The buildings located on the Red Square: Kremlin wall (at left) and Saint Basil’s Cathedral (at right), Moscow, Russia. UNESCO World Heritage Site. (Source: Getty Images, Royalty-Free)

Resident Senior Fellow &

Head, Trade 'n Technology Program

The United States and the West have executed an economic, financial, and technology sanctions blitzkrieg against Moscow that has few parallels in terms of speed and scale. The degree of Russia’s ability to adapt and substitute for the loss of economic, financial, and technology access will ultimately determine the costs of the imposed sanctions regime.

Four types of financial sanctions—property blocking sanctions; non-property blocking debt and transaction sanctions; specialized financial messaging services-related restrictions; and measures targeting the Russian Central Bank—have been imposed on three sets of Russian actors—state-owned and private banks and other financial institutions; select individuals and non-financial corporate entities; and on economy-facing state bodies. Of the four, the ace-in-the-hole has been the early and coordinated measure by the West to target the hard currency reserves of the Central Bank of the Russian Federation (RCB). There is still headroom for more financial sanctions.

A slew of new Russia-related licensing policies and license requirements have been introduced on the export controls front. Among the new requirements introduced, the two new sections of the Foreign-Produced Direct Product (FDP) Rule that is specific to Russia and to Russian ‘military users’ are the ace-in-the-hole. The two sections constitute the first instance when the FDP rule has been applied to a whole country; previously, the FDP rule had been applied to individual entities, such as Huawei. Together, these two sections are expected to substantially limit the availability of key microeconomic parts and components and degrade Russia’s technological base.

On the trade policy front, Russia has been stripped of its Most Favored Nation (MFN) status and subjected to a number of product import bans. However, until an energy embargo is imposed, the trade measures will remain more or less inconsequential. Additional measures that have been imposed include visa restrictions, national airspace and port entry bans, sanctions on Russian state-linked broadcasters, etc.

China must equip itself with the capability to deny an adversary the means to dominate the chokepoints of the global economy’s infrastructural plumbing to its detriment. Aside from a few tailored instances, this will counterintuitively require more, not less, globalized trade integration; more, not less, domestic and international financial deepening; and more, not less, engagement within cross-border technology ecosystems on Beijing’s part.

Two months on, Ukraine has not folded in the face of Russia’s supposed military blitzkrieg. On the other hand, the United States and the West have executed an economic, financial, and technology blitzkrieg against Moscow with few parallels in terms of speed and scale. The Central Bank of the Russian Federation has been prevented from deploying its hard currency reserves, major Russian banks have been removed from the SWIFT global financial network, stringent technology controls have been imposed, ‘most favored nation’ trade privileges have been withdrawn, the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline has been de-operationalized, energy import bans are being put in place, Western airspaces and ports have been closed to Russian aircraft and vessels, and President Putin and numerous high-ranking officials and wealthy businessmen have had their overseas assets frozen. As a result, the Russian Central Bank has had to hike interest rates and impose capital controls, Russian equities have been removed from global indexes, multinational firms have exited the market, the defense industrial base is being degraded of important microelectronic parts, the country is staring at its first foreign debt default since the Bolshevik Revolution, and the country more broadly is looking at longer-term socioeconomic losses that could tally in the tens if not hundreds of billions of dollars. Even once the sanctions are loosened, experience suggests Western banks and corporations will be slow to return, fearing a reputational backlash.

The United States and the West’s recourse to economic and financial warfare are not unprecedented. Historically, great powers have sought to economically kneecap their adversaries using a combination of food, oil, or credit sanctions. In the early-19th century, blockades and the destruction of supplies deemed essential to an adversary’s war economy were the weapons of choice. A hundred years later, Great Britain translated its dominance of the infrastructure of the global trading system – financial services, insurance and reinsurance, shipping, telecommunications – to deny Wilhelmine German access to this infrastructure once war broke out. Likewise, today, Washington and the West have seized control of the centralized chokepoints of the 21st century’s global economic and financial networks to asphyxiate the Russian economy. What is unprecedented about the West’s economic assault this time though is that it is not a directly involved belligerent; Moscow and Kyiv are the parties to the conflict, and Moscow, furthermore, is America’s UN Security Council peer.

The degree of Russia’s ability to adapt and substitute for the loss of economic, financial, and technology access will ultimately determine the costs of the imposed sanctions regime. As the clandestine proxy networks that have enabled Iran’s ‘resistance economy’ to end-run sanctions or as the ruble’s bounceback in value testify, the cost may turn out to be far lower than advertised. Be that as it may, the sanctions regime offers a handy playbook – a proof of concept – of how economic warfare is prosecuted in the 21st century. What are its key nodes and chokepoints? What are the instruments of punishment and levers of control? Just as importantly, where are the carveouts in the sanctions regime and what do they signify for future targets of Western sanctions? And, finally, in the age of 21st-century economic warfare, where does one draw the line at which point a state is deemed ‘too big to fail’—as in, it is too systemically important and too financially and technologically interconnected within the global economy and capable as well of inflicting its own ‘economic balance of terror’ to be unilaterally sanctioned? What must China do to get to and graduate beyond this point?

The United States and the European Union have imposed wave-upon-wave of targeted sanctions and restrictions against Russia for its ongoing invasion of Ukraine that started on February 24th. The measures build on the December 2014 ‘Crimea’ sanctions, the April 2021 ‘Navalny’ sanctions, and the February 22, 2022 sanctions imposed on Moscow for its recognition of the independent status of the (Ukrainian) Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics. The U.S. and EU measures target a wide swathe of economic activity in a number of critical sectors (finance, aerospace, microelectronics, advanced technologies, defense, etc.). They primarily fall into three categories – financial sanctions, export controls and investment bans, and revocation of trade privileges and import bans.

