Resident Senior Fellow

Cover Image: Yasukuni Shrine located in Chiyoda, Tokyo. Photo Credit: Wikipedia Commons 1.0, Wiiii

On August 15, 2020, at the 75th anniversary commemoration of the end of World War II, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe delivered a eulogy to the dead which was astonishing in its lack of, both, acknowledgement of Japan’s historical war responsibility and atonement for the damage and suffering visited upon its Asian neighbors. By contrast, then-Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama had delivered a moving statement on the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II in which he expressed his feelings of “deep remorse and … heartfelt apology” for Imperial Japan’s colonial rule and aggression in Asia.

Prime Minister Abe’s – and the hardline Japanese conservatives’ – lack of contrition is neither new nor remarkable. In their view, while Imperial Japan had committed acts of aggression, the country had waged no blanket war of aggression in Asia. Imperial Japan’s motives had been pure and its actions, furthermore, were employed within a context of overpowering Western colonial rule in Asia. Two landmark documents set twenty years apart – the June 1995 National Diet Resolution and the Abe Statement of August 2015 – provide a window into this running thread of denialism.

The Imperial Rescript of December 1941, issued by the Showa Emperor (Hirohito), has stood at the heart of the revisionists’ case that Japan had only pursued its rightful aspirations of domestic modernization and Asian leadership, and that in the face of Chinese recklessness and Western prejudice and obstructionism, it had waged a war of self-defense on the continent. In truth, the drivers of Imperial Japan’s colonial push in Asia bore tones reminiscent of the Monroe Doctrine wherein Tokyo arbitrarily took upon itself the special responsibility for “the preservation of a peaceful order in East Asia … single-handedly”.

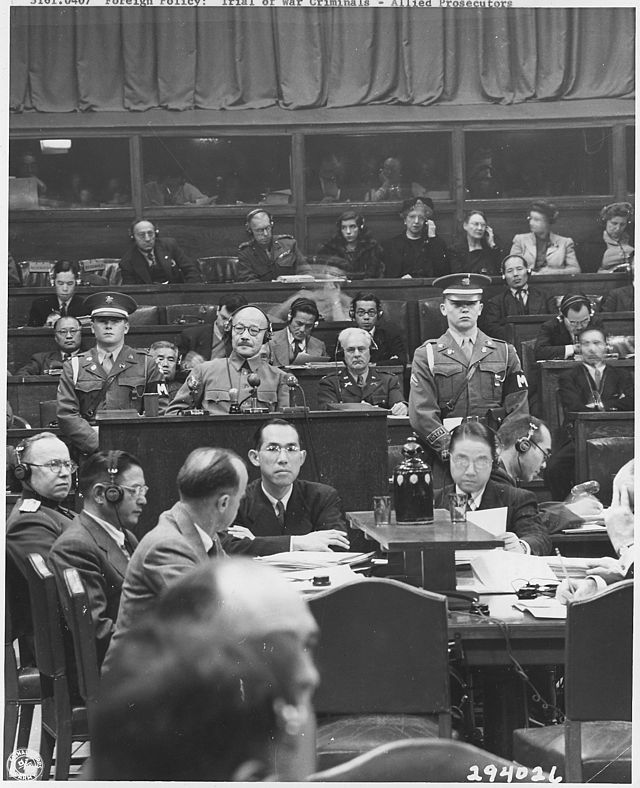

In no small measure, the victor’s justice meted out at the Tokyo War Crimes Trials has been a key stumbling block to hardline Japanese conservatives’ coming to terms with Imperial Japan’s historical wrongdoings. At the Trials, the country was punished for acts that were somehow deemed criminal even though they had not yet been established in international law to be illegal, and a false equivalence was painted too with Nazi crimes.

75 years on, as a younger and less-repentant generation of Japanese politicians and opinion leaders carry the torch of war remembrance forward, the high watermark of atonement for past misdeeds in Asia – and the opportunity for reconciliation – has almost-certainly passed. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s 75th anniversary address is a reflection of this bleak reality.

