Image Source: UnSplash

Resident Senior Fellow

The lessons learned from the response to the “Spanish” flu of 1918 are just as relevant today in this age of COVID-19 – early implementation of multiple cautionary interventions, such as closing schools, churches and theaters (“social distancing” measures) and strict quarantining of infected locations (isolation measures) are directly correlated with lower peak death rates.

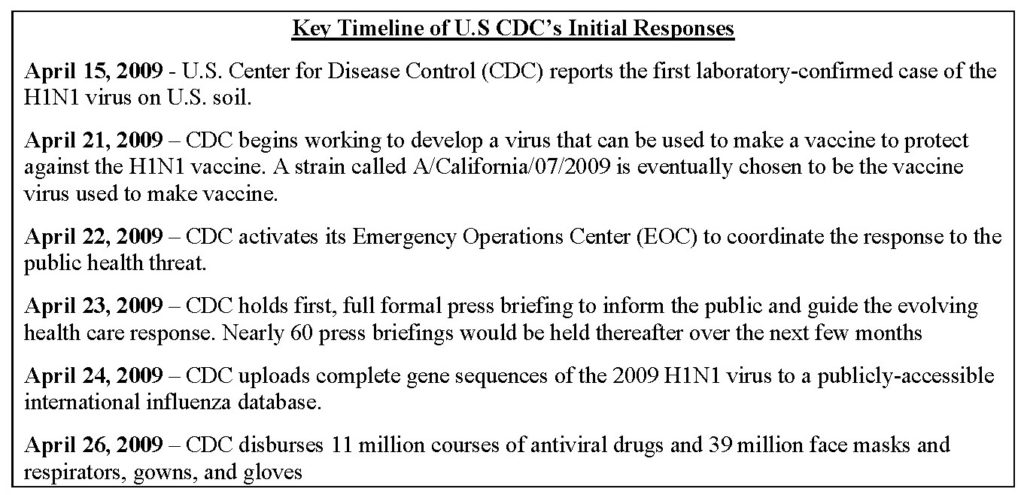

During the H1N1 (swine flu) virus of 2009, both, the U.S. Center for Disease Control (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) had mounted a creditable and capable early response. There was timely detection, identification, initial characterization and monitoring of the virus, and CDC released 11 million courses of antiviral drugs and 39 million face masks and respirators, gowns, and gloves within 10 days of the first laboratory-confirmed case of H1N1 in the U.S.

That said, there were important shortcomings too. The Obama Administration’s Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) vastly overestimated its influenza vaccine manufacturing surge capacity and, due to its failure to follow through, dented its credibility and trust in the public’s eye. For its part, the WHO failed to articulate a consistent, measurable and understandable depiction of the severity of the H1N1 pandemic, conflating the geographic spread of the virus with severity – in turn, accentuating public confusion.

The Trump Administration’s response to the spread of COVID-19 has not exactly been a profile in competence. After downplaying the depth of severity of transmission for weeks-on-end, the White House, in a remarkable turnaround, declared a “national emergency” on Friday, March 13, 2020. The U.S. Center for Disease Control (CDC) has not covered itself in glory either. Although it has put out COVID-19 related notice announcements from as early as January 6, its testing and diagnostic response has been abysmal. It is of the essence, at this time, that diagnostic testing be ramped up rapidly.

Bearing in mind the lessons from pandemics past, it is essential to implement early “social distancing” measures and isolation measures. Public communications must be transparent and trust-worthy, striking a fine balance between the fulfilling the public’s right to know and maintaining general calm. A consistent, measurable and understandable depiction of the spread as well as severity of the virus must be made available, including putting to use information and communication technologies wisely via a real-time notification system. Finally, truth and transparency on the state of vaccine development is paramount. In all of this, an all-of-government role is not just important – it is indispensable.

The “Spanish” flu of 1918 is considered to be one of the most lethal pandemics in human history. The flu did not originate in Spain; the country is wrongly associated with it. Nevertheless, over the course of 15 months starting in early-1918, the flu infected a third of the world’s population, killed almost 50 million people, and compounded the devastation to the global economy that the Great War had already wreaked. In the United States, the flu killed 675,000 Americans (by contrast, 53,000 U.S. lives were lost in World War I combat operations) and stunted average U.S. life expectancy by more than ten years. Like COVID-19 today, the “Spanish” flu was an unknown strain of influenza at the time and for which no vaccine or established treatment regime existed. It too spread through respiratory droplets with the majority of those succumbing to the pandemic dying via secondary bacterial pneumonia.

