercial Strategic Seaports.”

Feb. 21, 2024: US Senior Official for the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Jung Pak holds a videoconference with PRC Special Representative on Korean Peninsula Affairs Liu Xiaoming to discuss the DPRK’s increasing destabilization and its deepening military cooperation with Russia, with both parties agreeing on the need for stability and dialogue.

Feb. 23, 2024: Office of the USTR releases its 2023 Report to Congress on China’s WTO Compliance and Trade Representative Katherine Tai remarks how “China remains the biggest challenge to the international trading system established by the World Trade Organization” in spite of China having acceded to the WTO in 2001.

Feb. 24, 2024: G7 Leaders release a joint statement focused on the Russia-Ukraine conflict in which they express “concern about transfers to Russia from businesses in the People’s Republic of China of dual-use materials and components for weapons and equipment for military production.”

Feb. 25, 2024: US Ambassador to China Nicholas Burns conducts an interview with 60 Minutes in Beijing during which he summarizes the current state of US-China relations: “We’re going to compete. We have to compete responsibly and keep the peace between our countries. But we also have to engage.”

Feb. 26, 2024: Trade Representative Tai participates in a “robust” bilateral meeting with PRC Minister of Commerce Wang Wentao during the first day of the World Trade Organization’s 13th Ministerial Conference, resulting in the two parties agreeing “to work on areas of shared cooperation” as well as those of competition.

Feb. 28, 2024: Biden-Harris administration issues an Executive Order on Preventing Access to Americans’ Bulk Sensitive Personal Data and United States Government-Related Data by Countries of Concern.

Feb. 29, 2024: White House releases a Fact Sheet on taking action to “Address Risks of Autos from China and Other Countries of Concern.”

March 5, 2024: USS John Finn (DDG 113) conducts a routine south-to-north Taiwan Strait transit “through a corridor in the Taiwan Strait that is beyond any coastal state’s territorial seas.”

March 5, 2024: Department of State releases a press statement saying the US “stands with our ally the Philippines following the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) provocative actions against lawful Philippine maritime operations in the South China Sea on March 5,” also calling “upon the PRC to abide by the ruling and desist from its dangerous and destabilizing conduct.”

March 6, 2024: US Attorney General Merrick Garland announces the arrest and indictment of a Chinese national residing in California charged with theft of trade secrets in connection with an alleged plan to steal artificial intelligence-related technology from Google “while covertly working for China-based companies seeking an edge in the AI technology race.”

March 7, 2024: In his 2024 State of the Union speech, President Biden briefly refers to China directly, openly disagreeing that “China’s on the rise and America is falling behind” and lauding the Biden-Harris administration’s efforts to stay economically and technologically competitive with China.

March 11, 2024: Secretary of Defense Austin says the President’s Fiscal Year 2025 Defense Budget is “paced to the challenge posed by an increasingly aggressive People’s Republic of China.”

March 11-12, 2024: US Ambassador to China Burns, hosted by US Consul General Gregory May, visits Hong Kong for the first time in his role as US ambassador to China.

March 12, 2024: PRC State Council releases its Government Work Report, which affirms its interest in the “peaceful development of cross-strait relations” and “integrated cross-strait development.”

March 12, 2024: Trade Representative Tai releases a statement on a petition filed by five US national unions “requesting an investigation into the acts, policies, and practices of the PRC in the maritime, logistics, and shipbuilding sector,” noting that “[w]e have seen the PRC create dependencies and vulnerabilities in multiple sectors.”

March 15, 2024: US Ambassador to China Burns, speaking at a virtual seminar on US-China relations, calls the US and China competition “quite profound” and notes the two “will very likely be systemic rivals well into the next decade,” to which China’s Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Lin Jian responds that “Ambassador Burns has recently made negative comments on China on multiple occasions.”

March 19, 2024: Secretary Blinken, speaking at a joint news conference with his counterpart in Manila, reaffirms the “ironclad commitment” to the US-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty and how it “extends to any armed attacks…anywhere in the South China Sea,” to which Beijing immediately responds that the US has “no right to interfere.”

March 19, 2024: Department of Justice arrests a Canadian national and Chinese resident in New York for conspiring with a Chinese national “to send to undercover law enforcement officers trade secrets that belonged to a leading US-based electric vehicle company.”

March 21, 2024: Department of State Principal Deputy Spokesperson Vedant Patel, at a press briefing, says the US “recognizes Arunachal Pradesh as Indian territory” and strongly opposes any unilateral attempts to advance territorial claims.

