Cover Image: “PIA23302: First Humans on Mars (Artist’s Concept),” July 2019 (NASA). This artist’s concept depicts astronauts and human habitats on Mars. NASA’s Mars 2020 rover will carry a number of technologies that could make Mars safer and easier to explore for humans.

Research Assistant

China started developing space capabilities in the 1950s alongside their nuclear missile program. It was not until China achieved moderate prosperity by the 1990s that it could act on its strategic goals in space, which China has been pursuing headlong since. Following its first manned launch in 2003 and first lunar orbit in 2007, the West began to acknowledge China’s rapid space development and the potential competition therein.

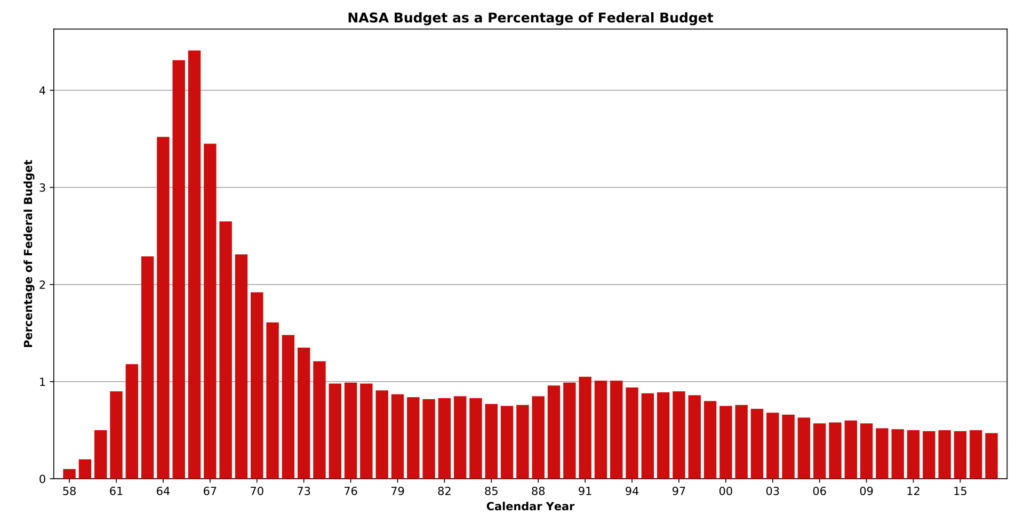

After the U.S. won the race to the Moon in 1969, NASA’s government funding rapidly dropped to an annual budget hovering around 0.5% to 1% of all U.S. government spending. Since the Second Barack Obama Administration, the United States’ space development has begun to receive elevated attention as a part of the United States’ National Security Strategy.

The Trump Administration has further expanded financial and policy support for space development and has laid out an ambitious timetable to return American astronauts to the Moon and establish a lunar presence. However, the Administration’s narrative has also nudged the U.S.’ policy narrative on space from scientific discovery towards military defense, exemplified by the creation of the U.S. Space Force and Space Command in December 2019.

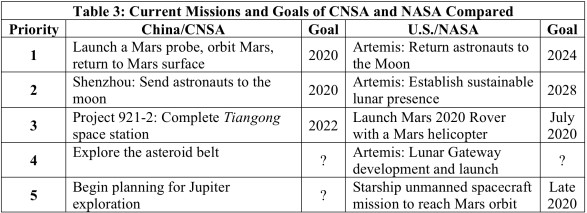

Both the CNSA and NASA have ambitious Lunar and Mars landing missions at the forefront of their space programs that could succeed at a faster rate and for less funding if cooperation was established. Space stations is also a timely point of cooperation, given that the CNSA has begun constructing China’s permanent manned space station, Tiangong, which shares overlapping interests. However, it could also end up competing with the aging International Space Station and the new NASA-led Lunar Gateway project.

Leaving China to independently develop space capabilities is detrimental to U.S. national security. Isolation leads to information loss and an inability to establish checks and balances. Furthermore, rejecting cooperation opportunities can slow U.S. scientific progress and dent the U.S. multilateralist image, which could lead to the loss of potential U.S. partners in the space domain.

There is still time to steer the narrative from competitive warfare to cooperative progress. Most notably, legislative changes should be enacted to facilitate cooperation with China in space, starting with reevaluating the outdated and isolationist 2011 Wolf Amendment. It is a mistake to consider the door closed on U.S.-China cooperation in the space domain, especially as the CNSA proves to be a dedicated competitor in the realm, both in terms of aspirations and achievements.

