WASHINGTON, DC – FEBRUARY 22: U.S. President Joe Biden arrives to deliver remarks from the East Room of the White House February 22, 2022 in Washington, DC. (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

Resident Senior Fellow

This article is extracted from Comparative Connections: A Triannual E-Journal of Bilateral Relations in the Indo-Pacific, Vol. 25, No. 1, May 2023. Preferred citation: Sourabh Gupta, “US-China Relations: US-China Effort to Set “Guardrails” Fizzles with Balloon Incident,” Comparative Connections, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp 33-46.

The proposed “guardrail” that Joe Biden and Xi Jinping sought to erect last fall in Bali failed to emerge in the bitter aftermath of a wayward Chinese surveillance balloon that overflew the United States and violated its sovereignty. Though Antony Blinken and Wang Yi met on the sidelines of the Munich Security Conference afterward, aspersions cast by each side against the other, including a series of disparaging Chinese government reports, fed the chill in ties. Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen’s meeting with House Speaker Kevin McCarthy during the return leg of her US transit added to bilateral and cross-strait tensions and were met with Chinese sanctions. Issues pertaining to Taiwan, be it arms sales or a speculated Chinese invasion date of the island, remained contentious. The administration’s attempt to restart constructive economic reengagement with China, including via an important speech by US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, appears to have fallen on deaf ears in Beijing.

Following the Biden-Xi meeting on Nov. 14 on the sidelines of the G20 Leaders Summit in Bali, Indonesia, US-People’s Republic of China relations were transitioning to an improving track—or so it seemed. US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin met with his Chinese counterpart, Defense Minister Wei Fenghe, on the sidelines of the ASEAN Defense Ministers” Meeting-Plus meeting in Cambodia on Nov. 22. On Dec. 11-12, US Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs Daniel Kritenbrink held “candid, in-depth and constructive” talks in Beijing. On Jan. 18, Secretary Yellen had a “candid, substantive, and constructive conversation” with departing Vice-Premier Liu He in Zurich ahead of the World Economic Forum in Davos. Hours before Secretary Blinken was due to board a flight to Beijing on Feb. 3, which would have been the highest-ranking contact between the two sides since the Bali meeting, the budding rapprochement came to a screeching halt.

Two days earlier, on Feb. 1, a high-altitude balloon was spotted in the sky over Billings, Montana; it was followed by a Department of Defense statement and a background briefing the next day identifying it as a high-altitude surveillance balloon of PRC provenance. A second balloon had also been spotted over Latin America. The Chinese foreign ministry was quick to admit responsibility on Feb. 4, confirming the “unintended entry of a Chinese unmanned airship into US airspace due to force majeure.” With “limited self-steering capability,” the airship had apparently “deviated far from its planned course”—a claim a US official speaking on background appeared to validate on Feb. 15. The planned track would have taken the balloon over Hawaii and Guam, home to key US military installations—speaking in turn to the balloon’s defense surveillance purpose. The Feb. 4 Chinese statement observed however that the airship was a “civilian” one “used for research, mainly meteorological, purposes,” and that China had “no intention of violat[ing]…the territory or airspace of any sovereign country.” The balloon’s flight over US airspace was, after all, a violation of the territorial sovereignty of the United States as well as of Article 3 of the Convention on International Civil Aviation (“no state aircraft of a contracting state shall fly over the territory of another state…without authorization”). Privately, an expression of regret was tendered to US counterparts—one that was acknowledged by a senior State Department official at the time of protesting the incursion and announcing the postponement of the Blinken visit.

Regret turned to anger in Beijing, however, when the balloon was downed by an F-22 fighter jet on Feb. 4 and significant portions of its payload retrieved from within US territorial waters off the coast of South Carolina (the balloon overflew the entire continental United States). This “use of force [was a] clear overreaction and serious violation of international practice”—although not necessarily of law, Beijing protested, pointing presumably to the US’s alleged excessive use of force against a civilian airship in distress (Article 3 bis of the aforementioned Chicago Convention). Beijing also charged that Washington had flown high-altitude balloons “over Chinese airspace over 10 times without authorization” since 2022—which begged the question why these intrusions were never formally protested by the Chinese military which controls the airspace. A US proposal for a telephone call between the US and Chinese defense chiefs to maintain lines of communication was declined, as per a communication on Feb. 8.

In the days and weeks following the incident, it emerged that both China and the United States maintain high-altitude balloon programs to exploit the domain of “near space” in the upper atmosphere (above 18 km or approximately 60,000 feet) for aerial surveillance, signals intelligence, and communications intercept purposes. Unlike satellites, balloons are quieter to launch and can loiter over a given location for extended durations and bridge a “capability gap between aircraft and satellites.” There is no record of the US Army’s Space and Missile Defense Command (USASMDC) flying high-altitude balloons into another country’s airspace, however, and as per an internal memo such military-operated or -commissioned balloons “are state aircraft under international law subject to the same requirements as other state aircraft.” This does invite the question whether US retrieval of the downed balloon’s payload, even in its own territorial waters, was a breach of the sovereign immune status of the airship.

Be that as it may, it has become increasingly clear that the Chinese “unmanned airship” was no mere civilian meteorological airship. It was 200-feet tall with solar panels, weighed more than 2,000 pounds, and was bristling with “a surveillance payload the size of a regional passenger jet.” For US intelligence agencies, the flight of the balloon was no surprise either. They had been aware of up to four additional Chinese spy balloons over recent years, as per a confidential National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) document that surfaced in the course of the Discord Leaks. The document states though that the government “has no imagery collection of the bottom of the [latest balloon’s] payload to analyze for an optical sensor,” suggesting a lack of detailed conclusions about the balloon’s surveillance capabilities and inviting questions regarding the decision to allow it to overfly the country. From the get-go though, President Biden was forthright that the shootdown decision was intended first, to protect lives beneath and thereafter to send a clear message that the “violation of our sovereignty is unacceptable.” He said he would be speaking to President Xi. That call has yet to materialize. At this time, Secretary Blinken’s postponed visit to Beijing is on hold as well.