Four types of financial sanctions–property blocking sanctions; non-property blocking debt and transaction sanctions; specialized financial messaging services-related restrictions; and measures targeting the Russian Central Bank–have been imposed on three sets of Russian actors–state-owned and private banks and other financial institutions; select individuals and non-financial corporate entities; and on economy-facing state ministries and bodies.

Of the four types of financial sanctions, the ace-in-the-hole has been the early and coordinated measure by the West to target the hard currency reserves of the Central Bank of the Russian Federation (RCB). On February 26, 2022, the United States and European Commission introduced restrictions on transactions with the RCB related to the latter’s management of its reserves and assets with a view to preventing the RCB from deploying them to undermine the impact of sanctions. The prohibition was clarified in late March to include the Bank’s (as well as the Russian Finance Ministry and National Wealth Fund) gold reserves too. U.S. nationals are also prohibited from supplying U.S. dollar-denominated banknotes to the Russian government or to persons based in Russia. Following revelations in early April of a massacre in the Ukrainian town of Bucha, the U.S. Treasury has prohibited the RCB from making coupon payments on its foreign currency-denominated sovereign debt too utilizing funds parked in the latter’s account at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY).

As a result of these measures, Russia is staring potentially at its first foreign debt default since the Bolshevik Revolution. The RCB has also had to impose capital controls and hike interest rates, and the stability of its domestic financial sector is not assured. Hard currency reserves are, after all, not just a tool of exchange rate and monetary policy management. They also serve a lender of last resort function to streamline foreign currency maturity and liquidity mismatches faced by domestic financial and non-financial corporate enterprises during a crisis.

The U.S.’ ‘shock and awe’ central bank sanctions are not entirely unprecedented. Presidents have frozen foreign state assets under U.S. jurisdiction, including central bank reserves, as a bargaining tool during foreign policy (Iran, 1979) and non-proliferation (Iran, 2019) crises, as well as channeled frozen state funds to U.S.-recognized opposition governments (such as Panama’s Delvalle government, 1988; Venezuela’s Guido government, 2019). In a troubling recent case, the Trump administration even threatened to freeze the Iraqi central bank’s access to its FRBNY-held funds if the central government in Baghdad proceeded on the legislature’s motion to expel U.S. troops from its territory – this, after Washington had assassinated a senior Iranian general on Iraqi soil. That said, the imposition of central bank sanctions against a UN Security Council Permanent Five (P-5) peer is without precedent. At this time, the Russian Central Bank is pursuing legal avenues to recover its $300 billion-plus of frozen reserves. And as a countermeasure to backstop the ruble’s value in currency markets, Moscow has also insisted that all foreign gas buyers from “unfriendly countries” open parallel ruble and foreign currency accounts with Gazprombank, the designated payment institution, in order to exchange currency for rubles to make their gas purchase payments. Poland and Bulgaria have even had their gas supplies suspended for failure to comply with Moscow’s revised payment terms.

Beyond the measures targeting the Russian Central Bank’s reserve management and other foreign exchange operations, the Biden administration has imposed three other types of financial sanctions. By ascending order of severity, the least onerous are restrictions on providing correspondent banking services to designated Russian banks and debt and equity transaction restrictions with designated Russian banks and corporate entities. The sanctions were announced on the day of the invasion by the Treasury Department and also targeted entities in a range of critical non-financial sectors, such as transportation, mining, and oil and gas production and distribution. Some of these designated entities have been slapped with progressively upgraded sanctions as the war has dragged on. For example, Sberbank, Russia’s largest bank accounting for approximately 60% of household deposits, and Alrosa, the world’s largest diamond mining company accounting for 28 percent of global diamond mining, were upgraded from the debt and equity transactions list to the property blocking category (on property blocking sanctions, see Box 1) on April 7, 2022.

The U.S. dollar accounts for a significant share of cross-border liquidity, funding, invoicing, and settlement and payments, and punches well above America’s economic heft in the global economy. Its strength in the international monetary and financial system derives from a combination of two peerless attributes: the size, depth and liquidity of the U.S. Treasury bond market, and its full openness and convertibility on the capital account. For reasons of market fragmentation, the euro and Europe are unable to replicate the former; the renminbi and China, for reasons of domestic financial market underdevelopment, are still more than a decade away, at minimum, from instituting the latter.

Financial sanctions that leverage the dollar’s indispensable role at the heart of the international monetary order, and especially its payments system, have been the workhorse of the U.S. sanctions regime since the mid-2000s. The net cast is extraordinarily wide. Per regulations issued by OFAC (Office of Foreign Assets Control), the relevant administering body in the U.S. Treasury Department, any U.S. dollar-denominated transaction that is processed through the U.S. clearing and settlement system falls within the purview of U.S. sanctions policy. As such, even an offshore transaction that does not engage an American person but involves a sanctioned foreign party and is conducted in U.S. dollars amounts to a violation of the sanctions regime, given that OFAC enjoys jurisdictional nexus over offshore dollar clearing systems – be it in Hong Kong, Singapore or elsewhere. The relevant clearing banks within Singapore’s U.S. Dollar Cheque Clearing System (USDCCS) or Hong Kong’s Clearing House Automated Transfer System (CHATS) are American entities and are hence subject to U.S. jurisdiction.

