Members of the Philippine Navy Special Operations Group, U.S. Navy SEAL, and Australian Operator with 2nd Commando Regiment, Special Operations Command, conduct an amphibious raid during Balikatan 22 at El Nido, Palawan, Philippines, April 1, 2022. (Source: U.S. Marine Corps photo by Sgt. Mario Ramirez, Public Domain)

Research Assistant

Manila’s recent deepening of military cooperation with the United States is motivated by a perceived need to enhance the Philippines’ maritime security and reinforce its position in disputes with other claimant states—primarily China—in the South China Sea.

Washington takes no official position on sovereignty disputes in the South China Sea, but its overall strategy to promote international maritime law and deter Chinese transgressions in the region substantively aligns its interests with the renewed resolve of Philippine President Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos Jr., inaugurated last June.

The Philippines’ disputed claims in the South China Sea operate on two levels: disputed jurisdiction over maritime space, and disputed sovereignty over mid-ocean territorial features. Both of these categories trace their legal origins back to the Philippines’ time as a U.S. colony between 1898 and 1946.

Manila’s rights to resources and jurisdiction in maritime zones extending from its coastline are disputed with Beijing’s overlapping claims to “historic rights” in the South China Sea and jurisdiction over “relevant waters” around its controlled islands. The Arbitral Tribunal established under Annex VII of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) ruled in 2016 that China was violating Philippine rights in its entitled maritime zones, but disputes over fishing and hydrocarbon exploration between the two states persist.

The Philippines is also engaged in territorial sovereignty disputes with its neighboring states over several islands, reefs, and underwater features in the South China Sea, namely: the Scarborough Shoal, which it disputes with China, and parts of the Spratly archipelago, which it disputes with China, Vietnam, and Malaysia. Both disputes are mired by complicated histories, precarious legal arguments, and ‘might makes right’ attitudes.

With the recent expansion of U.S.-Philippine security cooperation, Manila has an opportunity to shrewdly pursue constructive diplomacy with other claimant states alongside targeted maritime capacity-building measures with Washington’s assistance. The Biden administration may facilitate both ‘tracks’ if it wishes to positively contribute to regional stability and mitigate the escalation of tensions.

This week, the annual Balikatan joint military exercise will commence in the Philippines. This year’s drills will be the largest yet, with 17,600 Philippine, U.S., and Australian troops expected to participate. Notably, exercises will be conducted on Palawan, a Philippine island flanking the South China Sea. Ever since the inauguration of Philippine President Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos Jr. last year, the country has placed a renewed focus on the South China Sea in what has been hailed by analysts as a “strategic reboot” and “renewal” of a U.S.-aligned, China-critical outlook. In the maritime domain, the Marcos administration has revived a 2016 Award by the Arbitral Tribunal established under Annex VIII of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) as a rhetorical tool against China’s claims in the South China Sea. Marcos Jr. has also stood up more resolutely against encroachments by China in the Philippines’ claimed maritime zones.

