Source: Getty Images

Resident Senior Fellow

Head, Trade 'n Technology Program

‘Industrial policy’ refers to the official strategic effort of a country to encourage the development and growth of its economy, typically by focusing on key sectors within the manufacturing economy. Industrial policy concerns itself with the pattern rather than the scale of capital allocation within the economy.

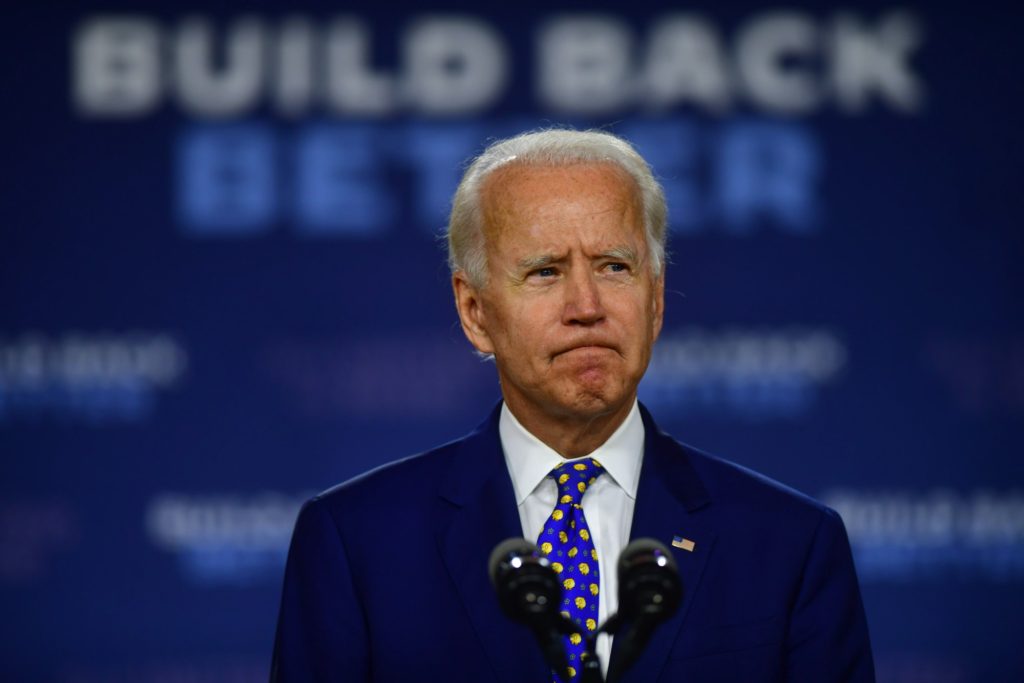

State intervention to steer the industrial economy towards specific industries is not entirely foreign to the United States. The federal government has engaged in subtle and not-so-subtle interventions to incubate ‘missing’ markets and align forces for greater efficiency and market competitiveness. The Biden administration’s planned interventions under its “Build Back Better” agenda and Supply Chain Resilience plan conform with this longstanding federal government role of shaping industrial sector outcomes at home.

The administration’s ‘industrial policy’ effort is framed in the context of its “extreme [strategic] competition” approach towards China. It is geared towards utilizing existing statutory authorities to encourage and expand the domestic advanced manufacturing base, especially for critical supply chains (semiconductors, large-capacity batteries, critical materials, etc.). In this regard, it differs from the Trump administration’s strategic economic policy approach towards China which was overwhelmingly centered on a punitive tariff and technology controls strategy vis-à-vis Beijing.

In addition to a number of competitiveness-related bills awaiting congressional action, the range of envisaged Executive Branch policy interventions extends from a mix of investment incentives; research, production, as well as consumer-facing tax credits; matching cost-share grant and loan programs; expanded procurement preferences; selective imposition of import tariffs; support for basic and applied research; and the leveraging of government-sponsored IP to promote the diffusion of manufacturing technologies.

Some of these industrial policy lines of effort, such as the linking of federal procurement preferences to critical technology products and components, contradict past demands made by U.S. negotiators to their Chinese counterparts. Others, such as the gargantuan scale of proposed subsidies and tax credits as well as their availability based on unionization status and location of product assembly, undercut level playing field market rules or violate the U.S.’ WTO obligations.