OFAC’s extraordinary power derives from Section 203 of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), which authorizes the President, once s/he has declared a national emergency, to investigate, regulate, or prohibit:

(i) any transactions in foreign exchange,

(ii) transfers of credit or payments between, by, through, or to any banking institution, to the extent that such transfers or payments involve any interest of any foreign country or a national thereof,

(iii) the importing or exporting of currency or securities,

by any person, or with respect to any property, subject to the jurisdiction of the United States;

By way of Section 203(1)(B), IEEPA also grants the President the authority to:

investigate, block during the pendency of an investigation, regulate, direct and compel, nullify, void, prevent or prohibit, any acquisition, holding, withholding, use, transfer, withdrawal, transportation, importation or exportation of, or dealing in, or exercising any right, power, or privilege with respect to, or transactions involving, any property in which any foreign country or a national thereof has any interest by any person, or with respect to any property, subject to the jurisdiction of the United States;

OFAC’s property-blocking sanction, essentially the authority to freeze dollar-based assets, derives from this provision of IEEPA. As per OFAC’s 50% rule, issued initially in February 2008 and revised thereafter, U.S. nationals are broadly prohibited from transacting with entities/persons that are placed on the ‘SDN List’ (List of Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons) or are owned in a 50% or greater intensity by SDNs and Blocked Persons, individually or in the aggregate, directly or indirectly. As such, the property of SDN’s who enjoy 50% or more ownership control and which fall within U.S. jurisdiction is ‘blocked’ or frozen. Non-U.S.-parties are liable to be slapped with ‘secondary sanctions’ too if found to be transacting with an SDNs/Blocked Person, given the extension of OFAC’s authority over all dollar-denominated clearing and settlement activity worldwide. As fearsome as OFAC’s 50% rule might appear, it is not without its detractors. The chief criticism levied is that sanctioned entities typically evade the 50% threshold – and thereby the full brunt of the sanction – by employing beneficial ownership structures via shell companies and proxies and utilizing interlocking minority ownership interests to exercise control.

The origins of the president’s broad authority under IEEPA date back to the First World War-era Trading With The Enemy Act (TWEA), which conferred expansive control over private international transactions during wartime to the presidency. As per Section 5(b) of TWEA, the president may “… investigate, regulate, or prohibit … any transactions in foreign exchange, export or earmarking of gold or silver coin or bullion or currency, transfers of credit in any form … or of the ownership of property between the United States and any foreign country … or between residents of one or more foreign countries …” During the Great Depression, Section 5(b) was amended to make it applicable also to national emergencies other than war. And during the Second World War, TWEA was amended again to “vest” the president with the authority to permanently seize and liquidate property subject to the U.S.’ jurisdiction in which a foreign enemy government or national may have an interest.

Today, the IEEPA, as amended, confers on the president the authority to “confiscate any property … of any foreign person, foreign organization, or foreign country that he determines has planned, authorized, aided, or engaged in [armed] hostilities or attacks against the United States.” Until the Biden administration’s seizure and liquidation of $7 billion of U.S.-based assets belonging to Da Afghanistan Bank, Afghanistan’s central bank, earlier this year, the only prior instance of the employment of this “vesting power” occurred in March 2003 when President George W. Bush ordered the blocked property of the Iraqi government and its agencies to be vested in the Treasury Department and be used to assist the Iraqi people. The vested assets were used for reconstruction purposes as well as to cover the operations cost of the Coalition Provisional Authority.

Next, in ascending order of severity, have been rolling waves of property blocking sanctions imposed on an ever-expanding roster of individuals and entities that have been dumped into the Treasury Department’s List of Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (SDN List). On February 24, 2022, the earliest designees were Sergei Ivanov and Nikolai Patrushev, two of President Putin’s closest allies, the CEOs of Alrosa, Rosneft, and Nord Stream 2 AG, as well as VTB, Russia’s second-largest bank. The SDN List has since been expanded to include President Putin himself, former President Medvedev, Prime Minister Mishustin, Foreign Minister Lavrov, Defense Minister Shoigu, Armed Forces Chief of Staff Gen. Gerasimov, 21 members of the State Security Council, 328 Duma members, and a host of prominent bankers, industrialists, and oligarchs, among others. Some family members of top officials, too, have been listed for added measure.

As to the entities listed, these include numerous large defense sector firms, including United Shipbuilding Corp., Russia’s largest naval shipbuilder, diamond mining giant, Alrosa, and the largest state-controlled (Sberbank) and privately-owned (Alfa-Bank) banks. With the designation of the latter two banks, three of the four largest financial institutions accounting for three-fifths of the sector’s assets are now on the SDN List. Notably missing from the list due to its role as a payment processor for the natural gas trade with the European Union is government-controlled Gazprombank. This is not an unfamiliar role. Following the Russian financial crisis of 1998, when the government defaulted on its domestic debt obligations, Gazprombank took over most of the gas export contracts and became a key dealer of foreign currencies. However, this could change with the European Union looking to institute an embargo on Russian energy imports.

Property-blocking sanctions, essentially the authority to freeze assets, derive from Section 203 of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA). It applies to transactions conducted in traditional or virtual currency. It is also easily implementable. Freezing dollar-denominated banking sector assets or seizing yachts and luxury properties of oligarchs does not require the government to show proof of a specific violation of the law. An assertion of wrongdoing is sufficient. On the other hand, liquidating these assets is easier said than done. The constitution’s Fifth Amendment’s guarantee against government seizure of private property “without due process of law” as well as the protections afforded against the “taking” of property without “just compensation” require that evidence of criminality tied to the seized asset be proven in a court of law. This is a difficult threshold to surmount. At this time, the Biden administration is examining new legislative authorities that would allow for a less-unwieldy forfeiture process linked to Russian kleptocracy.

The U.S. and EU’s financial sanctions have evoked ‘shock and awe’ within the international monetary and financial system. There is much room still to scale them upwards, nonetheless.

