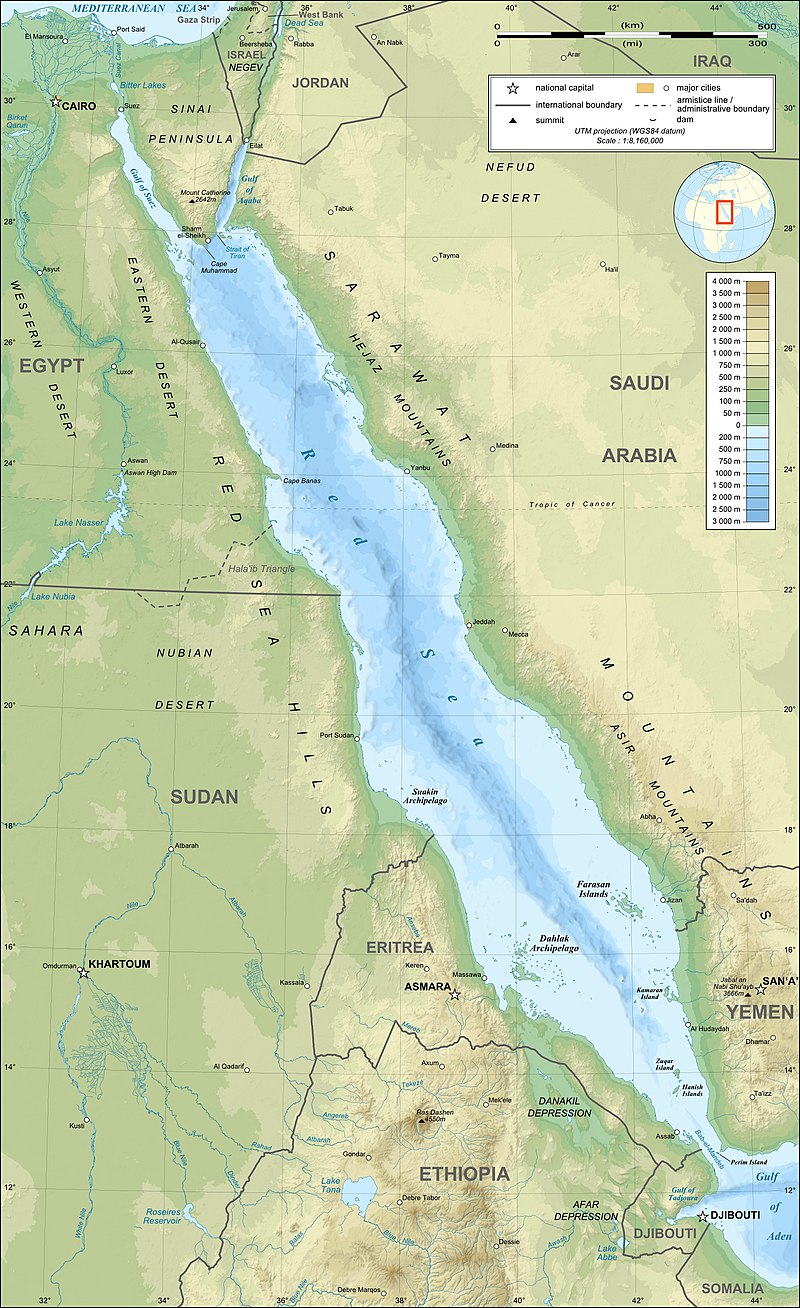

The Red Sea is a seawater inlet of the Indian Ocean, roughly 1,200 miles long and 190 miles wide at its widest point, that separates the African and Asian continents and connects the Mediterranean Sea with the Arabian Sea. It is connected to the Indian Ocean and Asia via the Bab-el-Mandeb strait and the Gulf of Aden at its south, and to the Mediterranean Sea and Europe via the Gulf of Suez and the Suez Canal at its north. To the majority of its east lies Saudi Arabia, with Yemen bordering its southeasternmost extent, while Egypt, Sudan, Eritrea, and Djibouti lie to its west and Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula caps its northern extent. Because of its narrow width, there is no portion of the Red Sea that does not lie in one of the exclusive economic zones of its six coastal nations.

Geologically, it is part of the Red Sea Rift which itself is part of the Great Rift Valley; the most well-known rift valley on Earth. Scientific research believes the Red Sea to have originated from the Indian Ocean flooding the rift valley millions of years ago upon the Arabian African tectonic plates drifting apart, and expects it to eventually continue to drift apart and separate Africa and Asia entirely. This body of water, one of the first large bodies of water mentioned in recorded history, also has extensive cultural and historical significance as it has been being used and accessed by empires, cultures, religions, and explorers for over 4,500 years.

