- Blog Post

- Amanda (Yue) Jin

Photo Source: The official flag of the World Trade Organization (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Resident Senior Fellow

Later next week, the Appellate Body (AB) of the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) dispute settlement system will cease to function, owing to the lack of a quorum stemming from the Trump Administration’s exercise of a veto on new AB appointments. The falling into disuse, potentially, of the WTO’s dispute settlement function is a huge blow to multilateral governance.

The driver of the U.S.’ veto, and key dissatisfaction with the Appellate Body’s functioning, is its view that the AB has: (a) repeatedly overstepped its role and mandate assigned at the time of the WTO’s founding in the mid-1990s; and (b) that the U.S.’ WTO partners are unable or unwilling to provide the requisite remedial comfort on this grievance. The former accusation holds merit; the latter is meritless. WTO Member States have introduced constructive proposals that substantially redress the U.S.’ disquiet surrounding the AB’s overreach.

The Trump Administration’s Appellate Body-related grievance is one facet – albeit the most prominent one, of a larger list of grievances leveled by Washington against the WTO. The philosophical roots of the grievances derive from its ‘America First’ nostrums. Two elements are key: first, that America will henceforth engage with foreign trade partners and foreign trade liberalization strictly on the basis of bilateralism; and second, that America will not in principle submit to third party arbitral or enforcement mechanisms.

The larger list of the Trump Administration’s WTO-related grievances range from the inability of the organization’s rules to discipline the global market distorting effects of China’s state-run policies and practices, to the tardy pace of WTO Member States’ fulfilment of their transparency and notification requirements, to the alleged abuse of special and differential treatment-related self-designation rights by a number of wealthy and advanced developing countries.

China features prominently in each of these grievances. It is either engaging in unfair practices that go against the purposes of the multilateral trading system or, alternatively, the system with the WTO at its core is incapable of reining-in China’s policies and practices. China is also abusing its rights and privileges within the institutional set-up of the WTO, both by claiming developing country status and by being tardy in its transparency and notification obligations. The dispute settlement system is unable to bring Beijing to book too.

Regardless of the merits – and demerits – of the Trump Administration’s ‘America First’ policies, the WTO-centered trading order is approaching a critical fork in the road. Its rulebook desperately requires updating to keep pace with cross-border commercial developments, both in terms of the means of trade flows (most notably in the area of digital commerce and data flows) and in the type of players involved (notably state-owned enterprises – SOEs). For its part, China would be well-served too by inscribing a number of industrial policy-related reform principles and practices, particularly as its growth model transitions from high-speed to high-quality growth.

Barring a last-minute reprieve, on 11 December 2019, one of the crown jewels of multilateral governance, the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) dispute settlement system – and, in particular, the functioning of its Appellate Body (AB) – will grind to a halt. The AB, established in 1995 under Article 17 of the Understanding on Rules and Procedures Governing the Settlement of Disputes (DSU), is a standing body that hears appeals from reports issued by panels in trade disputes brought by WTO Members. Appellate Body Reports, once adopted by the WTO’s Dispute Settlement Body, automatically become authoritative decisions that must be accepted by the parties to the dispute. The Appellate Body is composed of seven persons who serve for four-year terms and, as per the DSU’s rules, a division of three panelists is required to hear each appeal. Owing to the Trump Administration’s formal objection to aspects of the AB’s functioning (dating to Spring 2017) and its exercise of a veto on appointing new panelists (dating to September 2018), the AB will lack the requisite three-person quorum to hear cases from 11 December 2019 onwards. This will, in effect, debilitate the functioning of the WTO’s dispute settlement system.

The WTO and its dispute settlement body (DSB) is unique on a number of counts. It is the rare instance of an enforceable, rules-bound multilateral institution created following the end of the Cold War. It is the only multilateral institution that hosts a formal judicial body possessing compulsory jurisdiction sans opt-outs over its membership. Its two-tier appellate system is exceptional among international judicial bodies, including courts such as UNCLOS-constituted ones which rule on weightier disputes that touch on attributes of sovereignty. And the legislative facility of “authoritative interpretation” that its General Council (comprising all WTO members) is vested with to iron-out judicial ambiguities in the WTO legal texts, is without parallel.

