- Blog Post

- Jessica L. Martin

Photo Credit: CDC

Research Associate & Program Officer

Research Assistant

Research Assistant

As the novel coronavirus, officially named COVID-19 by the World Health Organization (WHO), has spread globally, both the coverage and response from western countries have evolved. Researchers from the Institute for China-America Studies (ICAS) have developed a living database in order to track developments in the coverage and response by Western actors, both government and private, with a focus on perspectives from within the United States.

The following is a summary of the initial findings from the database, which will continue to be developed as the response to the epidemic progresses. ICAS will continue tracking major responses to COVID-19 and publish more in-depth analysis as the issue evolves. The database itself will be available for use by the public shortly after the release of this publication.

Disclaimer: This database does not attempt to be an exhaustive list of all COVID-19 coverage and responses, rather it intends to identify trends and provide a chronological summary of the Western narrative and response to the disease.

This study was conducted through research of over 190 Western public and private sector responses, typically beginning with online media sources, to the coronavirus outbreak from December 1, 2019 to present. Search terms used include combinations of ‘(novel) coronavirus,’ ‘pneumonia,’ ‘COVID-19,’ ‘SARS-CoV-2,’ ‘China,’ and ‘Wuhan’.

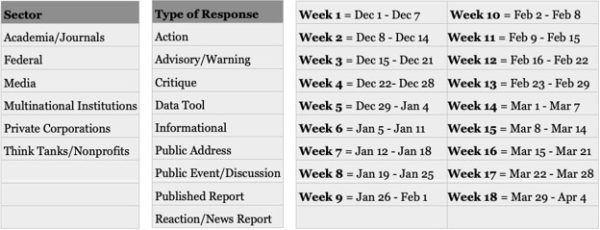

The data was organized in a customizable spreadsheet according to Sector, Publication Date, and Type of Response. The week-by-week count into the outbreak was also determined and applied to each data point (based on a Sunday to Saturday schedule), beginning with December 1. This date was selected as the beginning of Week 1 because, as reported by the Wall Street Journal, The Lancet published a study that indicated a patient had shown symptoms of COVID-19 on December 1. This patient is considered to be the first reported case.

The sectors and related types of responses in the database are outlined below:

Even before the coronavirus outbreak became common public knowledge in mid-January 2020, Western media and health professionals were on heightened alert towards infectious diseases due to an abnormally early and stronger onset of the flu season. Additionally, Chinese medical professionals reported that two children were diagnosed with the rare avian flu that they supposedly had contracted while visiting a poultry market in Anhui and Fujian. While this strain of avian flu is genetically unrelated to COVID-19, it indicates that multilateral institutions and other international medical professionals were fixated on China prior to COVID-19 being identified.

As the COVID-19 outbreak continued to spread and more became known about the virus, the terminology used to describe the outbreak concurrently evolved. The West first began discussing a “mysterious” “pneumonia-like illness” from China during Week 6 before reclassifying it the following week as the ‘novel pneumonia virus’ and ‘Wuhan pneumonia’ as its origins became more evident. By Week 8, the term ‘coronavirus outbreak’ became popular in the media and by Week 9, reports typically labeled the disease as the ‘novel coronavirus’ as its unique nature was further acknowledged. After the WHO formally named this disease “COVID-19” in Week 11, most professionals in academia and governments adopted ‘COVID-19’ as part of their communications. Western media and private corporations instead typically now refer to it as the ‘novel coronavirus (COVID-19)’ and some experts are now starting to toy with the term ‘pandemic,’ suggesting that they believe COVID-19 to be a wide-spread problem.

In Week 9, immediately after the WHO and China’s Health Commission confirmed the possibility of human-to-human transmission, more than 100 Center for Disease Control (CDC) officials were stationed at three major U.S. international airports— to be followed later at more than 20 airports—to conduct screenings on passengers coming from Wuhan, China.

On January 29, U.S. President Donald J. Trump announced the formation of the President’s Coronavirus Task Force. He stated that the Task Force would be in charge of monitoring the spread of the virus as well as leading the U.S. government’s response to the viral outbreak. On January 30th, the World Health Organization’s International Health Regulations Emergency committee declared the novel coronavirus of 2019 as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC). Although the WHO did not recommend travel restrictions, later that week, the U.S. State Department increased its travel advisory to the highest level – ‘4: Do Not Travel.’ During a press conference with members of the President’s Coronavirus Task Force, Alex Azar, Secretary of Health and Human Services, announced that the 2019 novel “coronavirus presents a public health emergency in the United States.” Furthermore, starting at 5pm, EST on February 2, the United States implemented a temporary travel ban on foreign nationals who are not an immediate family member of U.S. citizens and green card holders (permanent residents). Those who had traveled to China within the last 14 days would be denied entry to the United States. The White House and the Task Force reiterated that the risk of infection to Americans remained low. Simultaneously, a top official at the CDC, Principal Deputy Director Dr. Anne Schuchat cautioned that “this is the time to open up your pandemic plans and see that things are in order.”