Traditionally, nations have acknowledged three domains in which warfare is conducted: Land, Sea, and Air. With the space race of the Cold War period and the rapid popularization of the internet, two additional domains—Space and Cyber—have been added, bringing unprecedented challenges and encouraging lofty goals. Nations have been actively contesting over space since the 1950s and as worldwide interest in the domain suddenly revived, China rapidly became a primary influencer and potential competitor in outer space. Subsequently, the United States has stepped up its commitments to maintain precedence in this crucial domain.

Described by The Guardian as the greatest “appetite for space missions” since the 1960s, present-day space exploration faces the highest chance of success if the greatest minds find common ground. The unique characteristics granted in the space domain demand a unique response based on long-term thinking and an equally-beneficial outcome—not just a win-win outcome. The United States’ space program is currently poised to shape the dialogue in the space domain and sidestepping opportunities to collaborate with Chinese counterparts could prove detrimental to U.S. national security as well as global stability at large.

This primer frames the debate on cooperation between the two national space agencies of the People’s Republic of China and the United States—the Chinese National Space Agency (CNSA) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). A general overview of their histories and goals will be provided before four incentives for U.S. cooperation with China’s space program are explored. These incentives are:

Lastly, points of cooperation will be presented and next steps in U.S. legislative changes will be proposed; namely, changes to the Wolf Amendment introduced in 2011 that has proven detrimental to U.S.-China cooperation in the space domain. Initially added as a preventative measure against technology theft by legally restricting bilateral partnerships, many experts believe that the Wolf Amendment is doing far more harm than good and should be reconsidered.

Formed in 1993, the CNSA is a civilian Chinese national agency housed under the State Administration for Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense (SASTIND, 国家国防科技工业局), and the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT, 共和国工业和信息化部). Especially since Xi Jinping’s presidential appointment in 2012, Beijing has directly linked space exploration with national pride and technological progress in public addresses and central government documents. The 1990s and 2000s witnessed China establishing multiple partnerships in space development, most notably with Russia, the European Union, Brazil, Canada and Nigeria.

While exact budget amounts for CNSA are elusive to determine due to dual-use technology applications and lack of opacity on the part of Beijing, it is evident that the space program enjoys a multi-billion USD budget that has received increasing support from decision-makers since the early 1990s.

For example, Space Daily reported in October 2006 that China’s space budget exceeded $2 billion. The following year, Jeffrey Logan of the U.S. Congressional Research Service reported Western experts estimate CNSA’s budget to be about $1.4-2.2 billion annually while the CNSA reports its spending in 2009 was equal to one-tenth of NASA’s, or around $1.7-1.8 billion. Around this time, GlobalSecurity.org calculated CNSA’s budget based on launches to instead be about $10 billion annually. Estimates by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development place CNSA’s budget in 2009 and 2013 at $6.1 billion and $10.8 billion, respectively. The Space Report Online has released 11 annual reports on “Chinese Government Space Budget” since 2008, all of which emphasize the dramatic space progress across the last two decades and that China’s space responsibilities are “shared by several agencies.” Current estimates typically set CNSA’s budget at around $8 billion. These trends heavily attest to Beijing’s dedication to space development, which Brian Wang estimated in July 2019 could reach $15-20 billion by 2030.

Aligned with its customary five-year plan cycle, Beijing has released four white papers titled “China’s Space Activities” (中国的航天) in 2000 [ENG], 2006 [ENG], 2011 [ENG], and 2016 [ENG]. These reports reiterate the purpose and principles of Chinese activities in space, major developments over the last five years, and the major tasks for the following five years. It also extensively encourages international exchange and cooperation with other nations’ space agencies and international organizations. The next white paper is expected to be released in December 2021.

NASA is a civilian U.S. federal agency and acknowledged as the preeminent leader in space exploration. With 18 research centers and launch facilities across the United States, its presence is widespread as it attracts some of the most brilliant and passionate minds from around the world. Established in 1958 at the heart of the Cold War, NASA’s vision is: “To discover and expand knowledge for the benefit of humanity.” It rapidly became the heart of American pride and prestige, culminating in winning the space race for the U.S. in 1969 by landing a human being on the Moon for the first time.