Like the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea is one of the most saline bodies of water in the world largely due to high evaporation rates and insignificant freshwater inflow, with its salinity typically recorded at 40-41 parts per thousands (ppt) but capable of reaching 50 ppt in certain areas. This measure is compared to the typical range of sea water salinity at 33-37 ppt. While the Red Sea does reach depths of 3,000 meters at its deepest point, it is holistically shallow, with one-quarter of the Red Sea being less than 50 meters deep. As the Red Sea simultaneously contains some of the world’s hottest water from two distinct monsoon seasons thus making it the world’s most northern tropical sea, it is the habitat of over 1,200 fish species and 200 soft and hard corals. These unique characteristics and the extensive presence of marine life and corals led the World Wide Fund for Nature to identify the Red Sea as a “Global 200” ecoregion and a priority for conservation.

Still, because of its geographical location, the Red Sea has been used as a vital maritime shipping route since ancient times. According to the U.S. Naval Institute, about 12% of global maritime trade transits the Suez Canal and the Red Sea. Without this route, ships traveling between the Indian Ocean and Europe have to sail around the southern tip of Africa, extending their journey by at least 10 days, or by about 30%. There are also several types of mineral resources found in the Red Sea region—including petroleum deposits, evaporite deposits (magnesite, gypsum, etc.), sulfur, phosphates, and heavy-metal deposits—that have caught the attention of governments and private entities.

It is largely because of this strategic importance to global maritime shipping that the Red Sea is often targeted by adversaries, such as the Yemen-based Houthi rebel group who have been attacking commercial ships transiting the Red Sea for over 10 weeks. Since October 17, 2023, exactly one week after the Houthi leader warned against U.S. interference in the Gaza conflict, the Iranian-backed Houthi rebels have been targeting ships that they say have a connection to Israel as a sign of solidarity with the Gaza-based Hamas group currently fighting against Israel in the Gaza strip. As warned, these attacks have typically come in the form of ballistic missiles fired from and aerial drones originating from Houthi-controlled regions of Yemen, and in October and November were also shot towards Israel itself.

As December approached, these attacks began primarily targeting private, commercial vessels in the Red Sea, most of which occurring as they transit through the Bab-el-Mandeb at the southern exit of the Red Sea, which Yemen borders. These attacks appeared to only increase in frequency over December. For example, on December 3 USS Carney responded to three separate distress calls from Bahamian-flagged, Panama-flagged, and Panamanian-flagged vessels while patrolling the Red Sea. The Norwegian Motor Tanker Strinda was attacked while passing through the Bab-el-Mandeb on December 11; the same day that French guided-missile frigate FS Languedoc (653) shot down a third drone with surface to air missiles while patrolling nearby after it was reportedly under attack two days prior. Three days later, Houthis attempted to board and reroute the Hong Kong-flagged Maersk Gibraltar cargo container ship after firing a ballistic missile at it; an attack that was deflected by the USS Mason (DDG-87). The following day, two Liberian-flagged ships were attacked and caught fire as a third was hailed by the Houthi told to turn to Yemen, which the crew did not do. Three days after that, two other missile attacks were separately reported against a Cayman Islands-flagged chemical/oil tanker and a Liberian-flagged bulk cargo ship. The Houthis have also seized and raided ships since mid-November—such as the Japanese-operated, British-owned vehicle carrier Galaxy Leader—prompting the U.S. to call their actions “piracy” and potentially designate the Houthi as a “terrorist” group.

These attacks, along with others of similar nature, prompted reactions from both the private and public sectors. The United Kingdom Maritime Trade Operations, like other organizations of its kind, continued to report a series of warnings over the last 6 weeks regarding this region, the comparative amount of which emphasizes the severity and rarity of such activities. Some companies (A.P. Moller – Maersk, COSCO, BP, Equinor, CMA CGM, Mediterranean Shipping, Evergreen Marine, etc.) officially halted all tanker transits through the Red Sea, forcing vessels to reroute around the southern tip of Africa in spite of the soaring prices and major supply chain disruptions caused by skipping the Red Sea and additional 10 days of sailing. Notably, there are still ships successfully transiting the route. Still, from November 19-December 19, the Suez Canal Authority recorded 2,128 ships had traveled through the route while 55 ships diverted via the Cape of Good Hope.