Dr. Jennifer Huang Bouey, Associate Professor and behavioral epidemiologist at the Department of International Health, School of Nursing and Health Studies at Georgetown University, speaking at an event on the coronavirus outbreak, observed that government actions such as quarantine and travel bans are common tools for social distancing to help delay the spread of COVID-19 or other infectious diseases.

The impact of think tanks and nonprofits vary immensely depending on the size and purpose of the organization. For instance, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, an extremely well-funded and large organization, has pledged to deliver up to $100 million to improve detection, isolation and treatment efforts; protect at-risk populations in Africa and South Asia; and accelerate the development of vaccines, drugs, and diagnostics for coronavirus response. Think tanks have helped shape the narrative of COVID-19 by providing policy recommendations through expert analysis and creating public forums for discussion. Industry associations, like the U.S.-China Business Council, have helped to organize the private sector into providing relief efforts. Other nonprofits, such as Healthcare Ready, act as a bridge between the public health and emergency management sector and the private health care supply chain to promote information, resource sharing and expertise on how to provide assistance in impacted areas.

Initially, the COVID-19 epidemic was contained to China’s mainland and was the concern of the Wuhan Provincial Government. Once the disease was discovered outside the Chinese mainland in Week 7 and began impeding citizens’ daily lives, governments from around the world began to get tested on their various national pandemic strategies.

Health screenings at international airports and the increased potential for quarantine quickly became a standard around the world. In Week 7 of the outbreak, Thailand was the first country outside of China to report a COVID-19 case. Authorities quarantined the infected Chinese national, who eventually recovered and was released. India quickly set up screening wards and remote quarantines, soon joining France, Italy, and other nations in repatriating their citizens from Wuhan via chartered flights. As early as Week 8, experts were increasingly questioning the effectiveness of these screenings.

Many nations have followed suggestions and travel advisories set by the WHO while expressing the paramount importance of human health and safety. For example, South Korea’s Ministry of Education postponed the collegiate spring semester and placed Chinese exchange students under their protection. In Week 11, Canada’s Health Minister Patty Hajdu publicly stated that closing borders is “not effective.”

Other nations shuttered their borders—counter to the WHO’s suggestion—in order to ‘reverse-quarantine’ potential viral threats, in some cases leaving their citizens in China. For instance, Moscow closed its eastern border with China and decided to quarantine at-risk Russians coming from Wuhan in a Siberian forest bordered by members of the Russian National Guard. Australia followed Washington’s lead in banning arrivals from China, Iran recently banned border crossings by Iranians, and Pakistani students in Wuhan were outraged in mid-February, demanding that the Pakistani government evacuate them from Wuhan. North Korea still claims zero coronavirus cases, but experts remain skeptical.

Despite ongoing bilateral tensions, China’s neighbors, Japan and South Korea, have expressed tangible support for China in the form of medical equipment donations and buildings lit up in solidarity. The Vatican sent “tens of thousands” of face masks to China. In stark contrast, Washington has been chastised by Beijing for isolating itself and only caring about chartering American citizens out of Hubei Province. Washington did announce in early February though its readiness to assist China and other countries impacted by the virus to the tune of $100 million.

As the preeminent multinational authority on health and human safety, the United Nations’ World Health Organization has been driving the international dialogue on the COVID-19 outbreak. Multinational institutions have faced scrutiny in some cases; for instance, certain groups have accused the WHO of bowing to Chinese pressure. The European Union activated its Civil Protection Mechanism in Week 9 to repatriate EU citizens through two chartered flights based out of France. Two weeks after releasing its first Statement of Support in Week 9, the World Bank reported on the emergency assistance mechanisms that it offers. At the same time, the World Bank is also rushing to prevent fallout stemming from the pandemic-catastrophe bonds that it issued in 2017 and which have been triggered for the first time.

Private industry looked with uncertainty during the early weeks of the virus, but it was not until Weeks 9 and 10 that major actions were taken in the wake of the U.S. travel ban. Interruptions in supply chains are having a noticeable impact on major corporations and tourism. For instance, Foxconn Technology warned its employees not to go to its factory in Shenzhen, a coastal city in Southern China. Apple recently announced an earnings warning, indicating that it would not meet quarterly revenue expectations due to production interruptions because of the coronavirus. More recently, casino resorts in Macau like MGM and Wynn have temporarily ceased gaming operations at the request of the local government, and some cruise lines have canceled voyages to Asia through the third quarter of 2020.