Secretary Blinken and Wang Yi, director of the Office of the Central Commission for Foreign Affairs, did meet on the sidelines of the 59th Munich Security Conference in Germany on Feb. 18. The Chinese were quick to emphasize in their readout that the meeting was held at the request of the US side. The balloon incident, the Ukraine conflict, and peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait were key topics of the meeting. The US readout additionally underscored the importance of maintaining diplomatic dialogue and open lines of communication at all times. Whatever political traction the Munich meeting might have generated was quickly dissipated however by a “low confidence” but headline-making classified assessment by the US Energy Department, reported in The Wall Street Journal on Feb. 26, that the COVID-19 pandemic likely originated with a leak from a Chinese laboratory. The department had previously been undecided on the origins of the pandemic. Compounding this assessment was yet another intelligence report, dated late February and publicized soon after by Secretary Blinken, that China was actively considering providing weapons and ammunition to aid Moscow in its fight in Ukraine. Even though President Biden stepped in to refute the charge, saying that he did not expect China to send weapons to Russia in an interview with ABC News, the damage was done. In April, it emerged as part of the Discord Leaks that the Russian paramilitary group Wagner had sought munitions and equipment from China but was brushed aside. To date, no known sale of lethal arms has been made or found on the battlefield.

The Munich Security Conference also set the stage for a breakout moment in Chinese diplomacy. With a view to distancing itself from the stigma of its “no limits” characterization of ties with Russia and begin repairing its frayed relations with Europe, Wang Yi reached out directly in his conference keynote speech to the gathered Europeans. “China are Europe are two major forces, markets and civilizations in an increasingly multipolar world…if we choose peace and stability, a new Cold War will not break out,” he observed. The speech was followed by a 12-point policy statement listing “China’s Position on the Political Settlement of the Ukraine Crisis“ and the lending of its good offices to facilitate peace talks. This diplomatic facilitation was met with extreme skepticism in the West (although not by President Zelenskyy in Kyiv), especially in the wake of President Xi’s state visit to Moscow in late-March. On April 26, President Xi spoke with Zelenskyy for the first time since the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war and promised to “send the Special Representative of the Chinese Government on Eurasian Affairs…to have in-depth communication with all parties on the political settlement of the Ukraine crisis.” It remains to be seen what Li Hui, a fluent Russian speaker and ex-ambassador to Moscow, can produce on the peace facilitation front, but after Beijing’s surprising foray into Middle East relationship management featuring the Saudis and the Iranians, the effort cannot be entirely dismissed as a sham.

In parallel with its diplomatic audacity on the Ukraine front, the Chinese foreign ministry also laid out the core principles of President Xi Jinping’s Global Security Initiative (GSI), in a concept paper on Feb. 21. The GSI was first proposed by Xi at the Boao Forum in April 2022, two months after Russia’s aggression in Ukraine and presumably to forestall the splintering of major power international relations into a bloc-based format. The GSI’s contents are primarily the standard Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence fare, backed by 20 priority themes of cooperation. Not done yet with grand initiatives, on March 15, Xi unveiled a Global Civilization Initiative (GCI) to attendees at a High-level Dialogue between the Communist Party of China and World Political Parties.

The turbulent February period in US-China relations was also notable for an extraordinary series of bitter and denunciatory Chinese government reports, berating the United States for its drug abuse, gun violence, hegemonistic tendencies, and economic polarization. In the run-up to and during the Biden administration-led Summit for Democracy in late-March, the focus of disparagement was directed at the US state of democracy, its human rights violations, and arbitrary detention and home and abroad. This descent into smearing begs the question: would these reports and papers have been issued if the budding rapprochement—and, specifically, Secretary Blinken’s visit—had not been blown off-course by China’s wayward balloon? Constructive engagement and bitter diatribes don’t sit well together, one would imagine. “Zhong Sheng,” a homonym for “voice of China” and used by the People’s Daily to communicate the CCP’s views on international affairs, also remained active in its inimitable anti-American style, including in editorials prior to the postponement of Blinken visit.

The other major development in US-China relations during the first trimester of 2023 was the meeting between Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen and the Speaker of the US House of Representatives, Kevin McCarthy (R-California) at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in Simi Valley, California, during her transit on US soil on her trip to Guatemala and Belize. Transits by Taiwan’s leaders are hardly unusual; Tsai’s was the 29th such transit by a sitting Taiwanese president. Slightly more unusual was the duration of the transit—the length of the visit seemed more like a “private visit” than a “transit” (the former being disallowed as a norm by the US government since 1995). Tsai stopped in New York City from March 29-31 where she received the Hudson Institute’s Global Leadership Award; on her return leg from April 4-6, she was met by Speaker McCarthy and a host of Congresspersons and policy experts at the Reagan Library. Both institutions and their leaders were promptly sanctioned the day after her return by China’s foreign ministry under its Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law for facilitating Madame Tsai’s “Taiwan independence’ separatist activities” in the US. A number of Taiwanese organizations and government representative were also sanctioned. Later in April, in the rare instance of a senior US Congressperson being sanctioned, US Rep. Michael McCaul (R-Texas), chair of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, was barred from entry into China under the Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law for drawing a comparison between Xi Jinping and Adolf Hitler during his meeting in Taipei with Taiwan’s vice president.