First, more banks, including prominent ones such as Sberbank and Alfa-Bank, and down-the-line even Gazprombank, can be removed from the SWIFT messaging service network, thereby disconnecting the Russian banking system from the Western-led global financial system.

Next, additional banks could be designated as a “primary money-laundering concern” as per Section 311 of the USA Patriot Act. Akin to a SWIFT eviction, the designation would paralyze their access to the global financial system. It bears noting parenthetically that the U.S. has itself been tagged as a money laundering destination on four counts in the Financial Action Task Force’s (FATF) most recent country review.

Third, a much wider range of Russian non-financial corporate enterprises could just as easily be designated on the Treasury’s SDN list and subjected to property blocking sanctions. The range of industrial sectors subject to property blocking by the U.S. is narrow and pales in comparison to the EU’s range of sectoral designees.

Fourth, the Russian energy sector carveout could be incrementally rescinded. Companies such as Rosneft, Transneft, and Gazprom could be subjected to property blocking, and tanker fleets carrying Russian oil denied hull and machinery insurance (covering physical damage to vessels) and protection and indemnity insurance (covering third party liability, such as pollution or collision). The former is typically purchased via Lloyd’s of London marine and aviation syndicates, and 80% of P&I contracts too are written in London. International classification societies that certify the safety and seaworthiness of Russian-operated tankers and bulk carriers have already pulled out of the country. In the case of Iranian oil, the threat of secondary sanctions was also wielded, and purchasing countries were told to maintain their tapered-down oil payments in an escrow account under their jurisdiction.

Finally, the Biden administration could label the Russian government as a “State Sponsor of Terrorism” in order to ‘vest’ state assets to pay Ukrainian claimholders filing suit in U.S. courts under the Alien Tort Statute’s principle of universal jurisdiction. This would admittedly, be a stretch of the existing statute.

The severest financial sanctions so far, which are confined to a handful of Russian financial institutions, have been their expulsion from the specialized SWIFT (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication) financial messaging service network. When paired with a property blocking sanction, the measure effectively amounts to an eviction from global financial networks. Workarounds, such as utilizing bilateral messaging systems or China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS), which is still in its infancy and processes less than 1% of SWIFT’s transaction volume, is not a realistically scalable option; it is at best a niche one for, say, routing Russian-held funds to the United Arab Emirates using the offshore Chinese yuan. The seven Russian banks expelled by the European Union (SWIFT is headquartered in Belgium and falls under EU jurisdiction) are: VTB, Bank Otkritie, Novikombank, Promsvyazbank, Bank Rossiya, Sovcombank, and VEB. The expulsion came into effect on March 12, 2022.

The export controls and technology denials imposed on Putin’s Russia by-and-large fall into three categories: expanded export licensing requirements applicable to many dual use items; expansion of the ‘foreign direct product rule’ to deny access to goods or components, wherever manufactured, that contain controlled U.S.-origin technology or software; and expansion of control vis-à-vis Russian military end users to effectively cover all U.S.-origin goods.

On February 24, 2022, in conjunction with the various Treasury Department-enforced financial sanctions, the U.S. Commerce Department issued a Final Rule that introduced a slew of new Russia-related licensing policies and license requirements. These requirements build on the existing export control measures targeted at Russia while imposing significant new depth and complexity.

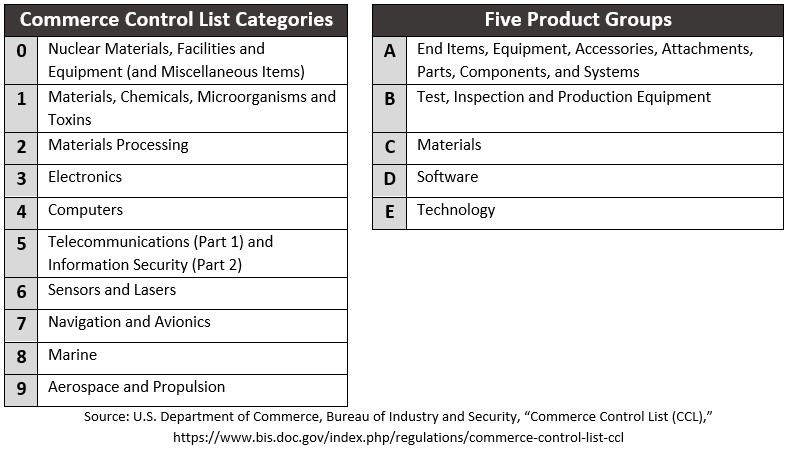

First, the new rule imposes a new Commerce Control List (CCL)-based license requirement for U.S.-made items exported or transferred to Russia. Specifically, license requirements were added for all ECCNs (Export Control Classification Numbers) in categories 3-9 of the Export Administration Act’s (EAR) Commerce Control List (CCL). Some of these items, including certain microelectronics, telecommunications items, sensors, navigation equipment, avionics, marine equipment, and aircraft components, were not previously controlled with regard to Russia. Post-April 8, all categories of items on the Commerce Control List, including those in categories 0-2, now require a license for export or transfer to Russia. As a result of these new requirements, foreign-produced items that are exported to Russia and incorporate more than a 25% de minimis level of ‘controlled’ U.S.-origin content are also subject to controls. Going forward, Russia could yet be downgraded to the EAR’s Country Group E (joining Cuba, Syria, Iran, and North Korea), to whom a 10% de minimis threshold applies.