Aside from these economic impacts, the private sector in the West has been playing an active role in the response to COVID-19. For instance, Twitter and Facebook announced that they will take steps to curtail the spread of false information. Pharmaceutical companies, such as Johnson & Johnson, are establishing public-private partnerships with the U.S. government to help develop a potential vaccine.

Within Weeks 8 and 9, the airline industry began to monitor the coronavirus situation as per airline procedures related to health concerns. U.S. airlines, including United, Delta and American, became some of the earliest airlines to cancel flights to and from cities in China, announcing temporary flight suspensions through the end of April 2020. Other international airlines followed their example and suspended flights to and from China. Many carriers announced that flight cancellations were also due to a lack of flight demand during this outbreak period. In order to provide flexibility for travel plans, airlines have waived flight change fees for impacted flights.

Academia has disseminated a variety of scientific research and resources for the public to gain a better understanding of the scope and seriousness of COVID-19. Of particular note is the Johns Hopkins Center for System Science and Engineering’s interactive map of the coronavirus, which tracks the global spread and impact of the disease using WHO and Chinese government data. In addition, academics have helped shape the conversation surrounding the disease and its impact via forums and discussions at universities, which have in turn helped keep the public well informed. Lastly, and most importantly, scientific researchers have published and shared internationally critical research that will help to treat the illness, such as the recently developed first 3D map of the virus.

Western media has found tracking cruise line activity to be particularly interesting. There have been multiple cases of COVID-19 appearing on cruise ships, and guests have been involuntarily quarantined (i.e. Princess Cruises in Japan, Costa Smeralda in Italy), and the quarantine methods used have been increasingly questioned by the media. In addition, the topics related to the virus that these media sources cover range from the purely informational, such as international efforts to develop a vaccine, to bandwagoning along with critiques of the Chinese government’s response to the illness, such as after the prominent death of Dr. Li Wenliang sparked additional backlash against the local government of Wuhan and the central government in Beijing. Not all coverage in Western media has been precise with its reporting; indeed there have been cases where notable outlets have reinforced the harmful Asian stereotypes that have been evoked and conspiracy theories spread.

Western media is also looking keenly at economic activity in China, with multiple index measurements attempting to provide an outlook on the short- and long-term economic impacts of the epidemic. For instance, the Wall Street Journal’s Daily Shot writes, “[w]hile part of the decline in the M1 money supply expansion was due to seasonal effects, we haven’t seen the year-over-year change in this metric hit zero in recent years.” Its economic impact is considered to be another critical indicator of how China has been handling the virus, with some corporations considering pulling investments out of China if fundamental economic indicators continue to deteriorate.

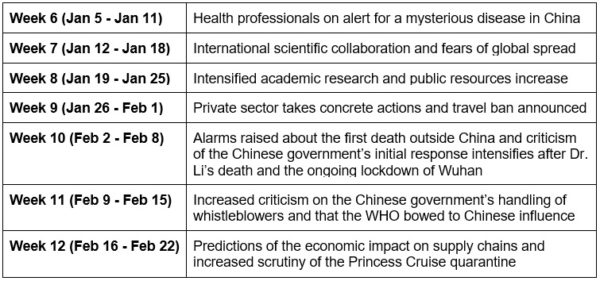

Although there is a great variance on the topics and actions on COVID-19 covered by Western media, governments, and other sectors, each week was found to have a relatively persistent theme. As there was very little coverage on the virus in December, largely due to a lack of understanding of its nature and spread, we characterize each week’s themes beginning with week 6.

According to Dr. Rebecca Katz, Professor and Director of the Center for Global Health Science and Security at Georgetown University, and other healthcare professionals who spoke at a public event at Georgetown University, there is still a tremendous amount we still do not know about COVID-19. This includes the length of the outbreak, how long it will take for an effective vaccine to be developed, the recovery rate, economic impacts, and more. With so many unknowns, incomplete or intentionally false information has led to the propagation of conspiracy theories, fraudulent remedies, and invocations of racial slurs and stereotypes in the media. Fortunately, though not without its own road bumps, efforts to combat this disease on a global scale have encouraged greater levels of scientific cooperation between China and other countries around the world, including the U.S.

ICAS will continue updating its COVID-19 coverage and response database and is currently in the development stage of a second database that focuses on Chinese coverage and responses, looking at similar sectors as a focus of study. As the terminology and issues related to the virus are constantly evolving, the methodology of the study may change as these developments necessitate. Therefore, the current database on Western coverage and response is not necessarily in its final form. Stay tuned for the upcoming release of the this database and other publications from ICAS related to the global COVID-19 response and public health measures.

The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening the understanding of U.S.-China relations through expert analysis and practical policy solutions.

1919 M St. NW Suite 310,

Washington, DC 20036

icas@chinaus-icas.org

(202) 968-0595

© 2025 INSTITUTE FOR CHINA-AMERICA STUDIES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.