The ‘nine-dash line’ is one of many names for a controversial Chinese maritime claim in the South China Sea. Though the claim is a matter of consistent discussion in the law of the sea community, it is often hard to make heads or tails of it in the national conversation due to the sensational headlines and veil of technical esotericism which surround it. That being said, with a bit of nuance and background information, this issue can hopefully become more accessible as important discussions over South China Sea claims and their associated rights and obligations continue in the coming years.

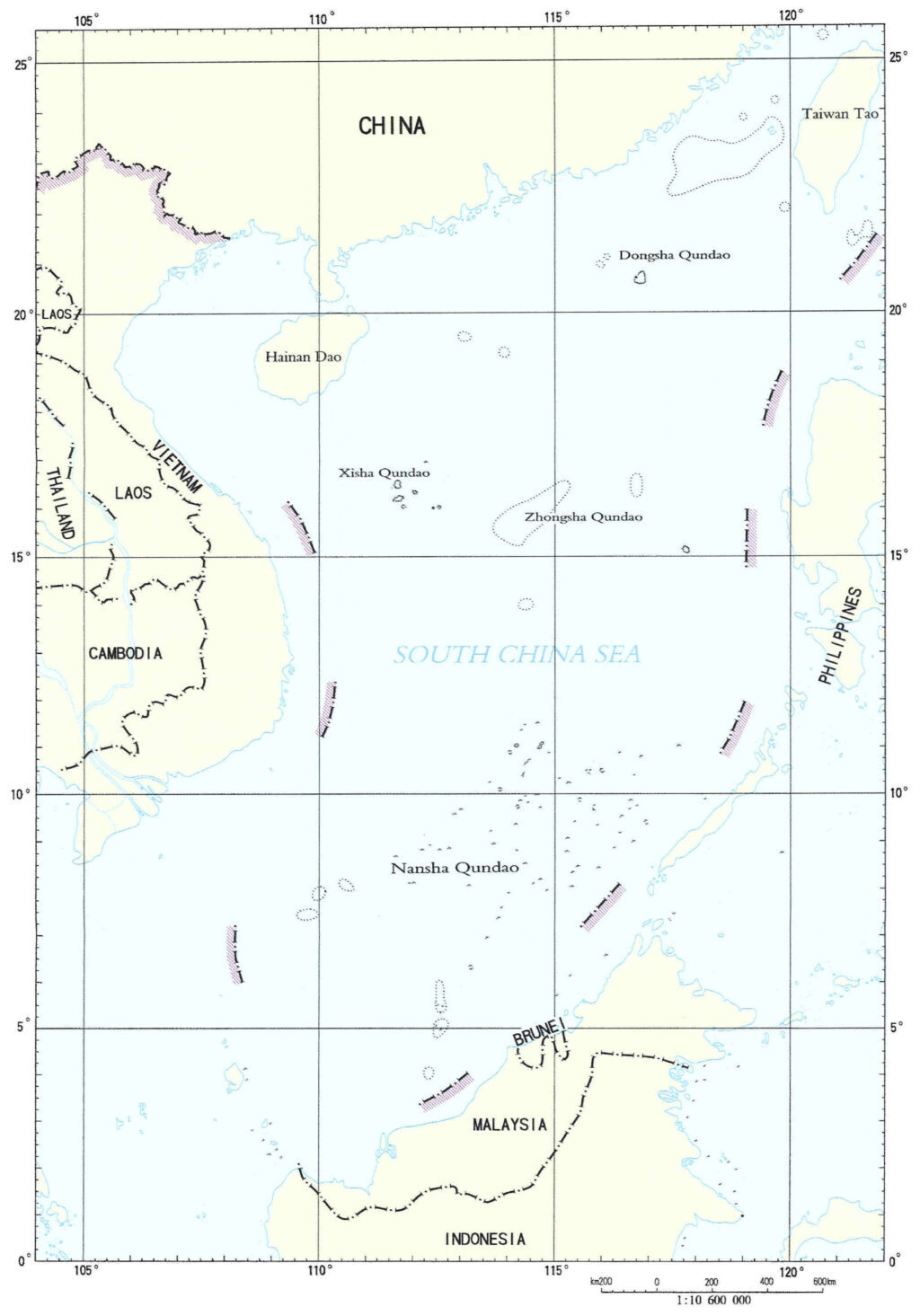

Broadly speaking, the nine-dash line (also known as the eleven-dash line, the U-shaped line, and the dotted line) is a visual representation of China’s claims that appears on some Chinese official maps and comparative maps of disputed claims in the South China Sea. While it is often understood that the line signals the limits of Chinese territory writ large, this interpretation is an oversimplification that enjoys little support among Chinese scholars. Rather, Beijing today employs the dashed line to outline (a) the islands and rocks in the South China Sea over which China asserts territorial sovereignty, (b) the maritime zones governed by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (i.e. territorial sea, contiguous zone, exclusive economic zone, continental shelf), and (c) the waters over which it asserts some degree of non-exclusive “historic rights.” While parts of this formula are intentionally ambiguous, it is clear at least that Beijing conceives of its territorial and maritime claims within the nine-dash line as separate—the former constituting an expression of unbounded sovereignty and, the latter, a claim to rights and jurisdiction premised on UNCLOS and pre-UNCLOS custom.