The U.S.’ Appellate Body-related grievance is one facet – albeit the most prominent one, of a larger list of grievances leveled by Washington against the WTO. The list ranges from the inability of WTO rules to discipline the global market distorting effects of China’s state-run policies and practices to the tardy pace of WTO Member States’ fulfilment of their transparency and notification requirements to the alleged abuse of special and differential treatment-related self-designation rights by a number of wealthy and advanced developing countries.

To be clear, the World Trade Organization (WTO) as an institution, and the multilateral trading order as a systemic order, is not broken. With cooperation and goodwill on all sides, the international trading system with the WTO at its core can continue to make forward progress and achieve progressive liberalization of goods, services and investments.

The WTO as an institution is nevertheless reaching a breaking point because of the actions and pressure brought upon the institution by one dissatisfied Member State, the United States. Because the U.S. is, however, a key architect of the international trading system as well as one of its biggest players, the basis of its discontent and its proposed reforms need to be treated with appropriate seriousness. At the end of the day, therefore, ‘reform of the WTO’ essentially boils down to addressing the U.S.’ reform-related demands of the WTO.

The previous point should not be read as diminishing from the fact that there are serious shortcomings within the WTO-centered multilateral trading system. Some of the U.S.’ grievances are shared across the broader WTO membership and particularly by other key advanced country members, the European Union (EU) and Japan notably. The U.S.’ coercive – bordering on extortive – methods, however, most notably its attempt to block and de facto shut down the WTO dispute settlement system’s Appellate Body procedure, and thereby potentially sink the dispute settlement arm into disuse, is shared by none.

The origins of the U.S.’ reform related demands derive from the philosophical underpinnings of the Trump Administration’s ‘America First’ nostrums. This philosophical basis was most clearly laid out by President Donald Trump at the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) CEO Summit in Da Nang, Vietnam in November 2017. The APEC meeting was Trump’s first appearance at Asia’s region-wide multilateral summitry – hence the timing and venue of delivery of these remarks.

Two elements are key: first, that America will henceforth engage with foreign trade partners and foreign trade liberalization strictly on the basis of bilateralism (hence the U.S.’ exit from the Trans Pacific Partnership [TPP] agreement); and second, that America will not in principle submit itself to third party arbitral or enforcement mechanisms (essentially enforcement mechanisms that it cannot dictate bilaterally). Both these elements were captured in the space of one short but critically important paragraph during Trump’s Da Nang address. In his own words:

"I will make bilateral trade agreements with any Indo-Pacific nation that wants to be our partner and that will abide by the principles of fair and reciprocal trade. What we will no longer do is enter into large agreements that tie our hands, surrender our sovereignty, and make meaningful enforcement practically impossible."

In addition to these two elements, President Trump laid down his administration’s view with regard to the WTO in stark terms:

"Simply put, we have not been treated fairly by the World Trade Organization…. we adhered to WTO principles on protecting intellectual property and ensuring fair and equal market access. They engaged in product dumping, subsidized goods, currency manipulation, and predatory industrial policies. They ignored the rules to gain advantage over those who followed the rules, causing enormous distortions in commerce and threatening the foundations of international trade itself. From this day forward, we will compete on a fair and equal basis. We are not going to let the United States be taken advantage of anymore."

The ‘they’ in this instance relates primarily to China, (although it also peripherally includes other large developing countries, such as India, Indonesia and South Africa, etc). In Trump’s view, the U.S. had been generous in inviting and assisting China’s accession to the WTO. China, allegedly, paid back this generosity by engaging in unfair practices, distorting global commerce, and undermining the foundations of the international trading system. The rules of the WTO-centered system would therefore need to be re-written – by coercive means if need be – to ensure that China’s ‘unfair’ practices are reined-in so that the global trading order can once again be restored to its original purpose of ensuring fair and equal market access.