Next, the new rule applies a more stringent review policy to license applications for Russia-destined exports or transfers. License applications will now be reviewed under a policy of denial. For certain limited exceptions, a case-by-case review process will apply – these exceptions are related to the safety of flight, maritime safety, civil nuclear safety, humanitarian needs, civil telecommunications infrastructure, and government-to-government activities, including government space cooperation. NASA’s joint operation of the International Space Station is currently dependent on its Russian counterpart for re-boosting when the station needs to move into a higher, safer orbit. Other general exceptions that continue to be available are: temporary imports and exports for items for use by news media; software updates for civil end-users in Russia that are subsidiaries or joint ventures of U.S. companies or companies of allied countries; and encryption items and certain communication devices (CCD) and software for use by independent non-governmental organizations and individuals in Russia, ostensibly to subvert government information controls. Both Google and Apple’s app stores remain accessible in Russia. The CCD exception was previously applicable to only Cuba.

Third, the new rule expands the scope of the ‘military end users’ and ‘military end uses’ restrictions on Russia. In December 2020, the Trump administration had created a new ‘Military End User’ (MEU) List, which in addition to Russia, currently includes Myanmar, Cambodia, China, and Venezuela. The new rule substantially restricts all Russia-destined items and transfers the first tranche of 45 existing Russian entities listed on the MEU List to the Entity List, where the level of controls is qualitatively stricter.

Fourth, the new rule creates two new sections of the Foreign-Produced Direct Product (FDP) Rule that is specific to Russia and Russian ‘military users’. Akin to the unanticipated financial sanctions measure targeting the Russian Central Bank’s hard currency reserves, these two new Russia-specific sections are the ace-in-the-hole on the export controls front insofar as the Russia sanctions are concerned. These new sections constitute the first instance when the FDP rule has been applied to a whole country and not just to selective entities falling under that country’s jurisdiction, such as was the case with Huawei (see Box 3). Together, they are expected to substantially limit the availability of key microeconomic parts and components and degrade Russia’s technological base over the short and medium-term.

The first section creates a new ‘Russia Foreign Direct Product Rule’ (Russia FDP Rule) which establishes U.S. export controls jurisdiction over foreign-produced items when they are bound for Russia or a Russian end-user, and is: (i) the direct product of certain U.S.-origin software or technology subject to the EAR; or (ii) produced by certain plants or major components thereof which are themselves the direct product of certain U.S.-origin software or technology subject to the EAR. The ‘Russia FDP Rule’ essentially applies when it is known that a software or technology item produced outside the United States but containing U.S.-origin inputs is destined to Russia or will be incorporated into or used in the production or development of any part, component, or equipment produced in or destined to Russia. The software (ECCN product group D) and technology (ECCN product group E) items covered under this rule are expansive but do not apply to low-technology consumer goods. As a matter of background, the Commerce Control List (CCL) is divided into ten broad categories of items, which are each further sub-divided into five product groups from A-E.

Much like the U.S. Treasury Department wields its List of Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (SDN List) to fearsome effect, the U.S. Commerce Department’s weapon of choice is the Entity List. Licensing, and prohibitions under the Entity List, fall into three categories by degree.

First, are generalized controls on all commodities, software, and technology subject to U.S. jurisdiction under the Export Administration Act (EAR) – i.e., produced in the U.S. or exported from the U.S. – that are destined to designees listed in the Entity List.

Next, are controls on commodities, software, and technology that are not U.S. produced but nevertheless contain de minimis amount of U.S. content that are subject to the EAR. For such non-U.S. produced items containing de minimis U.S. content and are destined to listed designees in China, licensing is required if the controlled U.S.-origin content exceeds a 25% de minimis amount. For non-U.S.-produced encryption technology that incorporates controlled U.S.-origin encryption and Munitions List items, there is effectively no de minimis level.

Finally, there are controls on commodities, software, and technology that are not U.S. produced and contain less than de minimis controlled U.S.-origin content but meets the criteria of being a “direct product” of certain sensitive U.S. technology or software. Items produced at a non-U.S. manufacturing plant also fall within the ambit of this ‘foreign direct product’ (FDP) rule if the plant or plant component is a product of certain sensitive U.S. technology or software. The reach of the FDP rule’s application is evidently extensive.

All three dimensions came to the fore during the Trump administration’s sanctioning of the Chinese technology firm, Huawei. On May 16, 2019, the Commerce Department added Huawei Technologies and 68 of its non-U.S. affiliates to the Entity List, claiming reasonable suspicion of U.S. national security breaches. In reality, the placement in the Entity List was intended to cut off the company’s access to U.S. designed chips as well as U.S. design tools destined for its chip design subsidiary, HiSilicon, and thereby thwart Huawei’s leadership position in the global 5G telecoms equipment market.

Failing to materially choke Huawei’s access to sophisticated (Taiwanese) chips fabricated with U.S. chip-making tools, the ‘foreign direct product’ rule was amended on May 19, 2020, to extend it to non-U.S. items when those items are (1) produced using certain equipment that is the “direct product” of specified U.S.-origin technology or software and destined for Huawei and (2) the “direct product” of technology or software produced or developed by Huawei.

On August 17, 2020, the regulation was further clarified to specify that transfers were effectively prohibited for any foreign-produced item that contained the “direct product” of specified U.S.-origin technology or software when that foreign-produced item was to be “incorporated into … the ‘production’ or ‘development’ of any ‘part,’ ‘component,’ or ‘equipment’ produced, purchased, or ordered by [Huawei] or [when Huawei was] a party to any transaction involving the foreign-produced item, e.g., as a ‘purchaser,’ ‘intermediate consignee,’ ‘ultimate consignee,’ or ‘end-user.” All doors to cutting-edge chips, chip design or chip production equipment were slammed shut. However, to keep space open for sales of systems, equipment, and devices at a lower level of technological sophistication to Huawei, the regulation clarified that license applications for foreign-produced items below the 5G level (e.g., 4G, 3G) would be reviewed on a case-by-case basis. In December 2020, additional guidance was posted regarding the Commerce Department’s interpretation of the August 2020 Foreign Produced Direct Product Rule.

