The ocean covers more than 70% of the Earth’s surface and directly affects the earth’s climate, environment, and various ecosystems. Ocean temperature, a term used to refer to both the temperature of the ocean at any depth as well as the temperature of the ocean deep under the surface, plays an integral role in influencing these effects. Under natural conditions, ocean temperature is determined by the amount of heat it absorbs from solar energy, and it receives much more solar energy at the Equator than at the Poles. This difference in water temperature at various ocean depths generates currents that travel thousands of kilometers, ultimately providing favorable conditions for the reproduction of marine life and the stability of coastal ecology.

While stable and balanced ocean temperatures positively contribute to widely concerned issues (i.e., marine life security, global weather patterns and climate dynamics, and climate change), scientific observations and technical data have highlighted a concerning trend: ocean temperature is rising rapidly year by year with no sign of slowing down. In the short term, ocean temperature has a direct influence on weather phenomena such as hurricanes, cyclones, and El Niño/La Niña events. In the longer term, the rise in ocean temperatures—driven at least in part by human-induced climate change—will lead to coral bleaching, marine habitats destruction, the alteration of ocean currents, and a harsher rise in sea level, with far-reaching consequences for biodiversity, coastal communities, and global climate security.

Natural factors such as volcanic activity and solar variability can also have a short-term influence on ocean temperature. However, the consistent and rapid increase in ocean temperatures observed over the past century is primarily attributed to human-induced climate change which is mostly caused by greenhouse gas emissions such as carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4). In short, greenhouse gasses trap heat from the sun within the Earth’s atmosphere and lead to an overall warming of the Earth’s surface; more than 70% of which is the ocean. As a critical regulator of the Earth’s temperature, the ocean has absorbed a substantial portion of the excess heat from the increased greenhouse effect.

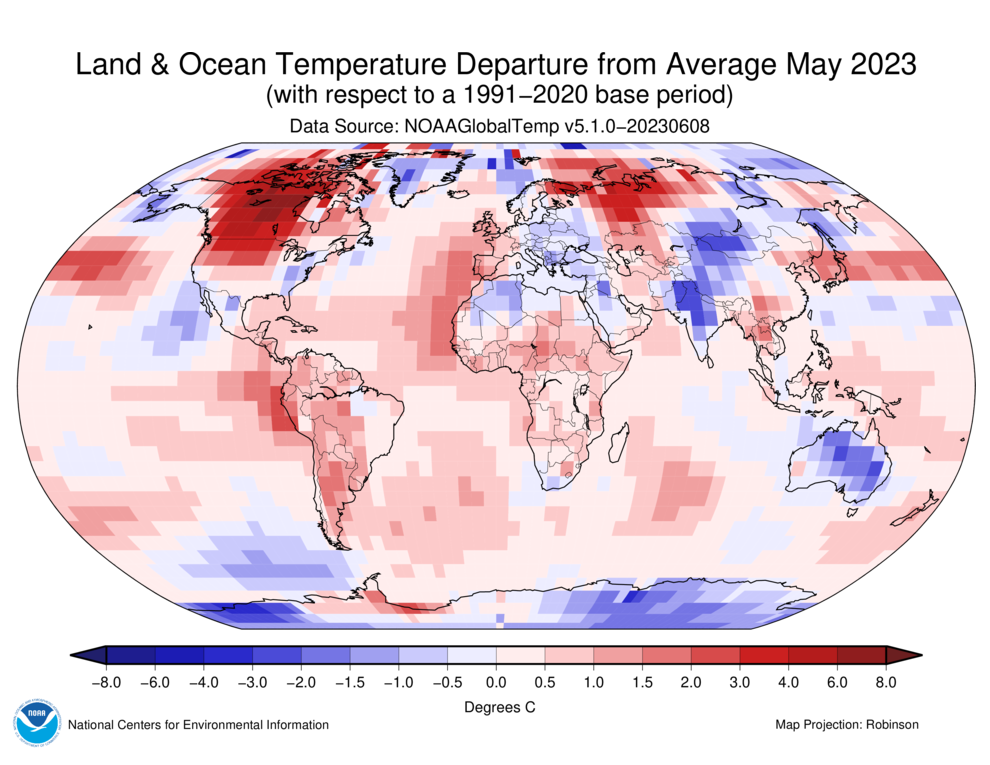

In recent years, there have occasionally been reports of ocean temperatures hitting ‘record highs’, though these reports have become even more commonplace over the last year. Scientists just announced at the beginning of 2023 that the ocean temperature in 2022 was the highest in history, though this record was broken again in less than half a year later. The unusually high temperatures started in April and have continued to exceed their normal rates. After breaking the ocean’s previous high of 21°C (69.8°F) set in 2016 in April, preliminary data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration shows that the average sea surface temperature in August reached 21.1°C (69.98°F). Although 21.1°C does not sound very high to the human ear, considering hot summers which have air temperatures that frequently exceed 40°C (104°F) in many countries, this temperature is excessively high for the ocean and all of its inhabitants. It means that, in some waters, the temperature has far exceeded its typical range and reached levels that are dangerously high in many ways.