Each of these elements – strict bilateralism; disassociation from third-party enforcement; reining-in China’s unfair trading practices – feeds into and informs the U.S.’ approach to WTO reform and its submission and proposals in this regard.

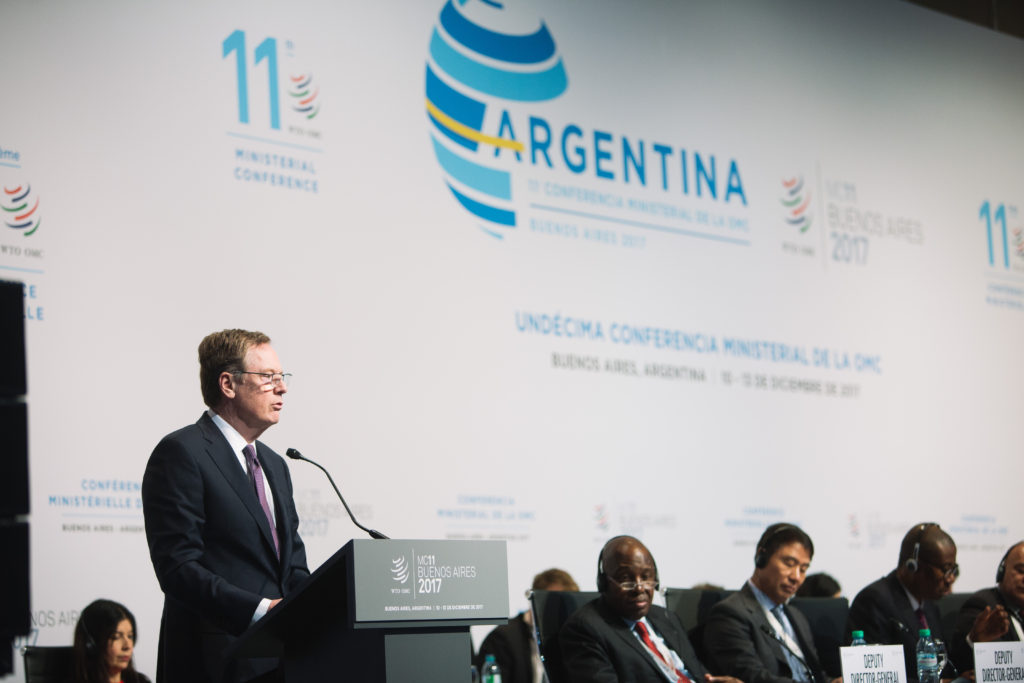

United States Trade Representative (USTR) Robert Lighthizer’s opening plenary statement at the WTO Ministerial Conference in Buenos Aires, Argentina in December 2017 as well as USTR’s more recent (February 2019) annual report to Congress on the state of China’s compliance with WTO rules provide the clearest expression of the U.S.’ WTO-related grievances. The statement, and report, also list out a number of primary challenges that the institution must contend with, going forward:

First, in the U.S.’ view, the WTO and the multilateral trading system is unequipped to deal with the challenge of coping with a large state-led economy in its midst, such as China. The WTOs rulebook needs to be overhauled to focus on the market distortions, notably chronic overcapacity and influence of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), thrown-up by the physical presence of such a large economy that broadly operates, in the U.S.’ view, on a non-market basis within the global trading system. In this regard, given that the current WTO rules are inadequate and the prospect of crafting new ones is likely to be time-consuming, ‘like-minded’ WTO members should coalesce together and implement effective strategies to counter the unique distortions posed by China’s global trade and investment footprint.