President Donald Trump’s China trade and investment policy primarily aimed to leverage all available U.S. conventional and unconventional trade enforcement tools at the White House’s disposal to alter the terms of America’s trading relationship with China. Top of the list was eliminating or reducing the large bilateral trade deficit with China. In his centerpiece economic plan of 2016 to rebuild the American economy and “Make America Great Again”, Candidate Trump had threatened to employ a slew of statutory trade policy enforcement tools against China, including Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 and Section 201 and Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974. Each was imposed in the ensuing years.

In January 2018, President Trump signed a safeguard proclamation under Section 201 of the Trade Act of 1974, imposing tariffs and tariff rate quotas on imports of Chinese (and global) solar cells and modules and manufactured washing machines. The safeguard action was the first in 16 years. On March 8, 2018, Trump imposed a global tariff of 25 percent on steel imports and 10 percent on aluminum imports, following a sweeping national security-related investigation conducted under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. The probe was the first of its kind since an investigation into the effects of iron and steel imports in 2001. On March 23, 2018, Trump announced the findings of an investigation of Chinese technology transfer, intellectual property rights (IPR) and innovation practices under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, pursuant to which a first tranche of tariffs was imposed on July 6, 2018. The Section 301 action was the first such action in more than a quarter century. And starting May 15, 2019, President Trump proceeded to impose a number of technology controls-related sanctions on China too, including the imposition of an expansive Information and Communications Technology and Services (ICTS) Supply Chain Rule and Foreign ‘Direct Product Rule’ to disadvantage Huawei. For added measure, China was formally labeled a “currency manipulator” on August 5, 2019.

In the event, the numerous enforcement actions inflicted as much damage to the U.S.’ commercial interests in China and to U.S. trade leadership authority in the world as they did to China. Worse, the bilateral trade deficit at the start of the Trump term, (US$ 346 billion in December 2016), remained more-or-less unchanged towards the latter part of the Trump term (US$ 344 billion in December 2019).

President Joseph Biden has reversed many of Mr. Trump’s “America First” policies, including by returning the United States to the Paris Accord and reversing the U.S.’ withdrawal from the World Health Organization (WHO). On the trade, investment and technology policy front though, he has more-or-less continued on the path laid down by Donald Trump, refining rather than revoking the numerous enforcement actions of his predecessor – be it tariffs or export controls-related. But in addition to going down the punitive enforcement route, the Biden administration has also sought to chart an ambitious program of “strategic industrial policy” investments in U.S. industrial capabilities under its “Build Back Better” agenda and Supply Chain Resilience plan. These envisage a range of interventions in American hard and soft infrastructure and capabilities that can support jobs and employment, sharpen America’s competitive edge, and avoid shortages of critical products.

An ‘industrial policy’ refers to the official strategic effort of a country to encourage the development and growth of its economy, typically by focusing on key sectors within the manufacturing economy. Measures are taken that aim to incubate and enhance the capabilities and competitiveness of domestic firms and thereby promote broader economy-wide structural transformation. Industrial policy concerns itself with the pattern of capital allocation rather than the scale of capital allocation within the economy. As such, it favors industrial sectors that are internationally competitive and generate positive economy-wide spillovers, while also helping to develop national infrastructure (ports, roads, broadband connectivity) and a skilled work force.

The term East Asian ‘miracle’ refers to the remarkable rise of the Asian Tiger economies (Hong Kong, South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan) from poverty to high-income status in the short span of four decades. They are the only four post-colonial economies in the past half-century to have scaled high-income status without the blessing of natural resource discoveries. China is only the latest East Asian ‘miracle’ economy, standing on the cusp of joining this rarified group.

‘Industrial policy’, particularly the state-guided emphasis on investment and innovation-driven growth to sustain high productivity gains, has been credited with the remarkable rise of the Asian Tigers. Three state-led interventions were key. First, the state set ambitious industrial and manufacturing sector goals and intervened thereafter to facilitate the move of domestic firms into higher sophistication sectors, both consistent with and even beyond existing comparative advantage. Next, firms were compelled to develop an export orientation and outcompete their peers on the basis of innovation and cost. Finally, market discipline and accountability were enforced strictly. As the country leapt “technologically beyond comparative advantage and the more this technology was produced by domestic firms,” the greater the likelihood was of a sustained high productivity and high-speed growth outcome.