The most precedent-worthy aspect of the Tsai transit was her meeting with McCarthy—the first such meeting between Taiwan’s President and a House speaker on US soil. Previous speakers have placed phone calls to transiting Taiwanese presidents and even participated in events hosted on Capitol Hill by Taiwan’s representative office in Washington, D.C.; none had met him or her in person. Still, one ought not make too much of the in-person meeting on US soil, especially since prior speakers paid visits to Taipei—Newt Gingrich in April 1997; Nancy Pelosi more recently in August 2022. On balance, Beijing appeared to bow to this reality. While working up indignation to protest McCarthy’s meeting with Tsai, the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) military exercises in the Taiwan Strait and East China Sea were a shadow of the August 2022 maneuvers conducted after the Pelosi visit—be it in terms of their provocation, intensity, or sophistication.

In August 2022, the PLA declared six closure zones around the island, blocked maritime trade for an entire week, and fired ballistic missiles over Taiwan, some of which landed in Japan’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). This time, the drills lasted three days and Beijing refrained from imposing a ring of missile-landing zones. The April 2023 drills, a combination of combat readiness patrols, joint air and sea operations, and live fire exercises off China’s Fujian province, also did not replicate the multistage war plan—firepower campaign, blockade, and invasion—executed after the Pelosi visit. The drills did not stray into Taiwan’s territorial waters either. That said, the PLAAF did fly a single-day record number of sorties during the three-day exercises, conducted numerous median line crossings, and the PLAN deployed its aircraft carrier, Shandong, to the East China Sea 230 km south of Japan’s Miyako Island in the Okinawa chain. To display resolve and restore deterrence, the USS Milius, a guided-missile destroyer, conducted a Taiwan Strait transit in international waters on April 16, the first such naval operation through the waterway since early January. In a rarer occurrence, a US Navy P-8A Poseidon maritime patrol and reconnaissance aircraft transited the Strait in international airspace on April 28. The last time a US warplane had overflown the Taiwan Strait was on Feb. 28, and before that only on June 24, 2022.

McCarthy has not ruled out a visit to Taiwan during his tenure as speaker of the 118th Congress. It is hard to see him do so in 2023, given the island’s cramped presidential election calendar. For its part, China managed to engineer the diplomatic defection of the Republic of Honduras from Taipei a mere few days before Tsai’s New York City stopover, with Tegucigalpa vowing in the Joint Communique that “Taiwan is an inalienable part of [the People’s Republic of] of China’s territory.” This pattern of poaching has form. Two days after Tsai returned from her California and Texas transits in August 2018, China scooped El Salvador up. It is worth noting that the Central American countries, including El Salvador and Honduras, had been Taipei’s staunchest backers at the San Francisco Peace Conference that seven decades ago set in train the geostrategic architecture of the Asia-Pacific region. Today, Guatemala and Belize are Taiwan’s only remaining diplomatic partners in Central America.

The Taiwan question was also at the center of US-PRC relations during this period—in no small part due to the incessant focus within the Beltway and beyond on the timing of a putative Chinese attack on the self-governing island. This fixation was kicked off by ex-US Indo-Pacific Command (USINDOPACOM) head, retired Adm. Philip Davidson, in March 2021 when—in testimony before the US Senate Armed Services Committee—he observed that the People’s Republic could take control of Taiwan “in the next six years.” Davidson attempted to walk back his observation somewhat, noting in an interview later that October that he had spoken as a strategist and not in his “role as the INDOPACOM commander” that day in March. Still, the 2027 timeline—labeled the “Davidson window”— spawned a cottage industry of invasion date speculation, including by senior uniformed officers. In October 2022, Adm. Mike Gilday, chief of naval operations, said that the US needed to prepare for possible action as early as 2023 and in January this year, Gen. Mike Minihan, former deputy Indo-Pacific commander, predicted that the US and China would probably go to war in 2025. To put a damper on such “guessing” talk, Adm. John Aquilino, commander of US forces in the Indo-Pacific—testifying before the Senate Armed Services Committee on April 20—declined to endorse any timeline of attack and focused his remarks on deterring “bad choice[s]” by China and President Xi.

Earlier in March, senior Biden administration civilian officials, testifying before Congress and elsewhere, had sought to inject greater depth and nuance to this invasion and unification hypothesis. At a Senate hearing on “evaluating US-China policy in the era of strategic competition,” Assistant Secretary of Defense for Indo-Pacific Security Affairs Ely Ratner observed that an invasion of Taiwan was not “imminent or inevitable.” The US and Taiwan can certainly “get to the end of this decade without [the People’s Republic] committing major aggression against Taiwan,” he maintained. During testimony on Capitol Hill in early March, Director of National Intelligence (DNI) Avril Haines, assessed that Beijing did not want to go to war. It would only opt for war if “they believe peaceful unification is not an option,” she postulated. More broadly, Beijing was still invested in “preserving stability in its relationship with the United States,” despite sharp criticism of Washington by Xi at the “Two Sessions” meeting that coincided at that time. (The Two Sessions meeting itself did not produce any new policy initiatives or phraseology on Taiwan, sticking instead to a recitation of well-worn positions.) Separately, in April, William Burns, Director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), chimed in during an appearance at Rice University’s Baker Institute that there was no evidence to suggest that Xi had made a decision to invade Taiwan. While he is utterly committed to unification and had instructed the PLA to be ready by 2027 to successfully invade Taiwan, “being ready does not mean that he’s made the decision to go to war in 2027 or 2028 or 2026, but it’s something that we need to take very seriously as well,” Burns noted.