The second section of the Russia-specific rule creates a new ‘Russia Military End-User Foreign Direct Product Rule’ (Russia-MEU FDP Rule) that is even more stringent in its application. It applies specifically to all ‘military end users’ designated in Footnote 3 of the EAR’s Entity List. Under the Russia-MEU FDP Rule, all license applications related to foreign-produced items that are: (i) the direct product of any software or technology subject to the EAR; or (ii) produced by certain plants or major components thereof which are themselves the direct product of any U.S.-origin software or technology subject to the EAR, are to be reviewed under a policy of denial with minimum-to-no exceptions available. Since the conflict began in late February, almost 150 Russian ‘military end users’ across the aerospace, maritime, and defense sectors have been designated in Footnote 3 of the Entity List, severely limiting the universe of commodities, software, and technologies obtainable to them, going forward, in the global marketplace.

The Russia-MEU FDP Rule begs the question, though, as to how this section of the regulation is to be enforced, given that the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS), the relevant administering body in the Commerce Department, no longer has export control officers on the ground in Russia and just two in China to conduct end-use related verification checks. The Russia-MEU FDP rule complements the EU’s Annex VII list of export-controlled goods that could contribute to Russia’s military and technological enhancement. The list is broad, ranging from semiconductors, encryption equipment, navigation, avionics, aerospace equipment, sensors and lasers, and vehicle engines and propulsion equipment.

Following the initial batch of export controls imposed in late February, additional controls have been imposed on Russia’s oil refinery sector and on the supply of luxury goods to oligarchs listed on the Treasury Department’s SDN List as well as to any person based in Russia. Enforcement action (Temporary Denial Orders) has also been taken against three Russian passenger airlines and one Russian cargo airline for operating aircraft in violation of U.S. export controls. Meanwhile, 37 partner countries that have implemented substantially similar export controls under their domestic laws have since received full or partial exclusions from the FDP and de minimis rules’ license requirements pertaining to ‘controlled’ U.S.-content. Asian members of this Global Export Controls Coalition are Japan and South Korea.

Starting early March 2022, the United States and allied and partner governments have also begun to institute outbound investment bans with respect to Russia. On March 8, President Biden issued an Executive Order prohibiting “new investment in the energy sector in the Russian Federation by a United States person, wherever located …” Following the revelation of a massacre in the town of Bucha, leaders of the G7 countries resolved in early-April to ban all “new investment in key sectors” as well as “specific services” essential to Russia’s economy. Per a follow-up Executive Order, the Treasury Secretary enjoys the authority to prohibit “any category of services as may be determined by [her],” which could range from credit ratings services to provision of accounting, trust, and corporate formation, and management consulting services to Russian companies and wealthy elites. On the other hand, the U.S. Treasury Department has also issued guidance clarifying that the prohibition on new investment in the energy sector does not apply to the provision of goods or services with respect to pre-existing energy projects in Russia.

At a time when over 750 Western companies have left Russia, voluntarily or otherwise, it goes without saying that none are contemplating new investments in the country. Experience suggests that even once the sanctions are loosened, Western companies will be extremely slow to return, fearing reputational backlash. And in any case, no insurer or reinsurer will write political risk cover for new investments at this time.

Russia has been a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) since 2012. Membership entitles it to enjoy the most favored nation (MFN) privilege as per which WTO members are required to extend the same tariff terms to fellow WTO members, with certain exceptions such as preferential trade arrangements. (To be clear, though, in the U.S. customs area, Moscow has effectively enjoyed MFN level tariffs via U.S. presidential waiver authority ever since the coming into effect of the United States-Russia Bilateral Commercial Agreement of June 1992.) That said, during a “time of war or other emergency in international relations”, member states enjoy the latitude to invoke the GATT Article XXI Security Exception and take “any action it considers necessary for the protection of its essential security interests,” including revocation of the MFN privilege. Typically, parties directly involved in a conflict may avail of this security exception. During the Cold War, however, non-combatant member states did not hesitate to invoke the exception for (non-military) political reasons. For example, during the Falkland Islands War of 1982, the European Community, Canada, and Australia invoked GATT Article XXI and suspended imports from Argentina. To this day, Washington justifies its trade embargo against Cuba using this same article.

On March 15, 2022, the United States, the European Union, and 12 member states, including Japan and South Korea, notified the WTO General Council in a joint communication of their intent, individually, to invoke the national security exception and “take any actions … necessary to protect our essential security interests … [including] actions to suspend concessions or other obligations … such as the suspension of most-favored-nation treatment to products and services” of Russia. No developing country or emerging market economy was represented in this group. Three weeks later, on April 7, President Biden signed into law H.R. 7108, the “Suspending Normal Trade Relations with Russia and Belarus Act”, which strips Moscow of its MFN trade status. H.R. 7108 passed the House by 420 votes to 3 and the Senate unanimously (100-0). Hill action was essential given that the right to regulate foreign commerce rests constitutionally with Congress and not with the executive branch.