Source: Reda Cherif and Fuad Hasanov, “The Return of the Policy that Shall Not be Named: Principles of Industrial Policy,” International Monetary Fund, Working Paper 19/74, March 2019

The term ‘industrial policy’ is a familiar one to Europeans and Japanese. State intervention to steer the industrial economy towards specific sectors is not entirely foreign to the United States either. Although the term is one from which American policymakers instinctively repel, the fact of the matter is that industrial policy has had a longstanding role in shaping economic outcomes since the birth of the republic. Alexander Hamilton, the first Treasury Secretary, laid out a plan to promote manufacturing to catch up with Great Britain and economic historians have credited the economic dominance of the U.S. to “a stream of visionary market-distorting state interventions” initiated by him and his successors.

The federal government has engaged in subtle and not-so-subtle interventions to incubate ‘missing’ markets and align forces for greater efficiency and market competitiveness. The birth and development of Silicon Valley was generated in large part by the initial customer base and demand arising from the U.S.’ national security needs. And at a time when China’s ‘military-civil fusion’ policies is a cause of angst in Washington, it is worth remembering that NASA used to be the largest consumer for integrated circuits, and that in 1962 NASA and the U.S. Air Force bought 100% of the integrated circuits produced in the world. As the RCA case below demonstrates, the federal government has not been reticent either to use its coercive power to elbow foreign competitors out of sectors deemed to be strategic, such as telecommunications. Huawei and China’s most dynamic AI and computer vision companies, such as Hikvision, may only be the latest targets of the American ‘strategic industrial policy’ state – market-leading technology companies that are to be crippled by political and regulatory means for the cardinal sin of enjoying a competitive advantage over their American counterparts in a cutting-edge strategic industrial technology or sector.

In the late-19th and early-20th century, the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Corporation of America, (also known as American Marconi), a subsidiary of the British giant, enjoyed a virtual lock on the U.S. radio equipment market. This was in large part due to its patent advantage. When the U.S. entered World War I in 1917, the government took control of most radio stations. Recognizing the strategic importance of radio equipment and wary of the threat of foreign control of U.S. telecommunications and radio systems, the Woodrow Wilson administration, led by the Navy Department, sought to ensure that an American company retained control of U.S. infrastructure for international wireless communication.

At the time, General Electric (GE) was the primary producer of the Alexanderson alternator, one of the first devices capable of producing the continuous radio waves needed to transmit signals across long distances, such as oceans. Seeking a monopoly on radio communications in the U.S. market, American Marconi opened negotiations with GE for exclusive rights to use the Alexanderson alternator. The U.S. government was opposed to any such agreement. Rather than ban or block the sale however, Washington appealed instead to GE’s patriotism and emphasized the dangers of allowing a foreign firm – even from a friendly country – to gain a monopoly over American communications infrastructure. GE bought into this line of argument and cancelled its contract with American Marconi. After the falling through of the sale, the U.S. government thereafter stared down British Marconi, American Marconi’s parent company, and compelled it to sell American Marconi to GE – thereby enabling GE to establish a radio monopoly. The name of this new GE subsidiary was the to-be-subsequently famous Radio Corporation of America (RCA).

The RCA case is a fitting one of how the U.S. government has taken advantage of its dominant regulatory power as well as close relationships between companies to produce desired outcomes. Facing the threat of being frozen out of the U.S. market, British Marconi was forced to make the only viable decision: cut its losses and sell its American stake to a U.S. business. And thereby enable a critical industry on American soil to be brought fully under U.S. control.

Source: “Building a Trusted ICT Supply Chain,” Cyberspace Solarium Commission, White Paper #4, October 2020

President Joe Biden’s ‘Build Back Better’ agenda has been likened by some to President Franklin Roosevelt’s ‘New Deal’. Both were forged at a time of record unemployment and economic despair. Both paid obeisance to the firm hand of an interventionist state. The ‘New Deal’ aimed to pull the U.S. out of the Great Depression through massive government programs; ‘Build Back Better’ aims to spend trillions of dollars to – quoting the President – “rebuild the backbone of the country” and “grow the economy from the bottom up and the middle out.” A number of competitiveness-related ‘industrial policy’ bills that are part-and-parcel of the “Build Back Better” agenda are currently awaiting congressional action. Key among them are the United States Innovation and Competition Act (USICA), the funding structure for the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) for America Act, and the Endless Frontier Act.