Second, much like the WTO’s inadequate current rulebook to discipline China, the WTO’s dispute settlement system is unsuited and ill-designed to adjudicate on many of China’s market distorting policies and practices. The dispute settlement system, in the U.S.’ view, is designed to address good faith disputes where one Member State suspects that another Member State has breached its obligations. In the U.S.’ view, the mechanism is not designed to and is incapable of dealing with complaints against a Member State (China) who’s trade regime and practices conflict with the fundamental underpinnings of the WTO system itself. Over-and-above this China-specific shortcoming, it is also the U.S.’ view that the Appellate Body (AB) of the WTO’s dispute settlement system has for quite some time now exceeded its legal authority and strayed from the role and mandate that Member States had assigned it at the time of the WTOs founding in the mid-1990s. This overreach by the AB has gravely diminished the U.S.’ sovereignty.

Third, even as it is difficult to negotiate new rules within the WTO – given the breadth of the WTOs membership and therefore the weak consensus for reform – the existing rules, the U.S. argues, are not being honored sincerely or in full. A key case in point is the WTOs rules on transparency and notification. These transparency and notification rules are fundamental to the WTO’s ability to monitor whether Member States are implementing their WTO commitments properly. A number of large, developing counties (including China and India) are, however, slow to file their obligatory notifications, and some of the filed notifications themselves are incomplete. This makes it difficult to monitor if these countries’ policies and practices abide by the WTOs rules.

Fourth, akin to the case of abuse of the WTO’s transparency and notification rules, another instance of abuse of rules concerns the ‘developing country’ status – and thereby the privileges of ‘special and differential treatment’ – that most Member States within the WTO self-declare and claim. As countries grow richer, they are obliged to graduate out of ‘developing country’ status. Very few do so however, including a number of’ advanced developing counties’ as well as some obviously rich countries (such as Kuwait, Singapore, Qatar, etc.). They continue to self-declare as ‘developing countries’ in order to enjoy the flexibilities accorded in terms of taking on softer binding commitments. As a result, the current distinction between developed and developing countries no longer reflects the reality of the rapid economic growth in certain developing countries – China foremost. And this lack of differentiation has, in turn, impeded the negotiating function of the WTO and, unaltered, could potentially cast the institution into irrelevance.

Overall, most – if not all – of the four grievances have a clear China-specific angle. China is either engaging in unfair trade practices that go against the purposes of the multilateral trading system, or, alternatively, the system with the WTO at its core is incapable of reining-in China’s policies and practices. China is also abusing its rights and privileges within the institutional set-up of the WTO, both by claiming developing country status and by being tardy in its transparency and notification obligations. And over-and-above this, the dispute settlement system too is both incapable of bringing China to book while at the same time it has overreached and abused its authority and abridged American sovereignty.

Over the course of multiple Dispute Settlement Body (DSB) meetings at the WTO in Geneva in 2018, the Trump Administration laid out its fundamental grievances with precision regarding the dispute settlement system and the malfunction of the Appellate Body (AB), in particular. The essence of its AB-related grievances is that the body has strayed from its WTO-mandated remit, overreached its authority and, in the process, diminished American sovereignty.

The specific Appellate Body-related grievances advanced by the Trump Administration are: the AB tends to issue advisory opinions on matters that are extraneous to resolving the relevant dispute at hand; the AB extends its review of facts to cover the meaning and interpretation of domestic law; AB case reports should not be treated as precedents during future cases, as the AB tends to do; the AB often-times fails to meet its allotted 90-day period to conclude proceedings; and AB members continue to serve on appellate panels (to complete pending appeals, it should be noted) even after the expiry of their terms. See table below for a brief description of each individual grievance and the formal response by the European Union (E.U.) to each grievance.

There is wide support across the WTO membership for the U.S.’ grievances. Numerous national delegations have spoken out in favor. In late-November 2018, a compellingly diverse group of developed and developing countries, including the EU, China, India, Canada, Norway, Australia, Korea and Mexico, jointly submitted a constructive proposal that substantially redresses the disquiet surrounding the AB’s judicial overreach and the U.S.’ grievances.