As to its real-world implications, the United States Trade Representative’s (USTR) availing of the GATT Article XXI security exception and Congress’ stripping of Russia’s MFN status amounts to (much) less than the headline effect. While the gap in the U.S.’ tariff schedule between the applied MFN rate and the average rate applicable overall to Russia is large – analysts place the difference at approximately 30% – the effect on many of the (few) key tariff lines that constitute a significant chunk of Moscow’s exports to the U.S. is practically nil. Be it urea used as fertilizer, palladium used in catalytic converters and semiconductors (a single Russian mining company, Norilsk Nickel, is responsible for almost 40% of the world’s annual palladium production), or U235 enriched uranium to generate nuclear electric power, these items are currently subject to a 0% tariff rate and will continue to enter the U.S. duty-free regardless. Besides, other vital exports from Russia, such as steel and aluminum, have already been elbowed out of the U.S. market via antidumping and countervailing duty actions. In addition to the tariff measures, the Biden administration has also imposed a ban on the importation of Russian-origin fish, seafood, alcoholic beverages, and non-industrial diamonds. As noted earlier, the administration had also issued an Executive Order banning the importation of Russian origin-energy products (the same EO instituted a ban on new investments in Moscow’s energy sector too).

FIGURE 1: U.S. Utility Purchases of Uranium Products from Russia, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan (2014-2018)

The energy product ban, and more specifically its carveouts, is as revealing in as much in what it conceals – much like the case of the more-or-less inconsequential stripping of Russia’s MFN rights. The ban extends to crude oil, petroleum, petroleum fuels, oils and products of their distillation, liquified natural gas, and coal and coal products. The United States is a marginal importer of these energy products, unlike Europe or, for the matter, Japan. On the other hand, the energy products not subject to the import ban include uranium, wood, and agricultural products used to produce biofuels. And for good reason. The nation’s 98 nuclear power generating reactors, which supply 19% of U.S. electricity consumption, are dependent on uranium imports from Russia (and the two ex-Soviet states) to maintain normal operations at their reactor complexes. Between 2014 and 2018, U.S. utilities relied on material from Russia, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan for 25% of their uranium concentrate, 32% of their uranium hexafluoride, 14% of their conversion services, and 20% of their enrichment services. Dependence on Russia is real.

At this time, a bilateral suspension agreement (“Agreement Suspending the Antidumping Investigation on Uranium from the Russian Federation”) capping uranium imports from Russia through 2040 remains in effect. Whether Moscow will pull the trigger on rescinding the agreement ahead of time, much like its threat to exit the International Space Station project, will bear watching. Be as it may, it is worth noting that U.S. nuclear plants refuel every two years or so and typically plan their refueling cycles two to three years in advance; the fear of fuel shortages in the short-term is hence not a pressing concern.

The energy dilemma is, if anything, starker for other advanced economies. In the case of Japan, certain regional electricity companies are highly dependent on Russian Far East-origin liquefied natural gas to fulfill local demand. Burnt by the experience of having to cede its stake in a rich Iranian oilfield back to the government in Tehran in 2010 to comply with Washington’s sanctions, only to see the stake transferred to China National Petroleum Corp. (CNPC), Tokyo is leery of walking away from its existing Sakhalin gas project holdings in the Russian Far East and perhaps from its Siberian project holdings too. For now, Tokyo’s G7 commitment to phase out its Russian energy imports is restricted to oil but could extend to a phase-down of natural gas imports too in the future. By contrast, Exxon Mobil and Shell have already exited the Sakhalin 2 project, and Total is in the process of exiting the Arctic LNG 2 project. More broadly, the European Union has proposed a ban on purchases of Russian crude within six months and refined products by the end of 2022, with lengthier exceptions built-in for Hungary and Slovakia. The EU’s redirection of its voluminous oil and gas purchases notwithstanding, the trade sanctions pillar is the least crippling of the three sanctions pillars. Russia holds the whips hand, in fact, in narrow product lines within this pillar.

FIGURE 2: Sectoral Decomposition of Russia’s Gross Exports (2018)

In addition to the financial, export control, and trade sanctions, a number of other measures have been imposed too by the United States, the European Union, and its partners. These include:

These bans and restrictions apply in tandem to Belarus, too, in principle.

The view in Beijing in the late-2000s was that China should not just be a colossal technology goods exporter. It must also aspire to become a techno-globalist standard-setter and use its influence over standards, and their embedded intellectual property, to corner competitive advantage. ‘Third tier’ companies make products, ‘first tier’ companies set standards, went the refrain. Over the next decade, China became an important player in international standard-setting bodies, and none more prominently so than Huawei with its large number of 5G-linked standard-essential patents. The U.S. government’s kneecapping, nonetheless, of Huawei’s global 5G reach as well as its in-house chip design ambitions using domestic regulatory tools counsels now that Beijing set its sights higher, much beyond mere technology standard-setting.

In an era of economic warfare in which even the most plain-vanilla central bank contract is voidable, Beijing must equip itself with the capability to deny an adversary the means to dominate the chokepoints of the global economy’s infrastructural plumbing to its detriment. This does not require China to arm itself with the means to inflict an ‘economic balance of terror’. It requires rather that China be capable of employing a tailored strategy to dissuade, and if necessary, countervail a calculated disruption stemming from its exposure to the U.S. and Western-led international economic order. This could concern a transaction denominated in U.S. dollars; a U.S.-origin good, software or technology; a foreign-produced good or technology that is commingled with U.S.-origin technology; or for the matter a data packet that travels through a server, digital infrastructure, or facility located in the United States. In extremis, it could involve a situation where sanctions are even comingled, such as the simultaneous placement of a Chinese company on the Entity List and Treasury’s SDN List to choke the technology pipeline in tandem with denial of access to the dollar payments system.