As devastating as the “Spanish” flu was, the pandemic also left future American and international public health professionals with important lessons learned – the foremost of which was that U.S. cities that had implemented multiple cautionary interventions at the early phase of the outbreak were also the ones to witness peak death rates that were almost 50% lower than the case of comparable cities that had been less vigilant in their initial response. Early implementation of certain interventions, such as closing schools, churches and theaters (“social distancing” measures) and strict quarantining of infected locations (isolation measures), were directly correlated with lower peak death rates.

The lessons learned from that deadly pandemic provide a useful context to understand the measures that have been rolled out and are being implemented by the Trump Administration, as it girds its loins to combat the presence of COVID-19 on U.S. soil. The lessons learned also provide useful context to understand the U.S. and the World Health Organization’s (WHO) historical responses to past influenza-related outbreaks over the previous decade-and-a-half. This Primer highlights one such historical response in particular – that being the H1N1 influenza outbreak in 2009, which was the only major pandemic involving the U.S. over the past decade. Following the analysis of the U.S. and international responses and lessons learned from this H1N1 pandemic, the Trump Administration’s (unfortunate) less-than-vigilant approach to implementing a number of early cautionary interventions to contain the COVID-19 virus will be briefly summarized.

Over the past decade, there have been a number of major global epidemic threats. These include the: H1N1 (swine flu) virus, MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome), the Ebola virus and the Zika virus. Of the four, the H1N1 influenza was the only one to significantly impact the U.S. The U.S. Center for Disease Control (CDC) has estimated that there were 60.8 million cases, 274,304 hospitalizations, and 12,469 deaths in the U.S. due to the H1N1 influenza from April 2009 to April 2010.

MERS had represented a very low risk to the general public in the U.S. Only two patients in the U.S. ever tested positive for MERS-CoV infection – both in May 2014. Both cases were among healthcare providers who had lived and worked in Saudi Arabia. Both traveled to the U.S. from Saudi Arabia, where scientists believe they were infected. Both were hospitalized in the U.S. and later discharged after fully recovering.

Overall, only eleven people were treated for Ebola in the U.S. during the 2014-2016 epidemic period. In September 2014, the U.S. CDC confirmed the first travel-associated case concerning a man who traveled from West Africa to Dallas, Texas. The patient died subsequently in October 2014. Over the next few months, a number of other people were exposed to the virus, most becoming ill while in West Africa. The majority of these individuals were medical workers, with one succumbing to the illness.

Prior to 2014, very few travel-associated cases of Zika virus disease were identified in the U.S. In 2015 and 2016, large outbreaks of the Zika virus occurred in the Americas, resulting in an increase in travel-associated cases in U.S. states, widespread transmission in Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands, and limited local transmission in Florida and Texas. By 2017, the number of reported Zika virus disease cases in the U.S. had started to decline. Altogether, in 2016, the most lethal year, there were a total of 5,168 cases – 95% of them being travel associated. There was one solitary Zika virus-related death in the continental U.S. altogether.

The first case of the H1N1 virus was detected in California in late-March 2009 and was laboratory-confirmed on April 15, 2009. By end-April 2009, cases had been reported in a number of U.S. states as well as internationally, leading the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC). By June 2009, the rapid spread of the infection to 73 countries and more than 26,000 laboratory-confirmed cases, led to its elevation by the WHO as a full-fledged pandemic.

In the U.S., the H1N1 pandemic occurred in two waves. The first wave occurred during spring 2009 and the second wave during fall 2009, with H1N1 influenza activity peaking in October 2009. When the H1N1 influenza outbreak occurred in April 2009, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) began working to isolate the H1N1 influenza strain and worked with five vaccine manufacturers to develop a H1N1 vaccine to protect the public against the virus. But notably, unlike the seasonal influenza vaccine, which is largely purchased by the private sector, the federal government purchased all of the H1N1 vaccine licensed for use in the U.S. HHS thereafter took the lead in allocating doses of the vaccine to each state for distribution based on the overall population of the state. The states, in turn, placed orders for their allocated doses and determined which providers were to receive the vaccine.

In addition to the production and distribution of the H1N1 vaccine, another important U.S. federal government action in response to the H1N1 pandemic was the activation and deployment of influenza response supplies from the Strategic National Stockpile (SNS).The SNS, at the time managed by the U.S. CDC (and now operationally headed by the HHS Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response – ASPR), contains large quantities of medicine and medical supplies intended to protect and treat the public if there is a public health emergency that is severe enough that local supplies may be exhausted. The H1N1 pandemic marked the largest deployment of materials from the SNS in an emergency situation in the U.S.