On the other hand, the depth of the support across the WTO membership is shallow, given that the extent of the AB’s overreach has been modest, at best. And no national delegation at the WTO supports the Trump Administration’s methods, especially its unilateral veto over AB appointments which is jeopardizing the very future of the WTO’s dispute settlement function. Indeed, the unwillingness of the Trump Administration to admit ‘yes’ for an answer to the constructive proposals that have been forwarded by the membership has tended to confirm the view that the U.S.’ grievances and criticisms are more ideological than truly solutions-oriented.

It bears noting in this context that U.S. ‘sunset industries’, steel notably, has been a consistent ‘loser’ in successive trade remedies cases that have been heard before Appellate Body panels. It is not coincidental either that the steel industries’ foremost resident ‘Beltway’ champion in trade remedies cases through the 1990s and 2000s was then-private lawyer and currently USTR, Robert Lighthizer. In the 22 years between the January 1995 commencement of the WTO and his nomination to USTR’s leadership position in May 2017, the U.S.’ sunset industries were hauled to the WTO court as a respondent in 57 percent of WTO trade remedies disputes – fully five times as many as the next most frequent respondent, the E.U. In 90 percent of cases, the U.S. came away holding the short end of the stick. On critical occasions, further, it was the Appellate Body which, in Lighthizer’s view, had overreached in the course of overturning initial panel decisions that had favored the U.S. Lighthizer, today, has an axe to grind at the WTO’s Dispute Settlement Body (DSB).

At this time, 117 WTO members have issued a call to launch a concerted process for filing vacancies on the Appellate Body, marking two years since proponents first issued their joint appeal in Geneva. Whether USTR Lighthizer is listening – or even cares to listen – to their appeal is a separate matter though.

The U.S. argues that the WTO requires new rules to discipline the mercantilist practices of state-led or state-linked economic actors, such as China, in the international trading system. WTO rules, as they stand, are not equipped to deal with the chronic distortions, industrial subsidies and influence of China’s state-owned enterprises. Because devising new rules within the WTO’s framework is likely to be a long-drawn-out affair however, the U.S. has been working within a narrower trilateral format (US, EU, Japan) to brainstorm and craft new model rules in this regard. So far, six rounds of discussions dating back to March 2018 have been conducted. The most recent round was conducted in Paris on 23 May 2019. Presumably, once the new rules have been crafted within the trilateral set-up, they will then be ‘pluralized’ within a ‘like-minded’ group of WTO member states that will form the core nucleus of countries that advocate and defend these rules – and the market access privileges tied to these rules – against outsiders, foremost China.

The U.S.-E.U.-Japan consultations are structured along three work-streams. The first work-stream pertains to Confronting Non-Market-Oriented Policies and Practices. Within this work-stream, the goal is to identify elements or criteria that signal that market conditions exist for businesses and industry within an economy. The absence of these criteria would, in effect, signal that the relevant economy is not operating under market-oriented conditions and would thereby be excluded from the benefits conferred upon the other market-oriented economies.

The second work-stream relates to Strengthening Rules on Industrial Subsidies and State-owned enterprises (SOEs). The aim of this work-stream is to develop effective rules to address the market-distorting behavior of state enterprises and confront particularly harmful subsidy practices such as: state-owned bank lending incompatible with a company’s creditworthiness, including due to implicit government guarantees; government or government-controlled investment fund equity investment on non-commercial terms; non-commercial debt-to-equity swaps; preferential input pricing, including dual pricing; subsidies to an ailing enterprise without a credible restructuring plan; and subsidies leading to or maintaining overcapacity.

In May 2018, the trilateral working group released a ‘scoping paper’ that outlined first principles to define the basis for the development of more stringent rules on industrial subsidies. The objectives of the discussions listed in the scoping paper were:

The three partners agree that a number of other WTO Members do not notify at all or fail to notify most of the subsidies granted or maintained within their territories. This prevents other WTO Members from evaluating the trade effects and understanding the operation of notified subsidy programmes. The partners therefore agree to construct direct or indirect incentives for WTO Members to fully comply with their notification obligations.