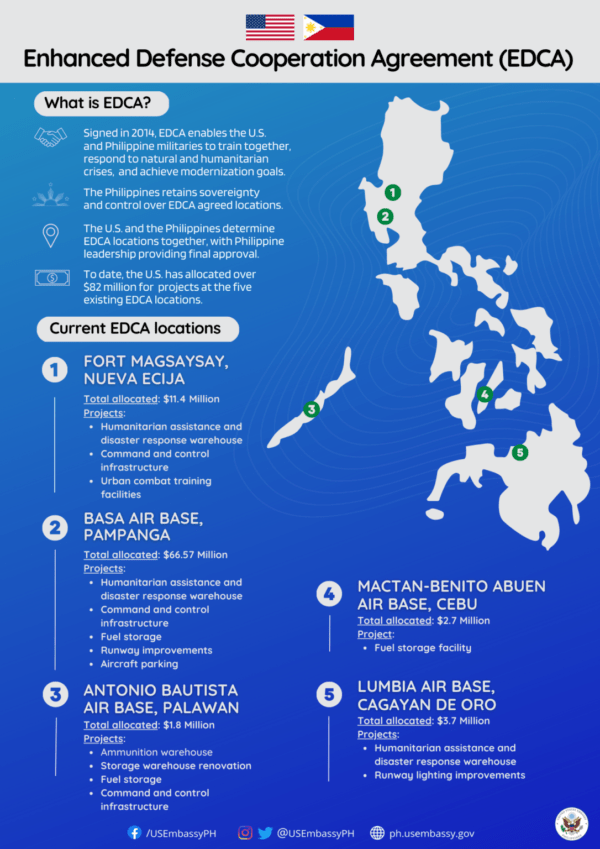

The impact of the pivot was fully laid bare in early February. In breaking with the U.S.-leery policies of the previous president, Rodrigo Roa Duterte, Marcos Jr. announced an expansion of the 2014 U.S.-Philippine Enhanced Defence Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) on February 1, paving the road for U.S. access to four more Philippine military bases in the coming months; up from the current five bases with a rotational American presence. In doing so, Marcos Jr. surmounted an undercurrent of anti-U.S. sentiment in the Philippines, owing to American colonialism, which reached its zenith in 1991 when the Philippine Senate gave the United States a one-year ultimatum to vacate its naval base at Subic Bay—once the cornerstone of U.S. naval strategy in the Pacific west of Guam. The augmentation of this EDCA was timely: just days after its announcement, a Philippine Coast Guard patrol in one of Manila’s claimed features in the Spratly Islands was greeted by a military-grade Chinese laser, prompting outrage and further galvanizing Manila to seek out support against Beijing.

The emerging rehabilitation of the U.S.-Philippine alliance after a rocky half-decade shows that Manilla perceives a need for support from the U.S. to preserve its sovereignty and jurisdiction at sea. Washington, in turn, sees a central role for the archipelago in advancing its ‘soft power’ initiatives to promote a “rules-based approach to the maritime domain,” as well as its ‘hard power’ efforts to deter China from regional “bullying.” Understanding the roots of the Philippines’ interests in these waters, and the role played by U.S. support, is crucial to determine how both states may influence events in the region going forward.