People are already being forced to live with the consequences of rising ocean temperatures. For example, the average sea temperature of Japan reached 30°C in July, significantly contributing to the occurrence of record rainfall and the ensuing deadly flooding. Moreover, warm water and moist air not only help to generate stronger rains but also inject more power into severe tropical storms. The formation of hurricanes (known as typhoons in the Northwest Pacific) requires the evaporation of warm seawater, to start, followed by the interaction between warm air and warm seawater to give it strength. In early August, Typhoon Doksuri brought unprecedented heavy rain in China and the Philippines, causing dozens of casualties, leaving tens of thousands homeless, and destroying countless buildings. Just a few days later, another typhoon named Khanun hit Japan and the Korean peninsula, also causing casualties and heavy property damage, as Hurricane Hilary soon after battered Mexico and Southern California, marking the first time a tropical storm had landed in the region in 84 years.

Aside from weather formations, El Niño—one of two climate patterns of the Pacific Ocean that can affect weather worldwide—has returned for the first time in four years in early June. Although scientists find no direction between human-caused global warming and the formation of El Niño, scientists suggest that a warmer ocean probably fueled the arrival of El Niño. Scientists also say that the El Niño phenomenon will trigger a series of extreme weather events and will create a vicious circle by further exacerbating global warming.

According to the World Meteorological Organization, the ocean is storing more than 90% of the extra heat trapped to the Earth by humanity’s carbon emissions and only allows about 2.3% carbon emissions to warm the atmosphere. On the one hand, this shows that the ocean is of great significance for mitigating global warming. On the other hand, it also means that the ocean is already severely damaged by global warming. The extreme weather and El Niño mentioned above are only some of the events that affect people directly. In fact, rising ocean temperatures are also wreaking havoc in areas that normally receive little attention.

Coral reefs are one of the most affected organisms by rising ocean temperature. Vital hubs of biodiversity, underwater coral reefs foster intricate ecosystems that support countless marine species. Official research has long detailed how rising ocean temperatures in particular will negatively impact coral reefs. Elevated ocean temperatures can lead to coral bleaching; a phenomenon where corals expel the symbiotic algae that provide them with essential nutrients and vibrant colors. Meanwhile, warmer oceans can affect corals’ immune systems by “stressing” them, and higher temperatures also increase the reproduction of pathogens such as fungi and bacteria that can cause coral disease. As of mid-August, more than ten Caribbean and Eastern Tropical Pacific countries and regions—including the United States, Puerto Rico, Mexico (both sides of the Yucatan), and Panama—are reporting severe coral bleaching along their coasts as locals battle to combat sudden spikes in ocean temperature. Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, still recovering from massive bleaching in 2022, is also being carefully monitored due to the emerging El Niño pattern.

Besides coral reefs, there are more species of marine plants and animals that rely on specific temperature ranges to thrive. A healthy ocean temperature will help to ensure the survival of various species and maintain the vitality of the ocean. While this article primarily addresses the ecological impacts of increasing ocean temperatures, stable ocean conditions contribute to bolstering tourism and fisheries as well, with some observers fearing changes in fish populations and migration patterns. Consequently, economic factors also underscore the importance of monitoring and stabilizing ocean temperatures.

Lastly, it is also important to notice that a warming ocean can trigger feedback loops that amplify the process. For example, certain types of phytoplankton will die due to ocean temperature rise, but they play a crucial role in absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Their reduction will contribute to greenhouse gas emissions which, in turn, accelerates ocean warming. This interconnected cycle that builds upon itself suggests that it is necessary to not only slow down the acceleration of rising ocean temperature but also actively work to reverse the current problems.

This Spotlight was originally released with Volume 2, Issue 8 of the ICAS MAP Handbill, published on August 28, 2023.

This issue’s Spotlight was written by Zhangchen Wang, ICAS Blue Carbon & Climate Change Program Assistant Intern.

Maritime Affairs Program Spotlights are a short-form written background and analysis of a specific issue related to maritime affairs, which changes with each issue. The goal of the Spotlight is to help our readers quickly and accurately understand the basic background of a vital topic in maritime affairs and how that topic relates to ongoing developments today.

There is a new Spotlight released with each issue of the ICAS Maritime Affairs Program (MAP) Handbill – a regular newsletter released the last Tuesday of every month that highlights the major news stories, research products, analyses, and events occurring in or with regard to the global maritime domain during the past month.

ICAS Maritime Affairs Handbill (online ISSN 2837-3901, print ISSN 2837-3871) is published the last Tuesday of the month throughout the year at 1919 M St NW, Suite 310, Washington, DC 20036.

The online version of ICAS Maritime Affairs Handbill can be found at chinaus-icas.org/icas-maritime-affairs-program/map-handbill/.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2025 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.