First emerging as an acknowledged field of study as part of a 2009 United Nations Environment Programme report in recognition that the ocean plays a role as earth’s largest carbon sink, “blue carbon” has been recognized as a crucial, natural way to sequester carbon and conserve marine ecosystems in the long-term. ‘Blue carbon’ refers to the habitats, species, and processes that sequester carbon into deep sediments or deep waters in both coastal and open ocean ecosystems. According to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, coastal blue carbon ecosystems (which includes seagrasses, salt marshes, and mangroves) “store three-to-five times more carbon per unit area than tropical forests, and [sequester]carbon at a rate ten times greater than tropical forests”.

There is still debate as to what processes should constitute deep sea blue carbon, including its measurement, as sequestration does not occur in situ in open waters. However, the scientific community generally acknowledges that it is important not to limit blue carbon policy and management to coastal blue carbon alone, as deep-sea ecosystems do play an immense role in capturing carbon, though its full extent is not yet entirely understood. Without including blue carbon resources as part of a country’s carbon emissions stock, the nationally determined contributions of each signatory of the 2015 Paris Agreement will be inadequately measured. Thus, marine protected areas (MPA) have been discussed as necessary for the conservation of blue carbon resources in both coastal and deep-sea ecosystems. Numerous successful examples of MPAs within national borders garner some hope for increased implementation, yet outside national borders or in areas of disagreement, the situation is cloudier.

Fortunately, despite its relative nascency as an internationally recognized field of study, there has been significant multilateral cooperative efforts in addressing the need to better incorporate blue carbon as a necessary topic of discussion. 2019 marked the first year in which ocean issues were put at the front and center of climate action, which was marked by Chile hosting the first ‘blue’ Conference of the Parties (COP25) in Madrid, Spain. A delegation led by the United States, the United Kingdom, Chile, France, and Costa Rica elevated the role that MPAs can play in climate change mitigation and outlined the need for blue carbon to be incorporated into countries’ nationally determined contributions. The result of these conversations led to the establishment of the International Partnership on MPAs, Biodiversity and Climate Change. During COP26 in Glasgow, the Partnership further raised the profile of MPAs by providing expertise and lessons learned from the respective member countries.

This new partnership has the potential to link numerous regions of the world together to develop best practices in conservation policy based on the best available science. Such collaborative efforts should be built out further so that Asia, Africa, and other regions can also participate and be involved. As a result of its efforts, in addition to other representative countries taking part in COP26, the Glasgow Climate Pact that was adopted under the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change now recognizes ocean-based actions as essential to addressing climate change. It also requires that an annual dialogue be held every May or June from 2022 onward to report back to the COP each year. Yet, the road to effective MPAs outside of national borders is fraught with danger, particularly in regions of continued dispute.

As maritime disputes take an overwhelming amount of bandwidth in the international relations and policy community, it is essential that the scientific community find ways to remain a prominent part of the conversation. With intensifying situations in regions like the South China Sea, the scientific community has an opportunity to play a mitigating role. However, extreme caution must be taken. Even environmental science and conservation efforts can be co-opted to serve political interests at the expense of actual progress. Unilaterally declaring MPAs have the potential to exacerbate marine conflicts rather than solve them.