US arms sales to Taiwan continued on their set path during the first trimester of 2023. On March 1, Congress received notification of potential sale of $619 million worth of F-16 fighter jet munitions, including 100 AGM-88B High-Speed Anti-Radiation Missiles (HARM), 200 AIM-120C-8 Advanced Medium Range Air-to-Air Missiles (AMRAAM), four AIM-120C-8 AMRAAM guidance systems, and 26 LAU-129 multipurpose launchers. Once approved by Congress, the package would mark the first sale to Taiwan of AIM-120C-8 missiles, which are fielded on advanced US jets and feature a greatly increased range over its predecessor. In mid-April, it was reported that a contract with Boeing was issued on Taiwan’s behalf by the US Naval Air Systems Command for 400 land-launched Harpoon missiles, completing a deal approved by Congress in 2020. It marks the first sale of the mobile, land-launched version of the missile; the ship-launched version already exists within the Taiwanese military’s inventory.

The arms sales, while intended to assist the island to maintain a sufficient self-defense capability, don’t sit well with Beijing. Beijing moved on its (usually empty) threat to impose sanctions to actually imposing sanctions, however symbolic, on offending parties involved in an arms sale package. Replying to questions on April 18 on the implementation of its Unreliable Entities List Working Mechanism, China’s Ministry of Commerce announced that six senior executives from Lockheed Martin and Raytheon Missile and Defense would be barred from entering or working in China, and that the two companies were prohibited from engaging in People’s Republic-related import and export activities. Both companies had been placed on the Unreliable Entities List in February, the first instance of placement of any company on that list. In September 2022, Raytheon Missile and Defense had been awarded a $412 million contract to upgrade Taiwan’s military radar as part of a larger $1.1 billion arms package. Raytheon Technologies, the parent firm which sells its Pratt & Whitney aircraft engine as well as landing gear and controls to China’s commercial aviation industry, was not sanctioned. The Wall Street Journal also reported in Feb. that Washington planned to scale up its rotational deployment on the island from 27 troops in December 2022 (as per the Pentagon’s Defense Manpower Data Center website) to between “100 and 200 troops…in the coming months.” A uniformed US presence on the island is a touchy subject in US-China relations.

There were a number of other notable developments with direct and indirect geostrategic implications for relations with China. On March 13, President Biden flanked by United Kingdom Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese in San Diego, listed the AUKUS partnership’s project milestones related to Canberra’s acquisition of a conventionally-armed, nuclear-powered submarine capability. On March 16, the State Department approved the sale of 220 Tomahawk cruise missiles to Australia, a transfer that would exceed the prescribed payload and range limits of Category I systems listed in the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) Annex. The MTCR maintains a strong “presumption of denial” but not an outright prohibition on such transfers. On April 4, the US and the Philippines announced plans to expand Enhanced Defense Cooperation Arrangement (EDCA) to include four new sites, including ones located in close proximity to the strategically vital Bashi Channel. On April 26, Biden and South Korea’s Yoon Suk Yeol pledged to coordinate more deeply on nuclear response strategy—although not “nuclear share”—on the Korean Peninsula, including establishing a new Nuclear Consultative Group (NCG) to strengthen strategic planning. A US nuclear-armed submarine will also dock in South Korea for the first time in over four decades. And finally, also in late-April, the US Defense Department released its Annual Freedom of Navigation Report for Fiscal Year 2022. The People’s Republic of China was challenged for the largest number of excessive maritime claims. Freedom of navigation assertions were also conducted in the South China Sea on March 23 (near the Paracel Islands) and on April 9 (near Mischief Reef in the Spratlys) by the US Navy’s 7th Fleet, and were met by rebukes from China’s Southern Theater Command.

Two important speeches were delivered by senior officials in late-April that bookend the Biden administration’s economic approach to China. On April 20, almost exactly a year to the day that she delivered an important speech on “favoring the “friend-shoring” of supply chains to a large number of trusted countries,” Treasury Secretary Yellen stepped to the podium and called this time for a “healthy economic engagement that benefits both [the United States and China].” The “world is big enough for both of us,” she declared with an outstretched hand, and Beijing and Washington needed to “find a way to live together and share in global prosperity.” National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan was less charitable in remarks a week later, noting that Beijing had become neither “more responsible or cooperative, and ignoring economic dependencies that had built up over decades of liberalization had become really perilous.” NSA Sullivan’s speech was directed in any case at the US’s favored set of “like-minded” friendshoring partners in the developed and developing world; it was not meant as an outreach to China.

The mixed messaging is emblematic of the Biden administration’s approach on China. Like fellow Cabinet appointees Gina Raimondo (Commerce) and Katherine Tai (US Trade Representative), Yellen was at pains to stress that the administration had imposed its technology denial measures for national security and not unfair economic competitiveness reasons, that it was not seeking to stifle China’s development or decouple from it, and that she looked forward to travelling to Beijing at the “appropriate time.” On the other hand, the steady stream of “economic suppression” measures (in Beijing’s eyes) continued unabated. On March 23, the Commerce Department published a proposed rule that sets tall guardrails against the flow of any CHIPS for America Incentives Program money from bleeding into the Chinese semiconductor ecosystem. On March 31, the Treasury Department released proposed guidance on the Inflation Reduction Act’s new clean energy vehicles consumer subsidy that will effectively bar Chinese EV’s and EV components from the American marketplace. Earlier in March, a number of Chinese firms were consigned to the Commerce Department’s Entity List for their contributions to Beijing military-civil fusion strategy as well as surveillance and repression of ethnic minorities in China. It includes the biotech research firm BGI Tech Solutions (entities associated with the high-altitude surveillance balloon program were sanctioned in mid-February, and suppliers of precursor chemicals for fentanyl production placed on the Treasury Department’s Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List in mid-April).