March 22, 2024: Secretary Blinken releases a statement on Hong Kong’s New National Security Law that objects to its “vaguely defined provisions” and condemns “efforts to intimidate, harass, and limit the free speech of US citizens and residents.”

March 25, 2024: Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control sanctions a Wuhan, China-based “Ministry of State Security (MSS) front company that has served as cover for multiple malicious cyber operations.”

March 25, 2024: Department of Justice unseals an indictment of seven nationals of the People’s Republic of China who committed computer instructions in support of China’s Ministry of State Security targeting perceived critics of China in addition to US businesses and politicians.

March 27, 2024: Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen, speaking at Suniva in Norcross, Georgia, describes the “excess capacity that we are seeing in China” as a “particular” concern for the US and notes her Chinese counterparts will be pressed to address this issue.

March 27, 2024: President Xi meets representatives of US business, strategic and academic communities at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing. It is his first meeting with a visiting US business delegation since 2015.

March 28, 2024: US Embassy & Consulates in China celebrates opening of a newly relocated consulate facility in Wuhan, China, which US Ambassador Burns and several Ministry of Foreign Affairs and other Chinese representatives attended and expressed support for.

March 28, 2024: Department of Defense releases its Defense Industrial Base Cybersecurity Strategy 2024, which lists China as “A Major Disruptor” and asserts China’s goal is to “[c]onstrain the US and become the Commercial Center of Gravity in the World.”

March 29, 2024: Secretary Blinken releases to US Congress the Hong Kong Policy Act Report for 2024, commenting that “[t]his year’s report catalogs the intensifying repression and ongoing crackdown by PRC and Hong Kong authorities on civil society, media, and dissenting voices” and subsequently announcing the Department of State “is taking steps to impose new visa restrictions on multiple Hong Kong officials.”

April 2, 2024: Department of Homeland Security releases the Cyber Safety Review Board’s findings and recommendations following its independent review of the Summer 2023 Microsoft Exchange Online intrusion, which found that the intrusion was conducted “by Storm-0558, a hacking group assessed to be affiliated with the People’s Republic of China.”

April 3-4, 2024: Representatives from US Indo-Pacific Command, US Pacific Fleet, and US Pacific Air Forces meet with People’s Liberation Army representatives in Honolulu, Hawaii for the first Military Maritime Consultative Agreement working group held since December 2021.

April 4-5, 2024: US-EU Trade and Technology Council holds its sixth ministerial meeting and releases a joint statement saying the parties have “engaged with other countries who share our concerns about China’s non-market policies and practices in the medical devices sector, and conveyed these concerns directly to China.”

April 6, 2024: Secretary of the Treasury Yellen meets with Chinese Premier Li Qiang in Beijing, China to deepen bilateral discussions.

April 7, 2024: Secretary of the Treasury Yellen meets Minister of Finance Lan Fo’an to discuss the role of their departments in “maintaining a durable communication channel between the US and China.”

April 8, 2024: Secretary of the Treasury Yellen, speaking at a press conference in Beijing, reviews the “significant progress” made in the US-China economic relationship over the last year and during her visit to China, concluding “[t]here is much more work to do” as the US aims to find “a way forward so that both countries can live in a world of peace and prosperity.”

April 9, 2024: Administrator of the US Agency for International Development Samantha Power, testifying before the Senate, details China’s “global lending spree” and “flagrant disregard for human rights” as a case of how “other global powers are working aggressively to erode US alliances, undermine democracy, and diminish basic rights and freedoms.”

April 11, 2024: Leaders of Japan, the Philippines and the US hold an inaugural trilateral summit and release a joint vision statement that highlights their “serious concerns” about aggressive, dangerous and coercive behavior in both the South China Sea and East China Sea.

April 12, 2024: Inaugural US-Philippines 3+3 Meeting is held in Washington, D.C., during which both parties deepened coordination on issues including “repeated harassment of lawful Philippine operations by the People’s Republic of China.”

April 14-16, 2024: US Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs Daniel Kritenbrink and US National Security Council Senior Director for China and Taiwan Affairs Sarah Beran meet Ministry of Foreign Affairs Executive Vice Foreign Minister Ma Zhaoxu, Director General of the North American and Oceanian Affairs Department Yang Tao, and Taiwan Affairs Office Deputy Director Qiu Kaiming in Beijing, “as part of ongoing efforts to maintain open channels of communication and responsibly manage competition.”

