Research Associate & Program Officer

Research Associate & Administrative Assistant

The U.S.-China bilateral relationship has an enormous impact on Asian geopolitics as well as the international system and has become increasingly complex on both a security and macroeconomic level.

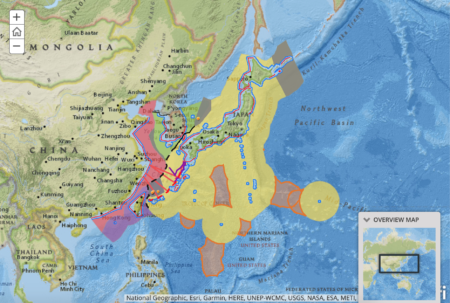

The rise of China in the maritime domain has altered the security and economic dynamics between the U.S. and its allies in the South China Sea, the East China Sea, and the Arctic. Through combining GIS with policy research, the Institute for China-America Studies (ICAS) seeks to organize and streamline these complex issues into an interactive database to create a platform that empowers and educates scholars, policymakers, students and the media through data transparency, intellectual collaboration, and well-informed analysis. In essence, the maritime trackers are living documentation of the most relevant issues and trends related to maritime security and the maritime economy.

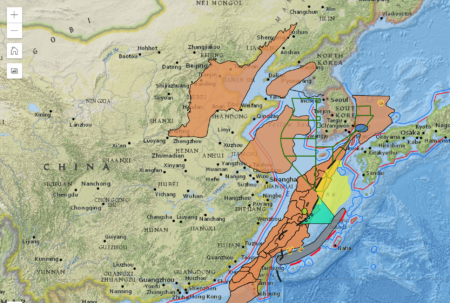

A number of maps produced by governments or research institutions display claims to maritime jurisdiction. However, many of these maps can lead to confusion and give a false impression on what the actual international claims are, as they often do not differentiate between an internationally submitted claim and a maritime rights claim featured in national legislation. Furthermore, a number of maps may also try to ‘connect the dots’, meaning that an attempt is made to connect points or lines on partial submissions or non-demarcated territorial limits to display a map that appears more complete. The trackers that ICAS produces visually differentiate each claimant’s internationally submitted maritime claims from claims made through national legislation and display all submissions/partial submissions exactly as they were presented to international bodies, such as UNCLOS.

The neighboring parties in the East China Sea region constitute roughly a quarter of the world’s population and nearly a quarter of the world’s economy. Therefore, both economic and security dynamics in the region have a significant impact on global security and economic well-being.

On an economic level, the region is home to important fisheries, hydrocarbon resources, and shipping routes. However, due to long-standing territorial and maritime rights disputes, stakeholders in the region compete over the rights to access and exploit these resources. In particular, debates over sovereignty and maritime rights in the vicinity of the Diaoyu/Senkaku/Diaoyutai Islands and the Dokdo/Takeshima Islands have led to rising tensions and standoffs in the East China Sea.

From a security perspective, the East China Sea is one of the most strategically important areas for China. The region must remain stable to guarantee sustainable economic growth. Not only is the East China Sea one of the only two access points for China to major oceans, but in addition, most of China’s developed cities reside on the eastern shore.

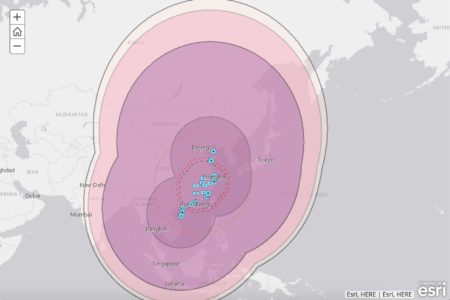

China is currently undergoing a naval modernization program that comports with its evolving role as a rising global power. In its 2015 military textbook The Science of Military Strategy, China indicated that the role of its navy has shifted from “near-sea defense” to “far-sea protection”. China follows an “active defense” doctrine, which directly influences its offshore defensive strategy. In addition, China believes that it needs a modern blue-water navy to support its growing ocean-faring interests, including the protection of its sea lines of communication.