Executive action is awaited on an outbound investment screening mechanism that will impose a notification requirement or outright bar capital or technology transfer participation in China’s semiconductor, artificial intelligence, and quantum computing sectors. And on Capitol Hill, legislative text is being finalized with the administration’s assent that will empower the Commerce Secretary to review, block, and mitigate a range of adversary ecommerce platforms and social media applications, including most notably TikTok. The Section 301 tariffs on Chinese imports continue to fester too, although they appear to have done little in narrowing the gargantuan trade deficit with Beijing.

For its part, China has not been sitting still. Though professing to maintain open lines of communication, not a single senior-level economic official visit is on the anvil. China has within the past few weeks opened a cybersecurity review of the US chip firm Micron, rewritten and broadened its espionage law, raided the local office of the US due-diligence firm Mintz Group, let it be known that TikTok’s algorithm is covered by China’s export control laws and hence unprocurable through foreign acquisition, and is in the process of adding high-performance rare earth magnets to its revised Catalogue of Technologies Prohibited and Restricted from Export to protect “national security” and the “public interest of society.” There will be more countermeasures. Moreover, at the Two Sessions meeting in early-March, a root-and-branch institutional reorganization of government focused on the technology, finance and data sectors was instituted, to help compete against and counter US economic suppression measures.

The balloon incident continues to cast a pall over US-China relations. Beijing remains leery of scheduling high-level meetings with its counterparts, lest the US release the incident report at or immediately after the scheduled meeting and embarrass China by confirming the obvious—that the balloon was no civilian weather airship but a military-commissioned high-altitude surveillance balloon. Even working-level dialogues remain impacted, with the defense side ones in particular—the Defense Policy Coordination Talks; Military Maritime Consultative Agreement Mechanism meetings—unlikely to start anytime soon. That the Pentagon point person for Beijing, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for China, Taiwan and Mongolia Michael Chase, paid a quiet visit to Taipei in February—only the second such visit by a senior defense official in many decades—has added a wrinkle. That said, the balloon incident is likely not the only explanation, though it may be the justification, for China’s reticence to talk. With its relations with Brussels thawing and with Washington confronted by financial market instability and recession talk as well as impending debt-ceiling challenges, Beijing may be playing harder to get now that it feels reasonably assured that the US side is genuinely committed to setting a “floor” under the relationship. Where this leaves the erecting of guardrails as envisaged at the Biden-Xi meeting in Bali, only time will tell.

January – April 2023

This chronology was prepared by Alec Caruana, ICAS Part-Time Research Assistant.

Jan. 2, 2023: Chinese Foreign Minister Qin Gang departs Washington after his tenure as Chinese ambassador to the US ends.

Jan. 5, 2023: US 7th Fleet Destroyer USS Chung-Hoon transits the Taiwan Strait.

Jan. 9, 2023: A proposed phone call between Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin and Chinese Defense Minister Wei Fenghe is canceled after the Chinese decline to participate.

Jan. 10, 2023: US House of Representatives votes to establish a Select Committee on Strategic Competition between the United States and the Chinese Communist Party.

Jan. 12, 2023: US Special Climate Envoy John Kerry meets virtually with Chinese counterpart Xie Zhenhua.

Jan. 16, 2023: China conducts live-fire exercises in the South China Sea as the US Navy’s Nimitz Carrier Strike Group also transits the waters.

Jan. 18, 2023: US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has a “candid, substantive, and constructive conversation” with Vice-Premier Liu He on the sidelines of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland.

Jan. 19, 2023: US Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for China Michael Chase speaks to Song Yanchao, deputy director of China’s Office for International Military Cooperation, to express US “red-lines” on the Ukraine War ahead of a scheduled visit to China by Secretary of State Antony Blinken.

Jan. 22, 2023: Director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, Dr. Rahul Gupta, tells the Financial Times that his office is increasing pressure on Beijing to crack down on precursor chemicals used to create fentanyl while highlighting the potential for the drug crisis to spread to Europe and Asia.

Jan. 26, 2023: President Biden extends a program that allows for Hong Kong residents to remain in the US, citing the erosion of human rights and freedoms.

Jan. 27, 2023: United States Marine Corps opens a new base on Guam to counter China’s presence in the Western Pacific.

Jan. 27, 2023: US Trade Representative appeals two WTO dispute panel rulings brought by China on Section 232 tariffs and on “made in China” designations for Hong Kong to a defunct WTO Appellate Body.

Jan. 27, 2023: Air Force Gen. Mike Minihan warns in a leaked internal memo to US military leadership that the US and China “will fight in 2025” over Taiwan. The Pentagon immediately distances itself from the comments saying they are “not representative of the department’s view on China.”

Jan. 31, 2023: US Customs and Border Protection begins to issue detention notices against aluminum shipments originating in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region over concerns of forced labor.

Jan. 31, 2023: US stops approving export licenses bound for Huawei.

Jan. 31, 2023: Undersecretary for Defense Policy Colin Kahl dismisses Gen. Minihan’s leaked assessment for Taiwan saying “I don’t see anything that indicates that this thing is imminent in the next couple of years.”

Jan. 31–Feb. 4, 2023: A Chinese surveillance balloon floats across the continental United States after first being spotted over Alaska on Jan. 28.

Feb. 1, 2023: House Committee on Energy and Commerce holds a hearing entitled “Economic Danger Zone: How America Competes To Win The Future Versus China.”