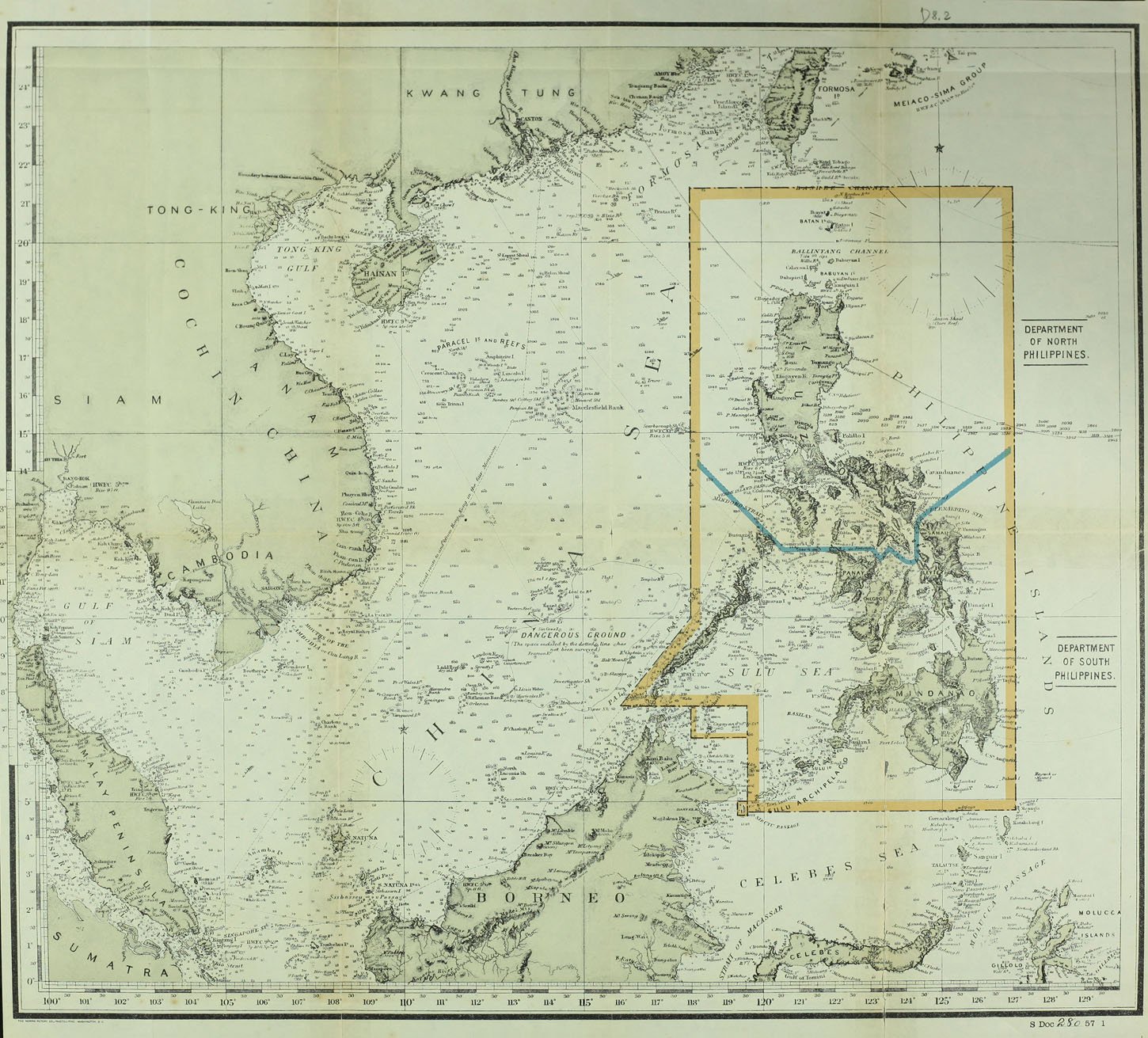

While economic activity by Filipinos and other coastal populations in the South China Sea goes back millennia, the legal basis for the Philippines’ contemporary claims in the sea’s eastern reaches was established through local-colonial interaction. Despite ongoing debates about the application of Western-based international law in colonized spaces, Spanish and American concern over the Philippines’ boundaries has actually worked to Manila’s favor on aggregate. When the U.S. defeated the Spanish in the war of 1898, the resulting Treaty of Paris ceded, inter alia, colonial jurisdiction over the Philippine islands as defined by a ‘box’ surrounding the archipelago. However, Washington shortly began to adjust the borders of its new acquisition in bilateral negotiations with neighboring colonial powers. For example, a follow-up treaty with Spain appended the outlying islands of Sibutu and Cagayan de Sulu to the Philippines in 1900, it lost the island of Palmas (Miangas) to the Dutch East Indies in a 1928 international arbitration case, and it gained the Turtle and Mangsee Islands from British North Borneo in a 1930 treaty.

The over-simplicity and evident malleability of the original treaty ‘box’ also led the Philippine government to internally lay claim to the Scarborough Shoal (Bajo de Masinloc, Huangyan Dao) in 1938 despite its falling nine miles outside of the 1898 treaty limits. In correspondence between Manila, the U.S. High Commissioner, and the Secretary of State, the U.S. concluded that, because of the shoal’s proximity to Luzon and a history of Spanish responsibility for rescue operations there (as well as “the absence of other claims”), “the shoal should be regarded as included among the islands ceded to the United States by the American-Spanish Treaty.” The fact that these claims were not publicized, however, detracts from their finality in international law. Arguably, it was not until 1965 or 1997—when the Philippines planted flags on the rocks of the shoal, with no sustained presence in the first case—that the first clear articulation of sovereignty over the shoal can be found per the standards of international law.

In spite of this flexibility, the insular Senate in Manila passed a law in 1932 declaring all waters within the Treaty of Paris ‘box’ as Philippine territorial waters—one year before Washington granted autonomy to the Philippines as a commonwealth. This geometric basis for determining the internal waters of the Philippines was eventually retired in 1961 when Manila enclosed the waters within the archipelago through a system of straight baselines and declared them subject to its sovereign jurisdiction. These baselines were amended by law in 1968 and joined by a presidential declaration which proclaimed that “the continental shelf adjacent to the Philippines [of indeterminate limits]…[is] subject to its exclusive jurisdiction and control for purposes of exploration and exploitation.” An exclusive economic zone (EEZ) extending specifically 200 nautical miles (nm) from these baselines was established by law in 1978.