April 16, 2024: Trade Representative Tai testifies before the Senate Committee on Finance that the Biden administration “will continue to stand up to China’s unfair, non-market policies and practices” alongside partners and allies, emphasizing the complexity of the bilateral relationship and echoing President Joe Biden’s sentiments that “we want competition with China, not conflict.”

April 16, 2024: Fourth US-People’s Republic of China Economic and Financial Working Groups are held in Washington, DC, both of which discuss macro- and micro-issues of import and conclude with mutual commitments to continually deepen bilateral communications.

April 16, 2024: US Assistant Secretary of State for Educational and Cultural Affairs Lee Satterfield meets with the China’s Vice Minister of Culture and Tourism Li Qun in Washington, to discuss cooperation and collaboration specific to archaeology and cultural heritage.

April 17, 2024: A US Navy P-8A Poseidon surveillance aircraft transits the Taiwan Strait in “international airspace.”

April 17, 2024: President Biden gives a speech in a presidential campaign stop at the United Steelworkers Headquarters in Pennsylvania titled “New Actions to Protect US Steel and Shipbuilding Industry from China’s Unfair Practices.”

April 17, 2024: Office of the USTR, following a review of a petition filed on March 12 by five US national labor unions, initiates a Section 301 investigation into “the PRC’s longstanding efforts to dominate the maritime, logistics, and shipbuilding sectors.” Beijing expresses strong dissatisfaction to the investigation.

April 19, 2024: G7 foreign ministers release a “Statement on Addressing Global Challenges, Fostering Partnerships” in which they “recognize the importance of constructive and stable relations with China” and reaffirm interest in “a balanced and reciprocal collaboration with China aimed at promoting global economic growth,” among other issues and concerns.

April 19, 2024: US Ambassador to the China Burns meets Special Envoy Zhai Jun of the Chinese Government on the Middle East Issue in Beijing.

April 21, 2024: US and 28 other navies gather at the Western Pacific Naval Symposium (WPNS) in Qingdao, China, where an updated Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea (CUES) and the forming of a Working Group on Unmanned Systems is adopted.

April 22, 2024: US-Philippine 39th Balikatan Exercise, joined in part by the French navy and set to conclude on May 10, kicks off in the South China Sea region.

April 23, 2024: President Biden signs into law a bill that would ban TikTok in the United States unless it is divested by its Chinese owner ByteDance within a year.

April 24, 2024: Department of State releases a Joint Statement on the Philippines-United States Bilateral Strategic Dialogue which reaffirms US support for the 2016 South China Sea Arbitration ruling concluded by the Permanent Court of Arbitration.

April 25, 2024: Department of Justice unseals an indictment of two Chinese nationals for crimes related to a conspiracy to illegally export US semiconductor manufacturing technology to “prohibited end users in China.”

April 25, 2024: Federal Communications Commission orders the US units of four Chinese telecom companies to discontinue fixed or mobile broadband operations within 60 days, as part of a larger net neutrality order.

April 26, 2024: Secretary of State Blinken travels from Shanghai to Beijing and meets separately with President Xi Jinping, Director of the Chinese Communist Party Central Foreign Affairs Commission and Foreign Minister Wang Yi, Minister of Public Security Wang Xiaohong to follow up on commitments made at the Woodside Summit in November 2023, discuss “responsibly managing competition,” and address a range of other global concerns including Russia’s industrial base, the conflicts in Ukraine and the Gaza Strip, human rights, illicit drugs, and artificial intelligence.

April 26, 2024: Department of Homeland Security announces the establishment of the Artificial Intelligence Safety and Security Board to advise the Department and the broader public on the “safe and secure development and deployment of AI technology in our nation’s critical infrastructure” to stay ahead of potentially hostile nation-state actors such as the PRC.

April 26, 2024: Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress adopts a revised Customs Law that includes a new authorization for the State Council to impose retaliatory tariffs.

April 29, 2024: US and Taiwan start another in-person negotiating round for the US-Taiwan Initiative on 21st Century Trade in Taipei, Taiwan.April 30, 2024: Department of Labor Deputy Undersecretary for International Affairs Thea Lee, testifying before the Congressional-Executive Commission on China, argues that “ongoing human and labor rights violations in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region” make reliable audits “impossible.”

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2025 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Opinion | As China modernises its navy, the US races to stay ahead