Since NASA is a U.S. government agency, detailed information on budget requests and subsequent allocations since 1958 are publicly available. For fiscal year (FY) 2020, NASA’s approved budget is US$22.629 billion, or 0.48% of all U.S. government spending. After a notable decline around 2009-2013, NASA’s budget has been steadily increasing, with this year’s budget increasing by 5.3% from the previous fiscal year. The FY 2020 President’s Budget Request projects that NASA’s budget will continue to increase through FY 2024.

In the FY 2021 President’s Budget released on February 10, 2020, President Donald Trump called for a $25.2 billion total budget for NASA for FY 2021, which would increase NASA’s funding by 12% compared to the FY 2020 enacted level. This financial boost, called by NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine “one of the strongest NASA budgets in history,” is specifically aimed at getting humans to the moon and then to Mars.

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been pursuing the space domain since it began researching ballistic missiles in the 1950s. In 1992, China formally recognized the great strategic value in having a space station, which turned the national space program’s focus from commercial satellites to manned missions. The following year, the China National Space Administration (CNSA, 中国国家航天局) was founded and has since been making clear advancements in its manned spaceflight Shenzhou program also known as “Project 921.” China first sent humans into space in 2003 and first orbited the moon in October 2007. In 2008, CNSA was already regarded by Western experts as an impressive “world leader in yearly space launches.”

As confirmed by CNSA’s vice administrator Wu Yanhua in January 2017, CNSA’s four mission goals are: launching its first Mars probe and orbital in 2020; returning to Mars’ surface for exploration and sampling; conducting an asteroid exploration; and develop a plan for exploring Jupiter. Developing lunar exploration, manned spaceflight, and “high resolution, targeted observation and survey systems” (高分辨率对地观测系统) continue to also be a major priority. China’s ultimate goal is to “rise and be ranked as a powerful nation in space travel” by around 2030.

Experts concur that CNSA is well on its way to accomplishing these goals. Its Chang’e-4 rover made history on January 2, 2019 as the first vehicle in history to land on the dark side of the moon while its lunar land rover Yutu 2 broke Russia’s longevity record two weeks before the Chang’e-4’s first anniversary. For the first time, the prestigious Royal Aeronautical Society recognized CNSA employees last December with a Team Gold Medal for their work on the Chang’e-4 mission. In the spirit of the one-year anniversary of its soft landing on the moon, on January 2, the CNSA published a catalog of scientific data collected throughout the last year. The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) China Power project in Washington, D.C. released an analysis of China’s advancing space launch capabilities concluding that, while it still needs to make significant headway with closing the technology gap, “China sits among [an] elite group of spacefaring nations.”

In October 2018 the Chinese company C-Space revealed CNSA’s “Mars Base 1” located in the depths of China’s Gobi Desert. Described as a “space station on Earth,” Mars Base 1 conducts research and training specifically for CNSA’s projected Mars missions. It reportedly cost US$373 million and is regarded as the “most advanced Mars training facility in China.”

China is already amassing the means and expertise to become a serious competitor with the U.S. in space and shows little sign of relenting. In its most recent white paper on space, published December 2016, Beijing applauded its rapid independent development and reiterated its commitment to becoming superior in the space domain. In February 2020, the Space Foundation awarded one of its two 2020 Space Achievement Awards to CNSA for its historic Chang’e-4 mission.

Past tradition places outer space exploration in a unique pocket of national security. More than gaining technical advantages, winning the ‘space race’ of the Cold War was about earning the national prestige and recognition that comes with unprecedented scientific achievements into the unknown. This spirit, while dampened by political agendas and suspected militarization of the domain, still exists and is what sets this physical warfare domain apart from the four others.

Mars missions are at the top of NASA’s priorities. The U.S. has had a notable presence orbiting Mars since 1996. NASA’s Sojourner rover first arrived on its surface in July 1997 aboard the Mars Pathfinder before NASA lost transmissions that September. NASA’s next goal is its Mars 2020 Rover, which has been in active development since 2014. The soon-to-be-named rover will replace the Opportunity rover that last sent images from Mars in June 2018. Scheduled to launch in July 2020, it is depicted as a “robotic scientist” built to investigate the planet’s suitability for human living conditions and return with samples.

