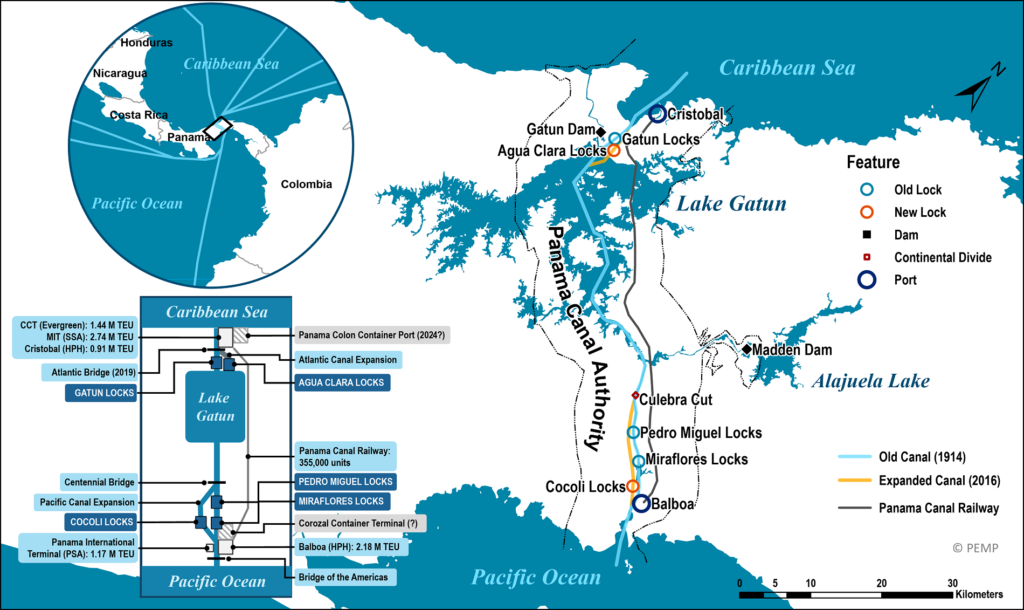

The Panama Canal is a 77 km man-made waterway, completed in 1914, that cuts through the Isthmus of Panama and allows ships from around the world to drastically reduce travel time between the Pacific Ocean and the Atlantic Ocean. Functionally, the Panama Canal operates through a system of locks with two lanes that function as ‘water elevators’ to raise ships from sea level to the level of Gatun Lake (26 meters above sea level) to allow the crossing though the Continental Divide, at which point ships are lowered through another set of locks to sea level on the other side of the Isthmus. The water used in the ‘elevator’ is transported through gravity from Gatun Lake “through a main culvert system that extends under the locks chamber from the sidewalls and the center wall.” Often called one of the Wonders of the Modern World due to being “one of the biggest and most difficult engineering projects of the modern times,” the Panama Canal has seen more than a million ships pass through since 1914—with the millionth ship passing in September 2010—and has become an invaluable feature in the global maritime shipping industry.

Debates about creating an artificial canal through the Isthmus of Panama have existed since the 16th century, with global maritime powers like Spain, the United Kingdom and France each pursuing construction of the strategically placed waterway. However, the route was not completed and made passable in full until the early 20th Century, spurred on by the Second Industrial Revolution, the simultaneous global expansion in maritime shipping and the Republic of Panama’s need to solidify its fragile independence.

On November 18, 1903, 15 years after France abandoned their construction efforts and barely two weeks after Panama declared its independence from Columbia, Panama’s ambassador to the U.S. Philippe Bunau-Varilla signed the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty with then-U.S. Secretary of State John M. Hay. This Treaty, signed during the midst of regional turmoil and change, granted the U.S. with a 10-mile wide strip of land for the canal in return for a one-time $10 million payment to Panama, an annual annuity of $250,000 and continued guarantee of Panama’s independence. Although initially celebrated as a diplomatic and engineering success, the signing of this treaty and the subsequent construction of the canal later saw much controversy over both the context of its signing and legal interpretations. In short, these controversies led to riots and legal modifications of the agreement in 1936, 1955, and 1977 when a new, two-part treaty was signed by U.S. President Jimmy Carter and Panamanian leader Brig. Gen. Omar Torrijos Herrera: the Permanent Neutrality Treaty, which declared the canal neutral and open to vessels of all nations, and the Panama Canal Treaty, which detailed the joint U.S.-Panama control of the canal until December 31, 1999 when the U.S. would fully transfer control of the Panama Canal to the Panama Canal Authority (Autoridad del Canal de Panamá or ACP), an government agency of the Republic of Panama.

Met with the undeniable, growing demand in maritime trade, the Panama Canal Authority (ACP) submitted a plan in April 2006 to expand the Panama Canal with a third set of locks; a program that began in 2007 and took nine years to complete. The ‘Third Set of Locks Project’ also raised the maximum operating water level of Gatun Lake and widened and deepened the existing channels to not only accommodate the expanding size of many cargo ships but also, in some cases, accommodate multiple ships at once. To date, with few-to-no nearby alternatives linking the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, the Panama Canal remains a heavily depended-upon maritime route for commercial vessels.