On August 15, 2020, Japan commemorated the landmark 75th anniversary of its surrender in the Pacific War, which brought down the curtains on World War II. At a solemn government-sponsored ceremony in central Tokyo that has been a staple of war remembrance since 1963, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe delivered a eulogy to the dead. The address was astonishing in that it utterly lacked both an acknowledgement of Japan’s historical war responsibility and contrition for the suffering and horrors visited upon its neighbors. While his Emperor spoke of his “feelings of deep remorse” at the ceremony, Mr. Abe could not bring himself to even utter the words “history” in the course of his remarks. In the prime minister’s reading, the purpose of the August 15th memorial ceremony is to honor the departed souls who fought and died for the state, not atone for the fate of their victims (although he has deviated from this script during past August 15th commemorations). Twenty five years ago by contrast, in a moving statement to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II, then-Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama had humbly acknowledged Imperial Japan’s “mistaken national policy … [which] through its colonial rule and aggression, caused tremendous damage and suffering to the people” of Asia. Mr. Murayama went on thereafter to express his feelings of “deep remorse and … heartfelt apology.” To this day, it is widely recognized as the most far-reaching statement of atonement by a Japanese Prime Minister.

Prime Minister Abe’s lack of contrition is neither new nor remarkable. To the contrary, the roots of Japan’s war responsibility denialism run deep within the dominant conservative reaches of its political establishment. This Issue Brief will identify the key features of this denialism by highlighting the unmistakable parallels between two momentous, and adulterated, statements of contrition issued by the Government of Japan, set twenty years apart – the June 1995 Diet Resolution and the Abe Statement of August 2015. The two, together, constituted a veritable coming full circle of a disappointing chapter in Japan’s continuing struggle to come to terms with its imperial past. The Brief will conclude with an examination of the roots of the hardline conservatives’ denial of Imperial Japan’s aggression in Asia.

In the gracious presence of Their Majesties the Emperor and Empress, and with the attendance of bereaved families of the war dead and distinguished representatives of all sectors of society, I hereby commence the annual National Memorial Ceremony for the War Dead.

More than three million of our compatriots lost their lives during the war, which was extremely fierce and harsh. Some fell on the battlefields worrying about the future of their homeland and wishing for the happiness of their families. Others perished in remote foreign countries after the war. The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the air raids on Tokyo and other cities, and the ground battles in Okinawa, among others, took a heavy toll without mercy. Here, before the souls of all who lost their lives, I offer my heartfelt prayers for their repose.

Again now on the 75th anniversary of the end of the war, we will never forget that the peace and prosperity we enjoy today was built atop the precious sacrifices of the war dead. I express my deepest respect and gratitude once more. Never will we forget the large number of war dead whose remains have still not been recovered. Taking it as the responsibility of the nation, we shall spare no effort to enable their remains to return to their hometowns at the earliest possible time.

Over the 75 years since the end of the war, Japan has consistently walked the path of a country that values peace. We have worked to the very best of our ability to transform the world into a better place. We must never again repeat the devastation of war. We will continue to remain committed to this resolute pledge. Under the banner of “Proactive Contribution to Peace,” we are determined to join hands with the international community and play a greater role than ever before in resolving the various challenges facing the world. We shall overcome the current novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and carve out the future of our nation for the sake of the generation alive now and the generations of tomorrow.

I will conclude my address by once again offering my heartfelt prayers for the repose of the souls of the war dead and for the happiness of the members of their bereaved families.

The world has seen fifty years elapse since the war came to an end. Now, when I remember the many people both at home and abroad who fell victim to war, my heart is overwhelmed by a flood of emotions.

The peace and prosperity of today were built as Japan overcame great difficulty to arise from a devastated land after defeat in the war. That achievement is something of which we are proud, and let me herein express my heartfelt admiration for the wisdom and untiring effort of each and every one of our citizens. Let me also express once again my profound gratitude for the indispensable support and assistance extended to Japan by the countries of the world, beginning with the United States of America. I am also delighted that we have been able to build the friendly relations which we enjoy today with the neighboring countries of the Asia-Pacific region, the United States and the countries of Europe.