There is a general convergence among the three partners on the need to better address market-distorting behavior of public bodies and SOEs. Such entities are the backbone and the distinctive feature of certain state-driven economic systems, through which the state decisively governs and influences the economy.

The three partners therefore agree to discuss the basis for determining that an entity should be characterized as a “public body;” how to address state-influenced market-distorting behavior of entities not characterized as public bodies; and additional obligations and rules for public bodies and SOEs, including increased transparency.

The three partners as a start agree that the most harmful types of subsidies should either be prohibited outright, or the subsidizing country be obligated to prove that the subsidy does not cause commercial harm to others.

– to develop new rules that provide a targeted remedy to address subsidies related to excess capacity.

– to find ways to strengthen the provisions of the WTO rules to allow for greater information gathering in relation to subsidies and their effects.

The final work-stream relates to Cooperation and Enforcement of Stronger Rules against Forced Technology Transfer Policies and Practices. The goal of this work-stream is to build on existing WTO rules and develop far stronger rules and enforcement mechanisms to address domestic regulatory shortcomings and abuses, such as administrative review and licensing processes based on unclear rules; regulatory processes allowing for wide and unfair discretion (e.g. marketing approvals); as well as non-conforming licensing restrictions (where foreign investors are limited in setting market-based terms when negotiating their technology licensing agreements).

On 29 July 2019, Donald Trump issued a White House Memo directing his USTR to “use all available means to secure changes at the WTO that would prevent self-declared developing countries from availing themselves of flexibilities in WTO rules and negotiations that are not justified by appropriate economic and other indicators.” Should substantial progress not be made, remedial action including “ending unfair trade benefits” is proposed. The White House’s dissatisfaction on self-designation, which allows developing countries to enjoy special and differential treatment (S&DT) in the course of embracing and implementing WTO legal commitments, stems from the abuse of this privilege by many rich and relatively-rich countries. 7 out of the 10 wealthiest economies in the world as measured by GDP per capita (on a PPP basis) – Brunei, Hong Kong, Kuwait, Macao, Qatar, Singapore, and the United Arab Emirates – currently claim developing-country status. Two OECD countries – Mexico and Turkey – too claim this status. The main intent of this naming-and-shaming exercise however is to force China to graduate out of ‘developing’ to ‘developed’ country status.

Earlier in February 2019, the U.S. delegation at the WTO listed four criteria that should govern the classification of who is – and who is not – a ‘developed country’. Henceforth, any country that is (a) classified as “high income” by the World Bank; (b) is an OECD member state or in queue to accede to the OECD; (c) is a G20 member state; or (d) accounts for 0.5 per cent or more of global merchandise trade would be automatically deemed as a ‘developed country’ for WTO negotiation purposes. The criteria constitute a wide net, to say the least.

The U.S. proposal has met concerted pushback from a range of ‘developing country’ delegations at the WTO, including Bolivia, India, Oman, Pakistan, Venezuela and, crucially, China. Their claim is that S&DT is an unconditional and treaty-embedded right and stripping that unilaterally would “erode the foundation” of the rules-based trading system. A thoughtful middle path on this development dimension issue has been laid out by Norway, New Zeeland, Singapore and Switzerland. Their view is that while the principle of self-designation and S&DT is firmly embedded in text, there should be no one single pre-defined operational modality that is horizontally applied across every trade subject under negotiation. Rather, S&DT should be exercised in relation to specific and concrete subjects – and objectives – in the context of trade negotiations.

It bears noting in this overall context that the World Bank maintains a useful hybrid classification system that divides countries into four groups: low income, lower middle income, upper middle income, and high income. For the current 2019 fiscal year, low-income economies are defined as those with a GNI per capita of $995 or less in 2017; lower middle-income economies are those with a GNI per capita between $996 and $3,895; upper middle-income economies are those with a GNI per capita between $3,896 and $12,055; and high-income economies are those with a GNI per capita of $12,056 or more. China is closing-in but still below the World Bank’s high-income economy threshold.