In spite of how important of a route the Panama Canal may be to the world, its operations have steadily been deteriorating in regularity due to increases in global shipping traffic and climactic droughts simultaneously pressuring the Canal’s locks system. Since July 30, the Panama Canal Authority was forced again to act to conserve the region’s water, thus reducing the number of vessels that could travel through the canal each day to 32 and leading to a backup of dozens of ships on both sides of the waterway. The average wait time for August 2023 was almost four times what it was in June 2023 and, while this average wait time reduced slightly in September, it has situated itself to levels well above historic average and is expected to remain so for a while.

What this means is that ships are competing for spots in line—a line that has peaked at 160 spots at one point in August rather than the typical 36—amidst congestion that some estimate could last until 2024. One ship in the Panama Canal recently paid $2.4 million at an auction to skip past the logjam of vessels; a price that did not include the normal canal-crossing fee which can range between $150,000 to over $1 million by itself.

Local authorities and regulators continue to actively monitor and report on the situation, subsequently making adjustments to its reservation system and allowances as necessary. Aside from restricting the number of daily passages, another such limitation is changing the maximum vessel draft allowance to 44 feet—a reduction of 6 feet from the typical allowance—which inevitably changes the size and the tonnage, potentially, of passable vessels. The Panama Canal has experienced low levels before (in 2016 and 2019) but neither observers nor authorities are now expecting to be able to lift restrictions on vessel traffic in 2023. During the first week of September, the Panama Canal Authority officially confirmed prior estimates on the issue, saying that the limits on daily transit and vessel draft will remain unchanged for the rest of 2023 and throughout 2024 due to insufficient rainfall. Some observers are now wondering if the Panama Canal Authority is preparing to advance yet another new round of restrictions. These unexpected limitations to Panama Canal passage—driven at their roots by soaring worldwide temperatures—are leaving global supply chains, already trying to recover from more than three years of pandemic and preparing for a major holiday season, under stress yet again.

There are several select warnings that these events bring to mind. First, there is the oncoming wariness of corporate monopolization. If gone unchecked, such a situation could lead to market monopolization by or favoritism for the largest companies who are more easily able and willing to pay higher crossing fees; as evidenced by the successfully played $2.4 million auction payment to skip the cuing line of the Canal. Second, there is the stark realization of the value of diversification in global maritime shipping routes—and how this lack of diversification is a vulnerability. For the first time in over a century, the world may need to actively look for alternative shortcuts to connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, even if such a search comes up empty. Third, there is the reminder of global supply chains functionality and its fragility. One major change in the system is leading to global implications across a variety of industries, all of which depend on successfully delivering goods to customers in a timely manner. The world was already reminded of this fragility during the Covid-19 pandemic and is now facing compounding problems.

However, of all of these reminders, the most marked is the inevitable connection between global warming and the stability of not only maritime shipping but the global maritime economy at large. Lake Gatun, the primary source of water that allows vessels to cross the Continental Divide, has been experiencing a drought for the last 20 years, and the Canal Authority themselves identify the root cause of the issue to be the ongoing drought: “To ensure the canal remains open to the world of commerce, the Panama Canal Authority has implemented strategic measures over the past several months…to mitigate the impacts from climate change and a subsequent dry season.” Furthermore, with more ships lining up at the gate, the more fuel is being burned and released into the atmosphere, thus further contributing to global warming. It is understandable why many observers are frustrated and calling for systematic change across several parts of the shipping industry.

Pulling back for a moment from addressing technical supply chain concerns, it is important to note that the Panama Canal itself remains a successful symbol of diplomacy and human determination. On September 7, 2023, Panama Ambassador Francisco O. Mora gave remarks celebrating the 46th anniversary of the signing of the 1977 Carter-Torrijos Treaty: “In closing, the Panama Canal stands as a symbol of human achievement and strong bilateral cooperation between the United States and Panama. It beckons us to recognize the power of diverse contributions, the urgency of environmental protection, and the strength of Inter-American collaboration.” As today’s world is forced to operate in the midst of modern troubles, it is not only proper but essential to appreciate and learn from our past—especially when that past, which the world did successfully navigate through, was itself once riddled with dissent and signs of inevitable failure. To simply ‘copy and paste’ from the past would not be effective, as the ‘battles’ are different, but there is also no need to start from scratch in favor of looking for already-proven insight—that would be a detrimental waste of emotions and resources in navigating through our own modern contentions.

This Spotlight was originally released with Volume 2, Issue 9 of the ICAS MAP Handbill, published on September 26, 2023.

This issue’s Spotlight was written by Jessica Martin, ICAS Research Associate & Chief Editor, ICAS Newsletters.

Maritime Affairs Program Spotlights are a short-form written background and analysis of a specific issue related to maritime affairs, which changes with each issue. The goal of the Spotlight is to help our readers quickly and accurately understand the basic background of a vital topic in maritime affairs and how that topic relates to ongoing developments today.

There is a new Spotlight released with each issue of the ICAS Maritime Affairs Program (MAP) Handbill – a regular newsletter released the last Tuesday of every month that highlights the major news stories, research products, analyses, and events occurring in or with regard to the global maritime domain during the past month.

ICAS Maritime Affairs Handbill (online ISSN 2837-3901, print ISSN 2837-3871) is published the last Tuesday of the month throughout the year at 1919 M St NW, Suite 310, Washington, DC 20036.

The online version of ICAS Maritime Affairs Handbill can be found at chinaus-icas.org/icas-maritime-affairs-program/map-handbill/.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2025 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.