Now that Japan has come to enjoy peace and abundance, we tend to overlook the pricelessness and blessings of peace. Our task is to convey to younger generations the horrors of war, so that we never repeat the errors in our history. I believe that, as we join hands, especially with the peoples of neighboring countries, to ensure true peace in the Asia-Pacific region -indeed, in the entire world- it is necessary, more than anything else, that we foster relations with all countries based on deep understanding and trust. Guided by this conviction, the Government has launched the Peace, Friendship and Exchange Initiative, which consists of two parts promoting: support for historical research into relations in the modern era between Japan and the neighboring countries of Asia and elsewhere; and rapid expansion of exchanges with those countries. Furthermore, I will continue in all sincerity to do my utmost in efforts being made on the issues arisen from the war, in order to further strengthen the relations of trust between Japan and those countries.

Now, upon this historic occasion of the 50th anniversary of the war’s end, we should bear in mind that we must look into the past to learn from the lessons of history, and ensure that we do not stray from the path to the peace and prosperity of human society in the future.

During a certain period in the not too distant past, Japan, following a mistaken national policy, advanced along the road to war, only to ensnare the Japanese people in a fateful crisis, and, through its colonial rule and aggression, caused tremendous damage and suffering to the people of many countries, particularly to those of Asian nations. In the hope that no such mistake be made in the future, I regard, in a spirit of humility, these irrefutable facts of history, and express here once again my feelings of deep remorse and state my heartfelt apology. Allow me also to express my feelings of profound mourning for all victims, both at home and abroad, of that history.

Building from our deep remorse on this occasion of the 50th anniversary of the end of the war, Japan must eliminate self-righteous nationalism, promote international coordination as a responsible member of the international community and, thereby, advance the principles of peace and democracy. At the same time, as the only country to have experienced the devastation of atomic bombing, Japan, with a view to the ultimate elimination of nuclear weapons, must actively strive to further global disarmament in areas such as the strengthening of the nuclear non-proliferation regime. It is my conviction that in this way alone can Japan atone for its past and lay to rest the spirits of those who perished.

It is said that one can rely on good faith. And so, at this time of remembrance, I declare to the people of Japan and abroad my intention to make good faith the foundation of our Government policy, and this is my vow.

On June 9, 1995, the House of Representatives of the National Diet adopted the Resolution to Renew the Determination for Peace on the Basis of Lessons Learned from History to mark the 50th anniversary of the end of the Pacific War. To this day, the Resolution stands as the lone one ever crafted by the Diet – the highest legislative body in the land where the sovereignty of the Japanese people resides – to convey remorse for Imperial Japan’s misdeeds. The resolution was atypical in many respects. Procedurally, Diet resolutions are adopted unanimously in principle. The 1995 resolution, however, was adopted by less than half the members of the House of Representatives, with many ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) legislators absenting themselves from the vote, including a first-term parliamentarian by the name of Shinzo Abe. The entire membership of the largest opposition party, Shinshinto, too stayed away. Fearing an equally bleak performance in the House of Councilors, the then-Socialist Party prime minister, Tomiichi Murayama, cut short the legislative effort and proceeded to issue a Cabinet Decision bearing his name two months later. The LDP members within the cabinet dared not to subvert the Cabinet Decision for fear of bringing down the governing coalition prematurely. Substantively, the resolution constituted the first ever admission, albeit an indirect and half-hearted one, by Japan’s supreme legislative body that Imperial Japan had committed aggression in Asia.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s Statement twenty years later entailed, by contrast, no legislative skullduggery. Despite his government’s two-thirds majority in the Diet, the body was not pressed into service into issuing a resolution. The Statement was issued instead in the name of the prime minister on the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II. The Abe Statement was unusually long for a document of its kind – and long in coming too. Ever since Prime Minister Abe was re-elected to office in December 2012 and had promised in 2013 to issue a “forward-looking” 70th anniversary end-of-war statement, its content was awaited with anticipation and trepidation, given his plainly revisionist personal leanings. Intense interest had zeroed-in on whether he would repeat the key words, colonial rule and aggression, deep remorse and heartfelt apology, used by former Prime Minister Murayama in the 50th anniversary statement. Mr. Abe’s two previous August 15th statements since his December 2012 re-election had not been profiles in atonement. In both instances, he dropped the customary reference to Japan’s war responsibility and the promise not to wage war. In keeping with his prior revisionist views, he had instead incongruously and insensitively remembered Japan’s war victims on the continent and pledged never to wage war at the Yasukuni Shrine in December 2013 – a venue that was seen as a slap in the face of the victims of Japanese invasion and colonial rule.