Most recently, in 2009, the Philippines brought its maritime claims more clearly in line with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) through Republic Act No. 9522. This act declared a system of archipelagic baselines that comply with Article 47 of UNCLOS and adjusted the Philippine territorial sea and EEZ to conform with these alterations. By then, the Philippines had also clarified that its continental shelf claim extended out to 200 nm in an effort to bring its seabed claims in line with Article 76 of UNCLOS in 1994—the year the Convention came into force. With these adjustments, the Philippines has effectively replaced the ‘treaty box’ as the basis for its maritime claims with its UNCLOS entitlements as an archipelagic state. However, pre-UNCLOS laws and treaties continue to undergird Manila’s claims in the South China Sea, most notably those in the Spratly Islands which lie beyond 200 nm of its baselines.

While Manila no longer considers the treaty limits established in 1898 to be its territorial waters, the Philippines is similar to China among South China Sea claimant states in that it continues to assert sovereignty over a geometric area, rather than on an island-to-island basis, in the Spratly Islands. Philippine claims in parts of the Spratlys were first internally articulated by Filipino politicians and insular officials during a year of agitation that followed French Indochina’s 1933 annexation of seven features in the western parts of the archipelago, but the contemporary Philippine claim was not officially pronounced until after the Second World War. In 1956, an expedition of Filipino fishery and guano prospectors claimed several islands in the eastern part of the Spratly group, but were boarded and questioned by Taiwanese naval forces in the area. When the party returned home, a larger Taiwanese force arrived and confiscated the property left behind by the Filipinos.