While China asserts that its sovereignty and rights in the South China Sea date back to “ancient times,” the first linear representation of this claim appeared in the 1930s in response to the unilateral annexation of the Spratly Islands by French Indochina. This was crystallized in 1947 when the then-Republican government of China published an official map of its South China Sea claims featuring a U-shaped line with eleven dashes. The number of dashes was reduced to nine in 1952 by the People’s Republic of China following a negotiation with Vietnam over the Gulf of Tonkin. Since then, Beijing has maintained the nine-dash line as the visual perimeter of its varied claims in the South China Sea. While the line has been often-criticized by other South China Sea claimant states (Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam) and international bodies like the Arbitral Tribunal in the 2016 Philippines v. China case, it remains a symbol and hallmark of China’s enduring interests in the region.

Given its imposing nature and the ambiguity of its implications, the nine-dash line has a habit of generating controversy when used in international contexts. The line is standard as an inset on official maps for Chinese consumption as a way of marking out the South China Sea issue in the national consciousness, but it rarely appears in non-Chinese maps of the sea outside of comparative or educational contexts. This is done so as to avoid siding with China politically in the myriad and multifaceted disputes throughout the region. Exceptions to this can be found in pop culture where stipulations to access the Chinese market often take precedence over political neutrality.

A typical example of this was found in last year’s globe-trotting adventure movie Uncharted which was banned in Vietnam and the Philippines for briefly showing a map of Southeast Asia which lent credence to China’s claims by including the nine-dash line. More recently, the newly-released blockbuster Barbie was also banned by Vietnamese censors for allegedly displaying the nine-dash line. The Philippines has allowed the movie to be screened, albeit with the problematic map blurred. The Warner Brothers studio, however, hit back at its zealous detractors saying that the dotted-line in question was a “child-like crayon drawing…that was not intended to make any type of statement.”

An upcoming concert tour in Hanoi by the Korean pop group Blackpink has also provoked the ire of nationalist Vietnamese netizens after the group’s Chinese concert promoter iMe depicted the nine-dash line on its website. Given that the disputes in question have significant symbolic and nationalist dimensions to them, it is not surprising when they play out most saliently in the public square where emotions run rampant rather than behind closed doors in well-informed discussions.

In spite of recent flare-ups, there are some glimmers of hope on the horizon that discourse over the nine-dash line could be moving in a positive, practical direction. On July 13, officials from China and the Association of Southeast Asian States (ASEAN) agreed to try and finalize negotiations on a Code of Conduct (COC) for the South China Sea by fall of 2026. Since a non-binding declaration in 2002, stakeholders among the various South China Sea claimant states have hoped for a COC to prevent provocation, mitigate escalation, and clear the ground for compromise and cooperation. However, negotiations between Beijing and the ten-nation bloc have been mired over the years by episodes of tension (such as the 2012 Scarborough Shoal standoff and the 2016 ruling in the Philippines v. China case) as well as practical matters like the COVID-19 pandemic and ASEAN’s mercurial rotating chairmanship.

Momentum shifted this year in the wake of China’s 20th Party Congress and Indonesia’s assumption of the rotating chairmanship. A China-ASEAN working group on the COC was announced this February and swiftly held an inaugural meeting in March. Now, six months later, China and ASEAN have committed to a three-year timeline on concluding the COC negotiations and have reportedly drafted an unpublished set of negotiating guidelines. Some concrete proposals have also been mentioned such as the establishment of a hotline to deescalate tensions in the event of accidental collisions, military exercises, and standoffs in the South China Sea.

The nine-dash line could continue to present a roadblock to a substantive agreement. While the ASEAN claimant states all publicly back the 2016 arbitration, which rejected the nine-dash line as delineating a zone of Chinese “historic rights,” Beijing continues in its non-recognition of the ruling seven years on. Baked into the preliminary text is also a stipulation from Beijing that claimant states must eschew cooperation with foreign energy companies in “disputed waters” which, given the expansiveness of the nine-dash line, includes significant portions of other claimant states’ entitled exclusive economic zones under UNCLOS.

Given Beijing’s enthusiasm in promoting the nine-dash line in public, it is questionable whether it would make concessions behind closed doors for the sake of reaching a legally-binding COC. However, the negotiators have ample time to pore over the line’s implications before the 2026 deadline. As is clear from even this cursory discussion, China’s claims to island features, maritime zones, and historic rights which lie within the nine-dash line are all distinct, and the specific extent of the latter two categories have yet to be completely determined. Over the course of the COC negotiations, it is possible that these claims will be clarified in private by China in order to reach an agreement on proper conduct in disputed zones. Onlookers ought to pay close attention to news stemming from these talks as it could shed greater light on the implications of the nine-dash line and the vying prospects of cooperation and confrontation in the South China Sea moving forward.

This Spotlight was originally released with Volume 2, Issue 7 of the ICAS MAP Handbill, published on July 25, 2023.

This issue’s Spotlight was written by Alec Caruana, ICAS Part-Time Research Assistant.

Maritime Affairs Program Spotlights are a short-form written background and analysis of a specific issue related to maritime affairs, which changes with each issue. The goal of the Spotlight is to help our readers quickly and accurately understand the basic background of a vital topic in maritime affairs and how that topic relates to ongoing developments today.

There is a new Spotlight released with each issue of the ICAS Maritime Affairs Program (MAP) Handbill – a regular newsletter released the last Tuesday of every month that highlights the major news stories, research products, analyses, and events occurring in or with regard to the global maritime domain during the past month.

ICAS Maritime Affairs Handbill (online ISSN 2837-3901, print ISSN 2837-3871) is published the last Tuesday of the month throughout the year at 1919 M St NW, Suite 310, Washington, DC 20036.

The online version of ICAS Maritime Affairs Handbill can be found at chinaus-icas.org/icas-maritime-affairs-program/map-handbill/.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2024 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.