In addition to these pending legislative items, the Biden administration has also sought to deploy an Executive Branch-led ‘strategic industrial policy’ toolkit based on existing statutory authorities to steer the U.S. advanced manufacturing economy towards specific ‘new economy’ sectors. This policy toolkit features a mix of investment incentives, selective tariffs, tax credits, matching cost-share grants and loans, procurement preferences, and licensing of government-sponsored IP on easier terms, supplemented by additional support for basic and applied research. The following below is a (non-exhaustive) list of policy tools and lines of effort sought to be deployed by the Biden administration, as part of its “Supply Chain Resilience” plan.

Select U.S. industrial sectors, such as iron and steel, have long been the beneficiary of Buy American preferences, which aim to align domestic purchasing requirements with the long-term competitiveness, profitability and employment interests of that sector. That such preferences have done little to enhance competitiveness is another matter. These preferences stemming from a Depression-era law require all federally funded contracts to utilize domestic materials only. By way of a Reagan-era extension (Buy America) that specifically targeted mass-transit and rolling stock procurement, the end product/final manufactures benefiting from preferences also needs to be produced domestically. The Biden administration now proposes to extend this framework of procurement preferences to a list of “critical items and components,” and by doing so, reinforce the underlying supply chains for these critical items and components.

In late-July 2021, the Biden administration issued a Proposed Buy American Rule which, if implemented without revision, would constitute one of the most far-reaching changes to the implementation of the Buy American Act (BAA) since its inception almost 80 years ago. The Proposed Rule makes two notable changes to existing procurement rules. First, it raises the “domestic content test” – “domestic” means manufactured in the U.S.; and meets a specified percentage of domestic component parts determined by cost of the components – immediately from 55% to 60% and with an envisaged increase to 65% in 2024 and to 75% in 2029. For the time being, the Proposed Rule does not envisage the Federal Acquisition Regulatory Council replacing the “cost of components” test with a new “valued added” test. Had this been the case, it would have constituted a seismic change to BAA practices. The door to adopting a “value-added” test has nevertheless been kept ajar.

Second, and more crucially, the Proposed Rule outlines a framework that would allow for even higher preferences for domestic end products that are either on the government’s “critical items” list or contain domestically sourced “critical components.” Currently, the BAA encourages the use of domestic end products by imposing a price preference: large businesses offering domestic end items receive a 20% price preference, and small businesses receive a 30% price preference. Hence, if the preference factor in the new rule for a critical item is set at 5% and the lowest domestic offer for that critical item is from a large business, the government would be required to add a total of 25% to the price of the lowest non-domestic offer at the time of determining its contractual award. As to designating items as “critical”, this would be done separately via a quadrennial supply chain review, where the definition is expected to be further distilled as per criteria set by the White House’s Office of Management and Budget.

The underlying thinking of the Biden administration’s Proposed Rule is that by making ‘critical products’ eligible for preferences under the Buy American Act (BAA) and Federal Acquisition Regulatory Council rules, a stable source of federal government demand that could incentivize private sector investment in the production of these items will be established. In addition to the Biden administration’s Proposed Buy American Rule, major domestic procurement requirements for infrastructure materials are also included in the “Build America, Buy America” (BABA) provisions of the recently passed (November 2021) Infrastructure Investment and Job Act (IIJA) – better known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Deal. BABA bars the award of federal money to infrastructure projects unless all the iron and steel and related construction material used in the project are produced in the United States. And BABA extends the Buy America requirements, too, to non-ferrous construction materials used in manufacturing processes.