Overall, one of the key lessons coming out of the U.S. Government’s response was that planning and preparedness are key and that good planning and preparedness have a high payoff during such a critical health emergency. As the U.S. Government Accountability office (GAO) observed subsequently, many funding and planning activities – including funding for vaccine production capacity, planning exercises, and interagency meetings prior to the H1N1 pandemic – positioned the Obama Administration to respond reasonably effectively. And the inter-agency working group, convened by the National Health Security Strategy, too, fostered relationships that proved advantageous during the response.

As noted earlier, the first case of the H1N1 (or swine flu) virus in the continental United States was detected in California in late-March 2009 and was laboratory-confirmed on April 15, 2009. By February and March 2009, however, laboratory-confirmed cases of the H1N1 virus had already appeared in Mexico and had alarmed public health specialists – given the exceptionally high criticality rate of early patients. By end-April, cases were reported in countries on various continents, including Canada, Spain, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Israel, and Germany. On April 25, invoking its authority under the 2005 International Health Regulations (IHR), the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC). A dedicated internal group to coordinate the response to the widening outbreaks was thereafter established by the WHO. With a total of 73 countries reporting more than 26,000 laboratory-confirmed cases, the WHO raised the H1N1 virus outbreak to be a full-fledged “pandemic” on June 11, 2009.

The H1N1 virus also prompted the first instance of activation of the provisions of the WHO’s 2005 International Health Regulations (IHR), which had gone into effect in 2007. The IHR outline the responsibilities of individual countries as well as the WHO’s leadership role during the course of managing a public health emergency of international concern. The Regulations themselves were shaped by the response-related experience, and lessons learned, during the SARS outbreak of 2003. In January 2010, the WHO commissioned an international review of the H1N1 pandemic’s outbreak, with special attention paid to the performance of the WHO and the functioning of the 2005 International Health Regulations – the first time these Regulations had been tested in real-world circumstances. Some of the key successes, shortcomings and lessons learned in the course of the WHO-led global response, as enumerated by the chairman of the review panel, Dr. Harvey Fineberg, are listed below.

The WHO achieved a number of notable successes during the early stages of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. These included:

Balanced against these accomplishments were a number of systemic difficulties observed as well as missteps committed by the WHO in the course of combatting the virus. These included:

The Trump Administration’s response to the spread of COVID-19 has not exactly been a profile in competence. After downplaying the depth of severity of transmission for weeks-on-end, the White House, in a remarkable turnaround, declared a “national emergency” (under the Stafford Act) on Friday March 13, 2020. There have been only two infectious disease-related emergency declarations in the past – both, targeted ones in 2000 when the Clinton Administration declared emergencies in New York and New Jersey in response to the West Nile Virus. A federal public health emergency (PHE) declaration has been in effect though since January 31, 2020.

The U.S. Center for Disease Control (CDC) has not covered itself in glory either. Although it has put out COVID-19 related notice announcements from as early as January 6, its testing and diagnostic response has been abysmal. While South Korea had conducted 220,000 tests as of March 12, the CDC had yet to reach the 5,000 mark as of that date – in turn, more-or-less ensuring that the U.S. domestic response to combatting the outbreak is many weeks behind where it should be at this given point of time. The slow rollout of testing kits has been compounded by the inflated – and misleading – accounting of the number of tests pushed out by senior members of the Administration. It is of the essence, at this time, that diagnostic testing be rapidly ramped up.

Be that as it may, the lessons of past pandemics should also be borne in mind. Early implementation of “social distancing” measures and isolation measures are imperative. Public communications must be transparent and trust-worthy, striking a fine balance between the fulfilling the public’s right to know and maintaining general calm. A consistent, measurable and understandable depiction of the spread as well as severity of the virus must be made available. In this regard, information and communication technologies should be put to wise use, so that a real-time notification system about newly infected patients, maps on the spread of the virus, facility closures, etc. can be promptly transmitted to the public and allay undue anxieties.

Transparency on the state of vaccine development is equally important. False promises in this regard are highly damaging. And when such vaccine is finally available, the manifold logistics challenges to storage and distribution must be sorted out expeditiously. In all of this, the role of government is not just important – it is indispensable. It must assume a standout all-of government – and, if need be, inspire an all-of-society – response to combating and containing the spread COVID-19. And, if necessary, it should not hesitate to take recourse to coercive measures (to enforce quarantines) and mow down any legislative, legal, private sector or societal obstacles that might potentially stand in the way of an expeditious and concerted response.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2024 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

The Shanghai Communique’s relevance endures in an age of US–China strategic competition