Image Source: UnSplash

Research Associate & Program Coordinator

China is the third largest nuclear weapons state in the world and has built up an arsenal of 270 nuclear weapons since its first nuclear test in 1964.

China maintains a policy of no first use. Under these guidelines nuclear weapons cannot be used offensively, and can only be fired in retaliation for a nuclear attack.

Unlike the United States and Russia, China does not keep its nuclear weapons on hair trigger alert and stores its nuclear warheads separately from their delivery vehicles. This enhances crisis stability by ensuring the weapons cannot be launched mistakenly in response to a false alarm.

China operates a dyad of nuclear delivery vehicles. This includes a variety of land-based missiles, such as intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM) and four Jin-Class submarines

China is not known to operate bombers or cruise missiles in support of its nuclear mission. However, evidence has emerged that China is developing an air-launched cruise missiles which may be capable of delivering both conventional and nuclear warheads.

The United States and Russia are both adding new capabilities to their nuclear arsenals. If China perceives its potential adversaries as gaining a qualitative advantage, Beijing will almost certainly follow suit. These developments run a very real risk of igniting a new arms race.

Earlier this year the Trump administration unveiled the 2018 nuclear policy review. Unsurprisingly, the document was a significant departure from anything produced by Trump’s predecessors. Every American president since Richard Nixon has cut the role and number of nuclear weapons in U.S. national security strategy. Trump however, reversed that trend, calling for new low-yield nuclear weapons to be added to the U.S. arsenal and expanded the circumstances under which they can be used.

Russia appears to be embarking on a similar path. During his address to the Russian Duma last month, President Vladimir Putin announced that his country had successfully tested a compact nuclear propulsion engine that would allow nuclear armed cruise missiles and underwater drones to travel virtually unlimited distances. Putin touted these new weapons as being able to penetrate any defense system in the world. This is bad news for everyone, including Russia.

Nuclear deterrence is an all or nothing game that boils down to being able to inflict unacceptable losses on an adversary. It does not take many nuclear weapons to accomplish this goal, nor is there any credible reason to believe that adding low-yield nuclear weapons to the mix will make the unthinkable any less likely. On the contrary, by introducing new weapons that are tailored for nuclear war fighting, Russia and the United States are increasing the likelihood of having to fight they are seeking to avoid.

This is a principle that China has demonstrated a clear understanding of ever since entering the nuclear weapons club.

In 1964 China tested its first nuclear bomb, taking the whole world by surprise. It was no secret that China had been working on a nuclear weapons program, but the pace at which China managed to race across the finish line caught everyone of guard, especially the United States. U.S. intelligence consistently underestimated China’s progression towards the bomb, and when China finally demonstrated its newfound capability to the world, the U.S. response was somber.

President Lyndon B. Johnson painted an eerily similar picture to the current American reaction to North Korea’s ICBM tests. It was a narrative of a rogue communist dictatorship, led by a madman who slaughtered his people and had poured all of his resources into developing “a crude nuclear device.” Most U.S. analysts concluded that Mao wasn’t a rational actor making China an undeterrable foe. At one point nuclear strikes were considered as a viable option for halting China’s nuclear program in its tracks. Ultimately, that plan was was abandoned.

54 years later it is stunning to see how wrong these observers were in their predictions.

Despite the irrationality of the cultural revolution, Mao Zedong understood that nuclear weapons could never be used. He is often quoted as referring to nuclear weapons as ‘paper tigers,’ terrifying illusions that have no power. To this day, China’s nuclear weapons policy largely reflects Mao’s philosophy.

In the decades since China conducted its nuclear weapons test, it has accumulated an arsenal of roughly 270 nuclear warheads. Forperspective, less than 20 years after becoming nuclear weapons states both the United States and Russia had stockpiled more than 30,000 nuclear weapons. None of China’s nuclear weapons can be considered low-yield, a vague definition that generally refers to weapons with an explosive force that is less than 150 kt (10 times more powerful than the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima). There is a bizarre logic at play here. By forgoing low-yield nuclear weapons and relying on high-yield nuclear weapons, China is strengthening its paper tigers. By making them appear more ferocious, China reduces the odds that it will have to resort to nuclear weapons in the first place.