A fundamental task of the WTO is to monitor whether Member States implement the WTO agreements properly and whether they make their trade policies transparent by following WTO notification rules. This monitoring is done in the regular WTO councils and committees as well as the Trade Policy Review Body. While many WTO members invest significant resources to make complete and timely notifications, there are equally many other members, typically developing countries, that do not comply sufficiently with their notification obligations. As a result, their trade practices remain opaque, which handicaps firms of complying Member States to access information and compete with domestic firms on an equal footing.

To remedy this shortcoming, the Trump Administration in conjunction with a number of (mostly) developed country partners, including the EU and Japan, released a formal proposal in November 2018. The three key elements of the proposal are: (a) name and shame Member States that fall behind in their notification requirements; (b) encourage member states to provide counter-notifications to challenge the incorrect or incomplete notifications put out by a Member State; and (c) impose a graduated set of sanctions on countries that serially fall behind on their notification obligations. In extremis, this would involve officially designating the Member State as a “Member with Notification Delay” and the member would be treated as such within the WTO’s formal set-up. The pushback from some developing countries has deservedly been low key, citing for the most part capacity constraints.

It does bear pointing out in regard to this transparency and notification failing though that the largest respondent in the instance of WTO Article 22.6 cases is the U.S. The main purpose of an Article 22.6 case is to determine the upper limit – or the amount of bilateral trade – over which a complainant country is authorized to impose retaliatory import tariffs in the event that the respondent does not comply with an earlier WTO dispute settlement decision. Simply said, the U.S. is the leader – or rather laggard – within the WTO system in complying with its dispute settlement obligations (there have been no cases of countermeasures pursuant to Article 22.6 sought against China for non-compliance with WTO recommendations). While complying with transparency and notification obligations is essential, it cannot be the case that complying with adverse dispute settlement awards (which follow a chain of actions after the notifications process) is any less essential. To the contrary, it is much more so, and the penalties proposed by advanced countries for failure to live up to notification rules should apply even more forcefully in the instance of Article 22.6 non-compliance.

The WTO-centered trading order is approaching a critical fork in the road. The impairment of its dispute settlement function is a damaging blow that will rock the organization back on its heels. The EU’s attempts to devise a constructive workaround to the current system has been unsuccessful so far. Beyond dispute settlement and beyond ‘America First’ trade policy and politics, there is a pressing need to update the WTO’s rulebook so as to bring commercial developments related to cross-border data flows and trade-distorting industrial subsidies within the fold. Particularly with regard to the latter, the negative externalities radiating internationally from China’s state-owned enterprise (SOE) policies and practices need to be matched by equivalent disciplines that capture their global market-distorting behavior. It goes without saying though that no effort at significantly pruning and altering the nature of China’s industrial policy interventions will bear fruit if the advanced countries’ sky-high, trade distorting agricultural subsidies is seen to be off-limits to similarly aggressive reduction disciplines.

For its part, China would be well-served to firmly inscribe a number of reform principles within its trade, investment, industrial and intellectual property rights (IPR) policies and practices. Its China’s industrial policy interventions must metamorphose from a subsidies-based model to a fiscal incentives-based and indicative planning model. This will require the reformulation of the role of the state as a producer as well as subsidizer at every level of government. Its innovation policies, too, must be framed on a technology-neutral basis and its matrix of support measures should evolve towards government sponsorship of basic research and the licensing of government-sponsored IPR.

Above all, at the end of the day, both the U.S. and China and its key multilateral partners need to philosophically and politically commit to regulating their preferences and resolving their differences within the four corners of a rules-bound multilateral trade and investment framework.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2025 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Closing the Climate Financing Gap: New Proposals and Emerging Risks