Aspiring Republican presidential candidates of an “America First” bent of mind have gone a step further, calling for the domestic sourcing principles of the Buy American Act to be applied to the entire commercial marketplace. All goods and inputs determined to be “critical for [U.S.] national security or essential for the protection of [the] U.S. industrial base” would become subject to local content requirements. If such goods are to be sold in America, they must be produced (above a threshold value) in America too, goes the thinking. It is not without a certain irony, then, that USTR’s National Estimates Report (NTE) of 2021 continues to denounce China for failing to delink its “indigenous innovation” policies from government procurement preferences – this, even as the U.S. government seems bent on extending federal procurement preferences to critical technology products and components.

Strengthening U.S. manufacturing commitments in federally funded grants, cooperative agreements and R&D contracts has been seen for some time as an important means to re-energize domestic manufacturing in critical or high value-added sectors. The Bayh-Dole Act of 1980 and its “exceptional circumstances” clause is viewed by the Biden administration as a useful tool in this regard.

The Patent and Trademark Law Amendments Act of 1980, better known as the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980, was one among several legislative initiatives introduced in the late-1970s and early-1980s to dispel concerns that U.S. industry was losing its competitive edge in global markets at a time of economy-wide productivity slowdown. Companion initiatives introduced at the time included the research and experimentation (R&E) tax credit in 1981 and the National Cooperative Research Act (NCRA) of 1984, which was amended in 1993 to become the National Cooperative Research and Production Act (NCRPA). The Bayh-Dole Act of 1980 loosened the conditions under which federal contractors that had acquired ownership of inventions created with federal funding could retain ownership of the invention’s underlying intellectual property. Prior to Bayh-Dole, federal procurement regulations required individuals, entities or their investors engaged in federally sponsored R&D contracts to assign the underlying patent rights of their inventions to the federal government (unless the funding agency determined that the public interest was better served by allowing the contractor or inventor to retain principal or exclusive rights). Bayh-Dole shifted this delicate patent rights-related balance in favor of the contractor/researcher, favoring in particular non-profit organizations, university research labs, and small business contractors. A second key change of Bayh-Dole was to authorize federal agencies to grant exclusive licenses to inventions owned by the federal government.

As an exception to the Act’s provisions, Bayh-Dole also contained an “exceptional circumstances” clause. As per this clause, the federal government enjoyed the power to exert greater ownership of intellectual property (IP) that is developed with federally-funded research, including by retaining title to the IP – so long as “exceptional circumstances” were present and doing so would better promote public interest objectives. This authority differs in respects from government march-in and royalty-free rights. At this time, an option under consideration by the Biden administration is to issue a “Determination of Exceptional Circumstances” under the Bayh-Dole Act and require that “Build Back Better” program grants, cooperative agreements and R&D contracts are tied to domestic manufacturing-related commitments by the awardee (i.e., the private inventor or contracting entity). Incentivizing domestic manufacture and expanding the impact of applications related to lithium batteries, the key power source behind items ranging from electric vehicles to smartphones, appears to be the objective for triggering Bayh-Dole’s “exceptional circumstances” clause. China is at this time the leader, far-and-away, in lithium chemical processing and battery production, and a core concern of U.S. policymakers is to locate a large-capacity battery supply chain domestically.

The Defense Production Act (DPA) of 1950 is a Cold War-era law that confers extraordinarily broad authority to the President to intervene economically as s/he feels fit in order to expedite and expand the supply of resources from the U.S. industrial base to support military, energy, and homeland security programs. Passed at the start of the Korean War and modeled on the WWII-era War Powers Act which gave President Roosevelt sweeping authority to control the economy during the wartime years, the currently amended version of the DPA affords the President exceptional authority to direct private companies to prioritize orders from the federal government, to allocate material, services and facilities for ‘national defense’ purposes, and to take actions to restrict hoarding of needed supplies. ‘National defense’ is defined broadly to include energy production and emergency preparedness activities.

Title III of the DPA authorizes the President to issue grants, loans, loan guarantees, and other economic incentives to establish industrial capacity, subsidize markets, and acquire materials to support the national defense. It also authorizes federal government procurement and installation of equipment in industrial facilities owned by the government or private persons. Title VII of the DPA authorizes the President to facilitate ‘voluntary cooperation agreements’ among private players, say for example among suppliers of critical materials, and thereafter grant relief to these participants from anti-trust laws. And by way of Section 705 (of Title VII), the President can also coercively obtain proprietary information from businesses “as necessary or appropriate for the administration of the DPA.”