China adheres strictly to a policy of no first use. Under these guidelines, China’s nuclear arsenal can only be used for retaliation, in the event that it has already been attacked with nuclear weapons. Another significant feature of Chinese thinking on nuclear weapons is that China stores its warheads separately from its delivery vehicles. In the event of a crisis, this eliminates the risk of mistakenly firing the weapons in response to be a false alarm.

Because China’s policy does not allow for the first use of nuclear weapons in a conflict, the main focus of its arsenal is on survivability. The majority of its nuclear forces are land based missiles, permanently based in hardened silos and on road mobile delivery vehicles that can be maneuvered around the country to avoid targeting by enemy forces. The remainder of China’s nuclear deterrent is based on four Jin-class ballistic missile submarines (SSBN), capable of carrying a total of 48 submarine launched ballistic missiles. China retains an older Xia-class submarine, but it is not considered operational and is likely only used for training purposes. In the event of an extreme crisis, it could likely be called upon for limited missions. China’s nuclear submarines do not conduct regular deterrence patrols, nor do the store their nuclear warheads on board. U.S. intelligence assessments suggest that China might be building a 5th Jin-class submarine, but is unlikely to invest in additional submarines of that series. Jin-class submarines are noisier than their American or Russian counterparts, making them easy for potential adversaries to detect. China will likely hold off were on acquiring additional submarines for its nuclear force until it is able to develop an field a new class of SSBN.

Over the years, China has significantly upgraded its nuclear arsenal. Many of its outdated missiles have been replaced. But although the amount of weapons in its nuclear arsenal has gradually increased, most of these upgrades have been qualitative, not quantitative.

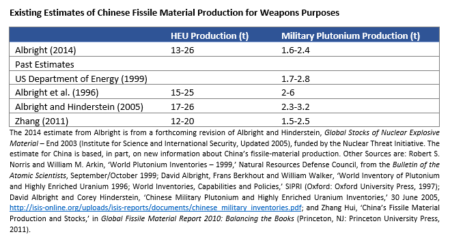

China’s ability to expand its inventory of warheads is severely limited by the amount of highly enriched uranium (HEU) and weapons grade plutonium it has on hand. In the 1980s China suspended its military enrichment programs and repurposed them for civilian nuclear energy production. China no longer has the capability to produce additional weapons grade fissile material, and its existing stockpile consists of about 14 tons of HEU and 2.9 tons of plutonium. This is roughly enough material to produce 730 additional thermonuclear weapons. Even in a worst-case breakout scenario China’s total inventory could reach about 1000 nuclear weapons, less that on sixth of Russian or American nuclear arsenal.

China has demonstrated remarkable restraint in its approach to nuclear weapons. There is no doubt that China has the resources to achieve parity with the U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenal choose to do so, but it has not. Rather than engage in an arms race, China has opted for a minimalist approach to deterrence and invested its resources in economic growth. However, there is no guarantee that this restraint will last forever.

The U.S. nuclear posture review refers to China as a hostile great power that poses a “major challenge for U.S. interests in Asia.” The review specifically states that the decision to introduce new low-yield nuclear weapons is part of a new “tailored strategy for China.” These policy shifts are provocative and destabilizing. If China perceives the United States to be gaining the upper hand and jeopardizing its nuclear deterrent, it will take moves to negate those actions. Russia’s moves will have similar consequences. Although the United States is the unnamed target of its nuclear threats, China is a potential target of Russia’s nuclear arsenal and will have serious concerns about how upgrades to Russia’s nuclear capabilities affect the survivability of its own force.

China has already responded forcefully to these developments, stating that “China must strengthen its nuclear deterrence and counter-strike capabilities to keep pace with the developing nuclear strategies of the United States and Russia.” Even before the US announced its new nuclear guidelines there were rumblings that China might be reconsidering its no first use pledge. It is also thought to be upgrading some of its nuclear missiles to be able to carry multiple warheads, and is the process of developing an air-launched cruise missile, which may be capable of carrying nuclear warheads. By targeting China, the United States has created a large incentive for Beijing to move forward with these plans.

If Russia and the United States don’t reconsider the path they have embarked upon, there is a very real possibility that their actions could trigger a new arms race. Both countries should recommit to reducing the role of nuclear weapons in their national security strategy and pursue additional cuts to their bloated nuclear arsenals. Washington and Moscow needs to take a page from Beijing’s playbook and see nuclear weapons for the paper tigers that they are.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2025 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Opinion | As China modernises its navy, the US races to stay ahead