The region is also very important to the U.S. and other Asian powers, including South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan. The United States sees the region as essential to its forward-deployed posture of securing a favorable strategic balance in the Indo-Pacific region. While the U.S. relies on its allies in the region to support its great-power competition with China, its military dimension impacts the strategic and power dynamics in the region.

Within the constraints of Japan’s pacifist constitution, the Abe administration, too, has sought to boost Japan’s defense capability. The Japan Self-Defense Force is currently developing strong stand-off capabilities to defend its southwestern remote islands, including the deployment of rapid reaction forces from its main islands.

Given its manpower constraints, Taiwan’s defense strategy focuses on establishing multilayer defense and creating asymmetric local superiority against a potential amphibious invasion. In this regard, Taiwan’s military has been seeking out more purchases of cutting-edge U.S. weapons and equipment.

On June 14, 2019, ICAS published its pilot tracker on Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOP) in the South China Sea. Taking lessons learned from the FONOP tracker, we are now entering into the first phase of the East China Sea Tracker. For the sake of completeness, we include the Yellow Sea and the Japan Sea regions in the East China Sea Tracker to incorporate the full extent of maritime claims, economic activities, and security elements.

Phase I of the East China Sea Tracker focuses on three main elements:

The Maritime Claims Trackers explore long-standing territorial and maritime rights disputes that largely remain unsettled to this day. We make a distinction between claims that have been submitted to international bodies, following the entry into force of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), and claims that are more rooted in national laws and norms. In areas where maritime boundaries are in dispute, we show the claims of each party based on the best publicly available information. ICAS emphasizes that these maps are not to be taken as an endorsement of any one party’s respective claims over another’s.

The Maritime Economy Trackers emphasize economic activity in this maritime region. Given the overlapping and disputed sovereign rights and jurisdiction claims in the East China Sea, economic activity, such as commercial fishing and hydrocarbon exploration/exploitation, has necessarily become highly politicized in some cases. This has led to disputes regarding the access and utilization of potential and existing resources. As such, the first two economic trackers place an emphasis on fishery agreements and hydrocarbon exploration/exploitation.

The Maritime Security Trackers explore power dynamics in the region that have a direct impact on China, the U.S., and other parties with strategic interests in the region. In the first phase of the ECS tracker, we seek to show the power dynamics between China, Japan, the U.S. Force Japan, and Taiwan.

Phase I of the ECS Tracker places emphasis on the U.S.-China, U.S.-Japan, and Japan-China relationships. In Phase II, the aim is to provide a broader snapshot of the region writ-large, as well as cover geographic theaters that have hitherto been covered lightly or skipped altogether. These include the evolving strategic dynamic in the Taiwan Strait, in the Sea of Japan/East Sea featuring the two Koreas as well as Japan, in the Northern Pacific featuring Russia and Japan and in the Western Pacific, featuring the U.S.’ deployments in Guam and in and around the second island chain. Where parties have competing sovereign rights and jurisdiction claims in the relevant sea areas, these will be mapped out too.

As the East and South China Seas are connected physically, so too are many economic and security elements in both seas. Therefore, once revisions and new additions take place during the second phase of the South and East China Sea trackers, ICAS plans to connect the two seas together.

In the backdrop of increasingly tense bilateral relationships, such as the U.S.-China relationship and the Japan-South Korea relationship, it is the goal of ICAS to use these trackers to build a platform for intellectual exchange that spans across institutions and sectors to promote greater multilateral cooperation and regional stability. As more trackers continue to be developed in the near and long term using new data tools and programs, the scope and breadth of study will grow as well. In this regard, the platform will become an online community and forum that welcomes both data sharing and discussion that allows for fact-checking and deeper analysis.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2025 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Opinion | As China modernises its navy, the US races to stay ahead