On December 18, one week after the White House called allies to fill the “natural response” of expanding a multinational naval task force to secure the region, the U.S. Department of Defense established a new multinational security initiative named Operation Prosperity Guardian to protect commercial traffic and ensure freedom of navigation in the Red Sea. Supported by Combined Task Force 153, Bahrain, Canada, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Seychelles, Spain, and the United Kingdom were named as initial allies in the Operation. That number reportedly expanded to 20 nations, though there appears to be reluctance in nations aligning themselves with the Operation as reports are now coming of France, Italy and Spain snubbing the Operation.

Meanwhile, the Houthi rebels released vows that the attacks against Israeli-linked vessels would continue until Israel stops the conflict in Gaza, and they have kept that vow so far. Furthermore, the regional expanse of their attacks may be widening. On December 26, drone attacks were launched from Iran against two Indian merchant vessels less than 200 nautical miles off the coast of India, though the responsible party who New Delhi has promised retribution against has yet to be identified. On the same day, U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) forces worked to intercede 12 attack drones, three anti-ship ballistic missiles and two land-attack cruise missiles that were fired on the same day by Houthi forces from Yemen.

In spite of these continued attacks, the establishment of Operation Prosperity Guardian has given some companies such as Maersk the confidence to safely utilize the Red Sea route once again, with several of their ships returning to the typical route on December 27. The stabilization of the oil market also may be an indicator of softening tensions in the area, but many container companies still consider the Red Sea route as too dangerous.

The ongoing situation of Houthi rebel attacks in the Red Sea is a live case study in the fragility of global maritime supply chains. Similar to March 2021 in the Suez Canal or just this last summer in the Panama Canal, the world is witnessing the downfalls of inflexible maritime supply chains. It is prompting a deeper exploration into solution-building and establishing variety. Given how similar problems appear to be populating, it could leave some to question whether or not the world is sufficiently learning from these instances, whatever their root cause may be.

While there is no easy answer, global maritime transportation companies must continue to value investing in options, such as cargo flights or supporting fresh innovation. Parties would also benefit from keeping the existing alternative routes such as those in Africa updated and communicative so ports do not become overwhelmed. Decentralizing supply chains seems like an attractive option at first, as this system provides more flexibility, but it is not realistically feasible to expect centuries of habit and globally integrated infrastructures to change; especially as the ever-growing pressure on the maritime shipping industry to address climate change persists.

This region is no stranger to maritime piracy. The Horn of Africa is notorious for being one of the most highly pirated maritime regions in the world, and other attacks such as hijackings are still ongoing. However, one special element of these attacks is the publicity and regular communication that the Houthi is employing to garner and retain global attention. Their filming of the November 19 overtaking of the Galaxy Leader merchant vessel was an intense message to the world and a warning that any other Israeli-linked vessel could be attacked in the same way. One way or the other, their communication efforts have driven many Israeli-linked ships to reroute while distracting governments. It is too soon to tell whether or not how effective this tactic will remain.

Last, while Operation Prosperity Guardian is still fledgling, its initial setup shows how establishing joint military operations is more difficult than it may seem, even among allies and with a clear adversary in sight. U.S. Secretary Lloyd Austin called it “an international challenge that demands collective action” but, even if his counterparts agree, there is an endless list of considerations and several unknowns. Perhaps some of these U.S. allies are looking at how unexpectedly long the Ukraine-Russia conflict has lasted and fear a similar case taking place in the Red Sea. One analyst described the task force as a “half measure that the Houthis will test.” Given how the Houthi leadership has also been vocalizing their warnings and doing what they have said they would, it would be wise to fear testing their resolve and foolish to disregard their words as pure propaganda, so their caution to tie themselves to an official military operation is understandable even if contributing seems like the clear answer.

This Spotlight was originally released with Volume 2, Issue 12 of the ICAS MAP Handbill, published on December 28, 2023.

This issue’s Spotlight was written by Jessica Martin, ICAS Research Associate & Chief Editor, ICAS Newsletters.

Maritime Affairs Program Spotlights are a short-form written background and analysis of a specific issue related to maritime affairs, which changes with each issue. The goal of the Spotlight is to help our readers quickly and accurately understand the basic background of a vital topic in maritime affairs and how that topic relates to ongoing developments today.

There is a new Spotlight released with each issue of the ICAS Maritime Affairs Program (MAP) Handbill – a regular newsletter released the last Tuesday of every month that highlights the major news stories, research products, analyses, and events occurring in or with regard to the global maritime domain during the past month.

ICAS Maritime Affairs Handbill (online ISSN 2837-3901, print ISSN 2837-3871) is published the last Tuesday of the month throughout the year at 1919 M St NW, Suite 310, Washington, DC 20036.

The online version of ICAS Maritime Affairs Handbill can be found at chinaus-icas.org/icas-maritime-affairs-program/map-handbill/.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2025 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.