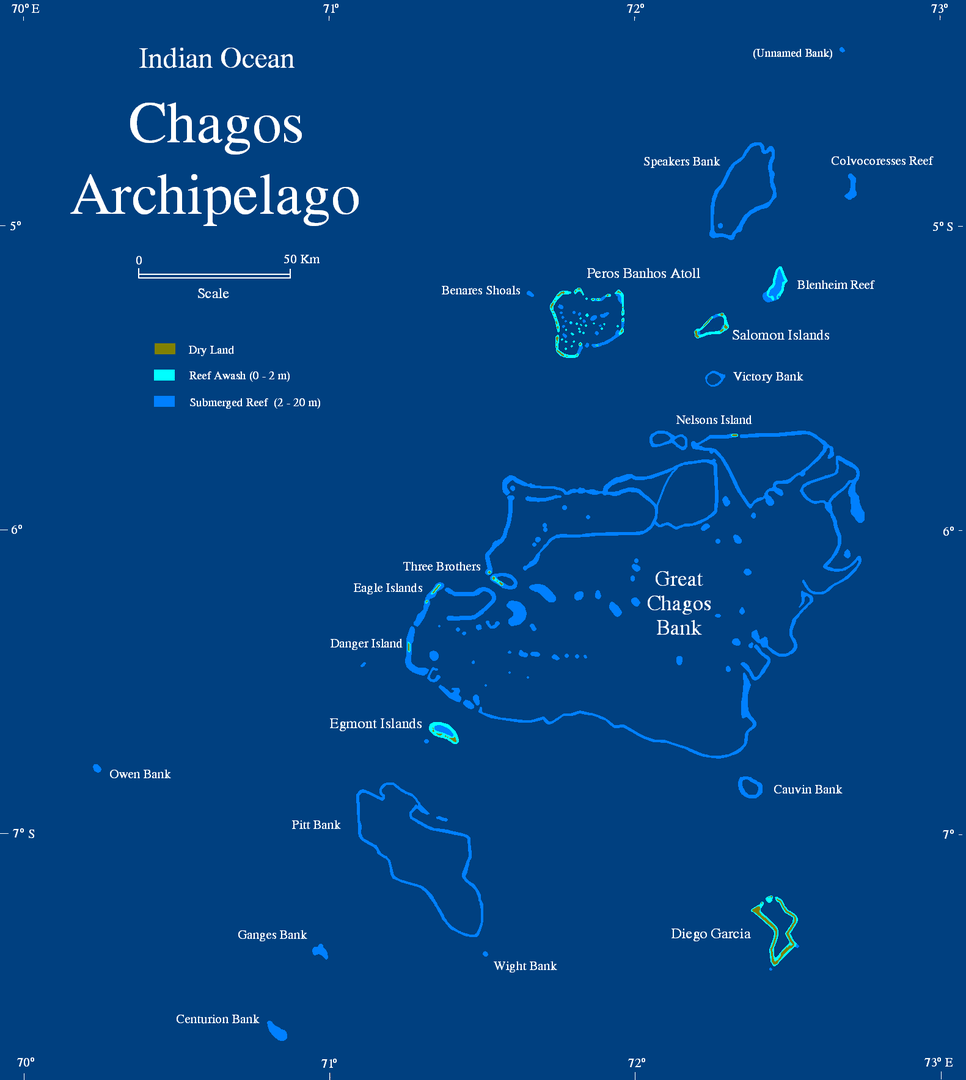

Take the case of the Chagos Archipelago. On April 1, 2010, the United Kingdom unilaterally established an MPA around the Chagos Archipelago, which extended 200 nautical miles from its baselines and covered an area of half a million square kilometers. The archipelago, which has been the subject of a decades-long sovereignty dispute between the UK and Mauritius, has also housed a joint UK/US Naval base on its largest island of Diego Garcia since the early 1970s. As a result of the MPA declaration, the Mauritian government launched an arbitral tribunal with the Hague which ruled against the UK in 2015, arguing that its establishment violated international law as set out by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Even further, it was discovered, according to Wikileaks CableGate documents, that the UK had established this MPA for political reasons in order to prevent the archipelago’s former inhabitants from being able to return. As of 2021, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea concluded that the UK has no legal sovereignty over the Islands and should return them to Mauritius—a position that the UK rejects to this day.

Although this is only one such high profile example, incidents such as this serve to greenwash and undermine international trust, thus ruining the potential effectiveness that MPAs could achieve through conservation of their blue carbon resources. Countries will be less likely to apply MPAs as a potential mechanism to not only achieve carbon emission goals, but potentially shelving tensions in highly disputed waters like the South China Sea. However, if blue carbon resources are to be adequately conserved in both coastal and open sea ecosystems, as well as applied to the nationally determined contributions of Paris Agreement signatories, MPAs must be negotiated through bilateral or multilateral agreements. Otherwise, MPAs will simply become another mechanism for a state to impose its claims in contested waters. This is the great potential danger that is at the brink of irreversibly passing into common custom if the issue is not given enough attention.

This Spotlight was originally released with Volume 1, Issue 3 of the ICAS MAP Handbill, published on April 26, 2022.

This issue’s Spotlight was written by Matt Geraci, ICAS Research Associate & Manager, Blue Carbon & Climate Change Program.

Maritime Affairs Program Spotlights are a short-form written background and analysis of a specific issue related to maritime affairs, which changes with each issue. The goal of the Spotlight is to help our readers quickly and accurately understand the basic background of a vital topic in maritime affairs and how that topic relates to ongoing developments today.

There is a new Spotlight released with each issue of the ICAS Maritime Affairs Program (MAP) Handbill – a regular newsletter released the last Tuesday of every month that highlights the major news stories, research products, analyses, and events occurring in or with regard to the global maritime domain during the past month.

ICAS Maritime Affairs Handbill (online ISSN 2837-3901, print ISSN 2837-3871) is published the last Tuesday of the month throughout the year at 1919 M St NW, Suite 310, Washington, DC 20036.

The online version of ICAS Maritime Affairs Handbill can be found at chinaus-icas.org/icas-maritime-affairs-program/map-handbill/.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2026 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.