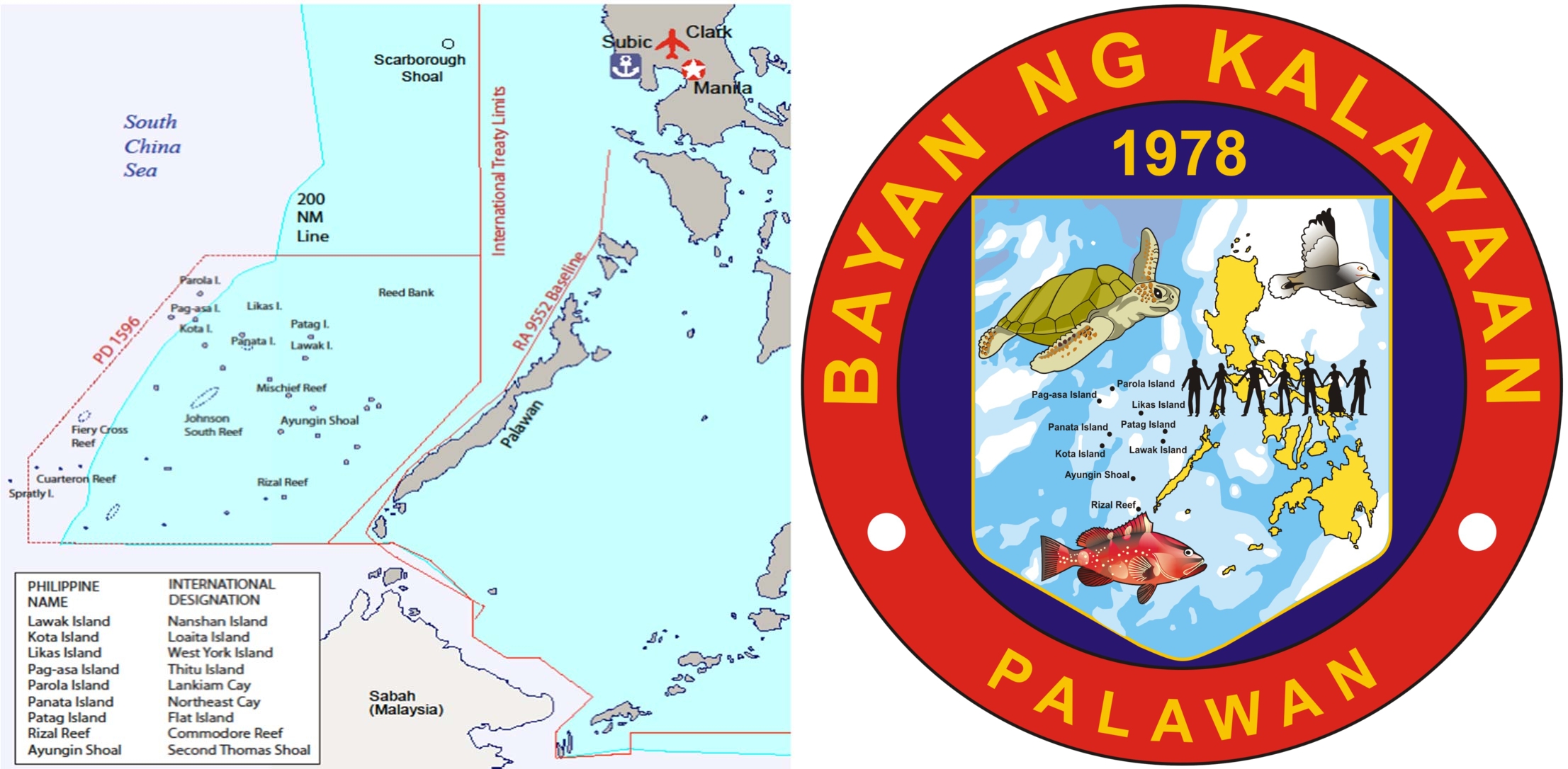

After a decade of appeals to the Philippine government for aid, the military moved to secure several features with Philippine commercial interests at the end of the 1960s. In 1979, with Presidential Decree 1596, Manila formally asserted a claim to “the seabed, subsoil, continental margin and air space” within a hexagonal area off of the west coast of Palawan (roughly corresponding to the eastern islands of the Spratly archipelago referred to as ‘Dangerous Ground’ on several nautical charts) and named it the ‘Kalayaan Island Group’ (KIG). The government claimed that the islands and underwater features within the claimed area “by reason of their proximity…are vital to the security and economic survival of the Philippines.”

The geometric claim remains on the books, but it has been practically dormant since the 70s when the Philippines initially established control over the nine features which it administers as the KIG. While the Philippines still asserts sovereign jurisdiction over a few Chinese and Vietnamese-administered features in the western parts of the hexagon, its most pernicious disputes are over features within its 200 nm continental shelf and EEZ—the dispute over the populated Thitu (Pag-asa) Island, beyond 200 nm (see Figure 3), is a complicating exception. Manila has also taken steps to bring the KIG claim in line with UNCLOS, such as by describing its administration of the group as a ‘regime of islands’—conforming to language within Article 121 of UNCLOS—in its 2009 baseline law. Nevertheless, the specific islands that constitute this ‘regime of islands’ have never been explicitly defined by Manila, which continues to assert its KIG claim in terms of the boundaries “constituted under Presidential Decree No. 1596.”

U.S.-Philippine relations have had a troubled history since Washington assumed the colonial mantle from the Spanish in 1898, with the relationship, more often than not, subsuming Philippine autonomy beneath U.S. geopolitical interests in the Pacific. The Philippines was swept into the Second World War just hours after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, and fell to the Japanese in a four-month campaign (interestingly, launched from Taiwan and secret Japanese bases in the Spratlys—an early example of the islands posing a security concern). After the Philippines’ successful liberation during WWII by local guerillas and U.S. forces, it declared its independence in 1946 but remained an integral part of the nascent U.S. Cold War strategy as part of the first ‘island chain.’ Even before the United States’ infamous involvement in Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War, Manila sought Washington’s cooperation in its post-war counterinsurgency campaign against lingering anti-Japanese communist guerillas.

In 1951, the two sides signed a Mutual Defense Treaty (MDT) which cemented the Philippines’ position as a U.S. ally in the Cold War. Unique among mutual defense commitments, Article V of the MDT defines the conditions of its invocation as:

“an armed attack on the metropolitan territory of either of the Parties, or on the island territories under its jurisdiction in the Pacific or on its armed forces, public vessels or aircraft in the Pacific.”

Following the malaise of the Vietnam War, Washington was wary to publicly commit to a defense commitment in the South China Sea, so the Carter administration privately communicated to the Philippines in 1979 that “an attack…would not have to occur within the metropolitan territory of the Philippines or island territories under its jurisdiction in the Pacific in order to come within the [MDT’s] definition of Pacific area.” However, after the end of the Cold War, the Clinton administration publicly affirmed in 1999 that “the US considers the South China Sea to be part of the Pacific Area.” Since then, the MDT’s application to the South China Sea has been consistently reaffirmed by Washington and it continues to be the cornerstone of the U.S.-Philippine alliance. However, its unique phrasing leaves room for substantial flexibility regarding assaults on non-governmental actors or harassment of official forces that does not rise to the level of an “armed attack.”