Feb. 2, 2023: US reopens its embassy in the Solomon Islands with Secretary Blinken hailing it as an important signal of Washington’s commitment to democracy in the Pacific region.

Feb. 2, 2023: Defense Secretary Austin reaches agreement with Philippine President Bongbong Marcos to expand the rotational US military presence in the Philippines with reference to confronting China in the South China Sea.

Feb. 2, 2023: Pentagon publicly announces that a high-altitude surveillance balloon from the People’s Republic of China is present above Montana.

Feb. 2, 2023: At an event at Georgetown University, CIA Director William Burns warns not to underestimate China’s ambitions toward Taiwan and that the agency knows “as a matter of intelligence” that President Xi has instructed the military to be operationally ready to reclaim Taiwan by 2027.

Feb. 3, 2023: Department of State indefinitely postpones Secretary Blinken’s planned visit to China over the balloon incident.

Feb. 4, 2023: China acknowledges the “unintended entry of a Chinese unmanned airship into US airspace due to force majeure.”

Feb. 4, 2023: US shoots down the surveillance balloon over the coast of South Carolina.

Feb. 6, 2023: China protests the downing of the balloon with the US Embassy in Beijing.

Feb. 7, 2023: President Biden vows to respond to Chinese threats to US sovereignty in his State of the Union address.

Feb. 7, 2023: House Financial Services Committee holds a hearing entitled “Combatting the Economic Threat from China.”

Feb. 7, 2023: House Armed Services Committee holds a hearing entitled “The Pressing Threat of the Chinese Communist Party to US National Defense.”

Feb. 8, 2023: Pentagon describes the downed balloon as part of a wider, global Chinese surveillance operation.

Feb. 9, 2023: Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on the Defense Deptartment holds a hearing on “The People’s Republic of China’s High Altitude Surveillance Efforts Against the United States.”

Feb. 9, 2023: Beijing’s state-owned Xinhua news issues a report decrying the level of drug abuse in the US.

Feb. 10, 2023: Department of Commerce adds six Chinese companies to the Entity List over their involvement in Beijing’s balloon surveillance program.

Feb. 11, 2023: US Navy’s Nimitz Carrier Strike Group conducts combined exercises in the South China Sea with the Marine Corps” Makin Island Amphibious Ready Group.

Feb. 13, 2023: China alleges that the US sent 10 balloons into Chinese airspace in 2022.

Feb. 15, 2023: Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman says that all countries should warn China against invading Taiwan at an event at the Brookings Institution.

Feb. 15, 2023: US Defense official anonymously confirms that the planned trajectory of the downed Chinese surveillance balloon would likely have taken it over Guam and Hawaii rather than the continental United States.

Feb. 16, 2023: Beijing’s state-owned Xinhua news organ issues a report decrying gun violence in the US.

Feb. 17, 2023: China imposes sanctions on US defense manufacturers Raytheon and Lockheed Martin as a “countermeasure” for their fulfillment of arms sales contracts for Taiwan.

Feb. 18, 2023: Wang Yi, Politburo member and director of the Office of the Central Commission for Foreign Affairs, delivers keynote remarks titled “Making the World a Safer Place” at the 59th Munich Security Conference in Germany.

Feb. 18, 2023: In an effort to maintain lines of communication, Secretary Blinken meets Wang Yi on the sidelines of the 59th Munich Security Conference, the first high-level meeting between Chinese and US officials since the balloon incident. Maintaining a cold shoulder, the Chinese readout is explicit that the meeting comes at the request of the US side.

Feb. 19–22, 2023: Ranking members of the House Select Committee on China, Mike Gallagher and Ro Khanna, travel to Taiwan as part of two delegations and issue a statement against China’s “cognitive war” against Taiwan upon their return.

Feb. 20, 2023: Beijing’s state-owned Xinhua news organ issues a report decrying US “hegemony” across the world’s political, military, economic, technological and cultural spheres.

Feb. 22, 2023: China launches a new concept paper for the “Global Security Initiative” which appends 20 “priorities of cooperation” to its standard sovereignty-focused fare.

Feb. 22, 2023: A Chinese J-11 fighter jet shadows a US Navy reconnaissance plane over the South China Sea.

Feb. 23, 2023: Beijing’s state-owned Xinhua news organ issues a report decrying economic polarization in the US.

Feb. 24, 2023: Office of the US Trade Representative releases an annual report on China’s WTO Compliance.

Feb. 24, 2023: Beijing issues a 12-point “Political Settlement of the Ukraine Crisis” which US officials are quick to dismiss as “talking up Russia’s false narrative about the war.” Secretary Blinken tells ABC News that China’s peace plan is not serious as “if they were serious about the first [point], sovereignty, then this war could end tomorrow.”

Feb. 26, 2023: CIA Director William Burns, in a revision of comments from earlier in the month, assesses that China likely has doubts about its ability to invade Taiwan and that Xi’s 2027 target to be invasion-ready is not indicative of a solid decision.

Feb. 26, 2023: Updated Department of Energy report concludes, albeit with a low level of confidence, that the COVID-19 pandemic emerged as a leak from the Wuhan Institute of Virology’s research into the novel coronavirus.

Feb. 27, 2023: A US 7th Fleet P-8A Poseidon aircraft transits the Taiwan Strait.

Feb. 28, 2023: An inaugural hearing of the House Select Committee on China is held on “The Chinese Communist Party’s Threat to America.”

Feb. 28, 2023: House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology holds a hearing on “United States, China and the Fight for Global Leadership: Building a U.S National Science and Technology Strategy.”