In the event, the consensus view of the Abe Statement was that it was politically ‘better than it might have been, but worse than it should have been’. While it left no domestic or international constituency satisfied, it did not bear a generally revisionist imprint either. The intensely anticipated key words were (indirectly) reconfirmed, the nations of Asia that suffered were directly listed, and content was endowed to Prime Minister Murayama’s abstract description of Imperial Japan as “having made mistaken policy”. This having been said, there were notable deficiencies in the Abe Statement too. It frequently resorted to the anonymous passive voice, with its connotation of avoidance of direct responsibility when touching on the most sensitive subjects. More to the point, the Statement, like the 1995 Diet Resolution, glided elliptically around the harshest truths that post-war Japan has yet to own up to (see ensuing discussion) – in turn highlighting, both, why admitting to aggression in Asia is such a heavy lift in Tokyo and also how little the ground has shifted in important respects in the hardline conservatives’ view of Imperial Japan’s aggression in Asia.

First, both the 1995 Resolution and the 2015 Statement frame – and thereby diminish – the culpability of Imperial Japan’s actions within a context of emphasizing overpowering Western colonial rule in Asia. There is no unilateral incrimination of Imperial Japan’s misdeeds in Asia. The country, rather, as per both documents had been sucked into an imperial vortex not of its own creation. The 1995 Resolution goes so far as to insinuate that Tokyo’s actions were incidental to that of the West – that there had been many instances of colonialism and aggression in modern times and Japan had also gotten caught up in such acts, especially in Asia. The 2015 Abe Statement too lays the initial onus of Imperial Japan’s downward spiral on the West’s actions. In this case, the rise of protectionist Western trading blocs following the Great Depression drove Tokyo to create its own defensive sphere of economic interest in Asia. As the Statement laments:

However, with the Great Depression setting in and the Western countries launching economic blocs by involving colonial economies, Japan’s economy suffered a major blow. In such circumstances, Japan’s sense of isolation deepened and it attempted to overcome its diplomatic and economic deadlock through the use of force. Its domestic political system could not serve as a brake to stop such attempts. In this way, Japan lost sight of the overall trends in the world.

In truth, the drivers of Japan’s imperial push in East Asia in the 1930s run far deeper. Its philosophical bases emerged from a geo-historical view drawn from German political thought that long pre-dated the Great Depression and which postulated an emerging world order consisting of three or four economically and politically autonomous regional blocs. Each bloc leader would bear the responsibility for the maintenance of peace and order within its area. In tones reminiscent of the Monroe Doctrine, Imperial Japan took upon itself the special responsibility (as articulated by the Amou Doctrine of April 1934) for “the preservation of a peaceful order in East Asia … single-handedly” – ironically at about just the same time Franklin Roosevelt was ushering in his administration’s ‘Good Neighbor’ policy towards Latin America. Non-Asian interlopers were to be excluded from intervening in the monetary, financial and military affairs of China.

Second, both the 1995 Resolution and the 2015 Abe Statement obscure the fact, to varying degrees, that Japan was the country that committed aggression and carried out colonial rule in Asia. In the 1995 Diet Resolution, Japan is neither identified directly as the perpetrator of Asia’s victimization nor are Asian nations directly specified as its victims. As the Resolution states:

Solemnly reflecting upon many instances of colonial rule and acts of aggression in the modern history of the world, and recognizing that Japan carried out those acts in the past, inflicting pain and suffering upon the peoples of other countries, especially in Asia, the Members of this House express a sense of deep remorse.