Recent Developments in U.S.-Philippine Security Cooperation

While the U.S.-Philippine Mutual Defense Treaty remains solid and clear in scope, the permanent U.S. military presence in the Philippines ended in 1992, a year after the Philippine Senate rejected a treaty that would have renewed the expiring U.S. basing rights in the country. The modern instrument of U.S.-Philippine security cooperation is the Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA), which came into force in 1999, supplemented by the EDCA of 2014 which was further expanded earlier this year. Under this framework, U.S. forces are allowed rotational access to designated Philippine military bases under Manila’s oversight while Washington retains legal jurisdiction over its deployed personnel. The two militaries have used these rotational deployments to engage in mutual training operations (especially during the ‘Global War on Terror’ and more recently in response to the rise of China) including the annual Balikatan military exercise.

Relations grew strained in 2016 as former Philippine President Duterte was generally skeptical of how the increasing U.S. regional presence during the ‘pivot to Asia’ would affect Philippine security. He sought instead to mollify China, diversify Manila’s security partnerships, and reduce its dependence on the U.S. for security. As part of this outlook, Duterte made a few attempts to cancel the VFA between 2020-2021, but U.S. and Philippine defense officials ultimately convinced him to keep the agreement in place. His more U.S.-friendly successor Marcos Jr. continues to build upon existing U.S.-Philippine security agreements. Notable among these intensified ties is the proposal found in the recent round of EDCA negotiations to allow U.S. forces access to four more bases in northern Luzon and Palawan. These are areas that would be crucial in any conflict between the U.S. and China over Taiwan or the South China Sea.

The Philippines continues to be locked in maritime and territorial disputes with other claimant states in the South China Sea, most notably China. Sino-Philippine confrontation in the South China Sea first manifested in 1995 when China occupied and began constructions on the submerged Mischief Reef in the eastern part of Manila’s claimed ‘Kalayaan Island Group.’ The Philippines responded in 1999 by deliberately grounding a WWII-era amphibious vessel on the nearby Second Thomas (Ayungin) Shoal which Manila continues to use as a base. In 2005, the Philippines came to a joint agreement with Vietnam and China to explore the Reed (Recto) Bank for oil and natural gas deposits, but the agreement lapsed and was not renewed by Manila in 2009 amid a wave of Beijing-linked corruption scandals and skepticism over unilateral concessions to China in its newly-defined 200 nm EEZ and continental shelf. When a British surveying firm was awarded an exploration contract by the Philippines and entered the area in 2011, it was scared off by Chinese patrol boats asserting that the site was disputed and not under exclusive Philippine jurisdiction. In 2012, a standoff occurred in the Scarborough Shoal (which was incorporated into Philippine civil government in 2009) that resulted in China taking over control of the feature after Philippine vessels were forced home due to inclement weather. Despite protests from Manila that the militarization of the standoff should have resulted in the invocation of the MDT, the U.S. chose ambiguity in this episode, expressing its support for the Philippines against China’s encroachment while officially taking no side on the merits of the Philippines’ claim.

Washington’s fine line between maritime and territorial disputes warrants a more precise explanation of what distinguishes the two categories. On the purely maritime level, Manila disputes China’s claims to (1) ‘historic rights’ in the South China Sea and (2) jurisdiction over the waters and seabed extending from its claimed islands in the South China Sea (approximated by the ‘nine-dash line’), and alleges that they violate UNCLOS provisions about the legal extent of a state’s EEZ and continental shelf. The Philippines also disputes Malaysia’s 2019 claim to an extended continental shelf (ECS) in the South China Sea. While claims to the seabed beyond 200 nm are permitted by UNCLOS under certain geographic conditions (e.g., the thickness of the sea-floor sediment and the gradient of the submerged continental slope), Malaysia’s disregard for these provisions in laying claim to deep seafloor in the ‘donut’ beyond the natural continental margin of the littoral states has garnered protests from all of its neighbors. Manila’s maritime disputes with China, however—both within 200 nm of the Philippines’ western baselines (a maritime zone known to Filipinos as the ‘West Philippine Sea’) and the 12 nm territorial seas around its claimed islets in the Spratlys—are more salient in light of the two states’ naval power imbalance and patchy diplomatic record.