Feb. 28, 2023: House Foreign Affairs Committee holds a hearing on “Combatting the Generational Challenge of CCP Aggression.”

March 2, 2023: Department of Commerce adds 28 Chinese firms to the Entity List over alleged ties to the Iranian military.

March 6, 2023: President Xi, in rare form, takes direct aim at US “containment, encirclement and suppression” of China in a speech at the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference.

March 7, 2023: White House endorses introduction of the RESTRICT Act in the Senate, which would empower the Commerce Dept. to ban technology services and service providers deemed to pose “undue or unacceptable risk” to US national security from the country.

March 8, 2023: US Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines tells lawmakers at a hearing of the Senate Intelligence Committee that the Chinese government is seeking to avoid further escalation of bilateral tensions and emphasized China’s desire for a more stable relationship.

March 8, 2023: House Judiciary Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual Property and the Internet holds a hearing entitled “Intellectual Property and Strategic Competition with China: Part I.”

March 9, 2023: House Homeland Security Subcommittee on Counterterrorism, Law Enforcement, and Intelligence holds a hearing on “Confronting Threats Posed by the Chinese Communist Party to the US Homeland.”

March 13, 2023: President Biden announces project milestones and timelines related to a landmark agreement to jointly develop and deploy nuclear submarines in the Asia-Pacific region with Australia and the United Kingdom.

March 20, 2023: Biden signs a law requiring his administration to declassify US intelligence on the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic.

March 20, 2023: China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs issues a report decrying the state of US democracy in 2022.

March 21, 2023: Department of Commerce issues a proposed rule to restrict foreign firms from using CHIPS and Science Act grants to expand semiconductor manufacturing capacity overseas.

March 23, 2023: TikTok CEO Shou Zi Chew testifies before House Committee on Energy and Commerce and is questioned on the company’s firewall and data protection policies. Following the hearing, the Chinese Foreign Ministry clarifies in a press conference that China does not ask any company for access to foreign data.

March 23, 2023: House Select Committee on China holds a hearing entitled “The Chinese Communist Party’s Ongoing Uyghur Genocide.”

March 23, 2023: House Financial Services Subcommittee on National Security, Illicit Finance, and International Financial Institutions holds a hearing entitled “Follow the Money: CCP’s Business Model Fueling the Fentanyl Crisis.”

March 24, 2023: US 7th Fleet Destroyer USS Milius conducts a Freedom of Navigation Operation in the Paracel Islands.

March 28, 2023: China’s State Council Information Office issues a report decrying the level of human rights violations in the US in 2022.

March 29, 2023: Beijing’s state-owned Xinhua news issues a report decrying US arbitrary detention practices at home and abroad.

March 29–31, 2023: Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen transits New York on her way to Central America where she receives a Global Leadership Award from the Hudson Institute.

March 31, 2023: Treasury Department releases proposed guidance on the electric vehicle consumer subsidy found in the Inflation Reduction Act which will effectively ban Chinese EVs and EV battery components from the US market.

April 3, 2023: Washington and Manila jointly announce the locations of four more military bases with US funding and troop access—three of which are located in the north of the country near Taiwan, and one in the southwest near the Spratly islands. China’s foreign ministry responds on the 6th, saying that the new locations are “uncalled-for.”

April 4-6, 2023: Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen stops in California, en-route from visits to Guatemala and Belize, where she meets House Speaker Kevin McCarthy and several other US lawmakers at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library. China responds on the 7th by sanctioning the US institutions and individuals who met Tsai, and sending aircraft and warships across the Taiwan Strait for a 3-day exercise “encircling” the island.

April 6-8, 2023: House Foreign Affairs Committee Chairman Michael McCaul visits Taiwan and meets Tsai and Vice President Lai Ching-te. On the 13th, China responds by sanctioning him personally, adding to the list of senior members of Congress on Beijing’s blacklist.

April 7, 2023: Leaked documents from the Pentagon come to light and expose US military intelligence’s apprehension about Taiwan’s ability to accurately detect and quickly counter potential Chinese air strikes. The leaks also reveal that, as of January, China ignored all requests from Russia’s Wagner Group to provide weapons for its military actions in Ukraine.

April 8, 2023: House of Representatives votes unanimously to instruct the White House to work toward changing China’s status as a “developing nation” in the World Trade Organization.

April 9, 2023: US 7th Fleet Destroyer USS Milius conducts a Freedom of Navigation Operation near the Beijing-controlled Mischief Reef in the Spratly Islands.

April 11, 2023: Washington and Manila agree to move forward with drafting a “Security Sector Assistance Roadmap,” with a focus on resisting Chinese incursions in the South China Sea, at a 2+2 (defense and foreign) ministerial dialogue in Washington.

April 12, 2023: Government Accountability Office releases a report entitled “Federal Spending: Information on US Funding to Entities Located in China.”

April 14, 2023: Treasury Department sanctions two entities and four individuals from China over their involvement in supplying precursors for US-bound fentanyl.

April 15, 2023: China refuses to reschedule Secretary Blinken’s planned visit to Beijing over concerns that the FBI may release to the public the results of its analysis of the debris recovered from the Chinese surveillance balloon downed in early February.

April 16, 2023: US 7th Fleet Destroyer USS Milius transits the Taiwan Strait.

April 17, 2023: Foreign ministers of the G7 countries meet in Japan and vow, among other things, to address China’s increasing threats to Taiwan and ambiguity on the war in Ukraine.

April 18, 2023: Adm. John Aquilino, senior US military commander in the Indo-Pacific, dismisses colleagues’ speculations about a potential timetable for a Chinese invasion of Taiwan in testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee.