On January 19, 2020, NASA and SpaceX successfully completed the “final major flight test” of their Crew Dragon spacecraft and Falcon 9 rocket, which Chief Engineer at SpaceX Elon Musk called a “picture perfect mission.” A month earlier, Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner spacecraft safely but unsuccessfully finished its Orbital Flight Test without reaching planned orbit and docking at the ISS. One of NASA’s more ambitious development projects is its Quiet SuperSonic Technology piloted aircraft (X-559 QueSST), though it is not intended for outer orbit use.

“President Donald Trump has asked NASA to accelerate our plans to return to the Moon and to land humans on the surface again by 2024. We will go with innovative new technologies and systems to explore more locations across the surface than was ever thought possible. This time, when we go to the Moon, we will stay. And then we will use what we learn on the Moon to take the next giant leap—sending astronauts to Mars.”

- Jim Bridenstine, NASA Administrator

As early as his presidential inauguration, President Donald Trump had brought the space domain back to the forefront of American national security policy. On June 30, 2017, 24 years after its disbandment, the Trump Administration revived the National Space Council to guide U.S. national space strategy and, later that year in December, signed the Space Policy Directive-1 that sets goals for human launches above low-orbit and beyond to Mars. In March 2018, the administration unveiled its America First National Space Strategy that emphasizes “peace through strength” by enhancing “deterrence and warfighting options.”

Compared to the FY2019 enacted NASA budget, the final FY2020 President’s Budget Request (PBR) for NASA depicts a steep increase in support for Exploration (+27%), Space Technology (+24%), Safety, Security & Mission Services (+12%), and Construction and Environmental Compliance (+72%) initiatives. The Mission Fact Sheet explains the decisions and emphasizes enabling lunar surface exploration, commercial capabilities on the International Space Station (ISS) by 2025, key infrastructure repair, and greater IT security expertise. Conversely, it shows a decline in support for Science (-8.7%), Space Operations (-7.6%), Aeronautics (-8.1%), and STEM Engagement (-100%) initiatives. These steep shifts may have been influenced by the launch of a new U.S. representative in space – The United States Space Force.

On December 20, 2019, President Trump’s promises culminated in the creation of a new branch of the U.S. Armed Service, the United States Space Force (USSF), and the eleventh warfighting combatant command, United States Space Command (USSPACECOMM). At the founding ceremony, President Trump reiterated that space is the “world’s newest warfighting domain.” Experts and leaders involved agree that it is “not about putting military service members in space” but about deterrence and maintaining information superiority.

On January 14, 2020, U.S. Air Force (USAF) Gen. Jay Raymond was sworn in as the Space Force’s first-ever Chief of Space Operations and will serve on the Joint Chiefs of Staff. While the logistics of this new combatant command is unclear, what is clear about the USSF is threefold: First, the USSF will operate under the umbrella of the USAF. Second, over the next 18 months the Pentagon’s space programs—most of which are currently housed under Air Force Space Command—and 16,000 officers, airmen and civilians are to be relocated to the USSF. Finally, the creation of a military service dedicated to defending U.S. national security in the “new warfighting domain” sends a definitive message of renewed competition over space that, given today’s economic interconnectivity and political tensions, may not end as well for the United States as it once did in 1969.

Despite valid concerns, there are four notable incentives for the United States and China to pursue equal cooperation in the space domain:

By excluding CNSA’s participation, the current Chinese space program is not bound by international monitoring standards. In 2007, Beijing formally requested admittance to the International Space Station program but was eventually rejected three years later, mainly due to the United States’ national security concerns regarding intellectual property theft and its military applications. China is not an ISS partner and was even legally banned by the U.S. Congress from the ISS from 2011-2013. This exclusion pushed CNSA to independently and rapidly develop its own means to achieve space presence under its own system. For example, in a widely-televised event in September 2011, China launched its first space station complex—TianGong-1—that soon became permanently crewed.

While Washington’s concerns are well-founded, their denial has also pushed China towards other potential partners like Russia and Germany and away from the United States’ sphere of influence. Encouraging CNSA to become active in the ISS program—such as inviting Chinese astronauts to visit the ISS for the first time—would increase potential cooperation and bilateral accountability in this new domain, subsequently achieving greater national security for all participants.

The unknown depths of outer space have long been revered as a promising savior to Earth’s natural resource crisis. From the sinking of Indonesia’s capital city of Jakarta to record-breaking ocean temperatures and colossal bushfires still raging in Australia, 2019 was a year of unprecedented environmental devastation and degradation. Five separate datasets now agree that 2019 was the second-hottest year in 150 years of records. Pressure to pursue sustainable living practices has grown for world leaders and is harder to ignore.