Nor was an apology forthcoming; the Diet could only come to express remorse for the acts committed. The Abe Statement is more forthright in acknowledging the immense suffering visited upon Asians, both in East and Southeast Asia, yet here too again it blurs the line between victim and victimizer. It is not clear whether “colonial rule” and “aggression” are mentioned therein as acts committed by Japan or only in general terms. The apology tendered is indirect too, in that it mentions past cabinet statements which expressed these sentiments but is not offered in Mr. Abe’s voice (“Japan has repeatedly expressed the feelings of deep remorse and heartfelt apology for its actions during the war … such position articulated by the previous cabinets will remain unshakable into the future”).

Third, the long-suffering ‘comfort women’ find little or no solace in either document. The specific reference to comfort women and the forcible recruitment of laborers was edited out in the final 1995 Resolution. For all his claims to ‘engrave in his heart the injuries suffered to their honor and dignity’, the Abe Statement too fails to identify the ‘comfort women’ by name as a group – let alone atone directly to them for the emotional suffering endured.

By far, the most noteworthy parallel between the 1995 Diet Resolution and the 2015 Abe Statement relates to the treatment of the hotly contested word ‘aggression’. In the 1995 Diet Resolution, the draft term “war of aggression” was expressly downgraded to the more circumscribed “acts of aggression.” Yes, Imperial Japan did undeniably commit acts of atrocity, i.e. instances of aggression, in the course of defending its pre-eminent rights and interests on the Asian continent. The country had waged no blanket war of aggression however and any such all-encompassing characterization of Japanese intent and purposes was totally inadmissible. On his return to the premiership in December 2012, Mr. Abe appeared to tip-toe around this view. He argued that the term “aggression/invasion” had not been defined academically or internationally and as a politician he would not pry into that definition. By mid-summer 2013, he had backtracked to vaguely note that while he never said that Japan did not conduct military aggression, he was not in a position to define what those actions constituted!

No such contortion or ambiguity was on display at his press conference following the release of the Abe Statement on August 14th, 2015. While the word ‘aggression’ is not prefaced with the words ‘war of’ or ‘acts of’ in the Abe Statement (or, for the matter, in the Murayama Statement of August 1995), Prime Minister Abe was forthright in stating that while “there were acts [committed by Imperial Japan] that can be considered aggression … the matter of [which] specific acts can be called aggression or not should be left up to discussions by historians.” Imperial Japan, by implication, had certainly waged no war of aggression in Asia; even individual acts that could be construed as aggression was a matter on which no historical consensus had been reached. Far from acknowledging – and atoning – for the ideological bases of aggression on the Asian continent, Japan’s motives had in fact been pure. It had just so happened that protectionism and Japan’s economic isolation at the time, paired with shortcomings within its domestic political system, had conspired to launch the country on a path that “[lost] sight of the overall trends in the world” and from which there was no exit.

The 1995 Diet Resolution and the 2015 Abe Statement provide a window into the deeper roots of Japanese nationalists and revisionists’ continuing denial that Imperial Japan had waged a ‘war of aggression’ in Asia. The denial traces its origin to the Imperial Rescript of December 1941, issued by the Showa Emperor (Hirohito), that had accompanied Japan’s declaration of war. In the Imperial Rescript, the Showa Emperor had complained:

“More than four years have passed since China, failing to comprehend the true intentions of Our Empire, and recklessly courting trouble, disturbed the peace of East Asia and compelled Our Empire to take up arms … the regime which has survived at Chungking, relying upon American and British protection, still continues its fratricidal opposition. Eager for the realization of their inordinate ambition to dominate the Orient, both America and Britain, giving support to the Chungking regime, have aggravated the disturbances in East Asia … They have obstructed by every means our peaceful commerce, and finally resorted to a direct severance of economic relations, menacing gravely the existence of Our Empire. Patiently have We waited and long have We endured, in the hope that Our Government might retrieve the situation in peace. But our adversaries, showing not the least spirit of conciliation, have unduly delayed a settlement; and in the meantime, they have intensified the economic and political pressure to compel thereby Our Empire to submission.”