April 18, 2023: House Oversight and Accountability Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic holds a hearing entitled “Investigating the Origins of COVID-19, Part 2: China and the Available Intelligence.”

April 18, 2023: House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Indo-Pacific holds a hearing entitled “Surrounding the Ocean: PRC Influence in the Indian Ocean.”

April 18, 2023: House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Africa holds a hearing entitled “Great Power Competition in Africa: Chinese Communist Party.”

April 18, 2023: House Ways and Means Subcommittee on Trade holds a hearing entitled “Countering China’s Trade and Investment Agenda: Opportunities for American Leadership.”

April 19, 2023: House Committee on Ways and Means holds a hearing entitled “The US Tax Code Subsidizing Green Corporate Handouts and the Chinese Communist Party.”

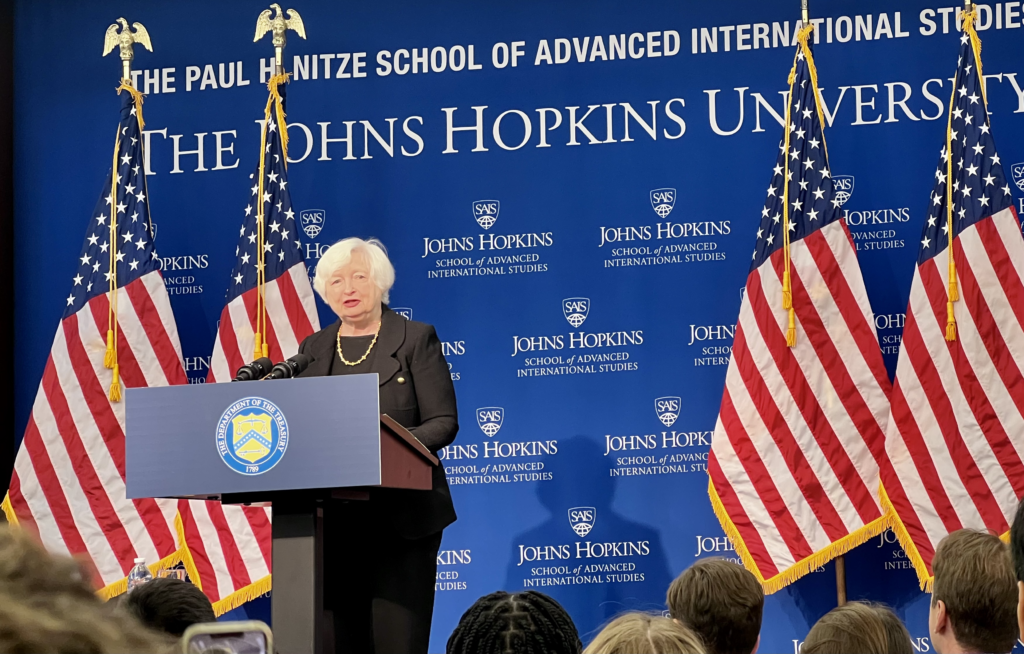

April 20, 2023: Secretary Yellen gives a speech at Johns Hopkins University that presents a softer economic approach to China than seen in months previous. It seeks “a constructive and fair economic relationship with China” which aims to close gaps in US national security through “friendshoring…creating redundancies in our critical supply chains” without “a full separation of [the two] economies” or “stifl[ing] China’s economic and technological modernization.”

April 20, 2023: US Army Maj. Gen. in Japan Joel Vowell states that Tokyo has shifted its military focus to protecting the Ryukyu Island chain in its southwest against potential threats from China, and that the US is aiding in this pivot.

April 20, 2023: House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Global Health, Global Human Rights, and International Organizations holds a hearing entitled “China’s Political Prisoners: Where’s Gao Zhisheng?”

April 20, 2023: Department of Homeland Security announces commencement of a 90-day, AI-integrated review of Chinese influence in US supply chains and firms.

April 21, 2023: Pentagon releases Annual Freedom of Navigation Program Report for Fiscal Year 2022 which lists China as the country with the most transgressions of international laws which govern maritime claims and navigational rights.

April 22, 2023: House Select Committee on China holds tabletop exercise that simulates a Chinese attack against Taiwan to review US policy options in a worst-case scenario.

April 26, 2023: House Oversight and Accountability Subcommittee on Health Care and Financial Services holds a hearing entitled “China in Our Backyard: How Chinese Money Laundering Organizations Enrich the Cartels.”

April 26, 2023: President Xi speaks on the phone with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy for the first time, with the latter welcoming China’s substantive step in facilitating a political end to the conflict despite Washington’s apprehension.

April 26, 2023: Biden administration agrees to send a nuclear ballistic missile-armed submarine, and other “strategic assets,” to South Korea during a state visit by President Yoon Suk-yeol to Washington. Beijing angrily responds the next day calling it the product of Washington’s “selfish geopolitical interests” that undermines “regional peace and stability.”

April 27, 2023: National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan delivers remarks to the Brookings Institution elaborating on Yellen’s speech on China-implicated economic policy the previous week. He clarifies that the administration’s “modern trade agreements” with “like-minded partners” will include more than just tariff reduction, adding supply chain resilience, green finance, and labor rights to the list of US economic interests.

April 27, 2023: House Armed Services Subcommittee on Intelligence and Special Operations holds a hearing entitled “A Review of the Defense Intelligence Enterprise’s posture and capabilities in strategic competition and in synchronizing intelligence efforts to counter the People’s Republic of China.”

April 27, 2023: A US 7th Fleet P-8A Poseidon aircraft transits the Taiwan Strait.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2026 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Project Vault and the Upstream Turn in U.S.–China Competition