Discovering water outside of Earth is a top priority and within reach. For example, exploration has found large icy pits on Earth’s moon where water and other chemicals may exist. Zheng Yongchun, a researcher at the National Observatory of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, describes the cratered “cold traps” as holding “important resources that humans need to develop and use on the moon for long-term survival.” Also, NASA has been monitoring Mars’ swirling northern ice cap since it was first photographed in 1999 – attesting to the presence of water on the moon. NASA also released maps in December 2019 depicting newly discovered areas of near-surface water on Mars, calling it a “treasure map.”

The U.S. and China can capitalize on these scientific discoveries and jointly endeavor to translate them into actionable climate restoration initiatives and thereby establish common ground that both diplomatic hawks and doves can agree upon. Since the U.S. under the Trump Administration has faced harsh criticism over its rejection of environmental concerns, cooperation on this front could prove to be a welcomed shift despite the geopolitical context on Earth.

The space domain in the 20th century was defined by a nationalistic political culture focused on scientific endeavors rather than a competitive market or space-based warfare. This narrative has historically encouraged space to be a rare point of commonality between nations. Steering towards this narrative—and away from the current militarization narrative propagated by President Trump—could isolate space cooperation from other sociopolitical conflicts and disagreements. Unfortunately, the actions that the Trump Administration has taken regarding space do not suggest a turn towards cooperation and could prove harmful in some aspects of U.S. national security.

The most evident example of multinational cooperation is the International Space Station. The ISS has brought the world together in the spirit of joint exploration and tangible cooperation since agreements were signed between 15 nations in 1998. Visitation rights to the ISS are not limited to ISS partners and 19 nations have been represented in ISS crew rotations.

NASA also has formal, long-lasting partnerships with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), and the European Space Agency (ESA). USSPACECOMM Commander Raymond directly named France, Germany, Japan, and the United States’ Five Eyes partners (Great Britain, New Zealand, Australia, and Canada) as vital partners in space.

CNSA is not an isolationist in space exploration either. As stated in their 2006 White Paper [CHN] on space, between 2001 and 2006 China signed 16 international space cooperation agreements with 13 different countries, space agencies and international organizations. Between 2011 and 2016, that number increased to 43 agreements with 29 partners. Aside from China and the United States, India, Japan and the United Arab Emirates are also “vying to become space powers” through manned and robotic missions to the moon and beyond, making them viable partners in space as well.

There is also precedence for cooperating on space matters with adversaries. During the mid-1970s, in the midst of the Cold War, NASA conducted the joint Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP) with Soviet specialists, marking the first time that a Russian space technician visited NASA’s Johnson Space Center. In present day, astronauts from NASA and Moscow’s Roscosmos State Corporation for Space Activities (Roscosmos) still “get along nicely” despite recent turbulence. For example, in late 2018 and late 2019, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine and the head of Roscosmos Dmitry Rogozin exchanged unprecedented invitations to each of their countries to discuss future cooperation, though the initial invitation extended by Bridenstine was rescinded by the Trump Administration.

The equation for manned missions is still far from perfected, and China has yet to send a man to the moon. According to ChinaPower, about 33 percent of China’s space budget is dedicated to manned spaceflight. In October 2019, the state-owned China Academy of Space Technology (CAST) released a promotion video providing an update on their new-generation crewed craft “capable of deep-space travel.” Professor Joan Johnson-Freese at the U.S. Naval War College explains that “China is committed to long-term human spaceflight at a slow but consistent pace.”

Meanwhile, NASA’s Artemis Mission recently accelerated its plans to return astronauts to the Moon by 2024. Trump’s FY 2021 presidential budget document released in February 2020 called returning American astronauts to the Moon and establishing a lunar presence “NASA’s top-priority mission.” A supplemental budget request was submitted in May 2019 to add $1.6 billion to the effort of a successful 2024 lunar landing goal. In 2020, aside from continuing to send exploration rovers to the Moon, the Green Run test on launch engines for this mission is expected to be completed.