China, failing to comprehend Japan’s true and friendly intentions, had disturbed the peace, and the U.S. and the British Empire had shown not the least bit of conciliation. To the contrary, they had intensified economic and political pressure on Japan to coerce its submission. In Imperial Japan’s view, the government had waited patiently and endured long but circumstances had now forced its hand to declare war. The Imperial Rescript has stood at the heart of the revisionists’ case that Japan did not seek confrontation with others; that it had only pursued its rightful aspirations of domestic modernization and Asian leadership; and that in the face of Western prejudice and obstructionism it had waged a war of self-defense motivated by legitimate concerns for its preeminent rights and interests on the continent. To deny the content and justification of the Rescript would be, in the nationalists’ view, to contradict and diminish the Showa Emperor himself. Worse, it would symbolize disloyalty to a symbol of Japanese public life held in totemic grace through time immemorial. Ominously, it might also re-open the door to examining the Emperor’s ‘war responsibility’ posthumously. It bears noting that the Emperor Hirohito had passed away just six years earlier and a renewed debate over his command responsibility for the war, as constitutional monarch, could not be discounted.

It is an undeniable fact that the domestic accounting of war responsibility has proceeded insufficiently in Japan. In no small measure though, a fair deal of blame also resides on the shoulders of Japan’s American and Western occupiers. Just prior to the Tokyo War Crimes Trials, the Allied Occupation Authorities exonerated the Showa Emperor of war responsibility in exchange for his repudiation, by way of an Imperial Rescript on New Year’s Day 1946, of his pretentious claim to divine descent. That claim had hitherto been the basis of pre-war emperor worship and a fount for ultra-nationalist mobilization. At the subsequent Tokyo War Crimes Trials, a controversial new charge of ‘crimes against peace’ was pinned on the highest-ranking Japanese defendants and they were convicted of waging “wars of aggression” to “secure the complete domination of East Asia and the Pacific Ocean and their adjoining countries and neighboring islands.” Waging “aggressive war” was not a crime under prevailing international law and an agreed-upon consensus, let alone definition, of such wars did not exist at the time. The Tribunal itself was a “huge-scale theatrical production” which the American diplomat George Kennan admitted, employed the “hocus-pocus of judicial procedure” without guaranteeing its due process protections. Determined however to buttress the Nuremberg rulings vis-à-vis the Nazis on aggressive war and thereby consolidate the breaking of controversial new legal ground on the ‘criminality of unjust wars’, the charges were made to stick on the Japanese defendants by the prosecuting victorious powers. And by way of Article 11 of the Treaty of Peace with Japan at San Francisco on September 8, 1951, Tokyo was formally forced to acquiesce to the Trials’ verdict in return for the end of the military occupation and the restoration of its sovereignty.

Yet formal acquiescence did little – and has done little – to engender a sense of reflection among hardline conservatives in Tokyo. To the contrary, the contorted logic which punished Japan for acts that were somehow deemed criminal even though they had not yet been established in international law to be illegal, and painted a false equivalence with Nazi crimes, has nurtured a deep-seated resentment which continues to find expression in adulterated apologies – such as the 1995 Diet Resolution and the 2015 Abe Statement – by the conservatives-led Japanese political establishment. Perhaps, had Japan been assigned “its share of responsibility – [not the entire responsibility] – for precipitating a war of aggression into which her people were deceived and misled by irresponsible and self-willed militarists”, as the Canadian delegation to the Japanese Peace Treaty consultations had suggested, the view in Tokyo on Imperial Japan’s ‘war responsibility’ might have been less defensive and more forthright and apologetic.

75 years on, as a younger and less-repentant generation of politicians and opinion leaders carry the torch of war remembrance forward, the high watermark of Japanese atonement for the misdeeds that sustained a deeply-flawed fascist enterprise of territorial aggrandizement on the Asian continent has almost-certainly passed. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s 75th anniversary address on April 15th is a reflection of this bleak reality – and of the opportunity for reconciliation that has been lost for good, perhaps.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2025 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

With Kishida’s Resignation, Japan Brings More Economic Uncertainties to Asia in a U.S. Election Year