In most instances, China’s capacity to dissuade will counterintuitively require more – not less – globalized trade integration, more – not less – domestic and international financial deepening, and more – not less – engagement within cross-border technology ecosystems. Russia is paying a (deservedly) steep price for its international economic and financial exposure while lacking the economic scale or broad technology base to exercise influence – much less a lock – over the key nodes of the system’s plumbing. Given the breadth of its manufacturing prowess, rising sophistication of its technology base, and potential size of the domestic market (China’s economy is already 12 times the size of Russia’s), Beijing could potentially graduate by the end-2020s to the point where it is too financially and technologically interconnected to be crippled by the West’s exercise of long-arm jurisdiction (it is already too systemically enmeshed from an international trade standpoint, as the failed Trump tariffs testify).

For this to be the case though, China’s strategy, going forward, must be informed by three precepts. First, the leadership must rededicate itself to the deepening of the reform and opening-up program, with a particular emphasis on financial deepening. The renminbi (RMB) does not need to become a full-fledged international reserve currency to bypass the sanctions dragnet. It needs only to be ‘hardened’ to the point that the People’s Bank can credibly issue unlimited amounts of currency to fulfil domestic borrowing requirements while, at the same time, instilling confidence in its store of value properties among international users to catalyze its routine use for cross-border invoicing and payments purposes. The RMB must join the handful of currencies that are actively traded in forex markets, and to get to this point, China must develop deep and liquid markets in domestic currency assets that are open to the world. Digitalization of the RMB, while welcome, is not essential; faster transactions do not amount to freer transactions.

Next, by the government’s own telling, “China’s industries’ technological level and their abilities in self dependent innovation are still low. Chinese companies lack core technology, depend on foreign companies for crucial parts, are at the lower end or the middle range of the global industrial chain, [and] rely on multinational companies for technological support …” Indigenous innovation in China cannot be built standing atop the shoulders of coerced foreign IP transfers and tilted (industrial policy) playing-field rules. It must be organically cultivated from bottom up. China must prioritize basic over applied and commercialization-related scientific research as well as incentivize the build-out of domestic scientific instrumentation-related infrastructure. Given the country’s inherent S&T strengths, these capabilities will enable it to deepen cross-border industry collaborations, rise up the technology ladder, and adapt and substitute in the face of technology embargoes.

Finally, China must be prepared to deploy at the margin tailored preventive measures to deter, and if necessary, countervail the weaponization of currency and technology. These could range from incentivizing the gradual uptake of yuan-invoicing within ‘green’ supply chains; building state capacity to trace the movement of materials and components within such chains; accelerating RMB internationalization; insisting that foreign banks install digital translators to enable their interface with China’s CIPS interbank messaging system; to threatening restrictions, if circumstances merit, against foreign insurance or reinsurance companies utilizing its Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law and Unjustified Extraterritorial Measures regulation – much like the United States’ Trading With the Enemy Act had authorized a century ago.

All along, the measures should be narrowly targeted, they should be authorized or implemented with an eye to the long view, and they should be parlayed with the intent to dissuade, not punish, the adversary’s attempt to seize the key nodes of the international system’s plumbing to prosecute economic war against China.

Ever since its rise as a great power within the European state system in the latter half of the 18th century, Russia has insisted on a free hand in dealing with its immediate European neighbors. Moreover, while Russia’s leaders have more-or-less been precise in marking out their own boundaries, they have been much less so on how far Moscow’s sphere of influence should extend. A pattern of advance followed by retreat, bred by a combination of appetite and risk aversion, has instead tended to dictate the limits of Russia’s extended strategic frontiers. In the immediate aftermath of World War II, Soviet leaders sought to consolidate their sphere of influence in Central and Eastern Europe by degrees, first by cooptation of the region’s noncommunist parties, next by engineering coup d’états, and finally through outright suppression. With memories afresh of World War II, Stalin calculated that the Western powers would not intervene in the Soviet’s backyard. And, furthermore, that the capitalist powers were too internally distracted to mount a strategic challenge to his goal of transforming the Soviet Union’s Eastern European military occupation into a network of satellite regimes.

Like Vladimir Putin today, Stalin miscalculated. Rather than view Moscow’s actions as a tactical move to accrue leverage in the inevitable diplomatic faceoff regarding the final postwar settlement in Europe, the West viewed the February 1948 communist coup in Czechoslovakia and the subsequent Berlin blockade as emblematic of the totalitarian and self-aggrandizing impulses of Soviet communism. Rather than opt for East-West negotiations, the West chose unity and a policy of containment. And like the statement of Western unity that has underlain the ‘shock and awe’ sanctions on Putin’s Russia today, the West showed by way of the Marshall Plan and the founding of NATO that capitalists could indeed reconcile their differences and find bold common purpose against Soviet provocations. Stalin, like Putin today, neither sought nor expected either outcome. Kim Il Sung’s invasion across the 38th parallel thereafter in June 1950, introducing the Cold War to Asia, testifies to the reality that the Indo-Pacific too, today, might be just one mishap away from a full-blown return to an era of zero-sum confrontation.

In one important respect though, the Western architects of the post-World War II era differed from their present-day successors. For reasons both strategic and ideological, they sought to build an international economic architecture premised on openness and universalism. American economic might and its equally mighty dollar underwrote a (Bretton Woods) system that was based on free trade, open markets, managed capital flows, and was open to all takers. Today, that very dominance of the plumbing of the international economic architecture, and the public goods that it furnished, is sought to be semi-privatized within minilateral clubs and weaponized against adversaries. Further, the turn towards economic nationalism in the U.S. is palpable. Whether these are wise or durable strategies on the part of a country that was once a beacon of prosperity, and especially at a time when most countries still seek to climb the ladder of development, remains to be seen. For better or worse, the centralized chokepoints of the 21st century’s global digital, technological, economic and financial networks have become arenas of major power contestation. The Russia sanctions was just the first chapter. More such episodes will certainly follow. Welcome to economic warfare, 21st century edition.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2025 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.