The (threat of imposition of the) Defense Production Act of 1950 has already been utilized by the Biden Commerce Department to compel domestic and foreign semiconductor companies to provide detailed records, including proprietary information, linked to the ongoing shortages in the semiconductor product supply chain. Earlier, both Presidents Trump and Biden had resorted to the DPA to tackle the shortage of COVID-19-related critical medical supplies. At this time, the Biden administration’s purpose is not to utilize the DPA coercively but to explore investments rather in domestic strategic and critical material processing operations, especially rare earth elements, as well as incentivize downstream high value-added manufacturing such as new magnet capabilities and advanced electric motor designs. There is also a view that the DPA should be used to develop, mature, and scale proven R&D capacities and emerging technologies, particularly those developed by small businesses, and thereby assist in bridging the figurative “valley of death” from late-stage research to full-rate production. Additionally, Title VII authorities could be leveraged to convene industry representatives and approve ‘voluntary agreements and plans of action’ to better understand key technologies, components and materials requirements, and shortfalls, critical to U.S. military and industrial base needs.

Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 allows the President to impose import restrictions based on an investigation and affirmative determination by the Commerce Department that certain imports threaten to “impair the national security.” President Trump had notoriously imposed “textbook protectionist” Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum imports, citing the displacement of domestic production by excessive imports and the consequent adverse impact on the economic welfare of the industry, which in his view was undermining U.S. “national security.” This use of the ‘national security’ exception to restore the capacity utilization of the steel industry was at odds with the text of GATT Article XXI’s ‘security exceptions’, which requires that the action be “taken in time of war or other emergency in international relations” and should touch upon the member state’s “essential security interests.”

The urge to hijack this national security-linked tool to achieve industrial policy ends remains well-and-alive in the Biden administration – albeit, crafted on a much more selective basis. In September 2021, the Biden administration’s Commerce Department initiated its first Section 232 investigation to determine the effects on U.S. national security from imports of Neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) permanent magnets. Neodymium is a “light” rare earth element and neodymium magnets have wide-ranging defense and industrial applications. They are used in fighter aircrafts and missile systems but are also essential components of electric vehicles, wind turbines, computer hard drives, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) devices.

Neodymium magnets is also the example of a strategic and critical materials supply chain where only one country – China – is able to command vertical capabilities throughout the supply chain, whereas (multiple) other countries operate at only select tiers within the chain. Concentration of the supply chain in China notwithstanding, the U.S. Defense Department’s usage requirements amount to less than 5% of domestic consumption of rare earths. Reducing import dependence is primarily a matter of industrial policy, not one of national security. Furthermore, developing a domestic magnet value chain and reducing import dependency is better accomplished by rolling out a longer-term domestic transition plan and keeping market conditions predictable and undistorted. Providing subsidies/rebates on materials sourced from outside China and processed into magnets outside China could also encourage more non-Chinese production at each step of the supply chain. And it makes particularly little sense to impose unilateral – and potentially illegal – Section 232 tariffs and disadvantage downstream user, such as U.S. electric vehicle manufacturers, through higher input costs.

At this time, the Section 232 investigation of the effects on U.S. national security from imports of Neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) permanent magnets is in the post-comment review period. The Commerce Secretary has until June 2022 to present her department’s findings and recommendations to the White House. On the Hill meanwhile, a bill has been introduced to create a strategic reserve of rare earth elements and restrict the use of Chinese rare-earth metals in sensitive Defense Department systems.

Following the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-08, the Obama administration enacted a US$787 billion fiscal stimulus package – the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009. Among other provisions, ARRA introduced a tax credit for investments in manufacturing facilities for clean energy technologies and products, including energy storage systems for electric or hybrid vehicles. Potential recipients were evaluated using specified review criteria (including domestic job creation, impact on emissions, energy cost, etc.). Once selected, they were conferred a Manufacturing Tax Credit 48C certification and a credit amounting to 30% of qualified investment in advanced energy project property placed in service during a tax year, was applied. Totally, during ARRA’s implementation, the Section 48C tax credit was provided to 183 domestic clean energy manufacturing facilities valued at $2.3 billion. In addition to the tax credit program, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act also set aside US$2 billion to provide matching cost-share grants with industry to establish battery and electric drive manufacturing plants. Today, 31 of 38 manufacturing plants established through ARRA are still in operation.

