Research Associate & Program Officer

Research Associate & Administrative Officer

On Tuesday, April 26, 2022, ICAS delivered a briefing held at a United Nations seminar for delegates from over 60 UN Missions on how small island states can utilize satellite imagery and GIS applications to demarcate existing land territory and maritime zones amid rising sea levels. This issue brief summarizes the research led by ICAS scholars for that purpose.

Sea-level rise threatens the environment of island countries disproportionately. It presents increasingly urgent political complications as they face an imminent need to record and submit international evidence to prove their existing baselines.

Noticing the pressing need from dozens of island countries to produce evidence and records of maritime zones, scholars at the Institute for China-America Studies (ICAS) launched a special research project to explore technology solutions to this issue.

Combining High-resolution satellite imagery (HRSI) with a Geographic Information System (GIS) for mapping baselines and maritime zones for small island developing countries provides a relatively low-cost way for governments to achieve this.

Obtaining the most accurate high-resolution imagery will require a financial investment. Fortunately, these costs are far less expensive when compared to traditional methodologies of measuring maritime zones.

The findings suggest that island countries could cooperate with non-profits, universities, and companies to borrow the know-how from the world’s most advanced experts to significantly reduce the barriers to accessing these resources.

Maritime zone demarcation methodologies stemming from satellite technologies provide cost-effective solutions and ought to be seriously explored. Without consideration of novel pathways, sea-level rise and climate change will force UNCLOS signatories to adapt to harsh realities with severe legal implications as their coastlines recede.

Climate change and global warming impact island countries disproportionately. The mean global sea-level rise rose from 2.1mm per year between 1993 and 2002 to 4.4 mm per year between 2013 and 2021. According to “Antigua and Barbuda’s submission on the effects of sea-level rise on the law of the sea” to the International Law Commission, one meter of sea-level rise would result in approximately 1,300 square kilometers of land lost in the Caribbean, which would devastate island nations of the region. Sea-level rise not only threatens the environment of island countries, but also presents increasingly urgent political complications. Small island developing countries face an imminent need to record and submit international evidence to prove their existing baselines, and other maritime zones as debates are ongoing within the United Nations on whether to freeze existing baselines and maritime zones, irrespective of sea-level rise, or to allow new findings based off of novel technology solutions to be submitted.

Most countries measure their baselines based on bathymetric information, which is generally measured and collected by their hydrographic offices, sometimes part of their Navies. That being said, traditional geographic measuring and data collection are highly time-consuming and costly. The time, technical, human resource, and financial constraints significantly limit small island developing countries’ capacity to produce and submit evidence and records critical to protecting their maritime rights and claims.

Noticing the pressing need from dozens of island countries to produce evidence and records of maritime zones, scholars at the Institute for China-America Studies (ICAS) launched a special research project to explore novel methodologies that provide more cost-effective and time-efficient alternatives with fewer technical and human capital barriers when compared to traditional methods. We successfully incorporated high-resolution satellite imagery (HRSI) and a Geographic Information System (GIS) for mapping baselines and maritime zones for small island developing countries. For our study, we randomly selected one low-lying island country from the Caribbean, the Indian Ocean, and the Pacific Ocean, which are Antigua & Barbuda, Maldives, and Kiribati, respectively. In essence, we tested whether combining HRSI with GIS mapping has the potential to reduce the time and financial cost associated with the constraints small island developing states typically face.