Unable to effectively challenge China through bilateral force or dialogue, Manila made an attempt to rectify its encroachment into Philippine maritime zones supranationally in 2013 by bringing a claim against China in an Arbitral Tribunal (provided for under Annex VII of UNCLOS). In an attempt to sidestep China’s non-recognition of UNCLOS-based compulsory dispute settlement in matters such as disputed maritime boundaries and sovereignty, the Arbitral Award of 2016 dealt only with China’s purported claim to maritime rights within the nine-dash line, the legality of Chinese activity in the Philippines’ EEZ, and the legal status of the features under dispute. In other words, the Tribunal was to determine whether they are islands (capable of generating a 12 nm territorial sea and a 200 nm EEZ), rocks (capable of generating only a 12 nm territorial sea), or low-tide elevations (with no capacity to independently generate maritime zones). No features were designated as ‘islands’ because the Tribunal decided that none of the features above tide were capable of sustaining life in their natural state; however, several features were determined to be ‘rocks,’ including the Scarborough Shoal and several disputed islands in the Spratly archipelago (see Figure 7 for detail).

On matters of territorial sovereignty, the Philippines’ contentions with its neighbors in the South China Sea are mired by the historical complexities of the disputed islands (and, in China’s case, other features and adjacent waters within the nine-dash line). Concerning the Scarborough Shoal, Manila’s claim is often challenged by referencing that the feature fell outside of the limits established in the treaties which transferred the Philippine islands from Spain to the U.S., and in turn from the U.S. to the Philippine Republic. However, the aforementioned colonial-era actions and correspondences that testify to the shoal’s geographic unity with the rest of the archipelago, and the manifest flexibility of the original treaty limits, complicate the dispute. Today, Filipino scholars also reference that the shoal lies upon the Philippines’ continental shelf and that the Philippines was the first to assert sovereignty over the shoal specifically (in either 1965 or 1997) in contrast to China’s earlier, but nebulous, nine-dash line.

Philippine claims in the Spratlys are perhaps more questionable. Manila’s 2009 claim to a ‘regime of islands’ in the Spratlys remains predicated on its 1979 presidential declaration which established the ‘Kalayaan Island Group.’ This hexagonal claim is subject to similar sorts of criticism as China’s nine-dash line for failing to articulate sovereignty over specific features and instead asserting jurisdiction over an entire expanse of maritime space. Manila’s public claim in the Spratlys also came later than those by France and China, and was premised on proximity, national security, and contemporary economic activity rather than historic use. However, evolving Philippine rhetoric, maps, and legal designations of the KIG suggest that Manila, in practice, only treats its administered features and the surrounding waters as its sovereign territory and has a particular interest in resisting encroachment into features which lie upon its 200 nm continental shelf. This does not fully resolve its persistent disputes with Vietnam (over the Philippine-administered islands beyond 200 nm that are explicitly named in the French annexation notice of 1933), Malaysia (concerning Sabah and the overlapping continental shelf claims), or with China’s all-encompassing nine-dash line, but it does suggest a substantial reduction of features under serious dispute.

The Washington Factor

As referenced earlier, Washington takes no official stance regarding sovereignty disputes in the South China Sea and it highlights freedom of navigation as its primary interest in the waters. However, despite the Duterte administration’s purposeful de-emphasis of the 2016 South China Sea ruling, in 2020, the U.S. State Department issued a revision of its position on maritime claims in the South China Sea that brought the U.S. position in line with the ruling’s findings regarding the merits of Philippine and Chinese maritime claims. Since then, the U.S. has welcomed Marcos Jr.’s renewed assertiveness in the maritime domain, particularly after an incident earlier this year where the Chinese Coast Guard reportedly shined a powerful laser against a Philippine Coast Guard vessel operating in the Second Thomas Shoal “causing temporary blindness to her crew at the bridge.” In response to the encounter, the U.S. State Department echoed the findings of the 2016 ruling saying “the People’s Republic of China has no lawful maritime claims to Second Thomas Shoal” as a submerged feature on the Philippines’ continental shelf.