– Authorizes funding for semiconductor R&D, including $3 billion for the National Science Foundation, $2 billion for the Department of Energy, and $2 billion for the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s (DARPA) Electronics Resurgence Initiative

– Creates a multi-agency National Semiconductor Technology Center that would conduct research and prototyping of advanced semiconductors in partnership with the private sector, with a recommended budget of $3 billion over ten years

– Establishes an Advanced Packaging National Manufacturing Institute under the Department of Commerce with a recommended budget of $5 billion over five years and creates a semiconductor program at National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) that would support a new Manufacturing USA Institute

– Creates a $10 billion trust fund to match state and local incentives for investments in semiconductor manufacturing facilities

– Provides tax credits for qualified semiconductor equipment or manufacturing facility expenditures through 2027

The Biden administration’s advanced manufacturing tax credit ambitions today are anything but modest, unlike the case with ARRA in 2009. The Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) for America Act is slated to provide a 40% refundable investment tax credit for qualified semiconductor equipment or any qualified semiconductor manufacturing facility investment expenditures through 2024. The credit scales down in 2025 and 2026 before phasing out in 2027. Totally, the tax credit is expected to run into the many billions. And similarly, on the on the matching cost-share front, there are views in the administration that a grant program should be established to support cell and pack manufacturing in the United States. Given that production of high-capacity battery cells in the U.S. is highly concentrated within a small number of companies, establishing such a grant program would lead to a diffusion of capabilities as well as create a number of high-value manufacturing jobs. The CHIPS Act also sets aside US$10 billion for a federal match program that matches state and local government incentives offered to a company that builds a foundry in that particular state or locality.

The scale of these subsidy sums also raises a vexing question: Don’t such excessively large subsidy sums distort trade and investment markets? Samsung is expected to benefit to the tune of US$7.5 billion in federal and local incentives relative to its total investment of US$16.7 billion in a microchip plant in Taylor, Texas. The Kishida government in Japan is in the process of drawing up a bespoke law to subsize Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC) chip plant in Kumamoto prefecture to the likely tune of US$ 3.5 billion – estimated to be half the cost of building the new plant. And the European Commission has signaled that it will relax its strict state aid and anti-subsidy regime to accommodate European Chips Act-related investments in large, cross-border semiconductor projects that qualify as Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEI). Don’t these large subsidy intervention rates (almost 40-50% of project cost) distort the international marketplace? And at a time when trade ministers of the U.S., EU and Japan have sought to proscribe “excessively large [Chinese state] subsidies” because of their “serious negative trade or capacity effects,” are they not undercutting their own plurilateral rulemaking on industrial subsidies by dispensing these liberal corporate handouts?

The Biden administration’s “Build Back Better” agenda and “Supply Chain Resilience” plan constitute one of the most ambitious and interventionist efforts to forge economy-wide ‘industrial policy’ outcomes since the end of the Second World War. In addition to the various authorities discussed above, the administration has also thrown its weight behind a federal program to provide ‘point-of-sales’ consumer rebates for purchases of electric vehicles (EV) containing high U.S domestic content. Providing a (consumer-facing) tax credit that is dependent on the assembly of the vehicle in the U.S. as well as on the unionization status of the plant assembling the car would amount to a violation of USMCA (United States, Mexico, Canada Agreement) and WTO rules, respectively. This has been conveyed to the Biden administration by its international partners but is unlikely to force a change of heart, given the administration’s imperative to carry the Rust Belt states – where these EVs are to be assembled – in congressional and presidential elections. More broadly, the success of the Biden administration’s ‘strategic industrial policy’ project remains to be seen. Time will tell whether the ambitious effort has been effective in pivoting the U.S. manufacturing economy towards achieving successes in the key advanced technology-enabled sectors that underpin the Fourth Industrial Revolution, as well as in bending the curve of the economy-wide productivity decline that has been evident for some time now.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2025 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

The U.S. Auto Industry Has Not Lost Yet—But It Must Compete Smarter