Both the U.S. and China have ambitious Mars landing missions at the forefront of their space programs. SpaceX is focused on its Starship project—a spacecraft built “to help colonize Mars”—that it ambitiously aims to reach orbit by mid-2020. Among other successes, CNSA, which began work on its Mars mission in 2016, successfully completed a test run of its Mars rover last November and subsequently reported that the agency is on track to send a mission to Mars in 2020. Multinational visitations to China’s “Mars Base 1,” their simulated research space-station in their Gobi Desert, could prove productive for all parties involved and be a tangible show of cooperation. Both nations have tools and expertise to contribute which, if combined, could prove far more beneficial than any short-term gratification of space domination.

Of all contemporary American-led space endeavors, one of the most anticipated is the Lunar Gateway announced by NASA in November 2018. A part of NASA’s multinational Artemis program, the Gateway is described as a “small spaceship” that will be placed within lunar orbit to provide ports, short-term living quarters and other materials necessary for scientific exploration. NASA is also in the midst of testing its gargantuan Space Launch System, which could propel astronauts and building materials to the construction area of the Lunar Gateway. Offering some form of partnership with China, as it already has with select ISS partners in March 2019, could be an important step in grasping long-term influence.

Satellite launches are the most common and varied type of launch in space programs. The last quarter of 2019 was described as “very busy” for China’s space industry, with launches occurring daily at some points of the year. As recently as January 7, China launched its largest carrier rocket—Long March-5—with a ‘mystery’ experimental satellite simply named ‘Communication Technology Experiment’ or TJS (Tōngxìn jìshù shìyàn, 通信技术试验), which is reported to be the heaviest and most advanced of its kind. China is expected to launch at least 40 more satellites in 2020.

On January 7, 2020, the American company SpaceX launched 60 small internet-beaming satellites to join the 100 currently circulating in low-orbit. SpaceX reportedly has 23 more similar Starlink launches planned throughout 2020. Additionally NASA launched its Cygnus spacecraft in mid-February 2020 to the International Space Station, where the U.S. continues to have the primary presence. Given the relative ease of access to satellite technology and the inherent security sensitivities, bilateral cooperation efforts are less likely to succeed in satellite development compared to other points of cooperation. However, the concerns of ‘space junk’ and high-speed satellite collisions are becoming a heavy concern as Earth’s orbital satellite traffic becomes more dense. Satellites from NASA and the U.S. Air Force almost collided this past January and could have crashed on Earth. National space agencies like JAXA are experimenting with electrodynamic tethers (EDTs), magnets, harpoons and nets to remove space junk from Earth’s orbit but the systemic problem is far from resolved.

A purely scientific endeavor, offering CNSA a presence in the ISS community could be a more readily available option. Despite the careful approach required, this extension would be controlled under U.S. guidance and, even if it results in no cooperation, it can be a reliable example of U.S. multilateral cooperation. Just as each country had to sign an Intergovernmental Agreement on Space Station Cooperation with NASA in 1998, CNSA would be expected to sign a similar agreement that clearly outlines expectations and limitations of cooperation.

CNSA began constructing its permanent manned space station Tiangong in mid-2019 and is expecting it to be fully operational by the year 2022. There are currently no public announcements offering invitations for other nations to visit Tiangong. Speed is essential to at least establish a semblance of mutual access to both space stations. The upcoming 20-year anniversary of the ISS in November 2020 could prove useful in opening this opportunity to CNSA astronauts.

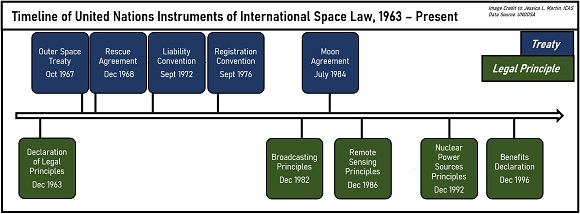

Since outer space can be categorized as international commons, the United Nations (UN) quickly realized the need to set guidelines for the space domain. Since 1963, the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) forum has established five international treaties and five sets of principles on space-related activities that essentially establish non-binding expectations and stress international cooperation. The “Moon Agreement” (1984) was the last treaty adopted and is the most quoted of the ten.