In the wake of the incident, which occurred the same week as Manila and Washington agreed to increase U.S. access to Philippine bases through the EDCA, President Marcos Jr. shared his outlook with a graduating military academy class: “[t]his country will not lose one inch of its territory. We will continue to uphold our territorial integrity and sovereignty in accordance with our Constitution and with international law.” Speaking later to active troops, Marcos Jr. added that “your mission in the [Armed Forces of the Philippines] has changed…For many, many years, we were able to maintain that peace and maintain that understanding with all of our neighbors. Now things have begun to change and we must adjust accordingly.” Further supporting this inflection was a January 2023 decision by the Supreme Court of the Philippines which, for good measure, struck down the constitutionality of the obsolete 2005 joint resource exploration deal with Vietnam and China. Taken together, these recent escalations have freed Marcos Jr.’s hand to discard his predecessor’s conciliatory approach to disputes with China.

While Marcos Jr. does not wish to be a mere lackey of Washington, unlike his predecessor Duterte his resolute position on disputes with China in the South China Sea has led him to view collaboration with the U.S. as a boon to the Philippines’ national security rather than a liability. The burgeoning ‘new normal’ of increased U.S.-Philippine military cooperation will likely proceed hand-in-hand with the coordination of efforts to legitimize the latter’s position in the South China Sea. Manila’s tact for international maritime law plays into Washington’s peacetime interest in upholding UNCLOS principles such as freedom of navigation, while the Philippines’ strategic position within any potential U.S.-China conflict affords it substantial leverage in garnering U.S. support for its national interests.

An exploration of the origins and nature of Philippine and U.S. interests in the South China Sea reveals a substantial degree of alignment. While this harmonization ought to be availed for the purposes of regional stability, increased tensions in the U.S.-China relationship will likely lead Manila to pursue more assertive policies towards Beijing as it hitches its wagon to Washington more thoroughly. However, given that China is a close neighbor and trade partner to the Philippines, Manila could also pursue a parallel set of policies to manage tensions and capitalize on areas for potential cooperation. But this room for maneuver is narrowing. The recent decision of the Philippine Supreme Court has left joint fishery and resource exploration efforts stillborn so long as China insists on equal ownership of the maritime zones in question. Therefore, Manila’s foreign policy in the short term will likely prioritize minilateral coalition-building against China as its main diplomatic thrust, safeguarded by limited, de-escalatory engagement with Beijing. This will proceed alongside a more comprehensive program of U.S.-backed military capacity building to deter Chinese incursions in the maritime domain.

Expected Policies from the Philippines:

Manila’s anxiety over China’s actions in the South China Sea has left Washington holding most of the proverbial ‘cards’ in the U.S.-Philippine relationship right now. The allure of bolstering Manila to act as a regional proxy in its troubled relationship with China is surely a tempting offer for the White House. However, domestic and geopolitical factors are pointing towards a policy equilibrium. In an effort to present itself as a ‘responsible stakeholder’ in the South China Sea, the Biden administration will likely continue embracing Marcos Jr.’s pivot while taking care not to unduly escalate global tensions by hastily revolutionizing the regional balance of power.

Expected Policies from the United States:

While this robust “transformation of the U.S.-Philippine alliance” has the potential to outperform Duterte’s ‘holding pattern’ in the South China Sea, it also carries significant risks. Marcos Jr., in departing from his predecessor’s tacit agreements with Beijing (however discriminatory and flimsy they may have been), has reawakened an assertive China in his neighborhood. Beijing may very well view any U.S. security ties with the region as a provocation, but it will certainly do so if the proliferation of force proceeds without qualification. If Manila and Washington truly wish to avert conflict and play a constructive role in the South China Sea, they must heed the Rooseveltian maxim to “speak softly and carry a big stick”—perhaps with a division of labor. Washington can tip the regional balance of power, but it must facilitate Philippine engagement with the range of like-minded, ambivalent, and oppositional claimant states if it wants its capacity-building to be interpreted as contingent and deterrent. Without these appeals, it will only be seen as an aggressive escalation which, with the added ingredient of a defense commitment, is a dangerous recipe.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2026 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Rome’s Arctic Message: Observer Participation and Competing Greenland Narratives