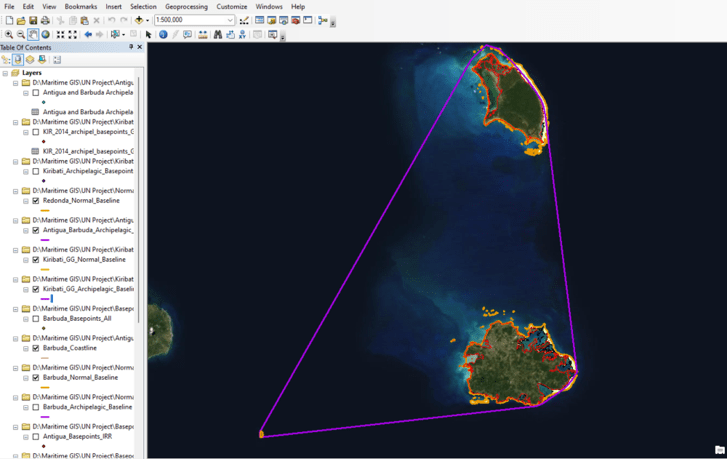

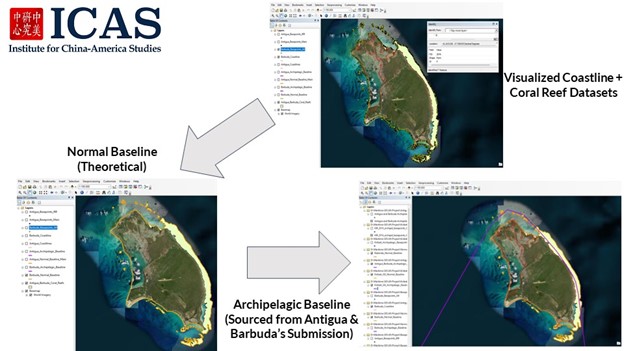

In order to generate unofficial theoretical basepoints and theoretical normal baselines, ICAS scholars made use of a dataset of global shorelines developed by the U.S. National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency in conjunction with the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which is produced by HRSI of the LANDSAT 7 multispectral imagery, and combined with UNEP’s dataset for Global Coral Reef Distribution, as reefs can be fundamental for the correct calculation of maritime areas according to United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) definitions. Both datasets are freely available and in the public domain. The datasets were then converted into informative graphics and divided into different layers through a mapping and analytics platform called ArcGIS. This software utilizes a GIS, a framework used to analyze the spatial location and organize multiple layers of visualizations on maps.

Because the geography of each country studied met the requirements of an archipelago, officially submitted archipelagic baselines were drawn together with an unofficial theoretical normal baseline using GIS software as a point of comparison. An unofficial theoretical baseline was drawn to indicate that the same methodologies can be employed for some island and coastal countries that may not qualify as an archipelagic state based on UNCLOS Articles 46-50. This means that any government can demarcate their maritime zones using these methodologies regardless of whether archipelagic baselines, normal baselines, or straight baselines are incorporated. From here, it would then be possible for any country to demarcate their 12 nautical mile territorial sea limits, the 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone, and other maritime zones of interest using this software. In essence, these methodologies are not explicitly designed for just those countries that could not produce their legal submissions at a feasible cost, but rather that these approaches could be relatively more affordable and valuable to all developing island countries.

Alternatives to traditional geo/hydrographic surveys, which measures the low-tide coastline where baselines and other related maritime zones would stem, must address the time, technology, human resource, and financial constraints that small island developing countries may encounter if they choose the traditional approach. This case study confirmed mapping baselines and maritime zones is feasible through HRSI and GIS. Additionally, this project demonstrates that mapping using these digital resources can lead to enormous time and labor cost savings.

The combination of HRSI and GIS allows mapping to be conducted anytime and anywhere. On the other hand, traditional surveying could take weeks to collect geo- and hydrographic data before processing. Moreover, traditional geo- and hydrographic survey is also easily affected by weather conditions, which should be considered since a significant proportion of the small island developing countries are located around tropical areas. Although satellite imagery can also be impacted by cloud cover, there are technology solutions to this issue as well that can digitally remove visual obstacles from an area of study. Many small island developing countries experience constant heavy rainfall and are relatively vulnerable to unforeseeable maritime natural disasters such as tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, and storm tides. These natural conditions could significantly delay the progress of the traditional survey as drone operations and maritime surface surveying both require relatively benign conditions to proceed.

The combination of HRSI and GIS shows high potential in addressing the technology, human resource, and financial constraints that many small island developing countries may encounter. Traditional surveying methods typically require advanced surveying equipment and data processing software. For instance, the U.S. NOAA survey ship for hydrographic surveys is equipped with a multibeam echo sounder. Employing such technology would be a relatively expensive one-time investment for many small island developing countries. Even for geographic surveys that rely on airborne drones, the processing of the data collected requires investment in big data technology-related hardware and software that drive up the cost significantly. Likewise, the traditional surveying approach also requires a relatively long-term investment to build the specialized human capital, which is not feasible for many small island developing countries. Outsourcing the surveying to private companies would also be a considerable expenditure. Most matured firms work with governments of developed countries through private-public partnerships, which set the benchmark price for their services.

On the other hand, this case study showed that the cost of conducting such mapping could be reduced drastically while still maintaining high quality. Although the datasets ICAS scholars used to generate the visualizations are free sources from the public domain, they already meet the fundamental requirement to correctly display Antigua and Barbuda’s assorted geo- and hydrographic information. Suppose a small island developing country is willing to invest 200 to 500 thousand U.S. dollars to purchase satellite data with higher resolution. In that case, the product could better serve as international evidence with greater accuracy. In addition, many satellite companies provide discounted or free services for scientific research and not-for-profit purposes. Satellite resources have applications outside of just demarcations as well, which could include their use as an enforcement mechanism for maritime zones. Satellites can track commercial vessels of most kinds to ensure compliance with national or international laws such as the International Convention for Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), which makes this an investment for the long term.

