When ecosystem management and marine life conservation come to mind, Antarctica and its surrounding waters are rarely considered by the average person. However, as one of the few relatively pristine ecosystems left in the world, Antarctica’s fisheries are becoming increasingly important as ocean warming could cause catch from the world’s fisheries to decline by as much as 24.1 percent in the 21st century, according to the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Add in the compounding effects of overfishing and illegal fishing, and the maximum catch yield could be further impacted. Communities dependent on fishing for their income, livelihoods, and food security would be significantly affected by such a decline, not to mention the potential global economic consequences for a critical industry to decline so drastically. Maintaining the massive ocean and sea regions surrounding Antarctica is essential to mitigate these impacts.

Fortunately, an international body already exists to conserve these resources. The Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) was established in 1982 in response to increased commercial interest for fisheries in the region. CCAMLR is an international commission with 26 member states and an additional ten countries that have acceded to the convention. As members of CCAMLR, both the United States and China are responsible as critical stakeholders in the region. They are obligated by the Commission to engage in scientific research and work with the other members to determine adequate measures for the conservation of marine resources.

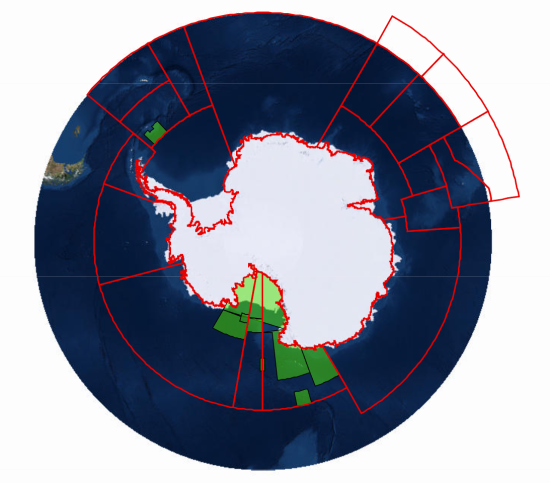

CCAMLR is responsible for establishing marine protected areas (MPA) and deciding on commercial catch limits in the various regions of the convention area. Member states must deliberate and agree to implement these measures in the Convention Area, representing roughly 10 percent of the Earth’s oceans. Given that the United States and China are both key members of a Commission that manages such a large proportion of the world’s marine regions, their ability to cooperate, or lack thereof, has potentially enormous consequences for the sustainability of an area containing some of the world’s most important fisheries and research zones.

Such cooperation has resulted in crucial protections for Antarctica in the past, such as establishing the world’s largest marine park in the Ross Sea off the southern coast of the continent in 2009, which entered into force in December 2017. However, several recent MPA proposals were on the table in October 2021 that, if passed, would have more than doubled the area currently protected. On April 28, 2021, the United States, led by John Kerry, the Special Presidential Envoy for Climate, signed a Joint Declaration released by the European Union that signified their support for the additional proposed MPAs in the Weddell Sea, the East Antarctic, and the Antarctic Peninsula. In the discussions leading up to the decision, it was clear that both Russia and China had been hesitant to support them and ultimately opposed their establishment in 2021. The two countries cited that they required additional scientific evidence and expressed a desire for more elaboration on the exact definition of an MPA. With only 18 out of 26 members voting for establishing these MPAs, the measures failed to pass this past year.

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) and MPA Planning Domains in the Antarctic.

Source: ICAS Antarctic Tracker

One would be safe to assume that geopolitical competition can significantly determine whether a country voted for or against the establishment of these MPAs. There are, of course, economic considerations at play as well, given that Russia and China have displayed a vastly increased interest in harvesting living resources, such as krill, in the Southern Ocean. However, one should not discount other factors, such as ensuring that the MPAs are established using the best available science and receive realistic and practical enforcement mechanisms. For example, speaking at an event at the Wilson Center, Dr. Guifang Xue of Shanghai Jiao Tong University expressed that China’s own complicated experience in domestic governance of its own MPAs influences how it looks at the multilateral management of MPAs. According to her, numerous obstacles exist that can negate the effectiveness of MPAs, such as insufficient operating funds, low levels of enforcement, and a general lack of public awareness. If an MPA suffers from such deficiencies, it will merely exist on paper and be continuously violated, intentionally or not, in the real world.

CCAMLR has much to accomplish in 2022, and it is likely that deliberation on the establishment of the three proposed MPAs will continue, with the United States and China playing a significant role. It should also be noted that although these MPAs were rejected by China and several other countries, this does not necessarily imply that they do not eventually want them to be established. This is evidenced by both Russia and China joining each other in an official communique issued by the G20 in July 2021 that stated for the first time full support for CCAMLR and recognition that MPAs “can serve as a powerful tool for protecting sensitive ecosystems representative of the Convention Area, in particular in East Antarctica, the Weddell Sea and in the Antarctic Peninsula.” While opposition to establishing new MPAs on its face sounds counterproductive to addressing urgent issues such as overfishing and climate change, there is something to be said about ensuring their efficacy.

During the 40th annual meeting of CCAMLR in 2021, the European Union and its Member States, with support from non-EU CCAMLR Member States, submitted a statement lamenting the lack of progress on the passage of the three MPAs; they did acknowledge the importance of consensus-building for their “design, designation, implementation, and establishment.” At a time when strategic competition has resurfaced between major powers to levels unseen since the Cold War, it is easy to lump together all areas where diverging positions between the U.S. and China appear through that lens, even in the realm of environmental protection. Those more significant geopolitical issues should not be discounted as potential influencing factors, but disregarding CCAMLR’s processes for carefully designating MPAs would amount to willful ignorance even in the face of continued disagreement.

——————–

In light of the growing importance of Antarctica and its living resources, the Institute for China-America Studies has expanded its Antarctic Maritime Issue Tracker to include a visualized and interactive information tool for understanding the role that CCAMLR plays in sustainably managing fisheries and encouraging collaborative scientific research. To learn more about these resources, the ICAS Tracker can be viewed here.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2025 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Diverging Currents: U.S.–China Strategies on Deep Seabed Mining and the Future of Ocean Governance