An Observer in The Guardian insists the UN-approved treaty be updated with the creation of an “international space authority” to enforce these new binding rules. The last decade has demonstrated increased independence in space exploration that can be interpreted as a renewed space race. If the U.S. and China continue to develop separately, analyst Rob Ronci envisions a bipolar or multipolar space order based on competitive advantage rather than a hegemonic center with the U.S. at its core. Washington should stress this incentive structure to counter any backlash it may receive from concerned parties for establishing joint projects with CNSA. Unfortunately, the current Administration’s decisions to rescind from international agreements like the Paris Agreement, Trans-Pacific Partnership, and Iran Nuclear Deal, indicate a low likelihood that a space authority could be successfully implemented in the present political environment.

Since the Chinese language often has a wider breadth of meaning than most Western languages, accurate phrasing in any translation is key. Using the Moon Treaty as an example, Dr. Guoyu Wang of the Beijing Institute of Technology detailed how understanding Chinese terminology in legal text can lead to detrimental “mismatched translation” and “misunderstanding.” For example, the eight-part Phase One trade deal that was recently signed on January 15, 2020 serves as non-binding policy support for willing cooperation between Beijing and Washington. The entirety of Article 2.5 states that “[t]he Parties agree to carry out scientific and technological cooperation where appropriate.” The Chinese language version of Article 2.5 expresses the same meaning. While the statement is admittedly vague, it is a formalized acknowledgement of cooperation that could have been excluded altogether.

A tangible first step in lowering barriers to cooperation would be to rescind or modify the Wolf Amendment introduced in 2011. This bill, which specifies that no government funding for NASA and its related agencies can be used to “participate, collaborate, or coordinate bilaterally in any way with China or any Chinese-owned company,” could be up for reconsideration in fiscal year 2020.

NASA cannot “develop, design, plan, promulgate, implement, or execute a bilateral policy, program, order, or contract of any kind to participate, collaborate or coordinate bilaterally in any way with China or any Chinese-owned company.”

– “the Wolf Amendment” (Public Law 112-55), Section 539

Initially added as a preventative measure against technology theft, many experts believe that the Wolf Amendment is doing far more harm than good. Makena Young, a research associate with the Aerospace Security Project at CSIS, believes the Wolf Amendment was ineffective and that, instead of deterring China, it has “only incentivized China to accelerate its space development programs, creating a serious challenger to U.S. leadership in this vital domain of exploration.” In October 2019, space industry consultant Rob Ronci presented a paper at the 70th International Astronautical Congress detailing how the Wolf Amendment is impacting the “developing system of global space governance.” He concluded that, while it does not make cooperation impossible, “it perpetuates an effective perception that the two nations do not, and should not, work together…and that the U.S. should fear losing its outer space dominance.”

These four incentives for cooperation do not disregard the importance of caution, but history has shown how caution can easily lead to inaction. Rather than China pushing its popularized win-win cooperation ideology, negotiations must adopt equally beneficial cooperation as common rhetoric with stepladder demonstrations of bilateral adherence to agreements.

Going forward, experts must watch where the intersect lies between NASA, the U.S. Air Force Space Command, USSPACECOMM, and private sector contractors (i.e. SpaceX, Boeing, Blue Origin). It will be important for the Pentagon and the White House to jointly control the narrative. As the US Space Command bureaucratically matures, more about its mission set will also be revealed. Furthermore, aside from potential presidential campaign announcements later this year that relate to space policy, 2020 will be a year to measure the actual progress of space capabilities as deadlines for mission goals are either met or extended.

Either out of tactical necessity or genuine desire, Beijing’s white papers on space detail the vital nature of international cooperation in space. It is the United States’ turn to extend a hand to Beijing in a productive way and test the CNSA on adhering to its promises of “equal rights to peacefully explore, develop and utilize outer space,” as promised in the 2016 white paper.

There are no perfect solutions in international relations. Regardless of the status of relations, national defense protocols limited to isolation and punishment are slow-burning time-bombs destined to breed greater trouble down the line. These consequences can still be alleviated by applying a holistic and cooperative perspective in space policy. Therefore, the goal of U.S.-China relations in the space domain must be to find a solution that works towards the long-term goal of establishing amicable understandings between China and the United States. Tactical, incremental shifts and extended hands may prove to be a starting point and compromises will need to be made on both sides. Applied alongside deliberate security measures, these tactical steps could mitigate the threat posed by China’s space program while maintaining the narrative of cooperative progress in the space domain. Waves of change are on the horizon and the position of U.S. space dominance will rely on how U.S. space policy is handled over the next 4-10 years.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2025 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

The U.S. Auto Industry Has Not Lost Yet—But It Must Compete Smarter