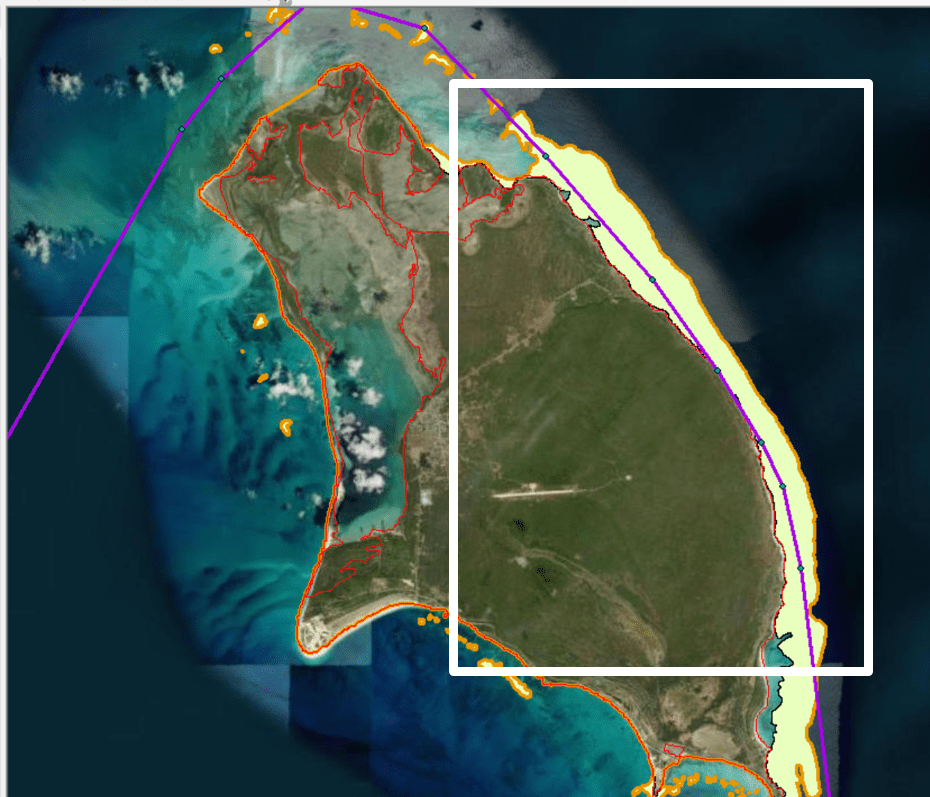

Figure 3 illustrates a visualized comparison was made between Antigua & Barbuda’s 1982 archipelagic baseline coordinates submission (represented by purple lines) and a theoretical normal baseline (represented by orange lines) generated by combining the coastline and coral reef datasets in accordance with the stipulations provided by UNCLOS Articles 3-16 and 46-50, which detail the limits of the territorial sea and the rights of archipelagic states. According to Article 6, islands with fringing coral reef formations allow for baselines to be measured along the seaward low-water line of the reef. As Figure 1 indicates on the bottom-right image, the official submission from Antigua & Barbuda significantly overlaps with the coral reef formation on its eastern coastline, which suggests that its 1982 submission may not provide the full potential that the baseline could have extended. Additionally, some formations exist outside of the archipelagic baseline that has been outlined in the orange theoretical baseline, once again indicating that the full extent of the baseline may not have been reached.

It should be emphasized that these findings are not declarative and warrant further study for confirmation or greater accuracy. The debate on whether past submissions on baseline claims ought to be frozen and irreversible remains ongoing within the United Nations and academic community due to potential legal implications and the possibility of triggering or deepening sovereignty and sovereign rights disputes between countries if maritime zone claims were to expand. Since satellite data stretches back decades, countries that have either already submitted their maritime zones to the UNSG or those that are in the process of doing so may choose to incorporate imagery from different time periods in order to maximize their claims, which could further complicate disputes if a mutually agreed upon time period to conduct measurements is not chosen.

Yet, the fact remains that sea-level rise will forcibly alter the coastlines of island states, making it imperative that the most scientifically and legally accurate baseline measurements be incorporated. There are clear arguments to be made in favor of allowing some form of revision, as the access to new technologies will unfairly advantage those countries that waited to submit their claims, as opposed to those countries that submitted claims several decades ago based upon potentially incomplete data. Even with this debate unsettled, governments do have an incentive to verify or bring up-to-date their maritime zones. Doing so allows for more clarity on jurisdictional and law enforcement operations through coast guards.

Obtaining the most accurate high-resolution imagery will require a financial investment. Fortunately, these costs are far less expensive when compared to traditional methodologies of measuring maritime zones. GIS and high-resolution satellite imagery can provide the ability to accurately demarcate maritime zones at a relatively lower cost, which benefits lower-income and small island states. The only potential limitations are where data and expertise are sourced from. Expertise can be provided by working with nonprofits and universities to minimize costs while maximizing the potential benefits. In addition to purchasing imagery, some companies can provide high-quality data to many university labs and governments for scientific research. Island countries could cooperate with non-profits, universities, and companies to borrow the know-how from the world’s most advanced experts to significantly reduce the barriers to accessing these resources.

Even for countries that have fully submitted their maritime zones to the United Nations Secretary-General (UNSG), it is essential to employ modern methodologies to either review or share these submissions with the public more easily. GIS software allows for greater dissemination of maritime zone submissions so that the public more easily understands them. Maritime zone demarcation methodologies stemming from satellite technologies provide cost-effective solutions and ought to be seriously explored. Without consideration of novel pathways, sea-level rise and climate change will force UNCLOS signatories to adapt to harsh realities as the ocean swallows and shrinks territory, acutely threatening small island states’ security and economic livelihoods.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2025 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

The Nordic Reaction to America’s Arctic Posture